2nd Canadian Infantry Division

Elements of the 2nd Division were selected as the main force for Operation Jubilee, a large-scale amphibious raid on the port of Dieppe in German-occupied France. On 19 August 1942, with air and naval gunfire support, the division’s 4th and 6th Infantry Brigades assaulted Dieppe’s beaches. The Germans were well prepared and, despite being reinforced, the Canadians sustained heavy losses and had to be evacuated, with fewer than half their number returning to the United Kingdom.

Following a period of reconstruction and retraining from 1942 to 1944, the division joined II Canadian Corps as part of the British Second Army for the Allied invasion of Normandy. The 2nd Division saw significant action from 20 July to 21 August in the battles for Caen and Falaise. Joining the newly activated headquarters of the First Canadian Army in the assault on northwestern Europe, the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division played a significant role in the retaking of the Channel Ports, the Battle of the Scheldt, and the liberation of the Netherlands. The division was deactivated shortly after the end of the war.

In early 1942, under Roberts, the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division participated in several additional full-scale combat exercises, again gauging the ability of Commonwealth divisions to repel a possible German invasion. As April and May progressed, the exercises intensified, becoming significantly more demanding on the participants. As a result, the 2nd Division was judged to be one of the four best divisions in the United Kingdom, and was selected as the primary force for the upcoming Allied attack on the German-occupied port of Dieppe, codenamed Operation Jubilee. Mounted as a test of whether or not such a landing was feasible, the Dieppe raid was to be undertaken by the 4th and 6th Brigades, with additional naval, air, and infantry support. Significant elements of the 5th Brigade were also involved.

On 19 August 1942, while British commando units attacked bunker positions on the outskirts of Dieppe, forces of the 2nd Division landed on four beaches. The easternmost, Blue Beach, which was situated at the foot of a sheer cliff, presented the most difficulties; the Royal Regiment of Canada, with a company of the Black Watch, was held at bay by two platoons of German defenders. Only six percent of the men that landed on Blue Beach returned to Britain.

The main beaches, codenamed White and Red, lay in front of Dieppe itself. Making only minor gains, the majority of the 4th and 6th Brigades became pinned down on the beach, and despite the arrival of an armoured squadron from the Calgary Tank Regiment, casualties were heavy. Reinforcements from the Mont Royals had little effect, and surviving forces were withdrawn by 11:00. Of the nearly 5,000 Canadian troops that participated, more than half were killed, wounded or captured.

At Green Beach to the west, part of the South Saskatchewan Regiment was landed on the wrong side of the Scie River, necessitating an assault over the machine gun swept bridge there so they could assault the cliffs on the west. The village of Pourville was captured but the eastern cliffs proved impossible to capture so blocking their assault on an artillery battery and a radar station. The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders were landed with the objective of moving south to attack an airfield and a divisional HQ. Neither battalion was able to achieve their objectives. As with the other three beaches, casualties among the Canadians were high with 160 fatalities.

In March 1944, training again intensified, heralding the coming invasion of Europe. On 9 March, the 2nd Division was inspected by King George VI, and by May the division numbered close to 18,000 fully equipped and trained soldiers. When D-Day arrived on 6 June 1944, the main Canadian assault was led by the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, while the 2nd Division was held in reserve. At this time, the division consisted of three brigades—4th, 5th and 6th, each of three infantry battalions, and a brigade ground defence platoon provided by Lorne Scots. In addition, at divisional level there was a machine gun battalion and a reconnaissance regiment provided by the Toronto Scottish Regiment (machine gun) and 8th Reconnaissance Regiment (14th Canadian Hussars), as well as various combat support and service support elements including field, anti-tank and anti-aircraft artillery, field engineers, electrical and mechanical engineers, and signals, medical, ordnance, service corps troops and provosts.

The attack on Juno Beach by the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division was the most successful of the five beaches attacked on D-Day, 6 June 1944. Having successfully landed in Normandy, Allied forces soon became embroiled in battles against German armour and were unable to significantly expand their beachhead; by the time the 2nd Division came ashore at the end of the first week of July, the entire front had congealed. Assigned to the II Canadian Corps, and subordinated to the British Second Army, the division assembled its brigades for combat while British and Canadian forces launched Operation Charnwood. It was a tactical success, but could not clear all Caen of its German defenders. Although originally a D-Day objective, Caen proved a difficult prize, holding out until 19 July when it finally fell to British troops during Operation Goodwood. In the aftermath, General Bernard Montgomery, commander of the Anglo-Canadian 21st Army Group, ordered elements of II Canadian Corps, commanded by Lieutenant-General Guy Simonds, to push forward towards Verrières Ridge, the dominant geographical feature between Caen and Falaise. By keeping up the pressure, Montgomery hoped to divert German attention away from the American sector to the west.

Operation Atlantic, launched on 18 July alongside Goodwood, had the objectives of securing the western bank of the Orne River and Verrières Ridge. The 2nd Division’s 5th and 6th Brigades were selected as the assaulting forces, with the 5th Brigade focusing on the Orne and the 6th on Verrières. The 4th Brigade were tasked with securing the flank of the operation, and the Royal Regiment of Canada attacked Louvigny on 18 July. Early on 19 July, the Calgary Highlanders seized Point 67, directly north of Verrières Ridge, and the following morning the Royal Highland Regiment of Canada crossed the Orne River and secured the flanks of the advance. In the afternoon, the 6th Brigade’s South Saskatchewan Regiment attacked the well-entrenched German positions on the ridge, with support from Typhoon fighter-bombers and tanks. However, the attack ran into torrential rain, and the Germans counterattacked in force. This and further German attacks inflicted heavy casualties on the South Saskatchewan Regiment and its supporting battalions, the Essex Scottish Regiment and the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada. On 21 July, the 5th Canadian Infantry Brigade reinforced Canadian positions on Point 67. In two days of fighting, the division suffered 1,349 casualties.

On 22 July 1944, Montgomery elected to use the Anglo-Canadian forces south of Caen in an all-out offensive aimed at breaking the German defensive cordon keeping his forces bottled up in Normandy. To meet Montgomery’s objectives, General Simonds was ordered to design a large breakout assault, codenamed Operation Spring. The attack was planned in three tightly timed phases of advance, pitting two Canadian and two British divisions against three German SS-Panzer divisions, which would be launched in conjunction with an American offensive, Operation Cobra, scheduled to take place on 25 July 1944.

The 4th Brigade attacked in the east with some success, taking Verrières village itself, but were repulsed at Tilly-la-Campagne by German counterattacks. The 5th Brigade, in the centre, made a bid for Fontenay-le-Marmion; of the 325 members of the Black Watch who left the start-lines, only 15 answered evening roll-call. German counterattacks on 26 and 27 July pushed Canadian forces back to Point 67. However, the situation eventually eased for the 2nd Canadian Division when US forces went on the offensive. Throughout the first week of August, significant German resources were transferred from the Anglo-Canadian front to that of the U.S. Third Army, under Lieutenant General George Patton, while reinforcements moved from Pas de Calais to the Falaise–Calvados area. By 7 August 1944, only one major formation, the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend, faced Canadian forces on Verrières Ridge.

By 1 August 1944, the British had made significant gains on the Vire and Orne Rivers during Operation Bluecoat, while the Americans had achieved a complete breakthrough in the west. On 4 August, Simonds and General Harry Crerar—newly appointed commander of the First Canadian Army—were given the order to prepare an advance on Falaise. Three days later, with heavy bomber support, Operation Totalize began, marking the first use of Kangaroo Armoured Personnel Carriers. While the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division attacked east of the Caen–Falaise Road, 2nd Division attacked to the west. By noon Verrières Ridge had finally fallen, and Canadian and Polish armour was preparing to exploit south towards Falaise. However, strong resistance by the 12th SS Panzer Division and the 272nd Volksgrenadier Division halted the advance. Although 12 km (7.5 mi) of ground had been gained, Canadian forces had failed to reach Falaise itself.

Simultaneously, the Germans had launched Operation Luttich, a desperate and ill-prepared armoured thrust towards Mortain, beginning on 6 August 1944. This was halted within a day and, despite the increasingly dangerous threat presented by the Anglo–Canadian advance on Falaise, the German commander Field Marshal Günther von Kluge was prohibited by Hitler from redeploying his forces. Thus, as American armoured formations advanced towards Argentan from the south, the Allies were presented with an opportunity to encircle large sections of the German Seventh Army. The First Canadian Army was ordered south, while the Americans prepared to move on Chambois on 14 August. Simonds and Crerar quickly planned a further offensive that would push through to Falaise, trapping the German Seventh Army in Normandy.

Throughout September and October 1944, the First Canadian Army moved along the coast of France with the aim of securing the Channel Ports. On 1 September, while the 3rd Division made for Boulogne and Calais, the 2nd Division entered Dieppe, encountering virtually no resistance. Five days later they were tasked by Montgomery and Crerar with retaking Dunkirk. Heavy fighting around the outskirts would hold the division for several days but, by 9 September, the 5th Brigade had captured the port. The Dunkirk perimeter was handed over to the British on 15 September, and the 2nd Division made for Antwerp.

Although the Belgian White Brigade, the 11th Armoured Division, and elements of the British 3rd Infantry Division had entered Antwerp as early as 4 September, taking the city and docks, a strategic oversight meant that the nearby bridges over the Albert Canal were not seized, leaving the Germans in control of the Scheldt estuary. The failure to make an immediate push on the estuary ensured the strategically vital port would remain useless until the Scheldt was cleared. Strong formations of the German Fifteenth Army, which had withdrawn from the Pas de Calais, were able to consolidate their positions on the islands of South Beveland and Walcheren, as well as the Albert Canal directly northwest of Antwerp, and were further reinforced by elements of General Kurt Student’s First Parachute Army.

During the initial phases of the battle, the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division sought to force a crossing of the Albert Canal. On 2 October, the entire First Canadian Army—under the temporary command of General Simonds—moved against the German defences. Two days later, 2nd Division had cleared the canal, and was moving northwest towards South Beveland and Walcheren Island. On Friday, 13 October, later known as “Black Friday”, the 5th Brigade’s Black Watch attacked positions near the coast, losing all four company commanders and over 200 men. Three days later, the Calgary Highlanders conducted a more successful offensive, capturing the initial objective of Woensdrecht. Simultaneously, the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division and the 4th Canadian (Armoured) Division captured Bergen, cutting off South Beveland and Walcheren from reinforcement.

By November 1944, the First Canadian Army had entered the Nijmegen Salient which was being held for use in the development of future offensives. The 2nd Division came under the command of Major General Bruce Matthews, with Foulkes being transferred to command the I Canadian Corps on the Italian Front. The First Canadian Army launched no major offensive operations from November 1944 to January 1945; the longest hiatus the Canadians had enjoyed since landing on the Normandy beaches the previous June.

Operation Veritable was designed to bring the 21st Army Group to the west bank of the Rhine River, the last natural obstacle before entering Germany. Initially scheduled for December 1944, the operation was delayed until February by the German Ardennes Offensive. Plans were developed to breach three successive defensive lines: the outpost screen; a formidable section of the Siegfried Line running through the Hochwald Forest; and finally the Hochwald Layback covering the approach to the ultimate objective of Xanten. The first phase began on 8 February 1945, with the 2nd Division’s advance following up one of the largest artillery barrages seen on the Western Front. The Germans had prepared significant defences in depth, both within the outpost screen and the Siegfried Line itself, and to add to the Canadians’ difficulties, constant rain and cold weather obscured the battlefield. However, by the end of the first day, the 2nd Division had captured their objectives, the fortified towns of Wyler and Den Heuvel. On 11 February, the division moved southeast to assist British XXX Corps in their assault on Moyland Wood.

The operational plan’s second phase called for the 2nd and 3rd Divisions to take the Hochwald Forest. Following its capture, the 4th Canadian Armoured would sweep through the Hochwald Gap towards Wesel, followed by the 2nd Division “leap-frogging” towards Xanten. Operation Blockbuster was scheduled for 27 February, but despite initial gains, stubborn German resistance prolonged the battle for six days. It was not until 3 March that the forest was cleared—during the intense close-quarter fighting, Major Frederick Tilston of the Essex Scottish Regiment won a Victoria Cross.

Operation Blockbuster’s final phase was the attack on Xanten itself, which lasted from 8 to 10 March. This fell primarily to the 2nd Division and 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade, although the 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division was temporarily assigned to Simonds’s II Canadian Corps for the assault. Despite an elaborate preceding artillery barrage, dogged German resistance caused the battle to degenerate into one of attrition. Because effective air-support was prevented by fog and movement was hindered by German mortar barrages, the British and Canadians suffered heavy casualties. However, by 10 March, the 2nd Division’s 5th Brigade had linked up with elements of the 52nd (Lowland) Infantry Division, bringing the offensive to a close. Total Canadian casualties during Veritable and Blockbuster were 5,304 killed or wounded.

As Canadian forces had incurred heavy casualties in clearing a path to the Rhine, the 2nd Division was excluded from the massive crossing operation that took place on 23 March 1945, instead crossing unopposed a week later after a bridgehead had been secured. After a brief detour through German territory, the First Canadian Army, now unified with the arrival of I Canadian Corps from Italian Front, prepared to assault German positions in the Netherlands. The 2nd Division moved northwards towards Groningen. In the nine days preceding their attack, German resistance had been light and uncoordinated, but opposition stiffened as the assault progressed, leading to heavy losses among the battalions of the 5th Brigade. By 13 April, the division had been shifted eastward to guard the flanks of a British assault on Bremen, and the following day I Canadian Corps liberated Arnhem. On 2 May, the 2nd Division took Oldenburg, solidifying Canadian positions throughout the Netherlands. German and Canadian forces declared a ceasefire on 5 May, and all fighting came to an end with the surrender of German forces in Western Europe on 7 May 1945. In October 1945, after four months in the Netherlands, General Order 52/46 officially disbanded the headquarters of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division. By December, the entirety of the division had been stood down and returned to Canada. The division suffered heavy casualties through 1944 and 1945; according to Bercuson it had the “highest casualty ratio in the Canadian Army – from the time it returned to combat in early July 1944 until the end of the war”.

The following officers commanded the division:

Major General Victor Odlum (1940–1941)

Major General Harry Crerar (1941–1942)

Major General John Roberts (1941–1943)

Major General Guy Simonds (1943)

Major General Eedson Burns (1943–1944)

Major General Charles Foulkes (1944)

Major General Bruce Matthews (1944–1945)

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3224243)

General Crerar visiting General Matthews of 2 Division at 2 Division Headquarters near Millingen, Netherlands, 31 March 1945.

Order of Battle for the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, 1944

4th Canadian Infantry Brigade

The Royal Regiment of Canada

The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry (Wentworth Regiment)

The Essex Scottish Regiment

4th Infantry Brigade Ground Defence Platoon (Lorne Scots)

5th Canadian Infantry Brigade

The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada

Le Régiment de Maisonneuve

The Calgary Highlanders

5th Infantry Brigade Ground Defence Platoon (Lorne Scots)

6th Canadian Infantry Brigade

The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada

The South Saskatchewan Regiment

Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal

6th Infantry Brigade Ground Defence Platoon (Lorne Scots)

Support units

The Toronto Scottish Regiment (machine gun)

8th Reconnaissance Regiment (14th Canadian Hussars) (8 Recce)

Royal Canadian Artillery

Headquarters

4th Field Regiment, 2nd (Ottawa) Field Battery, 14th (Midland) Field Battery, 26th (Lambton) Field Battery, 5th Field Regiment, 5th (Westmount) Field Battery, 28th (Newcastle) Field Battery, 73rd Field Battery, 6th Field Regiment, 13th (Winnipeg) Field Battery, 21st Field Battery, 91st Field Battery

2nd Anti-Tank Regiment, 18th Anti-Tank Battery, 20th Anti-Tank Battery, 23rd Anti-Tank Battery, 108th Anti-Tank Battery, 3rd Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, 16th Light Anti-Aircraft Battery, 17th Light Anti-Aircraft Battery, 38th Light Anti-Aircraft Battery

Corps of Royal Canadian Engineers

Headquarters

1st Field Park Company, 2nd Field Company, 7th Field Company, 11th Field Company, one bridging platoon

Royal Canadian Corps of Signals

2nd Canadian Divisional Signals

Royal Canadian Army Service Corps

Headquarters

4th Infantry Brigade Company, 5th Infantry Brigade Company, 6th Infantry Brigade Company, Second Infantry Divisional Troops Company

Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps

No. 10 Field Ambulance, No. 11 Field Ambulance, No. 18 Field Ambulance, 13th Canadian Field Hygiene Section, 4th Canadian Field Dressing Station, 21st Canadian Field Dressing Station

Royal Canadian Ordnance Corps

No. 2 Infantry Division Ordnance Field Park

Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers

Headquarters

4th Infantry Brigade Workshop, 5th Infantry Brigade Workshop, 6th Infantry Brigade Workshop, one LAA workshop

Eleven light aid detachments.

Canadian Provost Corps

No. 2 Provost Company

2nd Canadian Infantry Division, Photographs from the Library and Archives Canada Collection

The Royal Regiment of Canada

The regiment mobilized the Royal Regiment of Canada, CASF (Canadian Active Service Force), for active service on 1 September 1939. It embarked for garrison duty in Iceland with “Z” Force on 10 June 1940, and on 31 October 1940 it was transferred to Great Britain. It was redesignated the 1st Battalion, the Royal Regiment of Canada, CASF, on 7 November 1940 when a 2nd Battalion was formed to provide reinforcements to the Regiment in Europe. The 1st battalion took part in the raid on Dieppe on 19 August 1942. It landed again in France on 7 July 1944, as part of the 4th Infantry Brigade, 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, and continued to fight in North West Europe until the end of the war. The 1st battalion was disbanded on 31 December 1945 when it amalgamated with the 2nd Battalion back home.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3209320)

Infantrymen of “D” Company, Royal Regiment of Canada, supported by a Sherman tank of the Fort Garry Horse, advance from Hatten to Dingstede, Germany, 24 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3209746)

A signalman of The Royal Regiment of Canada with a No.18 wireless set near Dingstede, Germany, 25 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3209321)

Infantrymen of “D” Company, Royal Regiment of Canada, examine equipment taken from surrendering German soldiers during the advance from Hatten to Dingstede, Germany, 24 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3299067)

Corporal W.E. Oliver, Royal Regiment of Canada, directing mortar fire, watched by Private J. Keller, driver of their Universal Carrier, France, 28 September 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3525067)

Infantrymen of The Royal Regiment of Canada resting after a long march, Blankenberghe, Belgium, 11 September 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3209320)

Infantrymen of “D” Company, Royal Regiment of Canada, supported by a Sherman tank of the Fort Garry Horse, advance from Hatten to Dingstede, Germany, 24 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3209321)

Infantrymen of “D” Company, Royal Regiment of Canada, examine equipment taken from surrendering German soldiers during the advance from Hatten to Dingstede, Germany, 24 April 1945.

(Stuart Phillips Photo)

The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry (Wentworth Regiment)

The regiment mobilized the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry, CASF for active service on 1 September 1939. It was redesignated as the 1st Battalion, the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry, CASF on 7 November 1940. It embarked for Britain on 22 July 1940. The battalion took part in Operation Jubilee on 19 August 1942. (General Denis Whitaker, who fought as a captain with the RHLI at Dieppe, in a 1989 interview stated, “The defeat cleared out all the dead weight. It was the best thing that ever happed to the regiment.) The RHLI returned to France on 5 July 1944 as part of the 4th Infantry Brigade, 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, and continued to fight in North West Europe until the end of the war. The overseas battalion was subsequently disbanded on 31 December 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3205115)

Infantrymen of The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry in General Motors C15TA armoured trucks, Krabbendijke, Netherlands, 27 October 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3524891)

Infantrymen of The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry passing wrecked German wagons, Elbeuf, France, 27 August 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3577399)

Canadians of the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry meeting Americans of the U.S. Army’s 2nd Armoured Division, Elbeuf, France, 27 August 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3199698)

Infantrymen of The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry riding in a Universal Carrier, Krabbendijke, Netherlands, 27 October 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3199228)

Infantrymen of The Highland Light Infantry of Canada resting alongside the Orne River en route to Caen, France, 18 July 1944.

(Stuart Phillips Photo)

The Essex Scottish Regiment

During the Second World War, the regiment was among the first Canadian units to see combat in the European theatre during the invasion of Dieppe. By the end of The Dieppe Raid, the Essex Scottish Regiment had suffered 121 fatal casualties, with many others wounded and captured. The Essex Scottish later participated in Operation Atlantic and was slaughtered attempting to take Verrières Ridge on 21 July. By the war’s end, the Essex Scottish Regiment had suffered over 550 war dead; its 2,500 casualties were the most of any unit in the Canadian army during the Second World War.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3205594)

The Essex Scottish Regiment in Universal Carriers, ready for loading onto Buffalo amphibious vehicles, 13 April 1945.

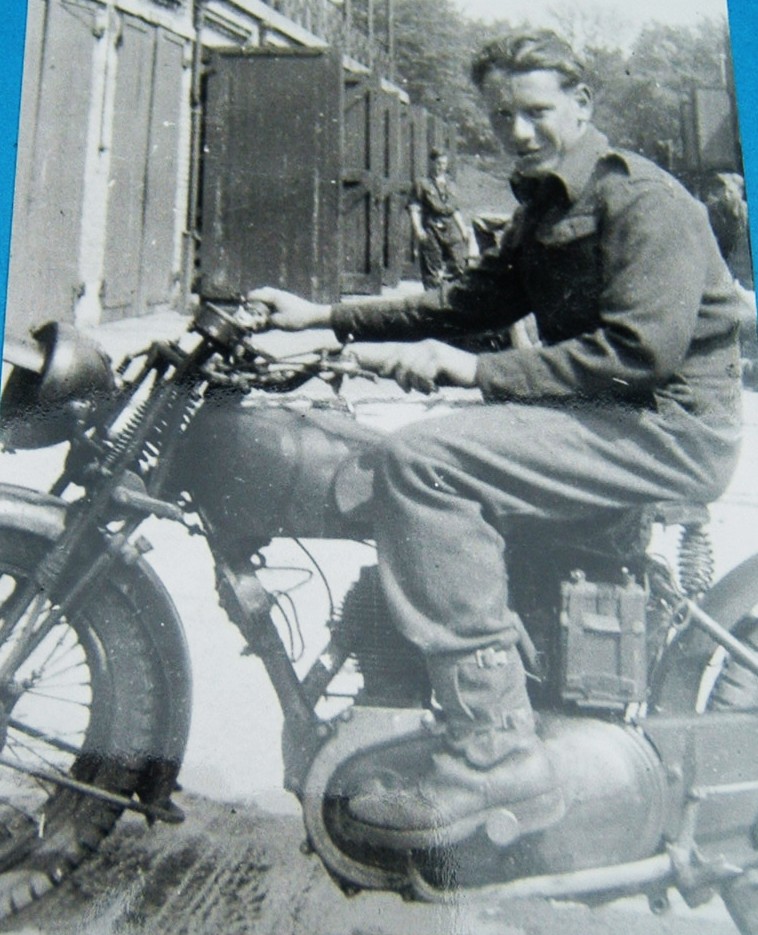

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3208311)

Private L. Wilkins of the Essex Regiment resting on his motorcycle, 14 April1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3524539)

Lance-Corporal J.E. Cunningham of The Essex Scottish Regiment practices firing a Lifebuoy flamethrower near Xanten, Germany, 10 March 1945

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3396411)

Infantrymen of The Essex Scottish Regiment lying in a ditch to avoid German sniper fire en route to Groningen, Netherlands, 14 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3224251)

Fifteen German prisoners of war captured by the Essex Scottish Regiment during the attack on Zetten and Hemmen, the Netherlands.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3524165)

Captain Fred A. Tilston of The Essex Scottish Regiment near Caen, France, 5 August 1944. He was a Canadian recipient of the Victoria Cross.

On 1 March 1945, near Uedem, Germany, he led “C” Company in a 500-yard attack across muddy terrain soaked by recent rain and snow, through barbed wire and enemy automatic weapons fire. After being slightly wounded by shell fragments in the head, he personally destroyed one enemy machine gun position with a hand grenade, and led the men of C company on to a second German line of resistance when he was wounded for the second time in the hip. He struggled to his feet and led his men forward where the Essex Scottish overran the enemy positions with rifle butts, bayonets and knives in close hand-to-hand combat. While consolidating the Canadian position against German counterattacks and on his 6th trip from a neighbouring unit bringing ammunition and grenades to his company, which had been depleted to about 25% of its usual strength or 40 men, Tilston was wounded for the 3rd time in the leg. He was found almost unconscious in a shell hole and refused medical attention while he organized his men for defence against German counter-attacks, emphasized the necessity of holding the position at all cost, and ordered his one remaining officer to take command. For conspicuous gallantry and steadfast determination in the face of battle, Tilston was awarded the Victoria Cross.

(Stuart Phillips Photo)

The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada

The regiment mobilized the 1st Battalion, The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada, CASF, on 1 September 1939. This unit, which served in Newfoundland from 22 June to 11 August 1940, embarked for Great Britain on 25 August 1940. Three platoons took part in the raid on Dieppe on 19 August 1942. On 6 July 1944, the battalion landed in France as part of the 5th Infantry Brigade, 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, and it continued to fight in North West Europe until the end of the war. The overseas battalion was disbanded on 30 November 1945.

The 1st Battalion suffered more casualties than any other Canadian infantry battalion in Northwest Europe according to figures published in The Long Left Flank by Jeffrey Williams. On the voyage to France on the day of the Dieppe Raid, casualties were suffered by the unit during a grenade priming accident on board their ship, HMS Duke of Wellington. During the Battle of Verrières Ridge on 25 July 1944, 325 men left the start line and only 15 made it back to friendly lines, the others being killed or wounded by well-entrenched Waffen SS soldiers and tanks. On 13 October 1944 – known as Black Friday by the Black Watch – the regiment put in an assault near Hoogerheide during the Battle of the Scheldt in which all four company commanders were killed, and one company of 90 men was reduced to just four survivors.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3590885)

Infantrymen of “B” Company, The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada, firing a three-inch mortar, Groesbeek, Netherlands, 3 February 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3613491)

Soldiers with the Black Watch of Canada training with a 6-pounder anti-tank gun. Note the Lee-Enfield rifle used as a small calibre aiming device.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3203511)

Infantrymen of “C” Company, The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada, gathered around a slit trench in the woods near Holten, Netherlands, 8 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3396388)

Infantry of the Black Watch of Canada (Royal Highland Regiment) crossing the river Regge south of Ommen, Netherlands, 10 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3524613)

Black Watch ‘B’ Company men in a location overlooking the German Lines. Left to right: Cpl. Joe Hanson and Ptes. Ralph Glasier, Lew Wasnick and Doug Knight, Groesbeek, Netherlands, 3 February 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3230698)

American-born members of Support Company, The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada, South Beveland, Netherlands, 30 September 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 4232588)

Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, inspecting the The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada, 1943.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3205164)

C Company commander, 5 Brigade Black Watch, Captain W.L. Barnes checks map reference with signalman Pte H. Howard, 8 April 1945.

(Stuart Phillips Photo)

1997.28.549.

Le Régiment de Maisonneuve

The regiment mobilized Le Régiment de Maisonneuve, CASF, on 1 September 1939. It embarked for Great Britain on 24 August 1940. It was redesignated as the 1st Battalion, Le Régiment de Maisonneuve, CASF, on 7 November 1940. 17 On 7 July 1944, the battalion landed in France as part of the 5th Infantry Brigade, 2nd Canadian Infantry Division. It suffered heavy casualties in the Battle of the Scheldt, and was notably depleted by the time of the Battle of Walcheren Causeway. The unit recovered during the winter and was again in action during the Rhineland fighting and the final weeks of the war, taking part in the final campaigns in northern Netherlands, the Battle of Groningen, and the final attacks on German soil. The overseas battalion was disbanded on 15 December 1945.

.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3207886)

Lieutenant Louis Woods of Le Régiment de Maisonneuve observing a German position during Operation VERITABLE near Nijmegen, Netherlands, 8 February 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3524835)

Privates Arthur Richard and Aurele Nantel of the Regimental Aid Party, Le Régiment de Maisonneuve, treating a wounded soldier near the Maas River, Cuyk, Netherlands, 23 January 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3392829)

GM C15TA Armoured Truck CZ428917 ‘Aristocrat’ near Nijmegen, Netherlands, 5 December 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. )

Corporal C. Robichaud of Le Régiment de Maisonneuve examining a disabled German Sturmhaubitz 42 105-mm self-propelled gun, Woensdrecht, Netherlands, 27 October 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3210492)

A two inch mortar crew in action – Privates Raoul Archambault and Albert Harvey of Le Régiment de Maisonneuve, 23 January 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3225204)

Regiment de Maisonneuve during the attack on the Western Front, 8 Feb 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3524187)

Infantrymen of Le Régiment de Maisonneuve riding on a Sherman tank of The Fort Garry Horse entering Rijssen, Netherlands, 9 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3205241)

Infantry of the Regiment de Maisonneuve moving through Holten to Rijssen, both towns in the Netherlands, 9 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3529264)

Private R. Langlois of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division examining a collection of captured German weapons, which include a Panzerfaust anti-tank weapon, near the Hochwald, Germany, 3 March 1945.

The Calgary Highlanders

The regiment mobilized for active service as The Calgary Highlanders, Canadian Active Service Force (CASF) on 1 September 1939. It was re-designated as the 1st Battalion, The Calgary Highlanders, CASF, on 7 November 1940. On 27 August 1940, it embarked for Britain. The battalion’s mortar platoon took part in the Dieppe Raid on 19 August 1942. On 6 July 1944, the battalion landed in France as part of the 5th Canadian Infantry Brigade, 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, and it continued to fight in North West Europe until the end of the war. The regiment selected the Battle of Walcheren Causeway for annual commemoration after the war. The overseas battalion disbanded on 15 December 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3358102)

Corporal Frank Maguire of The Calgary Highlanders manning a machine gun in a Universal Carrier near Doetinchem, Netherlands, 1 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3227193)

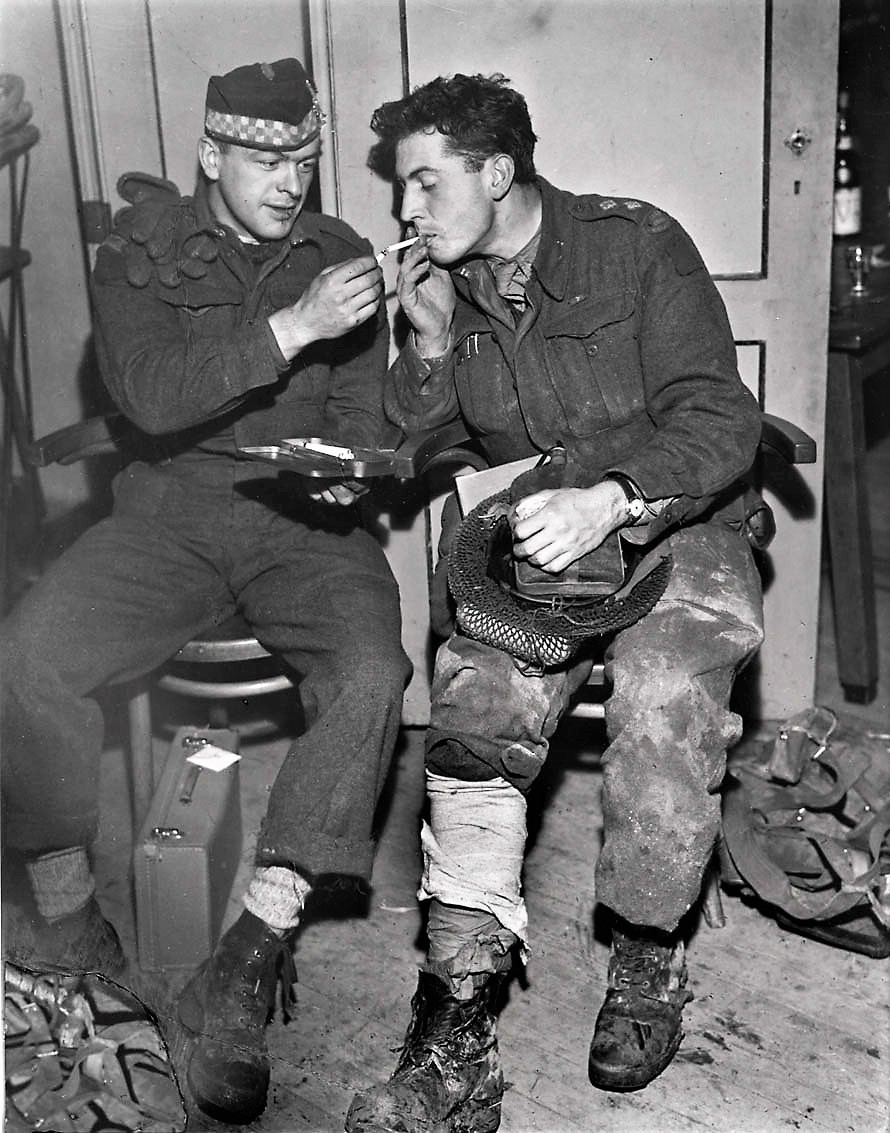

Private D. Tillick of the Toronto Scottish Regiment (M.G.) and Lieutenant T.L. Hoy of the Calgary Highlanders, who both were wounded on the causeway between Beveland and Walcheren, waiting for treatment at the Casualty Clearing Post of the 18th Field Ambulance, Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps (RCAMC), Netherlands, 1 November 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3405373)

Infantrymen of The Calgary Highlanders, Doetinchem, Netherlands, 1 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3358102)

Corporal Frank Maguire of The Calgary Highlanders manning a machine gun in a Universal Carrier near Doetinchem, Netherlands, 1 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3231598)

Private M. Voske and Private H. Browne of The Calgary Highlanders examinea captured German radio-controlled Goliath remote controlled demolition vehicle, Goes, Netherlands, 30 October 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3596657)

Corporal S. Kormendy and Sergeant H.A. Marshall of The Calgary Highlanders cleaning the telescopic sights of their No. 4 Mk. I(T) rifles during a scouting, stalking and sniping course, Kapellen, Belgium, 6 October 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3206370)

Sergeant Harold Marshall, of the Calgary Highlanders Scout and Sniper Platoon, posing for Army photographer Ken Bell near Fort Brasschaet, Belgium, September 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3521073)

A Calgary Highlanders soldier servicing a No. 18 wireless set, Pagham, England, 20 January 1943.

Royal

The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada

The regiment mobilized The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada, CASF for active service on 1 September 1939. It was redesignated as the 1st Battalion, The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada, CASF on 7 November 1940. It embarked for Great Britain on 12 December 1940. The battalion took part in Operation Jubilee, the Dieppe Raid, on 19 August 1942. It returned to France on 7 July 1944, as part of the 6th Infantry Brigade, 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, and it continued to fight in North West Europe until the end of the war. The overseas battalion disbanded on 30 November 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3230012)

Universal Carriers of The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada preparing to move from Germany to the Netherlands. Leer, Germany, 11 July 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 5180146)

Pte. J.E. Kirby of The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada stands guard over a V-2 rocket motor near the Antwerp Docks, Netherlands, 15 Oct 1942.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3199694)

Scouts of The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada, Camp de Brasschaet, Belgium, 9 October 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3209748)

Infantrymen of Support Company, The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada, supported by a Sherman tank of The Fort Garry Horse, advancing south of Hatten, Germany, 22 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3524541)

Wounded infantrymen of Support Company, The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada, being helped to cover south of Kirchatten, Germany, ca. 22 April 1945.

(Stuart Phillips Photo)

The South Saskatchewan Regiment

During the Second World War, The South Saskatchewan Regiment participated in many major Canadian battles and operations, as part of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division. The South Saskatchewan Regiment fought in the Dieppe Raid of 1942, Operation Atlantic, Operation Spring, Operation Totalize, Operation Tractable, and the recapture of Dieppe in 1944. They, along with the 8th Reconnaissance Regiment liberated the Westerbork transit camp on 12 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3520709)

Infantrymen of The South Saskatchewan Regiment firing through a hedge during mopping-up operations along the Oranje Canal, Netherlands, 12 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 49358)

Regimental Aid Party of The South Saskatchewan Regiment resting on the southern bank of a canal north of Laren, Netherlands, 7 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3396365)

Infantrymen of The South Saskatchewan Regiment during mopping-up operations along the Oranje Canal, 12 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3205112)

German prisoners guarded by infantrymen of The South Saskatchewan Regiment, Hoogerheide, Netherlands, 15 October 1944

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3396197)

Personnel of the South Saskatchewan Regiment in captured Germany. ‘Schwimmwagen’ amphibious car of the Wehrmacht, Rocquancourt, France, 11 August 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3396200)

Private G.O. Parenteau of The South Saskatchewan Regiment, Rocquancourt, France, 11 August 1944.

Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal

The regiment mobilized the Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal, CASF for active service on 1 September 1939. It was redesignated as the 1st Battalion, Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal, CASF on 7 November 1940. It embarked for garrison duty in Iceland with “Z” Force on 1 July 1940. On 31 October 1940 it was transferred to Great Britain. The regiment took part in OPERATION JUBILEE, the raid on Dieppe on 19 August 1942. It returned to France on 7 July 1944, as part of the 6th Infantry Brigade, 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, and it continued to fight in North West Europe until the end of the war. The overseas battalion was disbanded on 15 November 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3209740)

Tactical Headquarters of Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal, 29 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3524542)

Infantry of Les Fusiliers de Mont-Royal Regiment taking cover between two tanks during attack in the vicinity of Oldenburg, Germany, 29 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3209183)

Infantry of Les Fusiliers de Mont-Royal Regiment clearing out snipers in Normandy, 14 August 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3228083)

Sherman tanks of “C” Squadron, The Fort Garry Horse, passing infantrymen of Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal, Munderloh, Germany, 29 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3226042)

Infantrymen of Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal loading Sten gun magazines, Munderloh, Germany, 29 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3262650)

Infantrymen of Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal in front of a statue of Frederick the Great, Berlin, Germany, 14 July 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3228879)

Infantrymen of Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal drawing water from a well near Laren, Netherlands, 6 April 1945.

The Toronto Scottish Regiment (Machine Gun)

During the Second World War, the regiment initially mobilized a machine gun battalion for the 1st Canadian Infantry Division. Following a reorganization early in 1940, the battalion was reassigned to the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, where it operated as a support battalion, providing machine-gun detachments for the Operation Jubilee force at Dieppe in 1942, and then with an additional company of mortars, it operated in support of the rifle battalions of the 2nd Division in northwest Europe from July 1944 to VE Day. In April 1940, the 1st Battalion also mounted the King’s Guard at Buckingham Palace. The 2nd Battalion served in the reserve army in Canada.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3262696)

Soldiers of the Toronto Scottish Regiment in their Universal Carrier waiting to move forward, Nieuport, Belgium, 9 September 1944.

Dave Blocksidge family Photo)

Pte. Ronald Blocksidge fought through Europe with the Toronto Scottish during the Second World War.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3204241)

A German armoured car dug into the ground and used as a pillbox fortification, Nieuport, Belgium, 9 September 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3524442)

Private L.P. McDonald and Lance-Corporals W. Stevens and R. Dais, all of the Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA), manning a six-pounder anti-tank gun, Nieuport, Belgium, 9 September 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3199687)

Personnel of The Toronto Scottish Regiment (M.G.) aboard a motorboat en route from Beveland to North Beveland, Netherlands, 1 November 1944.

(Stuart Phillips Photo)

8th Reconnaissance Regiment (14th Canadian Hussars) (8 Recce)

8 Recce was formed at Guillemont Barracks, near Aldershot in southern England, on 11 March 1941, by merging three existing squadrons within the division. Its first commanding officer was Lieutenant Colonel Churchill C. Mann. Mann was succeeded as commanding officer on 26 September 1941, by Lieutenant Colonel P. A. Vokes, who was in turn followed on 18 February 1944, by Lieutenant Colonel M. A. Alway. The last commanding officer was Major “Butch” J. F. Merner, appointed to replace Alway a couple of months before the end of the fighting in Europe.

8 Recce spent the first three years of its existence involved in training and coastal defence duties in southern England. It was not involved in the ill-fated Dieppe Raid on 19 August 1942, and thus avoided the heavy losses suffered that day by many other units of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division. The regiment landed with its division in Normandy on 6 July 1944, one month after D-Day, and first entered combat as infantry in the ongoing Battle of Normandy. The regiment’s first three combat deaths occurred on 13 July, two of which when a shell struck a slit trench sheltering two men near Le Mesnil. Another Trooper was killed during the Battle of Caen the same day from a mortar shell.

Following the near-destruction of the German Seventh Army and Fifth Panzer Army in the Falaise Pocket in August 1944, the remaining German forces were compelled into a rapid fighting retreat out of Northern France and much of Belgium. 8 Recce provided the reconnaissance function for its division during the advance of the First Canadian Army eastward out of Normandy, up to and across the Seine River, and then along the coastal regions of northern France and Belgium. The regiment was involved in spearheading the liberation of the port cities of Dieppe and Antwerp; it was also involved in the investment of Dunkirk, which was then left under German occupation until the end of war. 8 Recce saw heavy action through to the end of the war including the costly Battle of the Scheldt, the liberation of the Netherlands and the invasion of Germany.

An early demonstration of the mobility and power of the armoured cars of 8 Recce occurred during the liberation of Orbec in Normandy. Over the period 21-23 August, the infantry of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division had succeeded in pushing eastward up to the west bank of the River Tourques, but they were unable to expand an initial bridgehead across the river because of the presence of enemy positions in Orbec on the east bank. Humbers of 8 Recce had meanwhile scouted out possible river crossings northwest of the town. They succeeded in crossing the Tourques, then circled back to Orbec and attacked the German defenders unexpectedly from the north and east. Enemy resistance in the town was rapidly overcome and the division’s advance towards the Seine could resume.

The reconnaissance role of 8 Recce often put its members well ahead of the main body of the division, especially during the pursuit of the retreating German army across northern France and Belgium in late August and September 1944. For example, elements of 8 Recce entered Dieppe on the morning of 1 September 1944, scene of the disastrous Dieppe Raid of 1942, a full 12 hours before the arrival of truck-borne Canadian infantry. The liberation of Dieppe was facilitated by the withdrawal of the German occupying forces on the previous day. The unexpectedly early liberation allowed a planned and likely devastating Allied bombing raid on the city to be called off. 8 Recce was responsible for liberating many other towns in the campaign across Northwest Europe.

During the Battle of the Scheldt, 8 Recce advanced westwards and cleared the southern bank of the West Scheldt river. In one notable action, armoured cars of ‘A’ Squadron were ferried across the river; on the other side the cars then proceeded to liberate the island of North Beveland by 2 November 1944. Bluff played an important role in this operation. The German defenders had been warned that they would be attacked by ground support aircraft on their second low-level pass if they did not surrender immediately. Shortly thereafter 450 Germans surrendered after their positions were buzzed by 18 Typhoons. Unbeknownst to the Germans, the Typhoons would not have been able to fire on their positions since the aircraft’s munitions were already committed to another operation.

Shortly after midnight on the night 6–7 February 1945 (Haps, Holland), when 11 and 12 troops of C Squadron patrolled and contacted each other and started back – 11 troop patrol was challenged with halt from, the ditch. L/Cpl. Bjarne Tangen fired a sten magazine into the area from which the challenge came and then he and the others quickly took-up positions in the ditch, while the 3rd member of their patrol ran back and collected the 12 troop patrol, together with reinforcements from 12 troop and returned to the scene of firing. The evening ended with the patrol taking one German prisoner and one deceased. The German prisoner, Lt. Gunte Finke, was interrogated and he disclosed that he gave himself up after seeing the response of an estimated 30 men from the skirmish. The German intention was to verify information that armoured cars were in the area; not to bother with foot patrol or prisoners, but to attempt to “Bazooka one of our vehicles with the 2 Panzerfaust that their patrols carried”. L/Cpl.Tangen was awarded the Dutch Bronze Cross, and Mentioned in dispatches, for this event.

On 12 April 1945, No. 7 Troop of ‘B’ Squadron liberated Camp Westerbork, a transit camp built to accommodate Jews, Romani people and other people arrested by the Nazi authorities prior to their being sent into the concentration camp system. Bedum, entered on 17 April 1945, was just one of many Dutch towns liberated by elements of 8 Recce in the final month of the war.

8 Recce’s last two major engagements were the Battle of Groningen over 13–16 April and the Battle of Oldenburg, in Germany, over 27 April to 4 May. Three members of 8 Recce were killed on 4 May, just four days before VE Day, when their armoured car was struck by a shell.

During the war 79 men were killed outright in action while serving in 8 Recce, and a further 27 men died of wounds.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3524797)

8th Reconnaissance Regiment Recce vehicles of the 2 Canadian Infantry Division on barges performing an amphibious operation, from Beveland Peninsula to North Beveland Island from just north of Oostkerke, Netherlands, 1 November 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3237870)

A Universal Carrier of the 8th Reconnaissance Regiment (14th Canadian Hussars), being loaded aboard a barge en route from South Beveland to North Beveland, Netherlands, 1 November 1944.