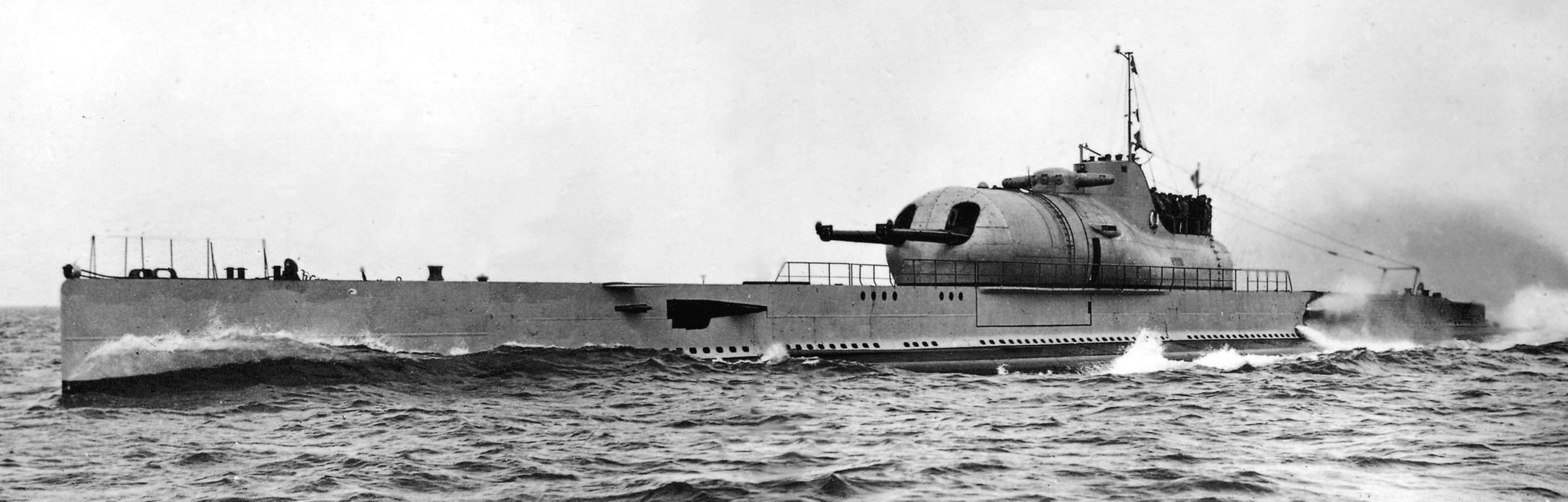

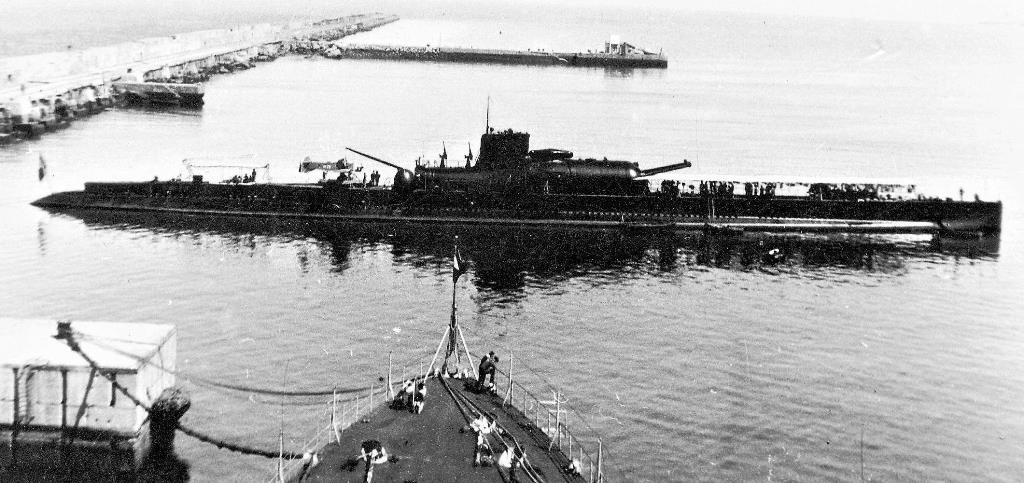

French Cruiser Submarine FS Surcouf (NN-3), lost 18 Feb 1942

(Marine nationale, Ministère de la Défense Photo)

The French croiseur sous-marin (cruiser submarine) FS Surcouf (NN-3), served in both the French Navy and the Free French Naval Forces during the Second World War.

At 10.30pm on 18 February 1942, the Surcouf was lost with all hands in the Caribbean Sea. An official joint U.S. and Free French report stated that she left Bermuda on 12 February and was accidentally rammed and sunk by the American freighter Thompson Lykes off the north coast of Panama near the Panama Canal. The report states that the accident was due to both vessels running at night without lights because of the menace of German U-boats.

Steve MacGregor has assembled a number of conflicting pieces of data found on the sinking of the Surcouf. I have reviewed an additional number of stories from the Internet to build this general narrative. In light of the personal reports of the Captain and crew of the Thompson Lykes, it seems their collision with the Surcouf is the most reasonable explanation of her loss. Although her wreck has yet to be discovered, there are quite a few less compelling alternative stories of her fate.

YouTube video – Surcouf: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yGe5lA9se_8

Approximate location of the collision of the Thompson Sykes and the Surcouf on 18 Feb 1942.

It is possible the collision had damaged Surcouf ‘s radio and the stricken boat limped towards Panama hoping for the best. The records of the USAAF 6th Heavy Bomber Group operating out of Panama show them sinking a large submarine northeast of Columbus on the morning of 19 February 1941. Two Northrup A-17 and one Douglas B-18 Bolo aircraft were involved, dropping eight bombs on the vessel. Since no German submarine was lost in the area on that date, it could have been Surcouf. A later French investigation commission stated that the Surcouf had been sunk by US planes in the morning of the 18th in a “friendly fire” accident in the same area.

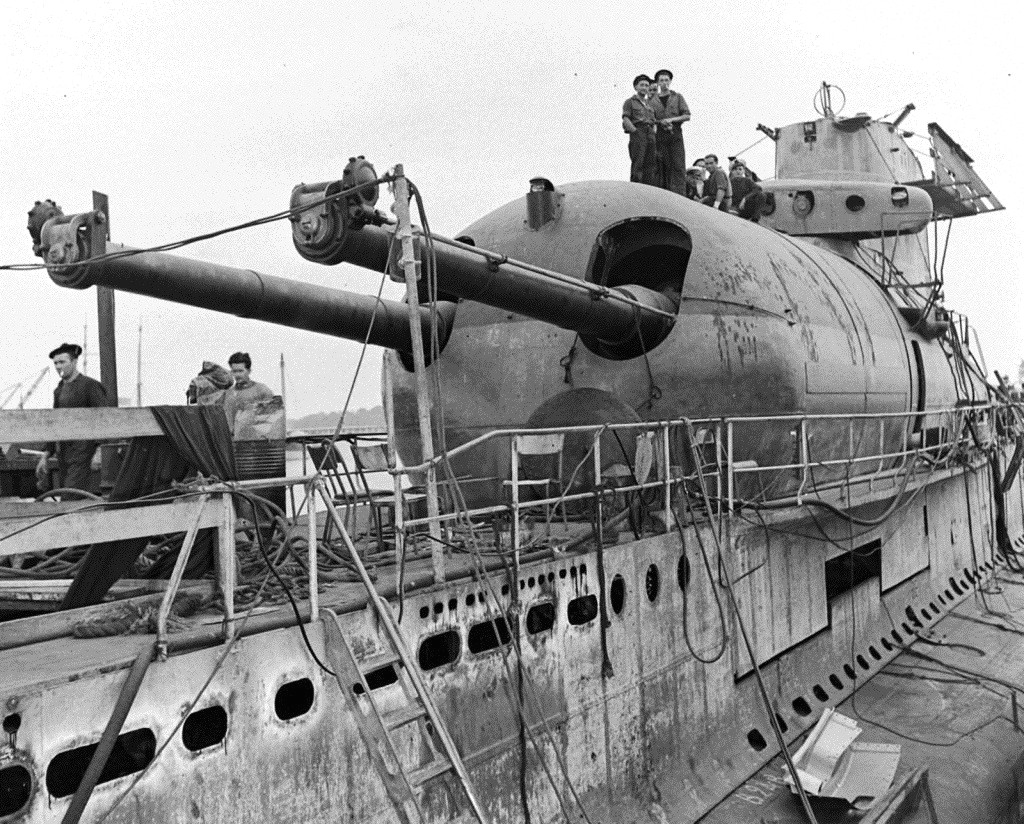

(Marine nationale, Ministère de la Défense Photo)

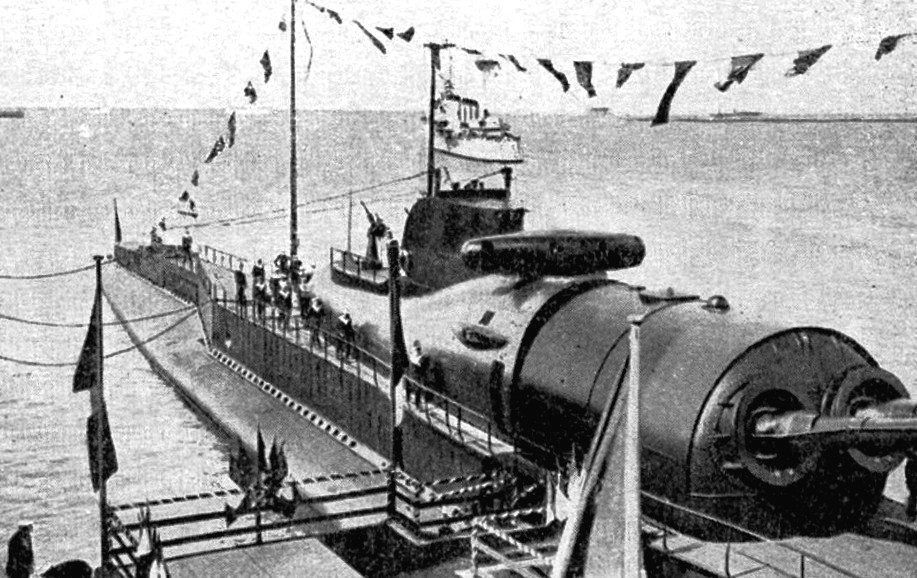

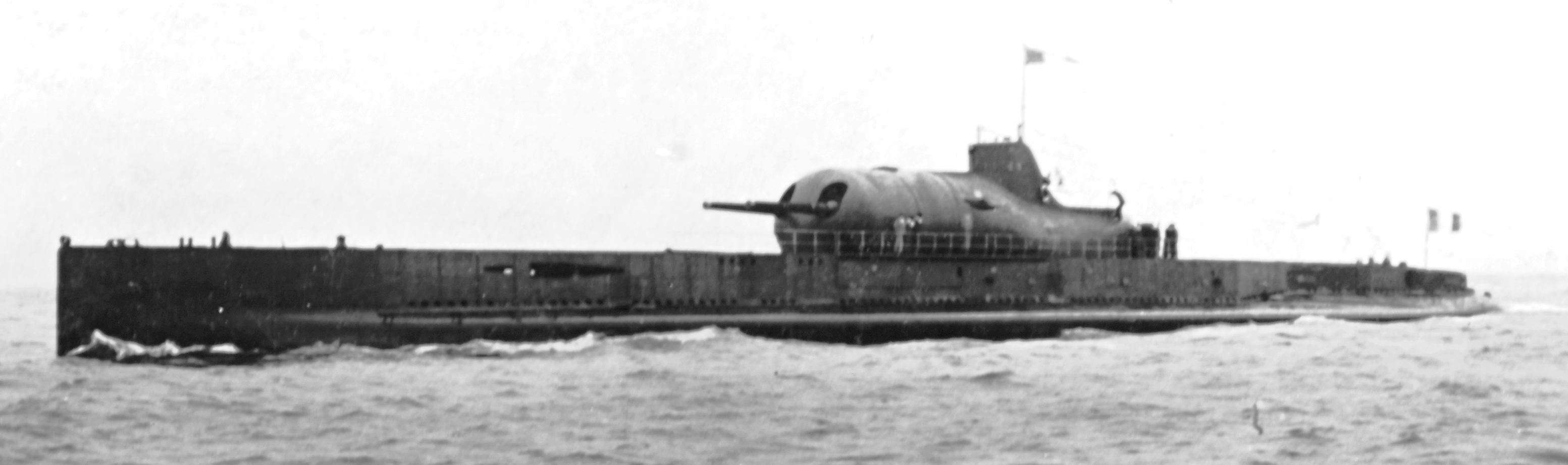

The Surcouf was named after Robert Surcouf, who had been a French privateer. At the time of her launch in 1929, she was the world’s largest pre-Second World War submarine, 361 feet long, and weighed 3,304 tons. She was powered by a pair of 3800-hp Sulze diesel engines and two electric motors and had a range of 10,000 miles at 10 knots. She could reach as surface speed of 18 knots, 8.5 knots submerged.

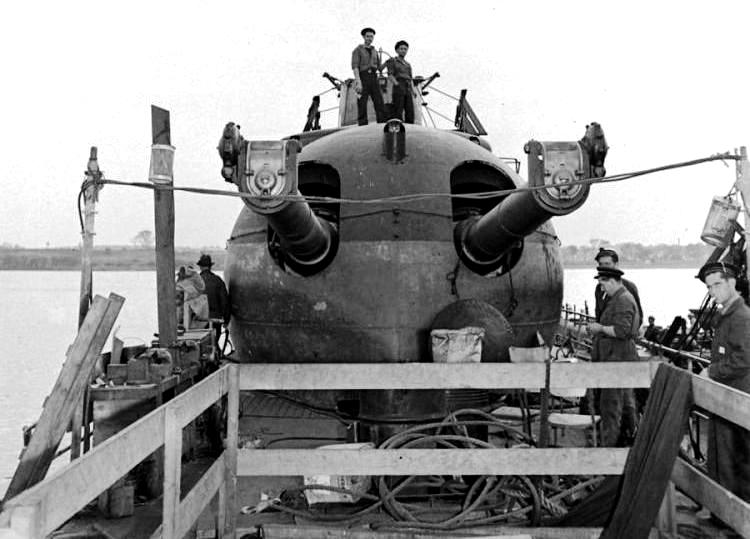

(Marine nationale, Ministère de la Défense Photo)

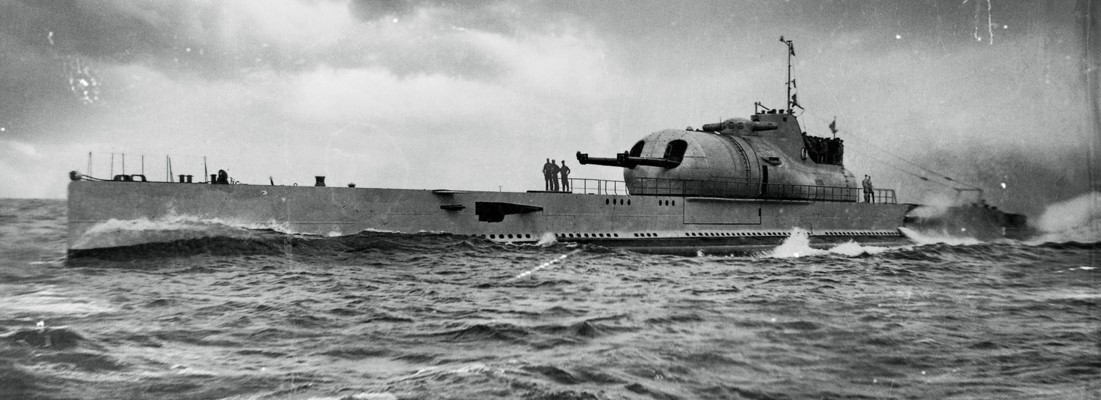

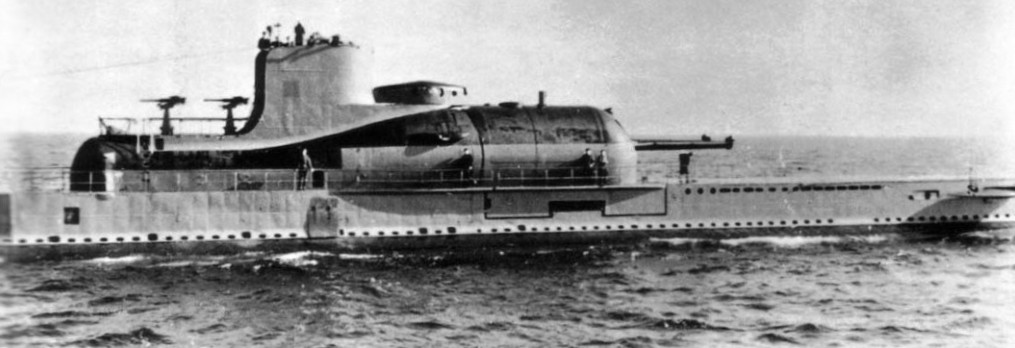

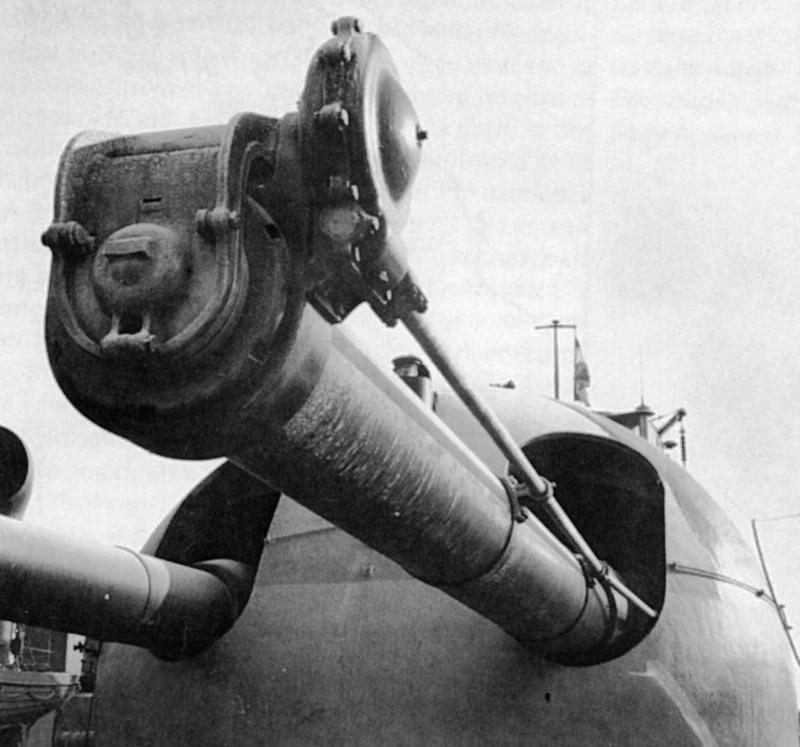

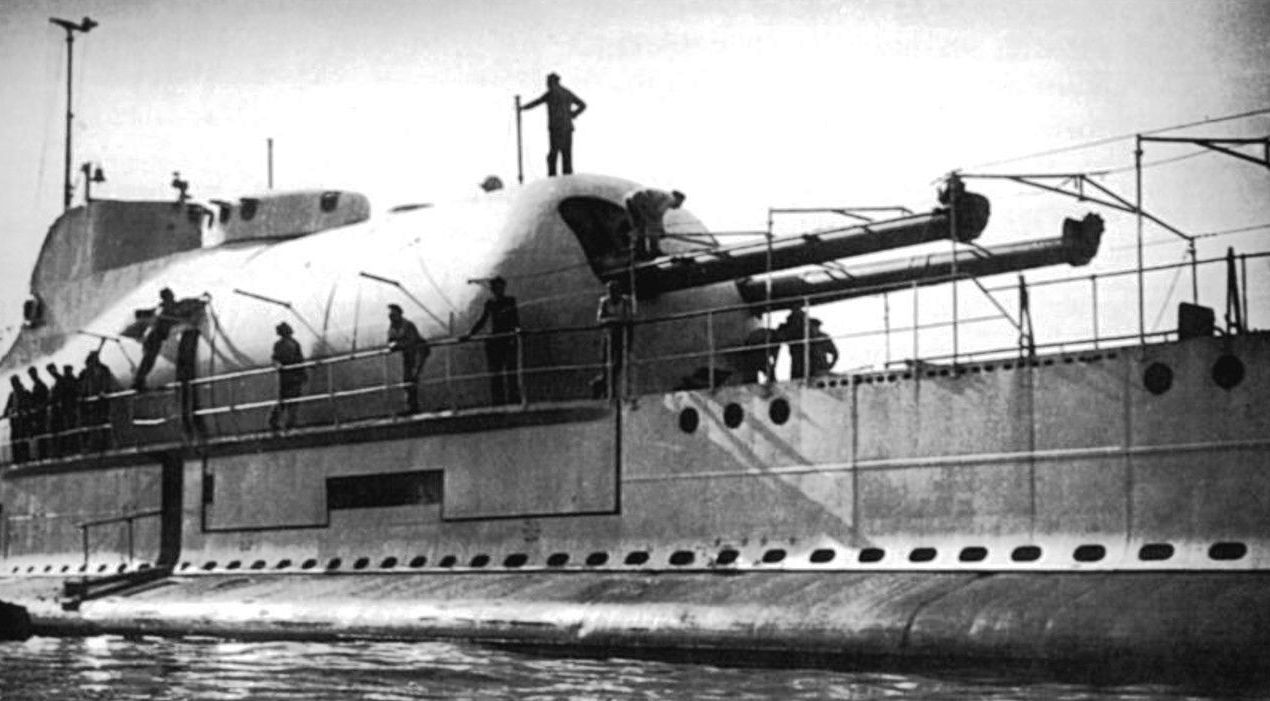

Surcouf‘s 203-mm/50 (8-inch) guns mounted in a Twin Turret M1929, with muzzle closing mechanisms to keep water out of the barrels.

(Marine nationale, Ministère de la Défense Photo)

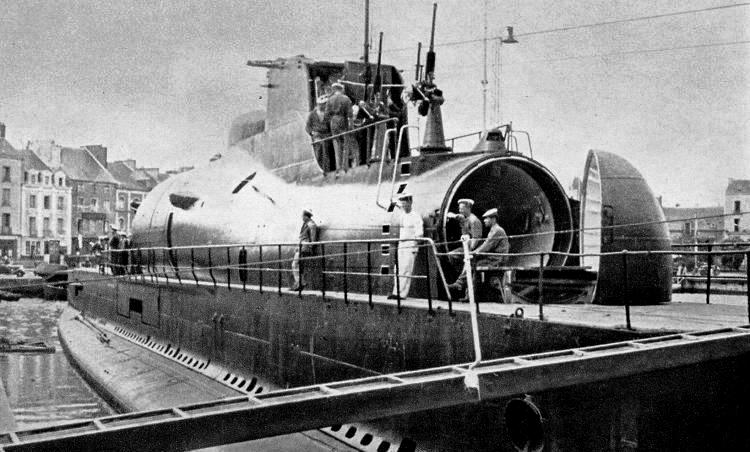

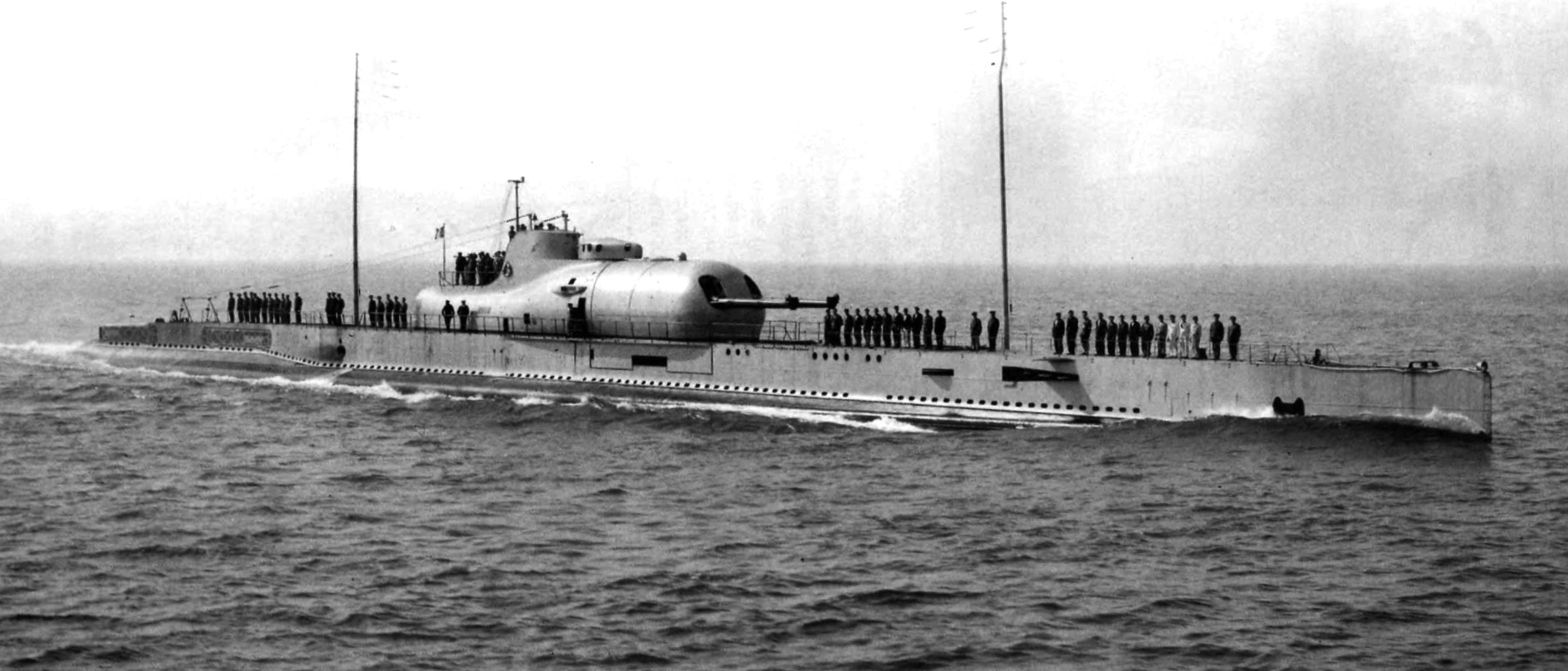

Surcouf starboard view with details of the 203-mm/50 (8-inch) guns mounted in a Twin Turret M1929.

The Surcouf was designed to be an underwater heavy cruiser, that would seen and engage in surface combat. She was armed with twin 203-mm/50 Modèle 1924 (8-inch) guns mounted in a single pressure-tight turret forward of the conning tower. These guns were the same calibre as that of a surface heavy cruiser, a formidable armament for a submarine.

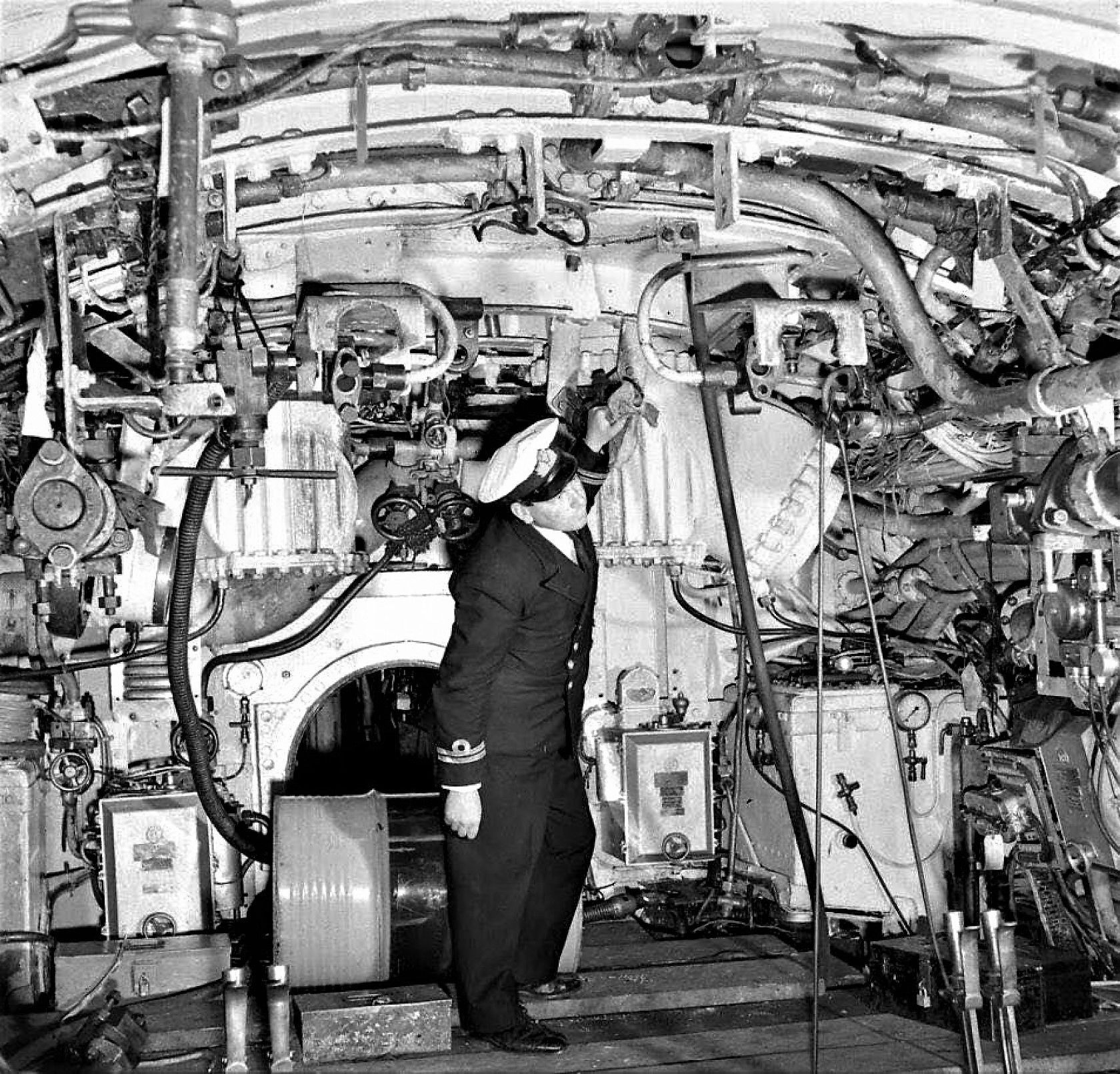

(Marine nationale, Ministère de la Défense Photo)

(LIFE magazine Photo)

She was provisioned with 600 rounds of ammunition. The two guns had a 60-round magazine capacity and were controlled by a director with a 5-m (16 ft) rangefinder, mounted high enough to have an 11 km (5.9 nmi/6.8 mi) view of the horizon. The Surcouf ’s crew was capable of putting the guns into action and firing within three minutes after surfacing. Using the boat’s periscopes to direct the fire of the main guns, Surcouf could increase this range to 16 km (8.6 nmi/9.9 mi). An elevating platform was originally supposed to lift lookouts 15 m (49 ft) high, but this design was abandoned quickly because of roll. Two 37-mm Hotchkiss Anti-aircraft cannon and machine guns were mounted on the top of the hangar.

(Marine nationale, Ministère de la Défense Photo)

Inside the Control Room of Surcouf.

(Marine nationale, Ministère de la Défense Photo)

Inside the Control Room of Surcouf.

(Marine nationale, Ministère de la Défense Photo)

Surcouf visiting Casablanca, Morocco, in 1938.

The boat encountered several technical challenges, owing to the 203-mm guns. Because of the low height of the rangefinder above the water surface, the practical range of fire was 12,000 m (13,000 yd) with the rangefinder (16,000 m (17,000 yd) with sighting aided by periscope), well below the normal maximum of 26,000 m (28,000 yd). The duration between the surface order and the first firing round was 3 minutes and 35 seconds. This duration could have been longer in case the boat was going to fire broadside, which meant surfacing and training the turret in the desired direction. Firing had to occur at a precise moment of pitch and roll when the ship was level. Training the turret to either side was limited to when the ship rolled 8° or more. The Surcouf was not equipped to fire at night, due to inability to observe the fall of shot in the dark. The mounts were designed to fire 14 rounds from each gun before their magazines were reloaded.

(Marine nationale, Ministère de la Défense Photo)

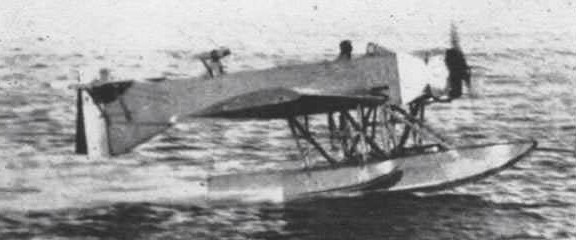

She was built with a cylindrical watertight hangar located behind the conning tower, housing a Marcel Besson MB.411-AFN reconnaissance floatplane. This aircraft was stored in ‘kit form’ and it could be rolled out and launched from a ramp. The floatplane was primarily used for gun calibration and was capable of a speed of 100 knots with a range of 400 kilometres. The Besson observation plane could be used to direct fire out to the guns’ 26 mi (23 nmi; 42 km) maximum range.

MB.411. The French Navy required a spotter aircraft for its new submarine Surcouf, and ordered a production version, designated MB.411. It was specifically designed for housing in a cylindrical hangar in the back of Surcouf’s conning tower. The Besson MB.411 could be assembled to put on the wings in about 4 minutes (at open sea up to 20 minutes) after it was removed from its hangar, then lowered to the water and retrieved by a crane. MB.411 was a low-wing monoplane with a large single central float and under the wing two small stabilizing floats. The Besson MB.411 was constructed with a mix of wood and metal, with canvas covering. In autumn of 1934, the MB.411 was sent to Brest for boarding trials on the Surcouf. The aircraft made its first flight at Le Mureau in June 1935. Surcouf then took the Besson MB.411 to the Caribbean arriving in September 1935 for sea trials. In January 1936 MB.411 returned to Mureaux for changes. The second MB.411 was completed in February 1937. The second MB.411 made its first flight December 1937 and was delivered July 1938. The second MB.411 replaced the first in the Surcouf.

On 18 June 1940 the Surcouf chose to join the Free French Naval Forces in England. The Surcouf was assigned to the protection of convoys in the Atlantic near Bermuda, but the MB.411 stayed in England. It made a few flights on the coast of Devon and was damaged in Plymouth in April 1941 during a Luftwaffe bombing raid. Apparently, it was later repaired, changing its appearance, and used by 765 Naval Air Squadron (765 NAS) from RNAS Sandbanks. Later scrapped at RAF Mount Batten after being rendered unserviceable due to lack of spares. The first MB.411 remained in France and was assigned to Fleet Squadron Aeronavale Escadrille 7-S-4 in St Mandrier and was scrapped in France. (Sharpe, Michael. Biplanes, Triplanes, and Seaplanes. (London: Friedman/Fairfax Books., 2000).

The Surcouf’s underwater armament included ten torpedo tubes with four 550-mm (22-inch) torpedo tubes in the bow and two swiveling external launchers in the rear superstructure, each equipped with one 550-mm and two 400-mm (14-inch) torpedo tubes. The Surcouf carried eight 550-mm and four 400-mm reloads. es and another 8 X 400-mm torpedoes.

The Surcouf also carried a 4.5 m (14 ft 9 in) motorboat and contained a cargo compartment with fittings to restrain 40 prisoners or lodge 40 passengers. The submarine’s fuel tanks were very large; enough fuel for a 10,000 nmi (19,000 km; 12,000 mi) range and supplies for 90-day patrols could be carried.

The Surcouf ’s maximum safe diving depth was 80 metres; however, the boat was capable of diving to 110 meters without notable deformations to its thick hull, with a normal operating depth of 178 m (584 ft). Crush depth was calculated at 491 m (1,611 ft).

(Marine nationale, Ministère de la Défense Photo)

(Marine nationale, Ministère de la Défense Photo)

The Surcouf was unreliable and suffered from several crucial design defects. She was prone to leaks, particularly within the gun turret, and which seriously affected the trim of the craft when submerged. On more than one occasion, the Surcouf dived uncontrollably well below her specified maximum depth of 80 metres but where safe operation was resumed without loss.

Her diesel engines, electric motors and other systems often broke down and spare parts were almost impossible to obtain due to her unique design. In some cases, the problems were an inherent part of the design and could not be resolved. The additional weight and wind-shear above the deck caused the vessel to roll badly even in a modest swell, making it nearly impossible to assemble and launch the aircraft in all but dead calm conditions. During stormy weather, acid was apt to spill from her batteries. Diving meant securing twenty-four vents and typically took about two and half minutes to complete during which time she was vulnerable to aerial attack. In an age of rapidly developing aircraft with greater capability and range, there were doubts whether Surcouf and other vessels of this design could ever operate safely in areas where land-based aircraft could reach. Overall, Surcouf was far less than the planners had envisaged, and future development of the design was cancelled. Surcouf would remain as a sole member of her class.

(IWM Photo)

General Charles de Gualle departing the Surcouf, after exiting from the open hangar door. He and Admiral Muselier visited ships manned by Free French forces in a British port, 1940.

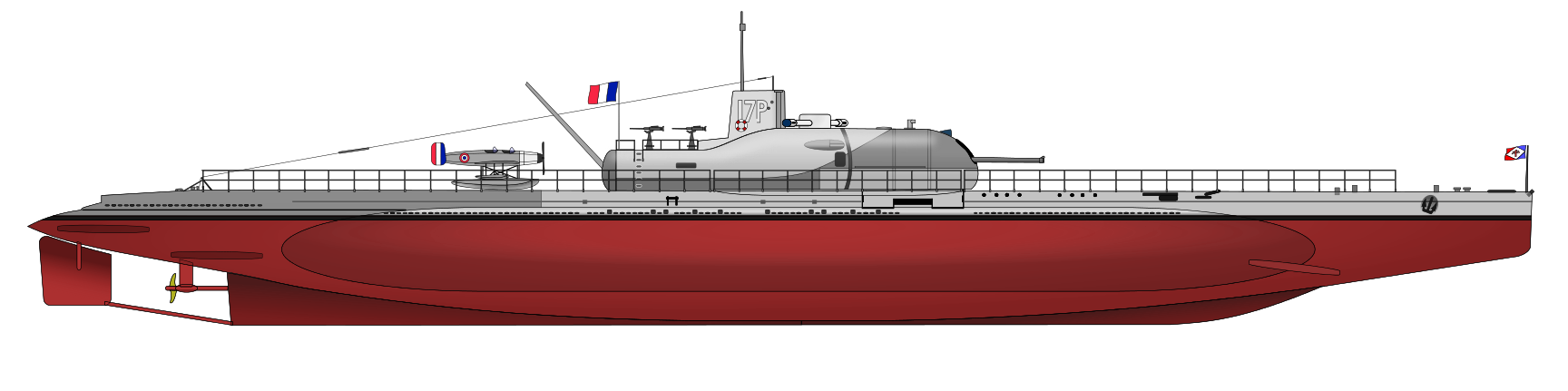

(Rama artwork)

1940 configuration, with two-tone gray paint and 17P identification number on the conning tower.

From the beginning of the Surcouf ‘s career until 1932, the boat was painted of the same grey colour as surface warships, then in Prussian dark blue, a colour which was conserved until the end of 1940 where the boat was repainted with two tones of grey, serving as camouflage on the hull and conning tower.

The Surcouf’s first commanding officer was Capitaine de Frégate (Frigate Captain/Commander) Raymond de Belot. His missions included ensuring contact with the French colonies; working in concert with French naval squadrons to search and destroy enemy fleets, and to pursue enemy convoys.

In 1940, Surcouf was based in Cherbourg, but in May, when the Germans invaded, she was being refitted in Brest following a mission in the Antilles and the Gulf of Guinea. Under command of Frigate Captain Martin, unable to dive and with only one engine functioning and a jammed rudder, she limped across the English Channel and sought refuge in Plymouth.

On 3 July 1940, the British, concerned that the French Fleet would be taken over by the German Kriegsmarine at the French armistice, executed Operation Catapult. The Royal Navy blockaded the harbours where French warships were anchored and delivered an ultimatum: rejoin the fight against Germany, be put out of reach of the Germans, or scuttle. Few accepted willingly; the North African fleet at Mers-el-Kebir and the ships based at Dakar (West Africa) refused. The French battleships in North Africa were eventually attacked and all but one sunk at their moorings by the Mediterranean Fleet.

French ships lying at ports in Britain and Canada were also boarded by armed marines, sailors and soldiers, but the only serious incident took place at Plymouth aboard Surcouf on 3 July, when two Royal Navy submarine officers, Cdr Denis ‘Lofty’ Sprague, captain of HMS Thames and Lt Patrick Griffiths of HMS Rorqual and French warrant officer mechanic Yves Daniel were fatally wounded, and a British seaman, Albert Webb, was shot dead by the submarine’s doctor.

(Marine nationale, Ministère de la Défense Photo)

Surcouf, turret forward, guns elevated.

(Marine nationale, Ministère de la Défense Photo)

Surcouf, turret forward, guns trained off the centerline, illustrating how a portion of the superstructure rotated with the gunhouse.

(Marine nationale, Ministère de la Défense Photo)

By August 1940, the British completed Surcouf ‘s refit and turned her over to the Forces Navales Françaises Libres, FNFL (Free French Navy) for convoy patrol. The only officer not repatriated from the original crew, Capitaine de frégate Georges Louis Blaison, became the new commanding officer on 7 October 1941. Because of Anglo-French tensions about the submarine, accusations were made by each side that the other was spying for Vichy France; the British also claimed Surcouf was attacking British ships. Later, a British officer and two sailors were put aboard for “liaison” purposes. One real drawback was she required a crew of 110 – 130 men, which represented three crews of more conventional submarines. This led to the Royal Navy’s reluctance to recommission her.

(Marine nationale, Ministère de la Défense Photo)

The MB.411 was a very compact monoplane with a large central float and two small outriggers under the wings. In order to reduce the hangar requirements she had an unusual tail with the larger part of the vertical rudder mounted below the fuselage instead of above it.

(Marine nationale, Ministère de la Défense Photo)

Unloading Surcouf’s Besson floatplane from its hangar.

Apparently the Besson floatplane was taken ashore while Surcouf was docked in Britain and moved to a nearby dock shed for service. The Besson aircraft was destroyed there during a bombing raid and could not be replaced. For much of its later career, Surcouf sailed without the aircraft aboard and with an empty hangar that was a liability rather than an asset.

(Marine nationale, Ministère de la Défense Photo)

View of the Surcouf’s aircraft hangar open and the submarine’s anti-aircraft guns elevated vertically, 1936.

(IWM Photo, A 2589)

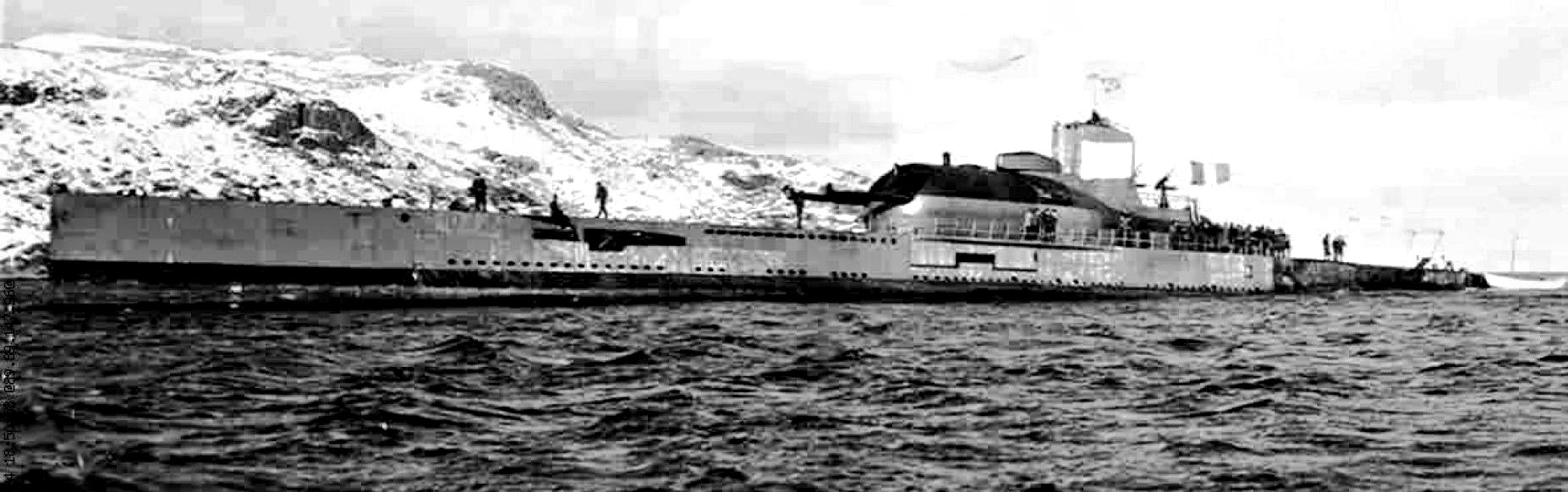

Surcouf heading towards Halifax, Feb 1941.

(Marine nationale, Ministère de la Défense Photo)

Surcouf heading towards Halifax, Feb 1941.

Surcouf then went to the Canadian base at Halifax, Nova Scotia and escorted trans-Atlantic convoys. In April 1941, she was damaged by a German plane at Devonport. On 28 July, Surcouf went to the United States Naval Shipyard at Portsmouth, New Hampshire for a three-month refit.

(Marine nationale, Ministère de la Défense Photo)

Surcouf in dry dock, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, September 1941.

After leaving the shipyard, Surcouf went to New London, Connecticut, perhaps to receive additional training for her crew. Surcouf left New London on 27 November to return to Halifax.

In December 1941, Surcouf carried the Free French Admiral Emile Muselier to Canada, putting into Quebec City. While the Admiral was in Ottawa, the Surcouf sailed to Halifax, where, on 20 December, they joined Free French Escorteurs, the corvettes Mimosa, Aconit and Alysse, and on 24 December, took control of the islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon (south of Newfoundland) for Free France without resistance.

(Marine nationale, Ministère de la Défense Photo)

(Marine nationale, Ministère de la Défense Photo)

In January 1942, the Free French leadership decided to send Surcouf to the Pacific theatre, after she had been re-supplied at the Royal Naval Dockyard in Bermuda. However, her movement south triggered rumours that Surcouf was going to liberate Martinique from the Vichy regime. In fact, Surcouf was bound for Sydney, Australia, via Tahiti. She departed Halifax on 2 February for Bermuda, which she left on 12 February, bound for the Panama Canal.

(Marine nationale, Ministère de la Défense Photo)

The Surcouf vanished on the night of 18/19 February 1942, about 130 km (70 nmi/80 mi) north of Cristóbal, Colón, while en route for Tahiti, via the Panama Canal. An American report concluded the disappearance was due to an accidental collision with the American freighter Thompson Lykes, steaming alone from Guantanamo Bay, on what was a very dark night. The freighter reported hitting and running down a partially submerged object which scraped along her side and keel. Her lookouts heard people in the water, but the freighter did not stop, thinking she had hit a U-boat, though cries for help were heard in English. A signal was sent to Panama describing the incident.

According to an article by Alan Donaldson, what precisely happened to the Surcouf on that last fatal voyage has remained conjecture ever since. Speculation about sabotage or mutiny was rife at the time but failed to hold up under scrutiny. It seems far more probable, though equally unproven, that she was the victim of a night-time collision with the freighter Thompson Lykes.

Thompson Lykes C1-B breakbulk general cargo freighter, built by the Bethlehem Steel Co, Sparrows Point, Maryland, 1941, US Maritime Commission No. 81; yard hull No. 4346, delivered 25 Apr 1941. She was involved in a collision in the Caribbean on 18 Feb 1942 with what may have been the French submarine Surcouf, which was lost about that time and place. She is shown here in 1954 ferrying Republic F-84F Thunderstreak jets on her deck. Thompson Lykes was scrapped in 1973.

At 4.40pm, the previous day, the 6,829-ton Thompson Lykes with a crew of 43, departed from the Cristobal exit of the Panama Canal and headed for Cuba. She was 418 feet long and 60 feet wide, with a fully loaded draft of 28 feet. Powered by steam turbines, with a single screw, she had 4,000 shp and make 14 knots. On this voyage, she was lightly loaded and drawing 11 feet forward and 27 feet aft. Soon after leaving port, her master, Henry Johnston ordered full speed and the vessel surged ahead at fifteen knots on a heading of 028°.

The ship was just ten months old and owned by the Lykes Brothers Steamship Company of New Orleans. In the wake of Pearl Harbour, the ship had been time-charted by the US Army and was regularly employed to ferry Army cargo. Johnston had been captain of the ship since it was new and the mate, Andrew Thompson, was a very experienced seaman. Most of the crew, by contrast, were conscripts from the US Army 58th Coast Artillery Transport Detachment and many had never been to sea before and because many of the former crew had been drafted into the US Navy.

On 18 Feb 1942, Johnston wisely chose an experienced seaman for duty in the crow’s nest before retiring to his office behind the bridge. As night fell, external lights remained off while internal lights were shielded. America’s war was only ten weeks old but already merchant vessels had been sunk by U-Boats and Johnston was taking no unnecessary risks. By 7pm, the brief Caribbean twilight gave way to complete darkness and sea conditions began to deteriorate. In response, Johnston ordered a speed reduction to thirteen knots. One hour later, with the weather worsening steadily, Johnston elected to steer a more direct route and the vessel turned to a heading of 022°. He had no warning of other vessels in the area and the rule of radio silence meant he was unable to seek updates or advice. At 9pm, the radio operator received a coded message which changed their current mission and ordered the vessel to sail for Cienfuegos instead. The new course on the gyro was 355°.

All remained quiet until 10.28pm when the helmsman, Atwell, suddenly spotted a white light moving up and down on their right side. He immediately reported it to Thompson who ordered full rudder to port. A short time later, the crows nest telephone rang, and the lookout reported seeing a light dead ahead. Thompson, suddenly realising that the unknown vessel was crossing their bows ordered right full rudder, but it was too late. Seconds later, the vessel hit something.

Captain Johnston had rushed back onto the bridge and demanded an explanation but before Thompson could reply, there was a loud explosion and a brilliant momentary flare illuminating both sides of the bow. As the flames died away, Private Dohrman Henke, had a fleeting glance of something white in the water and several crewmen heard people calling for help. Johnston and Thompson, blinded by the sudden light, saw nothing and asked Henke what he had seen. The private replied that he thought they had hit a sub and that it had passed down their port side.

Thompson was sent forward with an inspection crew to check the condition of the bow while Johnston ordered a slow turnaround back to the point of impact. Despite the obvious risks, the searchlight was switched on and crewmen lined the rails with orders to look for survivors and/or wreckage. Thompson returned to the bridge and reported that the damage to the bow of the ship was less than first feared and did not threaten the safety of the ship. This news allowed the search to continue and the Thompson Lykes criss-crossed the area several times in search of survivors, but none were found.

Neither survivors, bodies nor wreckage was found, only a large heavy fuel oil slick. This lack of debris naturally caused the crew to wonder what it was they had hit. They felt certain that it was a vessel of some kind and the helmsman believed that it must have been low in the water else he’d have seen it against the horizon. A few crew members had momentarily seen a long cylindrical shaped object run down the port side of the ship which, when taken together with the above, suggested they had struck a submarine on the surface. Since they had not been notified of friendly vessels in the area, they assumed that the unknown craft was probably a surfaced German U-Boat engaged in recharging her batteries. Captain Johnston broke radio silence and reported the incident to the naval authorities at Cristobal. In reply, the Thompson Lykes was ordered to remain in the vicinity and continue the search.

There is a lot of speculation about what actually happened to the Surcouf that night. The Captain and crew of the Thompson Lykes were certainly convinced that their ship had collided with a submarine. On 19 February 1942, the British Consular Shipping Adviser at Colón, Panama sent the following message to the Admiralty:

French Cruiser-Sub SURCOUF not repeat not arrived. THOMPSON LYKES USA Army Transport northbound convoy yesterday now returned after collision with unidentified vessel which apparently sank at once at 2230R 18th February in latitude 010 degs 40 north longitude 079 degs 30 West. She searched the vicinity until 0830 today 19th February but no survivors or wreckage. Only sign was oil. Considerable bow damage made to THOMPSON LYKES at fore foot.

Three days later this was followed by a second message from the British Consular Shipping Adviser at Colón after he had read statements from the crew of the Thompson Lykes and personally examined the damage to the freighter:

(a) United States Ship without lights course 356 degrees at full speed approximately 14 knots. Originally steering for Windward passage but diverted for Cienfuegos, Cuba.

(b) Other vessel not observed until white light flash seen one point to starboard bow about half minute before collision. Wheel put hard to port but before ship answered helm light again seen this time right ahead so wheel reversed hard to starboard engine still full ahead.

(c) Heavy collision very shortly afterwards. On reaching bridge after collision Master stopped engine. While still close on port beam vessel seen sinking with great disturbance of water. Gunner states bow of other vessel thrown up clear of the water before sinking. Calls in English for help were heard by witnesses but their ship carried headway lost contact. Master delayed lowering lifeboats allegedly on account of sea running intending to do so later when party of survivors were located.

(d) Meanwhile shortly after vessel sank violent underwater explosion was felt in United States ship. Having carried her way about half mile ship put back to where Master estimated other had sunk. Searchlight revealed no sign of survivors or wreckage but much oil. Weather described as rather heavy sea fresh wind; visibility not mentioned. United States Authorities informed by W/T. Search abandoned 0830, 10 hours later.”

The message also went on to note that the Consular Shipping Adviser did not believe that the collision had been with another surface vessel:

“From personal observations 15 yard distance, nature of damage to US ship points to other not being surface craft, as upper two third stem post and of pole plate not damaged.”

The crew of the Thompson Lykes believed that they had rammed and sunk a U-Boat. U-Boats were certainly operating in the area at the time – on 16th February three U-Boats (U-156, U-67 and U-129) began operations against oil tankers and shore refineries in the Caribbean. However, none of these U-Boats reported damage following a collision and none were lost. Two U-Boats were destroyed in February, one on the 2nd (the U-581) and one on the 6th (the U-82). But both were known to be destroyed by depth charge attacks in the vicinity of the Azores. No British or allied submarines were lost in February 1942 and only one American, the USS Shark which was lost while operating in the Pacific while on a patrol in the Makassar Strait between the islands of Borneo and Sulawesi. If the Thompson Lykes did indeed ram a submarine, Surcouf is the only appropriate vessel known to have been in the general area and subsequently reported lost.

The unfortunate element is that no survivors, bodies or debris were found. The Surcouf would have had crew present on the bridge, and they would have been wearing life-jackets. Even if they were killed during the collision or drowned before they could be rescued, their bodies should have been found. The graphic and dramatic description given by the crew of the Thompson Lykes noted a violent collision followed by an underwater explosion. If this was indeed a badly damaged and sinking submarine, some debris should have been found by the search conducted during the night and at daylight the next day, but nothing was. The relatively light damage to the forefoot of the 6,700 ton Thompson Lykes does not seem significant in view of the reported heavy collision with the 3,300 ton Surcouf. Surveyors from the American Bureau of Shipping (ABS) examined the Thompson Lykes after the incident and issued a report on 25 February 1942. The report noted that the only damage involved several forward frames and plates that had been distorted and a bottom fuel tank holed (which might account for the oil seen on the surface in the area of the collision). ABS recommended that, after temporary repairs, the ship was safe to proceed to New Orleans for further repairs. For the size of the two colliding vessels, this does not seem as serious as one might expect.

At 10.45am next morning, the USS Tatnall arrived and both ships were later joined by the destroyer USS Barry. Despite their best efforts, no wreckage or survivors were found, and the only sign of the collision remained the oil slick. The Thompson Lykes then departed from the area and returned to Cristobal. She arrived there in the mid afternoon of 19 Feb 1942. News that Surcouf was overdue arrived later that day.

Examination of the Thompson Lykes took place shortly afterwards and the American Bureau of Shipping issued their findings on 25 Feb. They reported that several frames and plates had been distorted and a bottom fuel tank holed. They recommended that, after temporary repairs, the ship should be allowed to proceed to New Orleans for repairs. The damage estimate was $38,000.

Over the following seven months, a bitter wrangle arose between the Free French on one side and the British and American governments on the other. The Free French continually doubted the official reports of the loss and despite subsequent and detailed enquiry concluded that since neither vessel had been showing lights, then this had been the cause of the accident. The question remains, “did the Thompson Lykes sink the Surcouf?”

Photographs of the damaged bow of Thompson Lykes show a marked twist to starboard and a dent close to the twelve-foot mark which suggests that this could have been caused by the deck of the other vessel. There is little damage above this mark and, given the known draught at the bow of eleven feet, we can deduce that the free board (the height above the surface of the water) of the other vessel was very low indeed – perhaps only a few feet at most. This tends to support the crews contention that they had indeed, collided with a submarine.

No other vessels were reported as lost in the area which further points towards the Surcouf as being the victim of this collision. The British Naval Liaison Officer (BNLO) reported that officers in the conning tower of Surcouf often used an unshaded light to see the instruments. Could this have been the flashes of light witnessed by crewmen aboard the Thompson Lykes? In addition, the position of the collision is approximately where one might have expected Surcouf to be.

If the unknown vessel was indeed Surcouf, then it may be that she sank quickly with most of the hull intact and with virtually all contents of that hull trapped inside. The fact that no plates were ripped or torn from the Thompson Lykes suggests that the hull may have remained intact but, with the gun turret and other vital areas flooded, she could have sunk in this state. Such a view is speculation but would explain why no wreckage or survivors were ever found.

(Marine nationale, Ministère de la Défense Photo)

The loss resulted in 130 deaths (including 4 Royal Navy personnel), under the command of Frigate Captain Georges Louis Nicolas Blaison. The loss of Surcouf was announced by the Free French Headquarters in London on 18 April 1942 and was reported in The New York Times the next day. It was not reported Surcouf was sunk as the result of a collision with the Thompson Lykes until January 1945.

There are significant discrepancies in the story of the Surcouf’s sinking. The witness testimonies of cargo ship SS Thomson Lykes, which accidentally collided with a submarine, described a submarine smaller than Surcouf. The damage to the Thomson Lykes was too light for a collision with Surcouf. The position of Surcouf did not correspond to any position of German submarines at that moment. The Germans did not register any submarine loss in that sector during the war. Inquiries into the incident were haphazard and late. A later French inquiry supported the idea that the sinking had been due to “friendly fire”. There is no conclusive confirmation that Thompson Lykes collided with Surcouf, and her wreck has yet to be discovered.

The rumour mill was rampant after the loss of the Surcouf, with one report suggesting that she was caught in Long Island Sound refuelling a German U-boat, and both submarines were sunk, either by the American submarines USS Mackerel and USS Marlin, or by a United States Coast Guard blimp. Another unlikely story suggests that much of the gold from the French Treasury was in Surcouf’s large cargo compartment.

The disappearance of Surcouf also gave rise to a number of rumours which claimed that the accident with the Thompson Lykes was a cover story used to conceal the fact that the submarine had been deliberately destroyed by the allies. One story claimed that Royal Naval Marine divers placed mines on the hull of Surcouf while she was in harbor in Bermuda in early February, and that these were timed to detonate after she had sailed.

(Marine nationale, Ministère de la Défense Photo)

Another story claimed that Surcouf was attacked and sunk by the American submarines USS Marlin and USS Mackerel in Long Island Sound. There is a theory that the ramming by the Thompson Lykes was deliberate, with the possibility that the Thompson Lykes received a coded message instructing it to change course around 1½ hours before the collision. This would make it appear as evidence that the Thompson Lykes was deliberately routed towards the Surcouf. Another story claims that Surcouf was caught re-supplying a U-Boat somewhere south of Cape Cod and she was then attacked and destroyed by a US Navy blimp.

Another theory is that Surcouf survived the collision with the Thompson Lykes and continued to head for Panama where it was attacked and destroyed by US aircraft which mistook it for a U-Boat.

The activity of a U-Boat group in the area meant that there were certainly large numbers of anti-submarine patrols at the time. A USAAF Consolidated PBY Catalina, patrolling the same waters on the night of 18/19 February, may have attacked Surcouf believing her to be German or Japanese. The records of the USAAF 6th Heavy Bomber Group operating out of Rio Hato, Panama show them sinking a large submarine northeast of Columbus on the morning of 19 February 1942. Two Northrop A-17 Nomad and Douglas B-18 Bolo aircraft dropped eight bombs on the submarine. Since no German U-boats were lost in the area on that date, it could have been Surcouf . No other submarines were known to be in the area. It is possible that this was Surcouf and that it was accidentally sunk by US aircraft looking for U-Boats and unaware that it was in the area. It is possible the collision had damaged Surcouf ‘s radio and the stricken boat limped towards Panama hoping for the best. It is likely this information that led the French Commission which investigated the incident, to conclude that the Surcouf ’s disappearance was the consequence of misunderstanding.

(The story of her being destroyed by US Navy aircraft after the collision seems the most credible in this author’s opinion).

(Marine nationale, Ministère de la Défense Photo)

There is another theory is that Surcouf was not involved in a collision with the Thompson Lykes at all and was instead sunk by a U-Boat. The U-502 under the command of Kapitan Jurgen von Rosenstiel reported sinking seven ships in February 1942 in the Caribbean. Only six of the ships reported sunk by U-502 have been positively accounted for. On the night of 14 February, Von Rosenstiel reported an attack on a “2,400 ton tanker” in Square EC9436 (southwest of the island of Aruba and north of the Peninsula de Paraguana, Venezuela). Von Rosenstiel claimed that he watched his target burst into flames and sink rapidly after the attack but this ship has never been identified. All other reports of sinkings by U-502 are accurate and can be equated with allied losses, but not this one. It is possible that, in the darkness, Von Rosenstiel misidentified Surcouf as a tanker and attacked and sank her.

There is, in fact, a memo from FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover to the chief of U.S. Naval Intelligence dated 12 March 1942 stating that a “highly confidential source” had informed him that Surcouf had been sunk near St. Pierre. Although he doesn’t specify, it is likely that he is referring to St. Pierre in Martinique. The British Naval Liaison Officer (BNLO) had already reported some crew members discussing the possibility of taking her to Vichy French Martinique in order to defect. Unverified speculation suggests that Hoover’s source may have been Sir William Stephenson the Canadian head of British counter-intelligence in North America and the subject of the book “A Man Called Intrepid“.

During the war, Hoover wanted the FBI to be more involved in intelligence and counter-intelligence operations. Under Roosevelt several intelligence units came into being, such as the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), in addition to the existing military and naval intelligence operations. Hoover was concerned that these new units might erode the power and influence of the FBI and tried to persuade Roosevelt (unsuccessfully) that there was no need for these new and competing organizations. Because of this, Hoover was generally very careful during the early war period to ensure that any intelligence he passed on came from reliable sources. This points to a senior advisor in the intelligence field, which would suggest someone of Stephenson’s stature provided the information.

Note: The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was formed as an agency of the Joint Chiefs of Staff to coordinate espionage activities behind enemy lines for all branches of the US Armed Forces. Other OSS functions included the use of propaganda, subversion, and post-war planning. The US Army and US Navy had separate code-breaking departments: Signal Intelligence Service and OP-20-G. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) was responsible for domestic security and anti-espionage operations. President Franklin D. Roosevelt was concerned about American intelligence deficiencies. On the suggestion of William Stephenson, the senior British intelligence officer in the western hemisphere, Roosevelt requested that William J. Donovan draft a plan for an intelligence service based on the British Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) and Special Operations Executive (SOE). After submitting his work, “Memorandum of Establishment of Service of Strategic Information”, Colonel Donovan was appointed “coordinator of information” on 11 July 1941, heading the new organization known as the office of the Coordinator of Information (COI).

Thereafter the organization was developed with British assistance; Donovan had responsibilities but no actual powers and the existing US agencies were skeptical if not hostile. Until some months after Pearl Harbor, the bulk of OSS intelligence came from the UK. British Security Co-ordination (BSC) trained the first OSS agents in Canada, until training stations were set up in the US with guidance from BSC instructors, who also provided information on how the SOE was arranged and managed. The British immediately made available their short-wave broadcasting capabilities to Europe, Africa, and the Far East and provided equipment for agents until American production was established.

The Office of Strategic Services was established by a Presidential military order issued by President Roosevelt on 13 June 1942, to collect and analyze strategic information required by the Joint Chiefs of Staff and to conduct special operations not assigned to other agencies. During the war, the OSS supplied policymakers with facts and estimates, but the OSS never had jurisdiction over all foreign intelligence activities. The FBI was left responsible for intelligence work in Latin America, and the Army and Navy continued to develop and rely on their own sources of intelligence.

One extreme theory is that Surcouf managed to successfully defect to Martinique and was subsequently attacked and sunk by US aircraft operating from St. Lucia as she tried to make a run for France while being escorted by U-69 and carrying some of the bullion reserves from Fort Desaix. In this version, Surcouf is sunk sometime in May 1942. Given the Surcouf’s damaged condition, this seems most unlikely.

No one has officially dived or verified the wreck of Surcouf, therefore its precise location remains unknown. If she sank following the collision with the Thompson Lykes, then the wreck would lie 3,000 m (9,800 ft) deep at coordinates 10°40’N 79°32’W.

A monument commemorates the loss in the port of Cherbourg in Normandy, France, and the loss is also commemorated by the Free French Memorial on Lyle Hill in Greenock, Scotland. Surcouf’s honours in France include the Médaille de la Résistance avec Rosette (Resistance Medal with rosette), 29 Nov 1946. She is cited in Orders of Corps of the Army – 4 Aug 1945 and cited in Orders of the Navy – 8 Jan 1947.

Huan, Claude (1996). Le croiseur sous-marin Surcouf. Bourg en Bresse: Marines editions.

Rusbridger, James. Who Sank the “Surcouf”?: The Truth About the Disappearance of the Pride of the French Navy. Ebury Press.

(Marine nationale, Ministère de la Défense Photo)

Surcouf.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 4950919)

Royal Navy Depot Ship HMS Forth with the Free French submarine Surcouf and other Allied submarines, 1941.