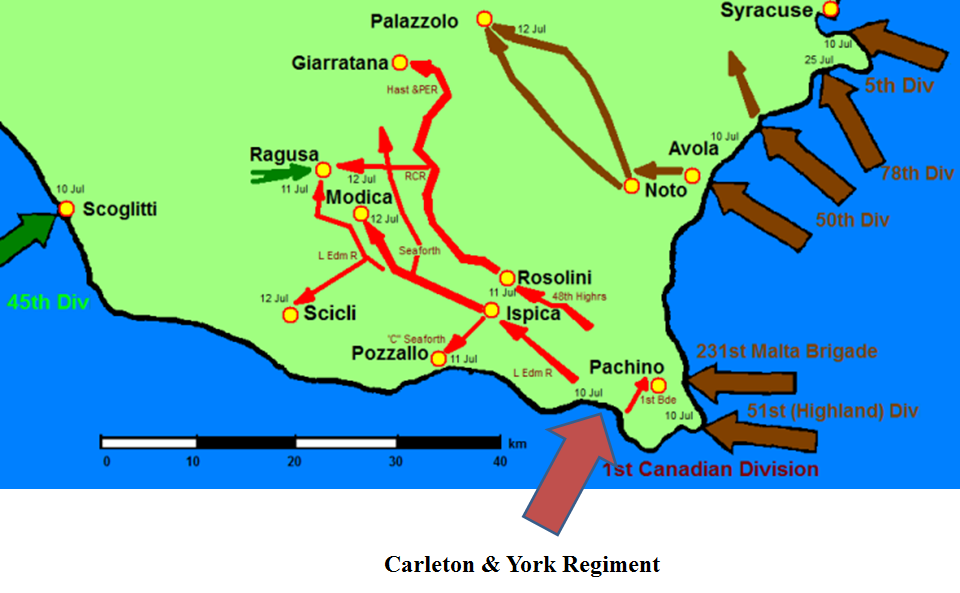

The Carleton and York Regiment, Operation Husky: Invasion of Sicily, 10 July 1943

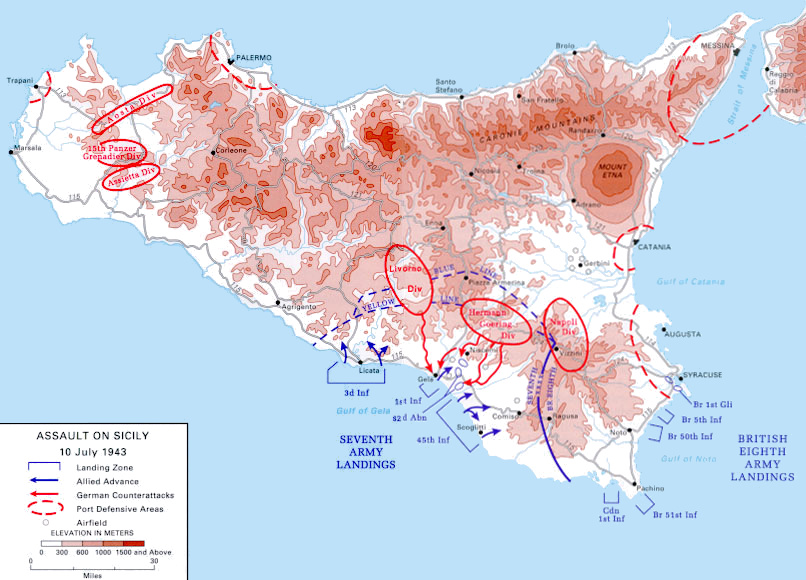

Map, Operation Husky, invasion of Sicily, 10 July 1943.

US Liberty ship Robert Rowan explodes after being hit by a German bomber off Gela on 11 July 1943.

On the night of 9-10 July 1943, an Allied armada of 2,590 vessels launched one of the largest combined operations of the Second World War, the invasion of Sicily. Over the next thirty-eight days, half a million Allied soldiers, sailors, and airmen grappled with their German and Italian counterparts for control of this rocky outwork of Hitler’s “Fortress Europe.” When the struggle was over, Sicily became the first piece of the Axis homeland to fall to Allied forces during the Second World War. More importantly, it served as both a base for the invasion of Italy and as a training ground for many of the officers and enlisted men who eleven months later landed on the beaches of Normandy.

(IWM Photo, A 17916)

Just after dawn, men of the Highland Division up to their waists in water unloading stores on a landing beach on the opening day of the invasion of Sicily. Meanwhile beach roads are being prepared for heavy and light traffic. Several landing craft tank can be seen just of the beach (including LCT 622).

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3200692)

Into battle – Carleton and York Regiment, Campochino, Italy, 23 Oct 1943.

(Author Photo)

(New Brunswick Military History Museum Collection)

The Carleton and York Regiment badge.

(Author Photo)

The Carleton York Regiment Memorial in Fredericton. 349 KIA: 28 officers and 321 other ranks severing with The Carleton York Regiment gave their lives in the service of their country while serving in the United Kingdom, Central Mediterranean Theatre and Northwest Europe in the Second World War.

(Ron Hawkins family Photo)

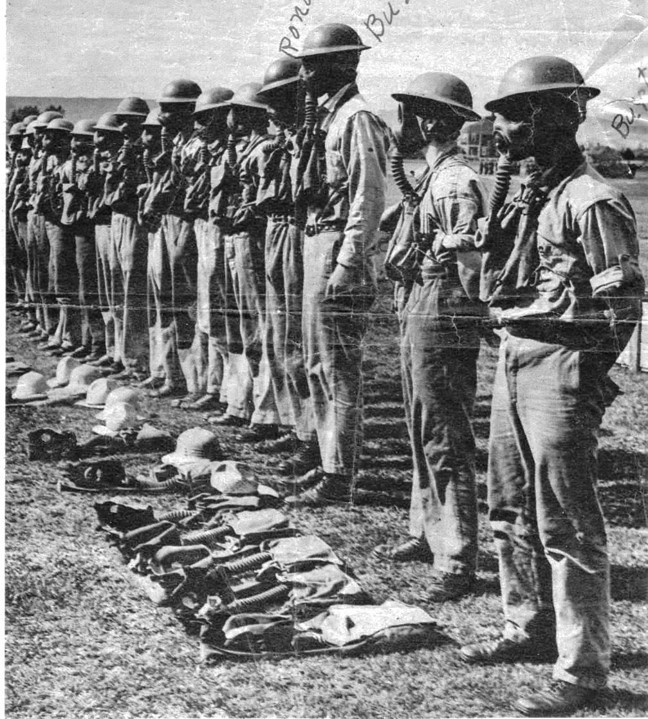

Carleton & York Regiment, gas mask drill, Island Park, Woodstock, NB, ca 1939.

When the Second World War began the Carleton York was mobilized in Woodstock, NB, on 1 Sep 1939 as a unit of the Third Brigade, First Canadian Division.

This consisted of:

“A” Company from Fredericton, men drawn from York and Sunbury Counties;

“B” Company from Woodstock, men drawn from Carleton and Victoria Counties;

“C” Company from St. Stephen and Milltown, in Charlotte County;

“D” Company from Edmundston, men drawn from Madawaska County; plus an HQ. Company.

They all moved into an established camp on Island Park, Woodstock, to begin training.

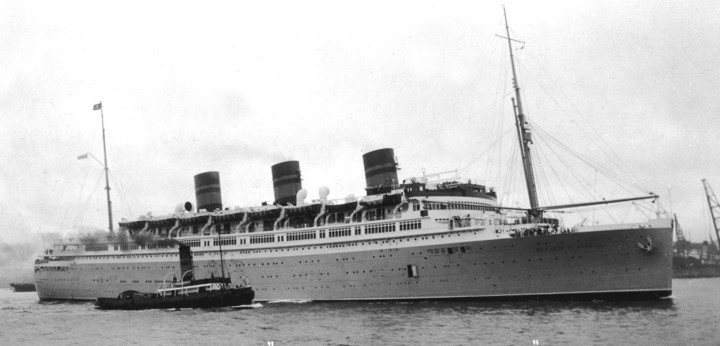

In Dec 1939, the Carleton & York Regiment sailed to England on the Monarch of Bermuda,

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3232603)

Private W.H. Morris of The Carleton and York Regiment, who holds a field wireless set, taking part in a training exercise prior to the invasion of Sicily. England, 26 May 1943.

The assault on Sicily was to be the prelude to the invasion of mainland Europe. The invasion was assigned to the Seventh U.S. Army under Lieutenant General George S. Patton, and the Eighth British Army under General Sir Bernard L. Montgomery. The Canadians were to be part of the British Army.

The 1st Canadian Infantry Division and the 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade, under the command of Major-General G.G. Simonds, sailed to Sicily from Great Britain in late June 1943.

Canadian troops en route to Sicily.

En route, 58 Canadians were drowned when enemy submarines sank three ships of the assault convoy, and 500 vehicles and a number of guns were lost. Nevertheless, the Canadians arrived late in the night of July 9 to join the invasion armada of nearly 3,000 Allied ships and landing craft.

U-boat.

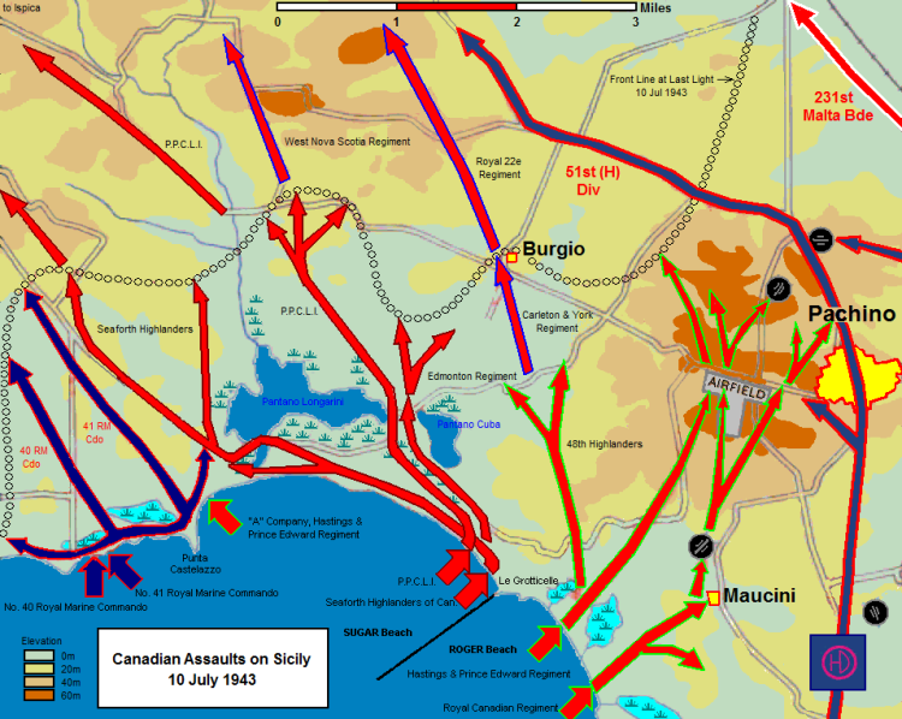

Map. On 10 July 1943, the Carleton & York Regiment landed at Pachino in the opening waves of the Allied Invasion of Sicily. Operation Husky, began with a large amphibious and airborne operation, followed by a six-week land campaign.

(German Army Photo)

At the time of the invasion in July 1943, there were 70,000 German troops in Sicily, Panzer Division Herman Göring, 15th Panzergrenadier Division, 1st Parachute Division, 29th Panzergrenadier Division, and the XIV Panzer Corps headquarters (General der Panzertruppe Hans-Valentin Hube), plus 200,000 Italian troops.

(German Army Photo)

Benito Mussolini inspecting German troops, Sicily, Italy, 25 Jun 1942.

(German Army Photo)

15th Panzer Division.

(Italian Army Photo)

The Italian units in Sicily made up the Sixth Army commanded by General Alfredo Guzzoni. It was divided into two Corps; the XII and XVI, and comprised five coastal

divisions, two coastal brigades and a coastal regiment all arranged in static formations around to the coast, all of low morale and zero combat experience. The Army also had four field divisions: 4ª (Livorno), 26ª (Assieta), 28ª (Aosta) and 54ª (Napoli), as well as five ports and naval bases, and several airfields with their own defensive units.

Troops preparing to board Waco gliders. Airborne landings went in just before dawn on 10 July 1943, followed by the assault on the beaches. The first landings were made by the British, using more than 130 gliders of the 1st Airlanding Brigade. Their task was to take control of a bridge, the Ponte Grande, some distance to the south of Syracuse. However, the landings were fraught with problems: 200 men were drowned when their gliders crashed into the sea, many more landed in areas away from their target, and only 12 landed in the right place. Even so, the British were successful in taking and holding the bridge.

(Paolo Marzioli Photo)

US Paratroopers, Sicily, 1943.

Meanwhile, American paratroopers were attempting a landing in another part of Sicily, but this operation, too, went far from smoothly. Many of the pilots used had little experience of combat and a combination of this inexperience, dust being thrown up from the dry ground, and fire from anti-aircraft guns meant that the U.S. paratroopers, more than 2,700, ended up quite widely spread, some landing as much as 50 miles away from their targets.

(IWM Photo, NA 4275)

Canadian troops went ashore near Pachino close to the southern tip of Sicily, 10 July 1943.

(DND Map)

Map. The Canadians formed the left flank of the five British landings that spread along more than 60 kilometres of shoreline.

(DND Map)

Map. Three more beachheads were established by the Americans over another 60 kilometres of the Sicilian coast. In taking Sicily, the Allies aimed, as well, to trap the German and Italian armies and prevent their retreat across the Strait of Messina into Italy.

(DND Photo)

From the Pachino beaches, where resistance from Italian coastal troops was light, the Canadians pushed forward through choking dust, over tortuous mine-filled roads.

The main assault on the Sicilian coast had been a joint effort between British and U.S. forces, with American divisions attacking the western coasts and the British the east. Warships were based off the coasts in order to provide covering fire. The British forces had the easier time of the two groups, with relatively little fight being put up by the Italian defenders. This allowed the Allied guns and tanks to be landed quickly, and Pacino was in British hands by nightfall.

Meanwhile, the U.S. divisions on the other coast of the island had a much harder time of things, with both Italian and German airplanes offering strong resistance to the invasion. Later in the afternoon, a Panzer division of heavy Tiger tanks joined the defence, but the Americans managed to land 18 Regimental Combat Team and the 2nd Armored Division by evening. The U.S. forces succeeded in holding their ground until covering fire from the Navy drove off the tanks.

(DND Map)

Map. Route Canadians followed in Operation Husky.

Tiger tank. Resistance stiffened as the Canadians were engaged increasingly by determined German troops who fought tough delaying actions from the vantage points of towering villages and almost impregnable hill positions. On July 15, just outside the village of Grammichele, Canadian troops came under fire from Germans of the Hermann Goering Division. The village was taken by the men and tanks of the 1st Infantry Brigade and Three Rivers Regiment.

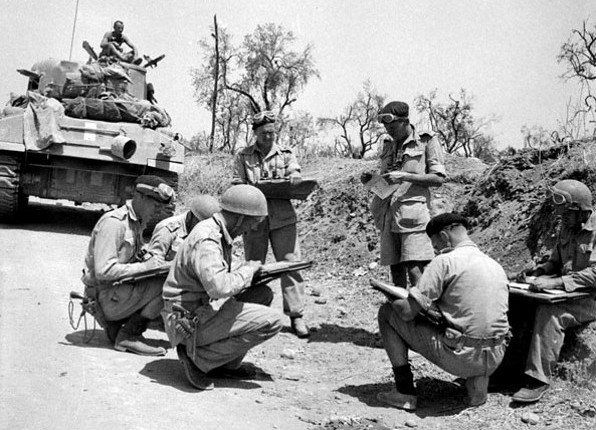

O Group. Piazza Armerina and Valguarnera fell on successive days, after which the Canadians were directed against the hill towns of Leonforte and Assoro. Despite the defensive advantages which mountainous terrain gave to the Germans, after bitter fighting both places fell to the Canadian assault.

(German Army Photo)

Even stiffer fighting was required as the Germans made a determined stand on the route to Agira. German Sd.Kfz 138/1 Grille Mobile Howitzer/SPA with a 4-man crew, and an Sd.Kfz. 251 parked in front of an Electricity store. M4A2 Sherman disabled in the background.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 4997400)

Supermarine Spitfire Mk. V, No. 417 Sqn, RCAF, Sicily, 26 Aug 1943.

Three successive attacks were beaten back before a fresh brigade, with overwhelming artillery and air support, succeeded in dislodging the enemy. On 28 July, after five days of hard fighting at heavy cost, Agira was taken.

Americans were clearing the western part of the island while the British were pressing up the east coast toward Catania. These operations pushed the Germans into a small area around the base of Mount Etna where Catenanuova and Regalbuto were captured by the Canadians.

The Axis were misled by the widely scattered Allied paratroopers into thinking that the invasion was on a massive scale and requested reinforcements. However, these did not make a difference to the eventual outcome. On July 12, Augusta had come under British control, and General Bernard Montgomery ordered his men to mount an attack on Messina to the north. Lt. General George S. Patton, who commanded the American 7th Army, did not agree with this change in emphasis and told his troops to head west instead.

The U.S. soldiers advanced steadily toward Palermo, a strategically important seaport. They met relatively little serious resistance and, by the time they had occupied the port on July 22, more than 50,000 prisoners had been taken. Control of Palermo allowed the 9th Division of the U.S. Army to make a landing there, rather than having to repeat a riskier southern assault; it also opened up a useful supply line for the Allies. Once this had been achieved, Patton was ordered by Alexander to go forward to Messina.

(IWM Photo)

The British 8th Army had things rather less its own way, with both stiff resistance from German paratroopers and the craggy Sicilian interior making progress difficult. The Germans were also aided by their 8.8-cm anti-tank guns, but eventually the towns of Biancavilla, Catania, and Paterno were captured for the Allies.

(Author Photo)

German 8.8-cm Pak 43 AT Gun preserved at the Royal Military College in Kingston, Ontario.

Meanwhile, Canadian forces under Lord Tweedsmuir’s command mounted a successful surprise assault on Assoro and Leonforte by climbing a cliff which seemed inaccessible and so had been left undefended.

(IWM Photo)

British troops scramble over rubble in a devastated street in Catania, Sicily, 5 August 1943.

(DND Photo)

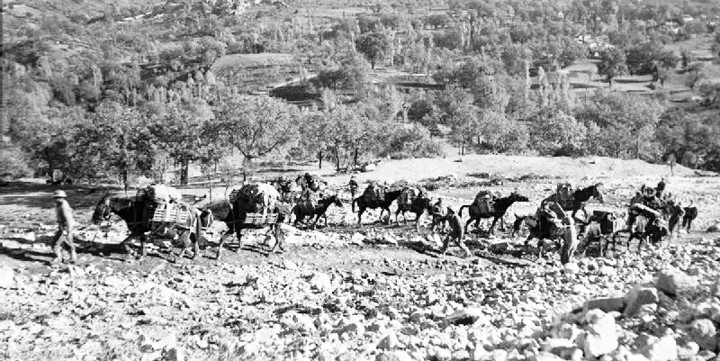

The final Canadian task was to break through the main enemy position and capture Adrano. Here, they continued to face not only enemy troops, but also the physical barriers of a rugged, almost trackless country. Mortars, guns, ammunition, and other supplies had to be transported by mule trains. Undaunted, the Canadians advanced steadily against the enemy positions, fighting literally from mountain rock to mountain rock.

(RAF Photo)

Operation Husky/Invasion of Sicily. A Martin Baltimore flies over its target, retreating German forces heading for Messina, July 1943.

(IWM Photo)

With the approaches to Adrano cleared, the way was prepared for the closing of the Sicilian campaign. The Canadians did not take part in this final phase, however, as they were withdrawn into reserve on 7 Aug. Eleven days later, British and American troops entered Messina. Sicily had been conquered in 38 days.

By early August, Sicily was largely under the control of the Allies. American and British armies hurried to reach Messina first, with the Axis prevented from blowing up bridges by advanced airborne forces. The U.S. forces won the race to Messina by less than one hour, reaching it on the morning of August 17. They found that the German defenders had already been evacuated, but in such a rush that enormous caches of valuable fuel, guns, and ammunition were still present.

Messina itself had been largely ruined by Allied bombs and Italian defensive shells, but Operation Husky as a whole was a total success for the Allies. The goal of exposing what was known as Europe’s “soft underbelly” had been achieved, and the Mediterranean made secure for Allied shipping. Nevertheless, it was one of the bloodier contests of World War 2: casualties on the Allied side numbered about 25,000, while as many as 160,000 German and Italian soldiers were killed, wounded or captured.

(German Army Photo)

German evacuation of Sicily. 11 -17 August 1943. While the invasions of Sicily and Italy are quite well known, the importance of the Axis evacuation of Sicily has been terribly overlooked. During this week, the Axis Powers were able to evacuate 50,000 German and 75,000 Italian troops across the Straight of Messina to mainland Italy. The Allies were unable to prevent this because the invasion plan didn’t account for troop exhaustion, and lack of reserves. The Germans also conducted an expert rearguard action to slow down the Allied progress.

(DND Photo)

Canadian Cemetery Memorial, Agira, Sicily. Canadian casualties throughout the fighting totalled 562 killed, 1,664 wounded and 84 prisoners of war.

…and the fighting continued in Italy.

(C&Y Photo Archive)

Carleton and York Regiment with M10 TD.

The Carleton and York Regiment moved to France during Operation Goldflake in March 1945.

(NBMHM Photo)

Carleton & York Regiment soldiers fighting in the Netherlands, 1945.

(NBMHM Photo)

Carleton & York Regiment soldier in a jeep is crowded by newly liberated Dutch civilians, Leidschendam, Netherlands, 7 May 1945.

The Carleton and York Regiment is perpetuated in the Royal New Brunswick Regiment.