Battle of Hong Kong, New Brunswick Soldiers serving with the Royal Rifles of Canada

In late 1941, the British government accepted an offer by the Canadian Government to send a battalion of the Royal Rifles of Canada (based in Quebec) and one from the Winnipeg Grenadiers (based in Manitoba) and a brigade headquarters (1,975 personnel) to reinforce the Hong Kong garrison. “C Force”, as it was known, arrived on 16 November on board the A total of 96 officers, two Auxiliary Services supervisors and 1,877 other ranks disembarked. Included were two medical officers and two nurses (to the regimental medical officers), two Canadian Dental Corps officers with assistants, three chaplains and a detachment of the Canadian Postal Corps. A soldier of the (RCAMC), had stowed away nd was sent back to Canada.

The Royal Rifles had served only in the province of New Brunswick on coastal defence (where more than 400 Maritimers were recruited), and in the Dominion of Newfoundland, prior to posting to Hong Kong. The Winnipeg Grenadiers had been deployed to Jamaica Few Canadian soldiers had field experience, but were nearly fully equipped. However, the battalions had only two anti-tank rifles, and no ammunition for 2-inch and 3-inch mortars or for signal pistols. These were intended to be supplied after they arrived in Hong Kong. Nor did C Force receive its vehicles, as the US merchant ship San Jose carrying them was, at the outbreak of the Pacific War, diverted to Manila, in the, at the request of the US Government.

Royal Rifles of Canada logo. In the Second World War, Canadian soldiers first engaged in battle while defending the British Crown Colony of Hong Kong against a Japanese attack in December 1941. The Canadians at Hong Kong fought against overwhelming odds and displayed the courage of seasoned veterans, though most had limited military training. They had virtually no chance of victory, but refused to surrender until they were overrun by the enemy. Those who survived the battle became prisoners of war (POWs) and many endured torture and starvation by their Japanese captors.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3224662)

Winnipeg Grenadiers and Corps Troops entraining to head to the transport ship, en route to Hong Kong, 25 Oct 1941.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3393597)

The Royal Rifles of Canada boarding HMCS Prince Robert, enroute to Hong Kong, 26 Oct 1941.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3241498)

The Royal Rifles of Canada with mascot Gander en route to Hong Kong, 27 Oct 1941. In the Battle of Hong Kong two months later, Gander the dog was killed in action when running away with a picked up grenade thrown towards the Royal Rifles of Canada. For this act, Gander was posthumously awarded the Dickin Medal, the “animals’ Victoria Cross”.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3228792/PA-166999)

The Royal Rifles of Canada, C Coy, HMCS Prince Robert enroute to Hong Kong, 15 Nov 1941.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3396534/PA-114820)

The Royal Rifles of Canada, C Coy, disembarking from HMCS Prince Robert, Hong Kong, 16 Nov 1941.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3643012)

The Royal Rifles of Canada, C Coy, disembarking from HMCS Prince Robert, Hong Kong, 16 Nov 1941.

In October 1941, the Royal Rifles of Canada and the Winnipeg Grenadiers were ordered to prepare for service in the Pacific. From a national perspective, the choice of battalions was ideal. The Royal Rifles were a bilingual unit from the Quebec City area and, together with the Winnipeg Grenadiers, both battalions represented eastern and western regions of Canada. Command of the Canadian force was assigned to Brigadier J.K. Lawson. This was also a good choice because of Lawson’s training and experience; he was a “Permanent Force” officer and had been serving as Director of Military Training in Ottawa. The Canadian contingent was comprised of 1,975 soldiers, which also included two medical officers, two Nursing Sisters, two officers of the Canadian Dental Corps with their assistants, three chaplains, two Auxiliary Service Officers, and a detachment of the Canadian Postal Corps. There was also one military stowaway who was sent back to Canada.

(IWM Photo)

The Winnipeg Grenadiers at Hong Kong on the day of their arrival, 16 November 1941 (pictured), after spending 20 days on HMT Awatea, departed from Vancouver on 27 October. Under sealed orders, most did not know their port of destination until arriving Hong Kong. The Canadian politicians and military expected these troops would see only garrison (non-combat) duty, however, within three weeks of arrival, the Battle of Hong Kong began. The commander of the Winnipeg Grenadiers was L. Col.John Louis Robert Sutcliffe (29 August 1898, Elland, England – 6 April 1942, Hong Kong).

Prior to duty in Hong Kong, the Royal Rifles had served in Newfoundland and Saint John, New Brunswick, while the Winnipeg Grenadiers had been posted to Jamaica. In these locations, both battalions had received only minimal training. In late 1941, war with Japan was not considered imminent and it was expected that the Canadians would see only garrison (non-combat) duty. Instead, in December, the Japanese military launched a series of attacks on Pearl Harbor, Northern Malaya, the Philippines, Guam, Wake Island and Hong Kong. The Royal Rifles and the Winnipeg Grenadiers would find themselves engulfed in hand-to-hand combat against the Japanese 38th Division.

(IWM Photo, KF 189)

Canadian soldiers on exercise in the hills on Hong Kong Island before the Japanese invasion.

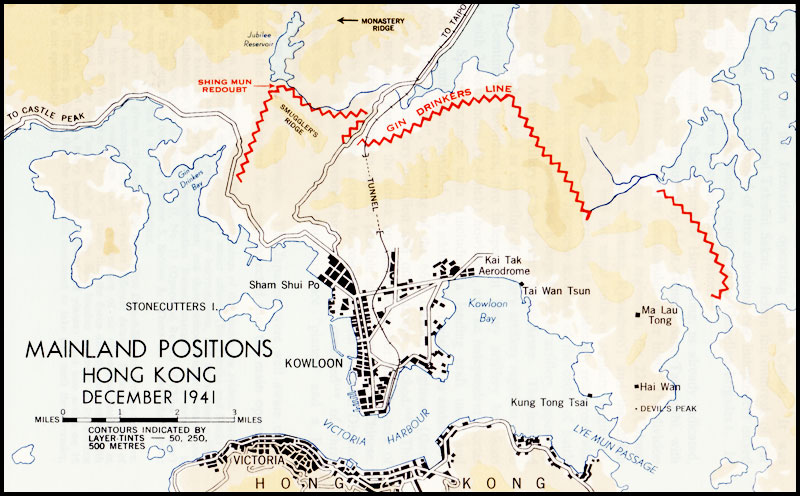

Mainland Positions, Hong Kong, December 1941 (C.P. Stacey, Six Years of War, Map 6).

C. C. J. Bond / Historical Section, General Staff, Canadian Army – Stacey, C. P., maps drawn by C. C. J. Bond (1956) [1955]. Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War. Volume I: Six Year of War: The Army in Canada, Britain and the Pacific(PDF). (2nd rev. online ed.). Ottawa: By Authority of the Minister of National Defence. OCLC 917731527). Map compiled and drawn by Historical Section, General Staff, Canadian Army.

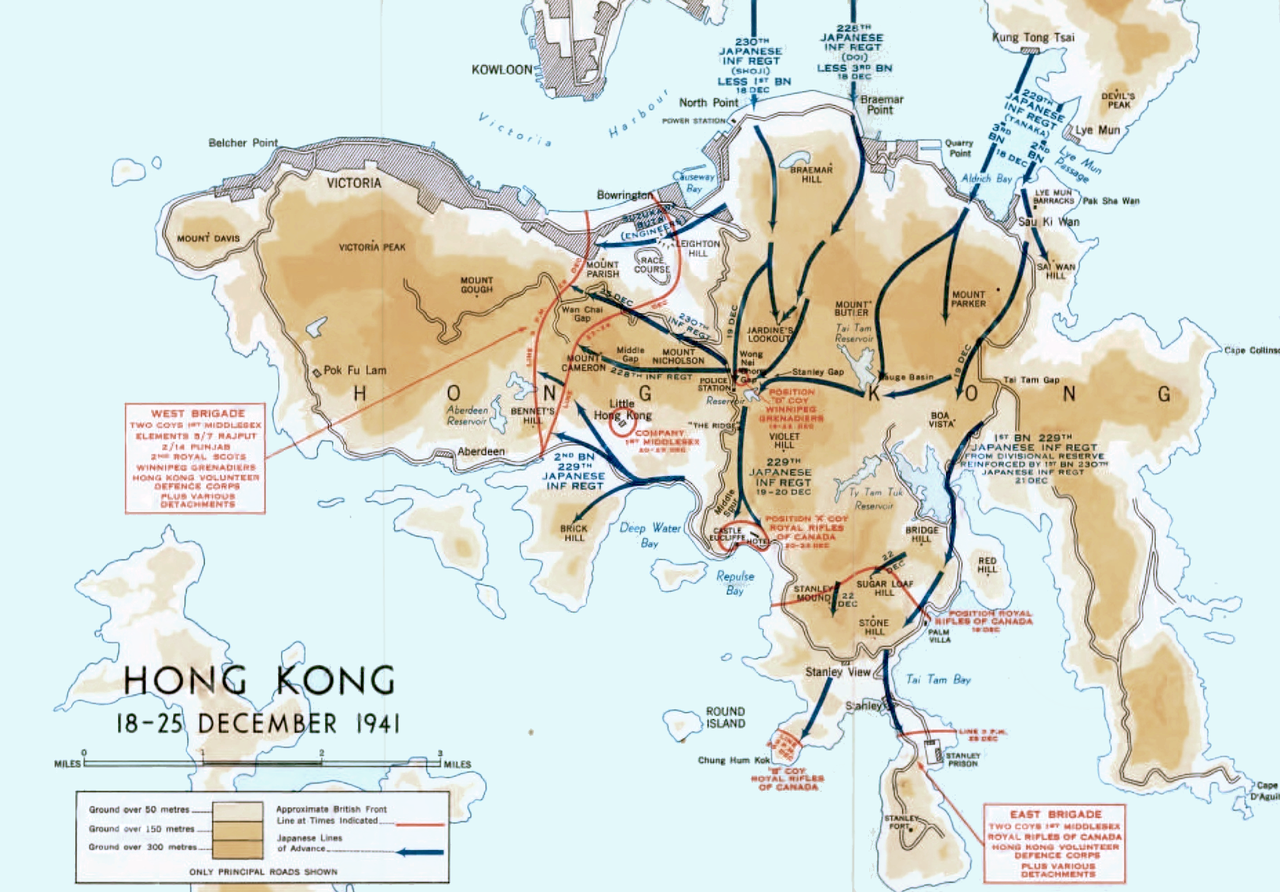

Maps of the Battle of Hong Kong Island, 18-25 December 1941.

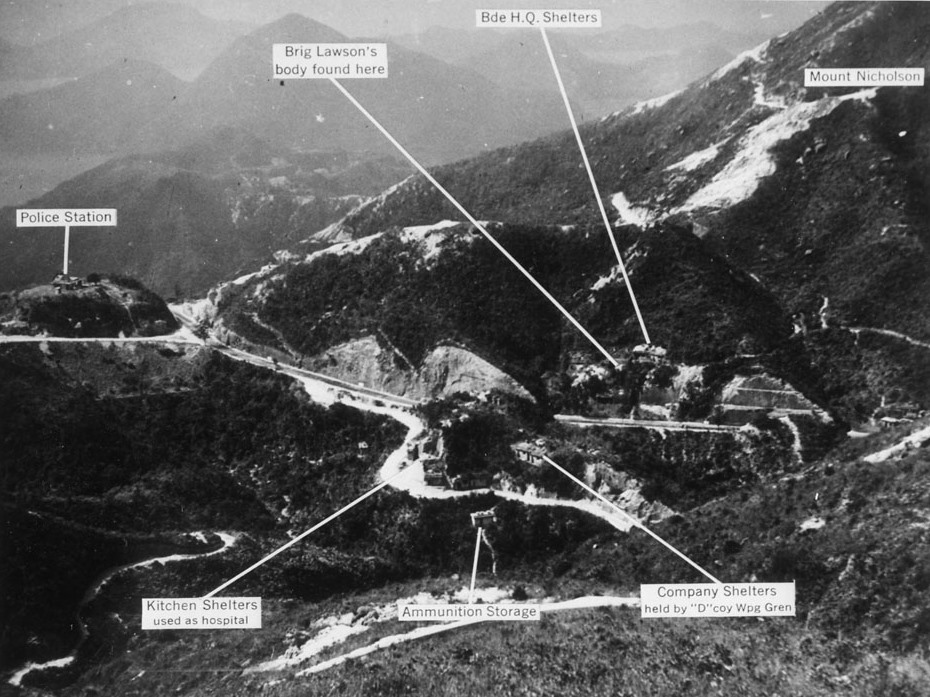

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3995680)

Hong Kong defences, site at Wong Nai Chong Gap where West Brigade Headquarters, and Winnipeg Grenadiers were over-run by Japanese forces, 19 Dec 1941.

The defence of Hong Kong was made at a great human cost. Approximately 290 Canadian soldiers were killed in battle and, while in captivity, approximately 264 more died as POWs, for a total death toll of 554. In addition, almost 500 Canadians were wounded. Of the 1,975 Canadians who went to Hong Kong, more than 1,050 were either killed or wounded. This was a casualty rate of more than 50%, arguably one of the highest casualty rates of any Canadian theatre of action in the Second World War.

New Brunswick Soldiers in Hong Kong, December 1941

The winter of December 1941 was a hard one for Canada and its allies. The Japanese attack on the Hawaiian Island of Oahu on 7 Dec took most of the headlines, but Canadians were already involved in the Pacific theatre, having sent soldiers to Hong Kong just before the conflict began. Britain had first thought of Japan as a threat with the ending of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance in the early 1920s, a threat which increased with the expansion of the Sino-Japanese War. On 21 October 1938 the Japanese occupied Canton (Guangzhou) and Hong Kong was effectively surrounded. Various British Defence studies had already concluded that Hong Kong would be extremely hard to defend in the event of a Japanese attack, but in the mid-1930s, work had begun on new defences. Although Winston Churchill and his army chiefs initially decided against sending more troops to the colony, they reversed their decision in September 1941 in the belief that additional reinforcements would provide a military deterrent against the Japanese.

In the fall of 1941, the British government accepted an offer by the Canadian Government to send two infantry battalions and a brigade headquarters (1,975 personnel) to reinforce the Hong Kong garrison. The Canadian battalions were the Royal Rifles of Canada from Quebec and the Winnipeg Grenadiers from Manitoba. Men were recruited for the Royal Rifles of Canada from the Bay of Chaleur area of New Brunswick in 1941.

The Royal Rifles were serving in New Brunswick where they recruited a large number of soldiers from across the province as well as from PEI and Nova Scotia. In the fall of 1941 these soldiers were deployed to Gander, Newfoundland, where they served on Coastal Defence duties. From there they redeployed to Valcartier where they were outfitted for tropical operations. They travelled by train to the port of Vancouver where they joined up with the Winnipeg Grenadiers. These two units were formed into a formation designated as “C Force” and on 27 October they embarked on board the troopship Awatea and the armed merchant cruiser Prince Robert. They arrived in Hong Kong on 16 November 1941, but without all of their equipment as a ship carrying their vehicles was diverted to Manila at the outbreak of war.

The Royal Rifles had served only in Newfoundland and New Brunswick prior to their duty in Hong Kong, and the Winnipeg Grenadiers had been serving in Jamaica. As a result, many of these Canadian soldiers did not have much field experience before arriving in Hong Kong. Unfortunately, these were the soldiers who found themselves engaged in the Battle of Hong Kong which began on 8 December 1941 and ended on 25 December 1941 with the surrender of the Crown colony to the Empire of Japan. More than 100 casualties suffered by the Royal Rifles during this battle were soldiers recruited from New Brunswick.

The Japanese attack began shortly after 08:00 on 8 December 1941 less than eight hours after the Attack on Pearl Harbor. British, Canadian and Indian forces, commanded by Major-General Christopher Maltby supported by the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps resisted the Japanese invasion by the Japanese 21st, 23rd and the 38th Regiments, commanded by Lieutenant General Takashi Sakai. Some 52,000 Japanese assaulted the 14.000 Hong Kong defenders, most of whom lacked the recent combat experience of their opponents.

The colony had no significant air defences. The Commonwealth forces decided against holding the Sham Chun River which separated Hong Kong from the mainland and instead established three battalions in a defence position known as the Gin Drinkers’ Line across the hills. The Japanese 38th Infantry under the command of Major General Takaishi Sakai quickly forded the Sham Chun River by using temporary bridges. Early on 10 December 1941 the 228th Infantry Regiment, commanded by Colonel Teihichi, of the 38th Division attacked the Commonwealth defences at the Shing Mun Redoubt defended by the 2nd Battalion Royal Scots. The line was breached in five hours and later that day the Royal Scots also withdrew from Golden Hill. D company of the Royal Scots counter-attacked and captured Golden Hill. By 10:00am the hill was again taken by the Japanese. This made the situation on the New Territories and Kowloon untenable and the evacuation from them began on 11 December 1941 under aerial bombardment and artillery barrage. Where possible, military and harbour facilities were demolished before the withdrawal. By 13 December, the 5/7 Rajputs of the British Indian Army, the last Commonwealth troops on the mainland had retreated to Hong Kong Island.

MGen Maltby organised the defence of the island, splitting it between an East Brigade and a West Brigade. On 15 December, the Japanese began systematic bombardment of the island’s North Shore. Two demands for surrender were made on 13 December and 17 December. When these were rejected, Japanese forces crossed the harbour on the evening of 18 December and landed on the island’s North-East. That night, approximately 20 gunners were massacred at the Sai Wan Battery after they had surrendered. There was a further massacre of prisoners, this time of medical staff, in the Salesian Mission on Chai Wan Road. In both cases, a few men survived to tell the story.

On the morning of 19 December fierce fighting continued on Hong Kong Island as the Japanese annihilated the headquarters of West Brigade. A British counter-attack could not force them from the Wong Nai Chung Gap that secured the passage between the north coast at Causeway Bay and the secluded southern parts of the island. From 20 December, the island became split in two with the British Commonwealth forces still holding out around the Stanley peninsula and in the West of the island. At the same time, water supplies started to run short as the Japanese captured the island’s reservoirs.

(Hong Kong Archives Photo)

228th Japanese Infantry Regiment enters Hong Kong, 8 December 1941.

On the morning of 25 December, Japanese soldiers entered the British field hospital at St. Stephen’s College, and tortured and killed a large number of injured soldiers, along with the medical staff. By the afternoon of 25 December 1941, it was clear that further resistance would be futile and British colonial officials headed by the Governor of Hong Kong, Sir Mark Aitchison Young, surrendered. The garrison had held out for 17 days.

The Allied dead from the campaign, including British, Canadian and Indian soldiers, were eventually interred at the Sai Wan Military Cemetery and Stanley Military Cemetery. A total of 1,528 soldiers, mainly Commonwealth, are buried there. At the end of February 1942, The Japanese government stated that numbers of prisoners of war in Hong Kong were: British 5,072, Canadian 1,689, Indian 3,829, others 357, for a total of 10,947. Of the Canadians captured during the battle, 267 subsequently perished in Japanese prisoner of war camps.

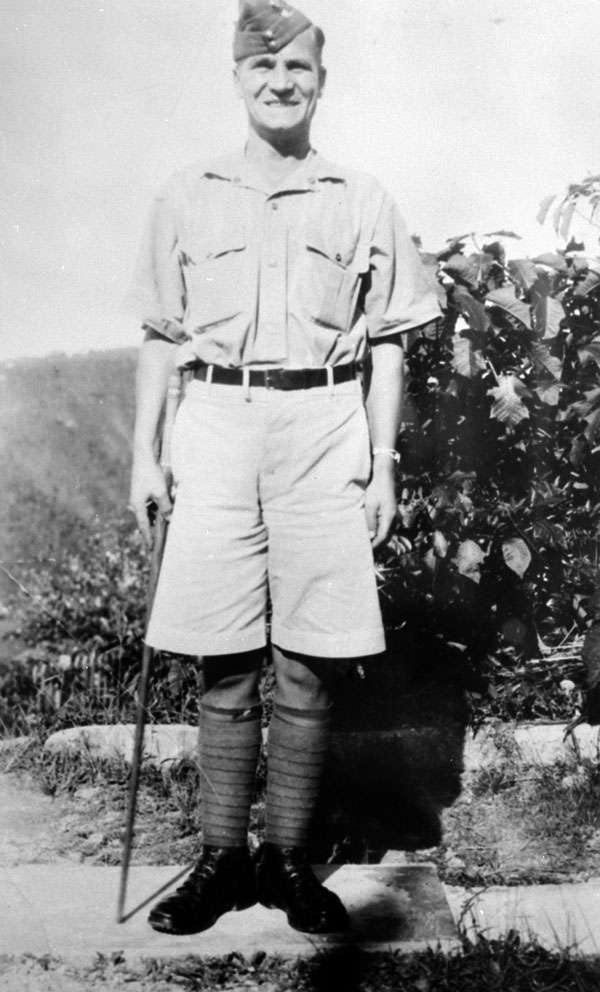

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3225429)

Company Sergeant-Major J.R. Osborn of “A” Company, The Winnipeg Grenadiers, Jamaica, ca. 1940-1941. Killed in action at Hong Kong on 19 December 1941, CSM Osborn was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross.

Following the battle, John Robert Osborn was awarded the Victoria Cross. After seeing a Japanese grenade roll in through the doorway of the building Osborn and his fellow Canadian Winnipeg Grenadiers had been garrisoning, he took off his helmet and threw himself on the grenade, saving the lives of over 10 other Canadian soldiers.[1]

Canada responded to the outbreak of war with Japan by significantly strengthening its Pacific coastal defences, ultimately stationing more than 30,000 troops, 14 RCAF squadrons, and over 20 warships in British Columbia. Canadian forces also co-operated with the United States in clearing the Japanese from the Aleutian Islands off Alaska. Before Japan surrendered in August 1945, a Canadian cruiser, HMCS Uganda, participated in Pacific naval operations, two RCAF transport squadrons flew supplies in India and Burma, and communications specialists served in Australia.

[1] Internet: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Hong_Kong.

The fighting was over, but the killing was not. The horror of Japanese occupation and captivity was only beginning for the defeated at Hong Kong. In St. Stephen’s Hospital in Stanley, the Japanese bayoneted 70 Allied soldiers in their beds and brutally raped the nurses there, many of them to death. It was only one example of numerous savage atrocities committed by Japanese troops against soldiers and civilians alike after the surrender.

The Canadians had suffered badly: 783 men and 59 officers killed or wounded in the battle. Another 195 would die in the miserable conditions behind Japanese wire. Altogether, of the 1,975 Canadians who were sent to Hong Kong 555 would not return, including the Grenadiers’ commanding officer, Lt. Col. Sutcliffe, who died as a POW. Many of those who did make it home were broken in body and spirit for the rest of their lives, which were often shorter than what they would have been because of the years of malnourishment, overwork, and disease. (Jerome M. Baldwin)

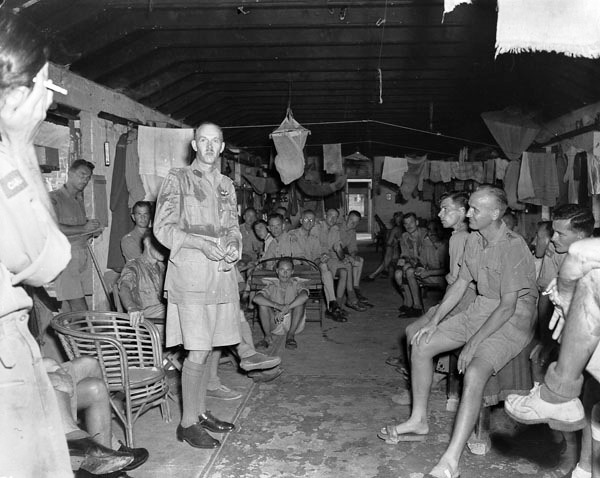

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, PA-193015)

Commander Peter MacRitchie of HMCS Prince Robert meeting with liberated Canadian prisoners-of-war at Shamshuipo Camp, Hong Kong, August 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3396566)

Landing party disembarking from HMCS Prince Robert during the liberation of Hong Kong, ca. 30 August 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3396566)

Canadian and British prisoners-of-war liberated by the landing party from HMCS Prince Robert, Hong Kong, ca. 30 August 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3227634)

An unidentified Canadian officer (possibly Colonel McKenna) being helped aboard HMCS Prince Robert, Hong Kong, 29 September 1945.

(Author Photos)

Hong Kong War Memorial, Ottawa.

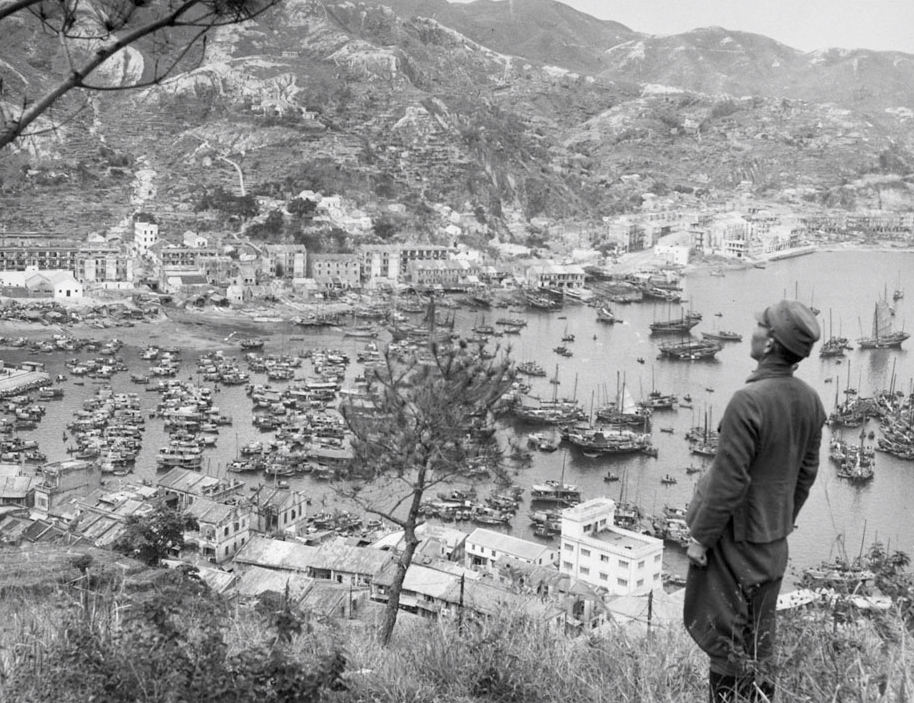

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3997716)

Sau Ki Wan where the Tanaka Butai landed the night of 18-19 December 1941 – Figure in foreground is Tanaka himself, taken 19 March 1947 from Lye Mun Barracks, Sai Wan Hill.