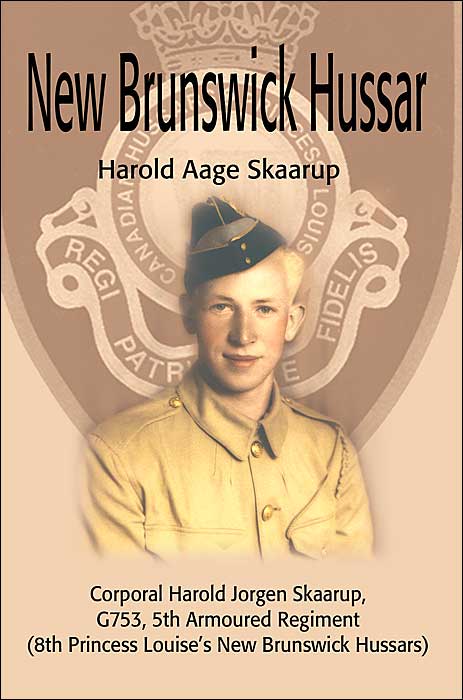

New Brunswick Hussar, Corporal Harold Jorgen Skaarup

In April 1941, my uncle Harold Jorgen Skaarup, raised in the Danish community of New Denmark, New Brunswick, came down to the City of Fredericton and joined the Canadian Army. His parents Anne and Frederick were well aware of the potential horror of war that Harold would face. Fred had been wounded many times in the First World War and Anne had received letters that Fred had been reported killed in action on three separate occasions. One can well imagine the heaviness in their hearts as their son became a soldier – and the worry of what could happen to him. Their fears were well-founded.

Harold served with the 8thCanadian Hussars until he was wounded when his tank was hit by a Germananti-tank gun near Monteccio in Italy in August 1944. He died from his wounds a few days later. I can imagine how hard it must have been when an Anglican minister from Centreville came into the driveway of their farm and delivered the telegram to my grandmother Anne. “It was with deep regret that I learned of the death of your son, G753 Lance Corporal Harold Jorgen Skaarup, who gave his life in the service of his Country in the Mediterranean Theatre of War, on the 6th day of September 1944.” The horror of war had come home to her again.

My uncle Frederick Estabrooks served with the Canadian Provost Corps and was in the European theatre when he was injured by an artilleryshell and put in the hospital for several months. For both families, the end of the war could not come soon enough. More than 45,000 Canadian servicemembers did not survive the war. When asked what I think of the 80thanniversary of VE day, it is of the families who were fortunate enough to have had their loved ones survive to come home. Harder, is thinking about what the war did to the families that did not have one of theirs return.

We had fatalities inthe Canadian Forces while I served at home and overseas during the Cold War. Every single one of them was hard on those of us who knew and served with them. We were glad tocome home mostly intact. Some did not and find it hard to cope. For those who made it back after VE day, many of them must have found it just as hard. They must not be forgotten. As you have often heard on Remembrance Day, there is a line from Laurence Binyon’s poem “For the Fallen”, “At the going down of the sun, and in themorning, we will remember them.”

Major (Retired) Harold Aage Skaarup

Corporal Harold Jorgen Skaarup, G753, from New Denmark and Carleton County, New Brunswick was a Sherman tank commander in “A” Squadron of the 5th Armoured Regiment, 8th Princess Louise’s New Brunswick Hussars during the Second World War.

On the morning of the 31 August 1944, Harold and his tank crew were fighting the Germans in Italy near a hill known as Point 136. His squadron had already lost 12 of 19 tanks, ten to German 88-mm anti-tank shells and two to breakdowns. That morning, Harold’s tank was hit by another 88-mm shell and Harold was badly injured. Although he and his tank crew bailed out of the burning Sherman, mortar rounds began to land on them. Harold was hit again, this time taking shell fragments in his chest. He was evacuated to a field hospital in the rear area, but died of his wounds (DoW) on 6 September 1944. He was 24 years old. Today he lies buried in a Commonwealth War Grave in Montecchio, Italy. He never got home to tell his story. New Brunswick Hussar is a partial chronicle of his service, by his nephew. We never met, but I do carry his name.

Harold Aage Skaarup, Former Honorary Lieutenant-Colonel for 3 Intelligence Company.

You can order this book on line here:

https://www.chapters.indigo.ca/en-ca/books/new-brunswick-hussar-corporal-harold/9780595747689-item.html?ikwid=New+Brunswick+Hussar&ikwsec=Home&ikwidx=1#algoliaQueryId=8704b47489e2a56f0f5e25a3df181baa

https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/new-brunswick-hussar-harold-a-skaarup/1120547871?ean=9780595747689

https://www.iuniverse.com/BookStore/BookDetails/116977-New-Brunswick-Hussar

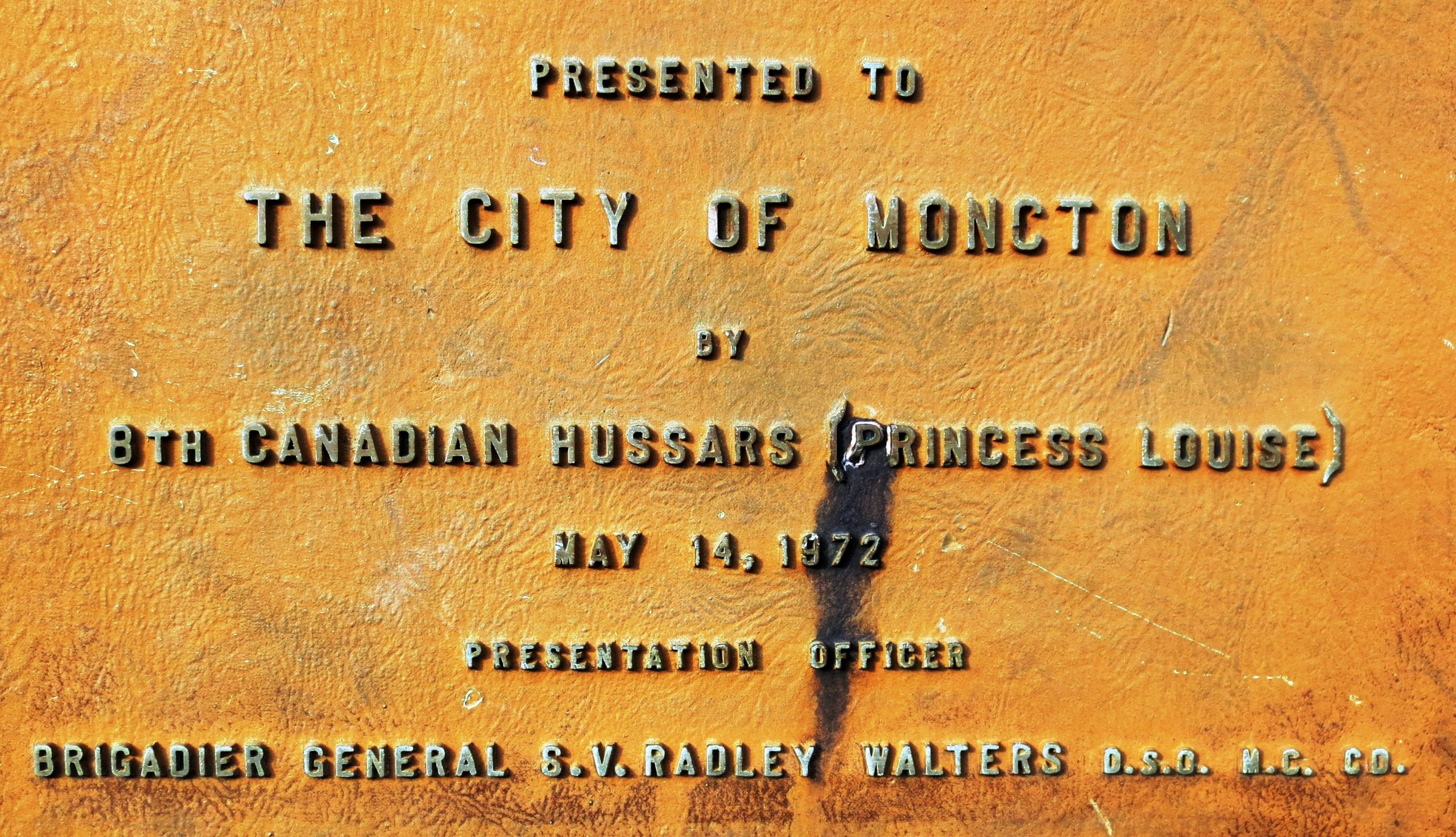

8th Princess Louise’s New Brunswick Hussars

Foreword

This story is about Cpl Skaarup who was but one of a number of 8th Hussars to lose his life in the service of his country. He, like most of his brothers in arms, was an average man who answered the call to arms for many and varied reasons, but above all he was a good Canadian. Unfortunately, he never came back to tell his story, so we must rely on the official records and the reports of the survivors he served with to understand what really happened to him during that period of the war in Italy. These days, few of the original Hussars are left alive. As time marches on, the living history of the regiment dims with the passing of each veteran. For those who have never served in the armed forces, “New Brunswick Hussar” outlines the story of one Hussar from a family and historical point of view. For those who are in the military, the story is an all too familiar one – a Canadian soldier serves overseas, trains hard under difficult conditions, is deployed to the front, and is killed in the service of his country. This book serves as a remembrance of Cpl Skaarup and for those 8th NB Hussars who served with him. You should find it an interesting and informative read.

Lieutenant-Colonel Larry J. Zaporzan, Commanding Officer, 8th Canadian Hussar, Moncton, New Brunswick, 2001.

Major (Retired) Harold Aage Skaarup at the Woodstock cenotaph, 11 Nov 2023. Cpl Harold Jorgen Skaarup’s name is on the cenotaph behind him.

Youtube video honouring Harold:

The Lest We Forget videos were created by students from Stephen Wilson’s Grade 12 Canadian History classes at Belleisle Regional High School from 2008 to 2016. Belleisle Regional High is located in Springfield, NB, Canada. They pay homage to Canadian soldiers who paid the ultimate sacrifice in service to their country. Another group of videos are on a sister Youtube channel site: wilsostj. The work of Belleisle students has been continued by summer employees of the 8th Hussars Museum located in Sussex, NB since 2017. Written biographies for each soldier video can be found by searching the soldier on The Canadian Virtual War Memorial web site. These biographies were written by the same students who created the videos.

The Centreville cenotaph has 12 of 14 family names on this memorial! Grandfathers Fred Skaarup and Walter Estabrooks, both gunners, fought in the First World War, uncles Harold Jorgen Skaarup, 8th Hussars, died of wounds in Italy, Sep 1944, and Fred Estabrooks, C Pro C, Second World War. For the Cold War era, my father WO Aage C. Skaarup, RCAF, uncle WO Carl Skaarup, RCEME, uncle Bernard Estabrooks, C Pro C, aunt Wilhelmine Estabrooks, CWAC (did not want her name on the stone), cousin Fred Skaarup, RCA, brother Lt (Navy) Dale Ray Skaarup, RCN, brother Christopher Loren Skaarup, RCA, Former HLCol Harold Aage Skaarup, C Int C. sister-in-law Lt (Navy) Heather Skaarup, (not on the stone), and my son 2Lt Sean Jordan Skaarup, RCA. My mother Beatrice Lea Skaarup (nee Estabrooks), my wife Faye Alma Jenkins and son Jonathan Mark Skaarup have been tremendous support throughout our numerous deployments.

Corporal Harold Jorgen Skaarup

Corporal Harold Jorgen Skaarup, G753, from New Denmark and Carleton County, New Brunswick was a Sherman tank commander in “A” Squadron of the 5th Armoured Regiment, 8th Princess Louise’s New Brunswick Hussars during the Second World War.

On the morning of the 31 August 1944, Harold and his tank crew were fighting the Germans in Italy near a hill known as Point 136. His squadron had already lost 12 of 19 tanks, ten to German 88-mm anti-tank shells and two to breakdowns. That morning, Harold’s tank was hit by another 88-mm shell and Harold was badly injured. Although he and his tank crew bailed out of the burning Sherman, mortar rounds began to land on them. Harold was hit again, this time taking shell fragments in his chest. He was evacuated to a field hospital in the rear area, but died of his wounds (DoW) on 6 September 1944. He was 24 years old. Today he lies buried in a Commonwealth War Grave in Montecchio, Italy. He never got home to tell his story. New Brunswick Hussar is a partial chronicle of his service, by his nephew. We never met, but I do carry his name.

Harold Aage Skaarup, Former Honorary Lieutenant-Colonel for 3 Intelligence Company.

8th Princess Louise’s New Brunswick Hussars

(York Sunbury Historical Society, Fredericton Region Museum Collection, Author Photo)

Accession No. 1997.28.10. 8th Canadian Hussars (Princess Louise’s).

Foreword

This story is about Cpl Skaarup who was but one of a number of 8th Hussars to lose his life in the service of his country. He, like most of his brothers in arms, was an average man who answered the call to arms for many and varied reasons, but above all he was a good Canadian. Unfortunately, he never came back to tell his story, so we must rely on the official records and the reports of the survivors he served with to understand what really happened to him during that period of the war in Italy. These days, few of the original Hussars are left alive. As time marches on, the living history of the regiment dims with the passing of each veteran. For those who have never served in the armed forces, “New Brunswick Hussar” outlines the story of one Hussar from a family and historical point of view. For those who are in the military, the story is an all too familiar one – a Canadian soldier serves overseas, trains hard under difficult conditions, is deployed to the front, and is killed in the service of his country. This book serves as a remembrance of Cpl Skaarup and for those 8th NB Hussars who served with him. You should find it an interesting and informative read.

Lieutenant-Colonel Larry J. Zaporzan, Commanding Officer, 8th Canadian Hussar, Moncton, New Brunswick, 2001.

(Oromocto Legion Branch 93 Collection, Author Photo)

5th Armoured Regiment (8th Princess Louise’s (New Brunswick) Hussars, CAC, CASF, Second World War cap badge.

Introduction

During the Second World War Canada fielded an army of three infantry divisions and two armoured divisions for service overseas, and raised another three divisions for home defence for a total of eight.[1] In the winter of 1941 the Canadian government decided that the 8th Princess Louise’s New Brunswick Hussars should be part of the first two armoured divisions being raised, and therefore directed that the unit be placed in a tank role.[2] In April 1941, at the age of 22, Harold Jorgen Skaarup joined the 5th Armoured Regiment of the 8th Hussars in Fredericton, New Brunswick. He participated in roughly three weeks of basic instruction at a training camp near the present day Exhibition Grounds in Fredericton along with a number of other new recruits from New Brunswick. They were then transported by train to Camp Borden, Ontario, for their initial instruction in the use of tanks and other armoured vehicles at the armoured school based there, some 80 km north of Toronto. On completion of this instruction, the tank soldiers of the 8th Hussars went to England by ship to continue their training.[3] During their tour of duty in the UK, the 8th Hussars became part of the 5th Canadian Armoured Division.[4]

730,625 Canadian men and women served in the Armed Forces of Canada during the Second World War, and of these, 24,870 soldiers were killed and 58,094 were wounded, 17,974 Airmen and 4,154 sailors lost their lives and many more were wounded.[5] Harold J. Skaarup was one of the Canadians who never came home at the end of the war. Most of those who died with him were young people. They deserve to be remembered, and this record is meant as a tribute to their sacrifice.

Canada at War

War had been building for some time in Europe when suddenly the armed forces of Germany swept into Poland on 1 September 1939. Shortly afterwards, the Russian Army joined the Germans in carving up the Polish nation, driving across the Polish frontier from the East in a surprise attack. Somewhere in the mists of diplomatic manoeuvring, the nations of Britain and France had signed agreements that bound them to defend Poland). As a result, on the 4th of September, Britain and France declared war on Germany. Although Canada had not been involved in formation of these agreements, the Canadian government assembled in an emergency session on the 7th of September 1939 to decide whether or not it would support the declarations made by England and France. The consequences of Canada’s participation in the Great War of 1914-1918 and the appalling loss of life had not been forgotten. A total of 619,636 men and women served in the Canadian Army in the First World War, and of these 59,544 gave their lives and another 172,950 were wounded.[6] Canada had signed the Peace Treaty as a nation in its own right, and therefore the deliberations to go to war again were given careful consideration. The decision was made to support the British and French on the 9th of September. On the 10th of September 1939, King George VI proclaimed the existence of a state of war between Canada and Germany.[7]

In December 1939, the 1st Division of Canadian volunteers in the “Canadian Active Service Force” (CASF) went overseas to Britain under the command of Major-General A.G.L. McNaughton. By February 1940, there were some 23,000 Canadian Forces on duty in England. Poland had surrendered on the 27th of September 1939, and it had then been partitioned by Germany and Russia. In hindsight, it is remarkable that Britain, France, and its Canadian ally did not declare war on Russia, even though they had also invaded Poland, which was supposedly the reason Britain and France had declared war on Germany. In fact, if the west had any thoughts on the subject, they were downright indignant and angry over the Russian invasion of Finland, which ended on the 12th of March 1940. As these events unfolded, families in New Brunswick were listening to regular news reports, which included such stirring events as “the Battle of the River Platte” which ended with the scuttling of the German pocket battleship Graf Spee off the shores of Montevideo, Uruguay after a running sea battle with British warships.

With the coming of spring, the “phony war” changed to a hot one. On the 9th of April 1940, the Germans invaded Denmark and Norway. Overnight, the Germans occupied and took control of Denmark, and Norway was forced to surrender by the 3rd of May. The invasion of the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg followed on the 10th of May, and this led to the resignation of Britain’s Prime Minister Chamberlain, who had failed to achieve “peace in our time” with a policy of appeasement. That same day, Winston Churchill became Great Britain’s new leader. The situation on mainland Europe steadily deteriorated as Holland capitulated on the 14th of May. By the 26th of May, the Germans had driven the allies into the sea at Dunkirk. In spite of the surrender of Belgium on the 28th of May, an historic evacuation of 340,000 Allied troops to Britain continued from the beaches of Dunkirk until the 4th of June. To complicate matters even more, the Italians declared war on Britain and France on the 10th of June, which in turn led to Canada’s declaration of war on Italy. The Germans, Italians and Japanese would eventually forge a coalition called “the Axis.”

Paris fell to the Germans on the 14th of June, and this led to the French signature on an armistice with Germany in the same railway car that the French had taken the surrender from Germany, this time on the 22nd of June 1940. A new French capital was created under Marshall Pétain, at Vichy, and the German occupied area of France became known as “Vichy France”. The Germans now stood ready to invade England under a plan called “Operation Sea Lion.” Those Canadians already deployed overseas made ready to defend England as the 7th Corps under Canada’s General McNaughton. This Corps consisted of the 1st Canadian and 1st Armoured Divisions. The Battle of Britain began in September, with the German Luftwaffe carrying out a series of massive air attacks against England. These were successfully fought off by a small number of Commonwealth aircrews, including a number of Canadians. The Germans suffered unsustainable air losses, and this brought their invasion efforts to a halt. By the 17th of September 1940, the German invasion had been postponed indefinitely.[8]

During these critical events in 1940, the 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade, the 3rd Division and the 5th Armoured Division sailed to Britain.[9] The 7th Corps was disbanded on the 25th of December 1940, but in its place the Canadian Corps was formed. Families who had been following the war news learned of the sinking of the terrible loss British battleship Hood (there were only three survivors) by the German battleship Bismark in the Atlantic on the 24th of May 1941. The Bismark was in turn caught and sunk by a combined force of British aircraft and warships on the 27th of May.

On the 22nd of June 1941 the Germans invaded Russia across a wide front from the Black Sea to the Baltic Sea in an attacked dubbed “Operation Barbarossa.’ Italy, Romania and Finland also found themselves at war with Russia. The immediate result for the defenders of Britain was that they were now given a respite from the heavy pace of German air attacks. More importantly, they were able to use this time to rebuild their depleted air. sea and ground forces, and to re-arm and train them in preparation for the return to Europe.[10]

Joining up

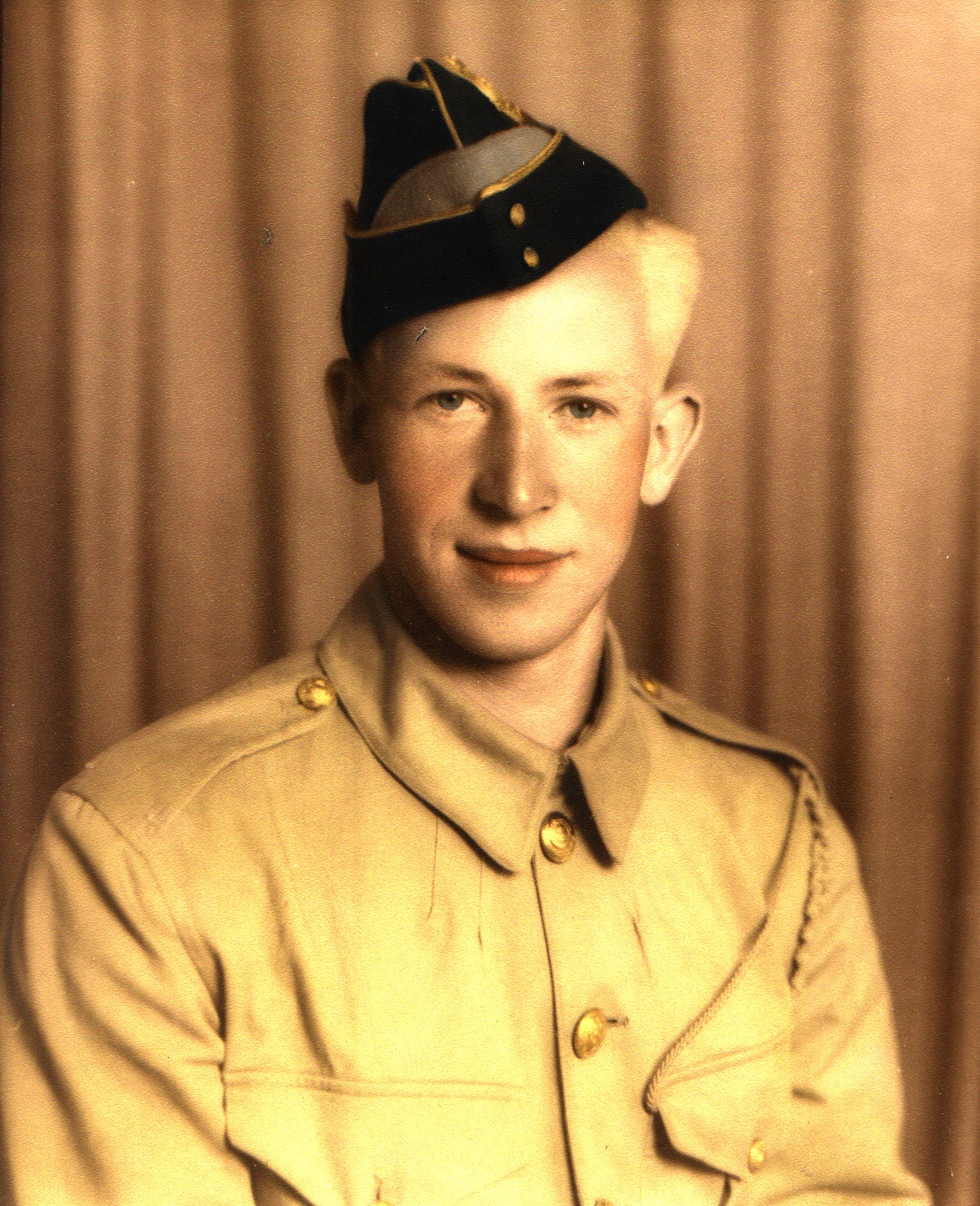

In April 1941, Harold J. Skaarup joined the army. He had been born on the 27th of September 1919 in Broager, a small town in South Jutland, Denmark. Harold was the second of four sons of Frederick and Anne Skaarup. The family had immigrated to Canada, with Frederick arriving in 1926 on the SS Montcalm, and Anne and her sons following in 1926 on the SS United States. They made their first home in the Danish community of New Denmark in the province of New Brunswick. They lived there on a farm not far from Klokkedahl Hill (named after a man who lived there, who was a clock maker), until early 1940 when they moved to Charleston, six miles south of the small village of Centreville.

Harold was a very good skier and all around good at sports. He was also an especially good softball pitcher (left handed), being the pitcher for the River de Chute team. In 1939 they took on the Centreville team and trimmed them up in style![11]

Harold’s older brother Fred lived in River de Chute, his younger brother Aage lived in Charleston and Carl, the youngest brother, lived in Kincardine, all in New Brunswick. All have passed on.

Harold enlisted in Fredericton along with many other men from New Brunswick. There were two boys from New Denmark who joined at the same time as Harold, one was Cecil Hansen and the other was Alfred Sorensen. Alfred and Harold were good friends, and Alfred stayed with the same group of Hussars right to the end. These boys were all good skiers, and Harold often got into the top four or five placings at the ski contests.

Mr. William Crain, a friend of Harold’s, recalls that five men at a time put their hands on the Bible and were sworn in. They stayed in Fredericton at an army camp that is now the site of the Fredericton Exhibition grounds, where they completed three weeks of basic training. From there the men who had joined the 8th Hussars were sent by train to Camp Borden, Ontario, for advanced training at the Armoured Corps School based there. As a side-note, Canadian Forces Base (CFB) Borden continues to be a major training base for a large number of schools within the Canadian Forces (CF). A number of historical armoured vehicles and a great deal of Armoured Corps memorabilia are available for viewing in an excellent display at the Base Borden Military Museum. Also, many of the armoured vehicles Harold would have trained on have been photographed at the Borden museum are used to illustrate sections of this book. The Armour School has been relocated for some time to the Combat Training Centre (CTC) based at CFB Gagetown, now 5 Canadian Division Support Base Gagetown, near Oromocto in New Brunswick. The author served at the CTC Tactics School and later as the G3 DCO at Base HQ.

Family photo with Harold’s mother Anne, his brother Carl, Harold in uniform, his older brother Fred Jr and his father Fred Skaarup on the family farm in Carleton County, New Brunswick. The picture was likely take in September 1941, shortly before he went overseas. His younger brother Aage may have taken the picture.

Training in Canada

M1917 tanks arrive at Camp Borden, Oct 1940. (Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3563837)

M1917 tanks arrive at Camp Borden, Oct 1940. (Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3325255)

M1917 tanks arrive at Camp Borden, Oct 1940. (DND Photo)

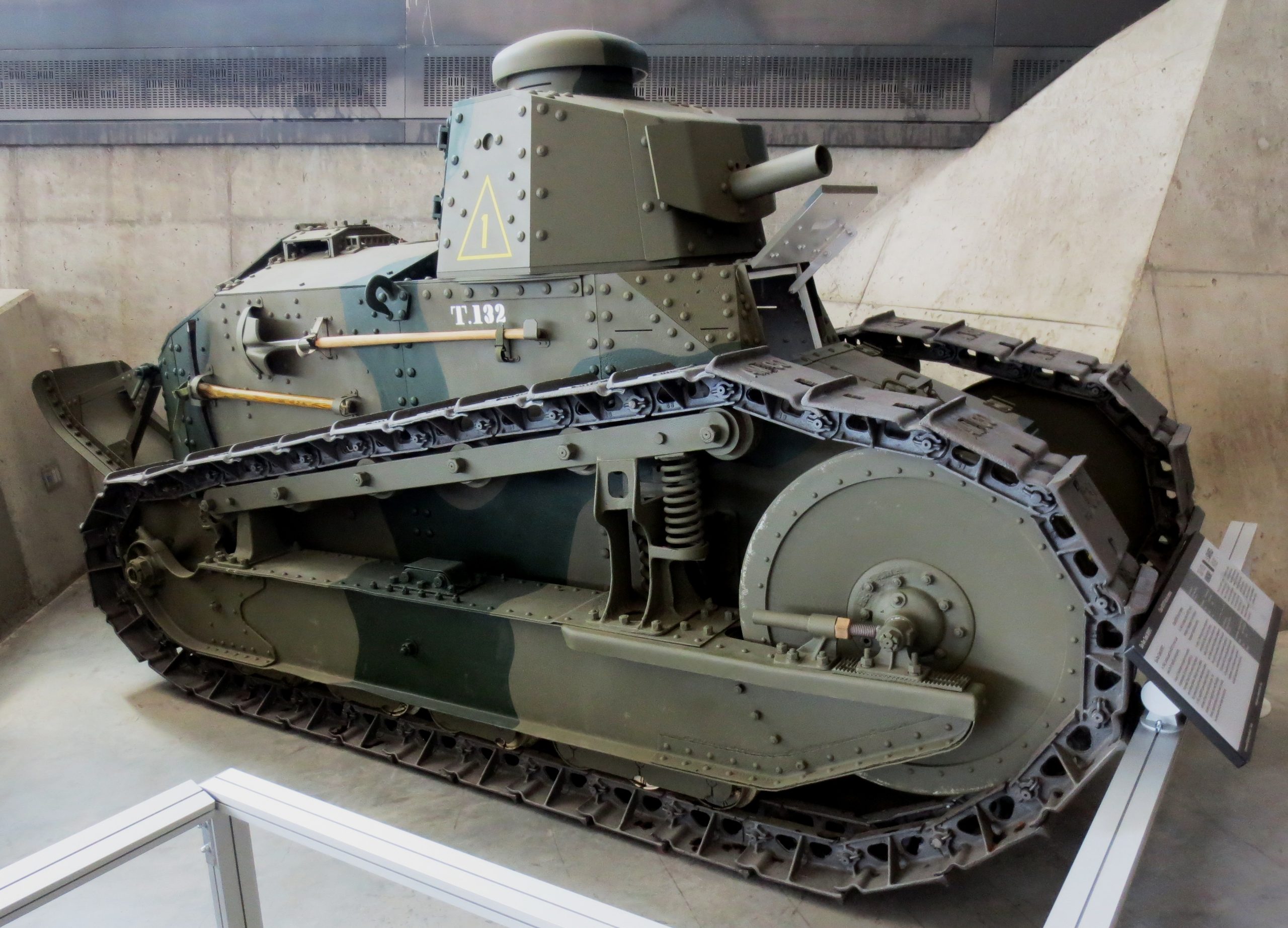

M1917 tank on display in the Canadian War Museum, Ottawa, Ontario. (Author Photo)

The first tank that Harold would have begun his training on at the Armoured Corps Training Centre at Camp Borden, was a First World War era tank that the Americans had built called the M1917 (a copy of the French Renault tank). Only a handful of the M1917 tanks were initially available, but they were used extensively to train the men as drivers and to get them used to handling a tank.

The M1917s were described by the 8th Hussar’s Regimental Sergeant Major (RSM) as “low-slung things with a sort of pillbox cab for the men.” They had no suspension tracks and consequently the men were given a pretty rough and jarring ride. There was very little room for two people inside the tank, but the second man was needed as things were “always catching fire and a bucket of water or sand had to be kept handy to put the fire out.” Although the tank could go 8-10 mph, they seldom got very far, due to mechanical breakdown.[12]

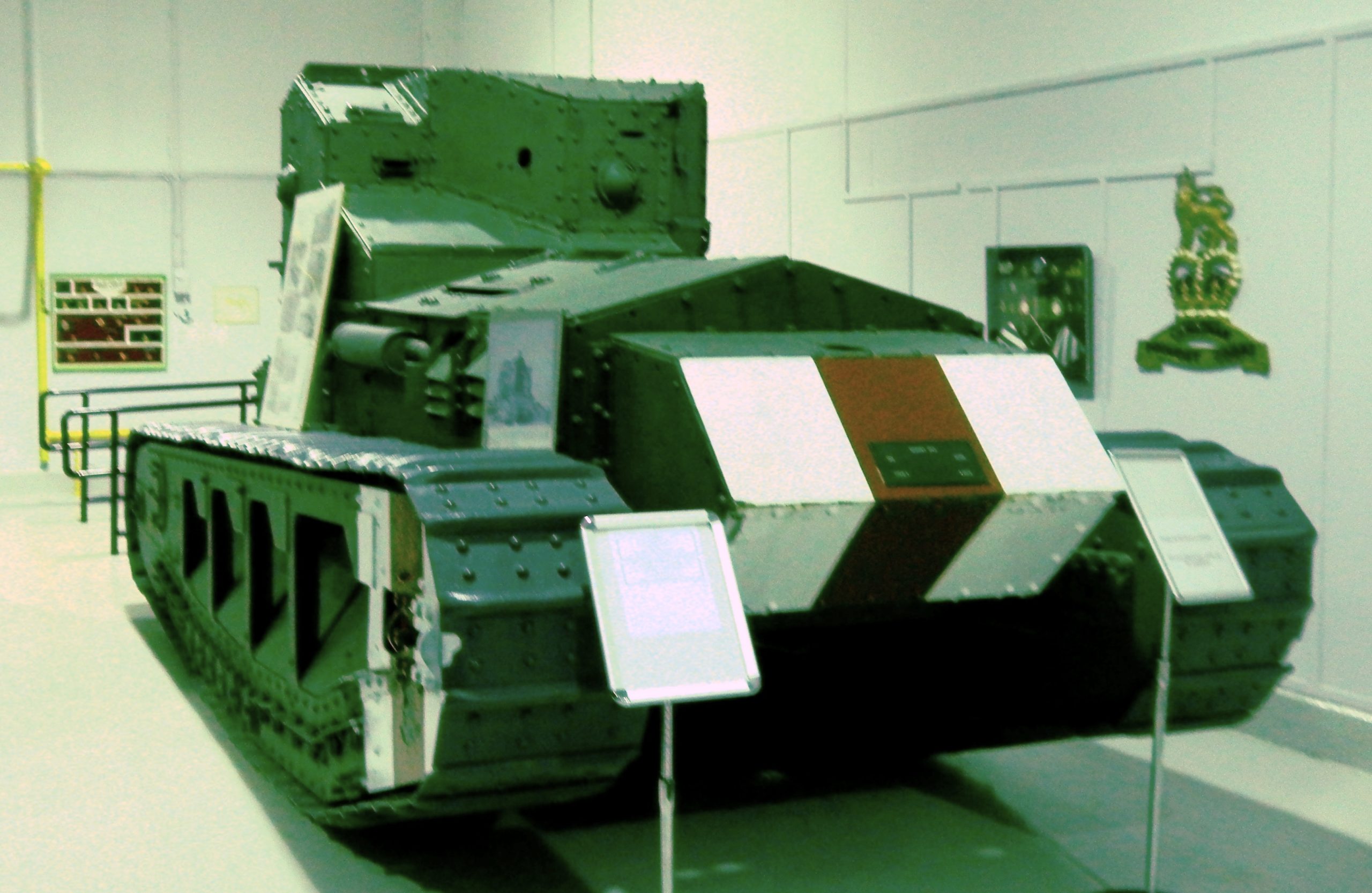

British Whippet tanks, Achiet-le-Petit, France, 22 Aug 1918. (NLNZ Phto)

Harold standing beside a Whippet tank preserved at Camp Borden in 1941. This British tank had fought on the Western Front during the Great War and was later brought to Canada and placed on display in Toronto before arriving at its current home at CFB Borden.

Whippet tank currently on display in the Base Borden Military Museum, CFB Borden, Ontario. (Author Photo)

No unit or divisional training was done by the regiment at Borden, it was mostly individual training such as driver and maintenance courses, tank gunnery courses, gas warfare, Non-Commissioned Officer (NCO) refresher training, and wireless (signals) courses. More recruits arrived from depots in Woodstock, Fredericton and Campbellton, New Brunswick, until they began to move by train to Debert, Nova Scotia in August 1941. They went on to Halifax for shipment overseas in October under the command of General Sansom.

Training in England

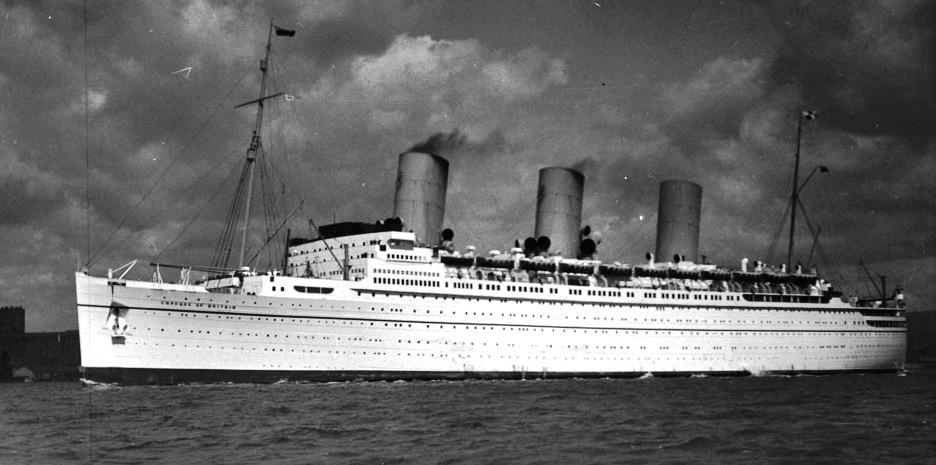

Canadian Pacific Liner “Empress of Britain”, 1932. (Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3394121)

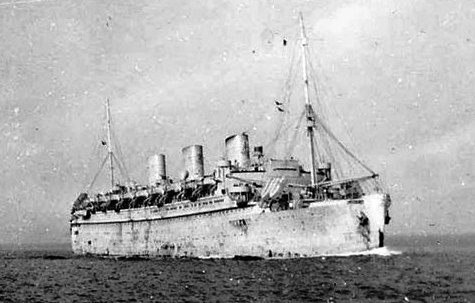

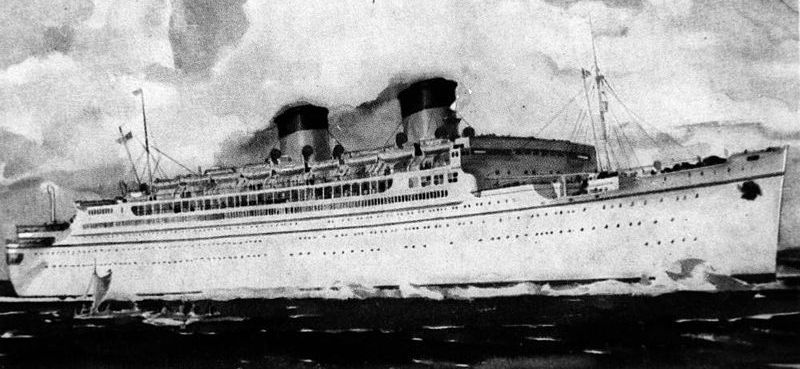

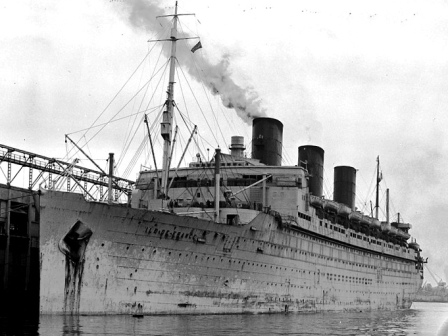

“Monarch of Bermuda“. The ships transported Hussars from Halifax to Liverpool in the UK in October 1941.

Harold’s friend William Craig indicated that he and Harold and a number of other 8th Hussars sailed overseas early in October 1941 on the ship “Empress of Britain.” According to Douglas How, another 647 of the 8th Hussars sailed to England on 9 October 1941, on another ship named “Monarch,” along with other Canadian units such as the Westminster Regiment (Motor); the Cape Breton Highlanders, and the British Columbia Dragoons. LCol Gamblin was the Officer Commanding (OC) the 8th Hussars at that time, and Major Black was the acting OC. They docked in Liverpool on the 15th of October, but the seas were too rough to disembark and they had to stay on-board for another two days. Following disembarkation, they traveled by convoy to their new quarters. On arrival, they were met by Canada’s Defence Minister, J.L. Ralston, who informed them, “your immediate job will be to buttress the defences of this island…(and) train to serve wherever and whenever you are needed.”[13]

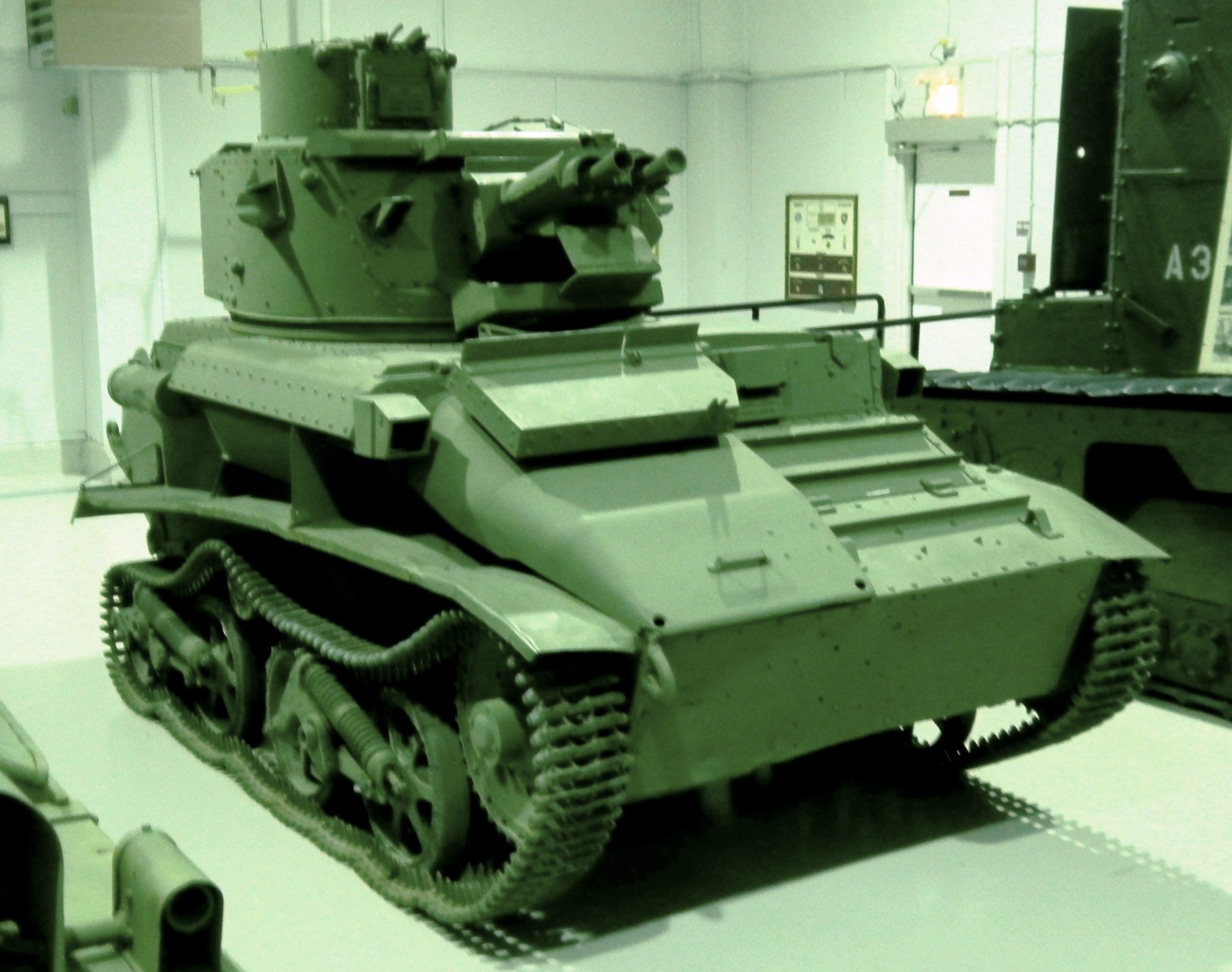

M3 Stuart Mk. I light tank of C Sqn, 5th Armoured Regiment (8th Princess Louise’s (New Brunswick) Hussars), 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade, 5th Canadian Armoured Division, Aldershot, England, May 1942. (Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3607530)

M5A1 General Stuart light tank, armed with a 37-mm turret mounted gun. The Stuart ran on high-octane aviation fuel. Its tracks did not come off easily and it was mechanically reliable as well as extremely manoeuvrable. British tank crews christened it the “Honey.” This tank is on display in the Base Borden Military Museum, CFB Borden, Ontario. (Author Photo)

The 8th Hussars went to Ogbourne St. George, an 800-year old village near Marlborough, England. Shortly afterwards, they were introduced to their first new tank, an M2A4, which arrived on the 11th of November 1941. It soon broke down. The M2A4 Stuart was a pre-war American standard tank that could cruise at 40 mph. It was easy to handle and permitted the driver ample vision through its wide glass windshield. It was armed with a 37mm cannon mounted in a turret. The M2A4 was replaced with two older model M3A1 Stuart light tanks.

While training in England, Canadian armoured crews also trained on the Vickers Mk VIB light tank. This tank is on display in the Base Borden Military Museum, CFB Borden, Ontario.

M3A General Lee tank armed with a 75-mm and a 37-mm cannon. This tank is on display in the Canadian War Museum, Ottawa, Ontario. (Author Photo)

Before the war was over the Hussars would work with ten different types of tanks. The next model of tank to arrive was the American-built M3A General Lee (dubbed the General Grant by the British) which worked mechanically well. The Lee’s fighting compartment left much to be desired, but it was armed with a 75-mm main gun mounted in a “sponson” on the right forward side of the tank. In addition, it had a 37-mm cannon mounted in a small top turret along with a coaxial machine-gun. Staghound scout cars were also brought in for training.

Staghound armoured reconnaissance vehicle on display in the Canadian War Museum, Ottawa, Ontario. (Author Photo)

The Staghound was used as an armoured reconnaissance vehicle by the 8th Hussars. Made by General Motors, it was used for a variety of functions such as raids, protection of road convoys and headquarters as well as on patrols to gather tactical intelligence. The vehicle was armed with one 37-mm cannon and two .303-inch machine-guns. It had a five-man crew and a top speed of 55 mph. Its maximum armour thickness was 1-¼ inches.[14]

Two months after the Hussars arrival in England the war began to expand. On 7 December 1941, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor with more than 350 carrier-based aircraft, striking successive blows against a large number of the American Navy’s ships which were anchored in Pearl Harbor. The Japanese struck a series of targets at Ford Island and at Kaneohe, and against the U.S. Army’s Hickam and Wheeler Air Fields. Within three hours after the first bombs had fallen on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese had sunk or badly damaged eight battleships of the United States Pacific Fleet and ten lesser ships. 2,335 American servicemen were killed and another 1,143 were wounded at the cost of 29 Japanese aircraft and their crews. The United States Army Air Force (USAAF) in Hawaii had more than a third of its aircraft destroyed and a great number of others damaged to varying degrees, leaving only about 80 aircraft still able to fly. More than 200 airmen were killed and another 300 were wounded.[15]

On the 8th of December 1941, the Japanese air forces attacked Hong Kong, Thailand, Malaya and the Philippines. The Allies declared war on Japan. On the 10th of December, the British battleship Prince of Wales and the battle cruiser Repulse were sunk by the Japanese off the coast of Malaya. On the 25th of December, the British and Canadians defending Hong Kong were forced to surrender to the Japanese. Over the next few months, the Japanese Armed Forces swept through the Pacific against little or no opposition. They carved out an Imperial empire that swallowed up the Malayan peninsula, the Netherlands East Indies (Dutch), the Philippines, and the Solomon and other islands of the central Pacific. On the 15th of February the British surrendered Singapore. The Allied forces surrendered in the Netherlands East Indies on the 9th of March. Wake Island was taken, Burma was lost and by mid-May 1942, the Japanese had overrun the Bataan peninsula and the island fortress of Corregidor, the last two American outposts on Luzon. The final surrender of US and Filipino forces in the Philippines came on the 6th of May 1941.[16] The Japanese had succeeded in capturing all of Burma, and in turn forced the American forces to withdraw to Australia and the British forces to withdraw into India, where they prepared to continue the fight.

In the Middle East, aircraft of the RAF’s Desert Air Force and the American 8th, 9th and 12th Air Forces carried out a number of missions against General Irwin Rommel’s Afrika Corps, in preparation for the invasion of North Africa under Operation Torch. With plans also being made for the invasion of Italy, Lieutenant General Dwight D. Eisenhower was appointed commander of Allied Force Headquarters in London.[17]

In January 1942, Canada’s Prime Minister Mackenzie-King made an announcement that a Canadian Army consisting of two corps would be created in England under the command of General McNaughton. The 4th Division in Canada was converted into an armoured division and another army tank brigade was to be raised.[18]

Throughout the winter of 1941 and 1942, German submarines had been sinking so many supply ships and fuel tankers in the Atlantic that the fuel being used by soldiers in England had to be rationed. This in turn cut down on the amount of training time available for the tank crews.

Canadian-built 32-ton Ram Mk. II tank armed with a six-pound gun. This tank is on display in the Base Borden Military Museum, CFB Borden, Ontario.

In April 1942 the 8th Hussars were posted to Aldershot where the training facilities were better. Shortly after their arrival the 8th Hussars were equipped with Canadian-built Ram tanks. The Ram provided the basic design for the American Sherman, and was the result of a combination of British, American and Canadian engineering ideas. Its all-cast hull and turret were a new departure, which greatly speeded up production. The wireless installation was identical with the later Sherman while the two-pounder gun in its turret was eventually replaced with a six-pounder. Weighing 32 tons, the Ram had a 400-hp radial engine and a top speed of 32 mph. Three models appeared in all, with the II and III both possessing the six-pounder gun and other modifications based on suggestions which the tankmen themselves forwarded to the production line in Canada.[19]

Canadian-built 32-ton Ram Mk. II tank armed with a six-pound gun. The secondary turret on the hull has been removed. This tank is on display in the Base Borden Military Museum, CFB Borden, Ontario.

King George VI and the Queen visit the 8th Hussars in Aldershot, England on the 24th of April 1942. They are inspecting an M3A General Lee tank. The King is standing on the left, accompanied by Lieutenant Colonel Gamblin and Major General Sansom.

The 8th Hussars were visited by General A.G.L. McNaughton and shortly afterwards on the 24th April 1942, the King and Queen arrived to inspect the Hussars. During the Hussars training in England, some of their staff members were briefed by Britain’s famed General Bernard Montgomery. In May LCol Gamblin handed over command to LCol George Robinson. Shortly afterwards the unit moved to Little Warren Camp.

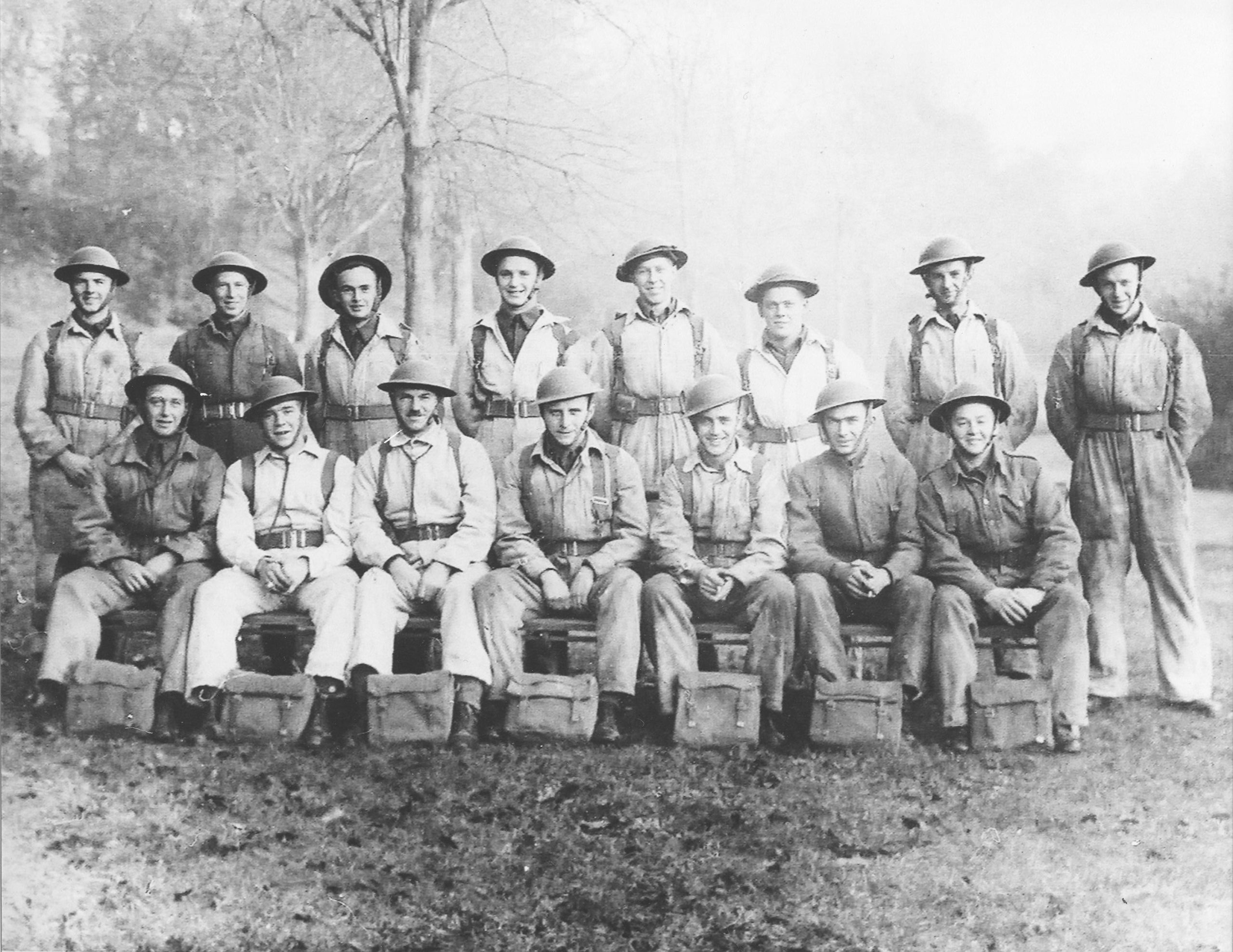

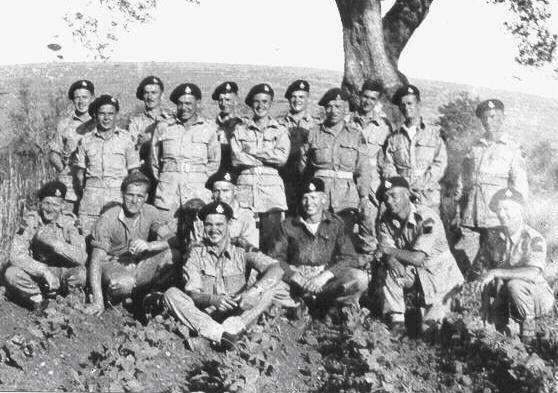

8th CH group training in England, ca. 1943.

Back Row: John Curran, Harold J. Skaarup, Joe Bradshaw, Ray Ogilvie, Gordon Carson, Boyd Linton, Joe Deveau, Brub Schriyer.

Front Row: Murray Brewer, Wilfred Barter, Sgt Major Stannix, Lt Hill, Don Cunningham, Danny McKasakill, Angus Henwood.

8th Canadian Hussars (Princess Louise’s), England 1942, three tank crews, two on leave. Back Row: John Curran, Teddy Burtch, Harold J. Skaarup, Hunter Dunn, Maven Logan, Doc McCallum. Middle five in a row: Sherman Allen, Danny McAskill, Darrel Yeomans, W.A. Chuck Fair, B.J. Cusack. Two in front: Lester Murphy and B.B. Damery.

B.B. Damery’s son wrote, “My dad was an 8th Canadian Hussar during the war. He was with the regiment all through Italy and up until the end of the war. He joined in Sussex and was originally from Chatham. Once the war was over and he came home, he ended up in the Royal Canadian Dragoons (RCD) as the Hussars were disbanded. When the regiment was reformed again in 1957, he was transferred from the RCD to the Hussars and remained with them until he retired in 1971. During that time we were posted to Gagetown, Iserlohn Germany, Petawawa and then back to Borden again. He never spoke much about the war although I have found out a great deal since he died in 1976. I know he was hit several times with 88s, once in Italy and again in Holland and was thought dead and shown his own grave marker at Corriano. It would be interesting to know if your uncle and my dad were ever crew mates. My dad was always in B squadron throughout the war, except for a period in early 1945 when they put the remnants of B Sqn with C Sqn because of loss of personal and equipment. Your uncle was hit during the push toward Corriano which is where my dad’s tank was first hit and everyone in his crew died except him, that is where there was a mix up because they had to withdraw. He hid in the village until they retook the position. Somehow he was given a grave along with his other crew members (the tank had burned and they just assumed everyone was in it). He didn’t realize what had happened and it wasn’t until he asked to be reassigned that his CO took him and showed him his own grave marker. His Lt. was William Spencer who went all thorough the war with him until he was killed on 14 April 1945 in Holland.” (Bill Damery, e-mail , 18 March 2018)

In June the war in the Pacific began to turn in favour of the allies when the Japanese Imperial Fleet lost four aircraft carriers, Akagi, Kaga, Soryu and Hiryu, and the heavy cruiser Mikuma, to American aircraft operating from the carriers USS Enterprise, Hornet and Yorktown. The American fleet lost the carrier USS Yorktown and the destroyer USS Hammann, in a great air and sea battle which took place near Midway Island.

Churchill tank similar to the type used by Canadians at Dieppe. This tank is on display at the Base Borden Military Museum, CFB Borden, Ontario. (Author Photo)

On the other side of the world, the Canadians carried out a nine-hour raid on the German occupied town of Dieppe, France on 19 August 1941 in Operation Jubilee. The raid was primarily carried out by 2nd Division troops, and the Canadians suffered very heavy losses. 5,000 Canadians, 2,000 British and a few American Rangers assaulted the German occupied coast of France at Dieppe. In the progress of the battle, 900 Canadians were killed and another 2000 captured, with and more than half of the attacking force being lost in the raid. The allies also lose 98 combat aircraft although 92 German aircraft were also shot down.

On the 23rd of October 1942, General Montgomery’s 8th Army launched its successful attack on the Axis forces at El Alamein in North Africa. This was followed in turn on the 8th of November, with the launching of a major invasion of North Africa, with Allied forces being landed in Algeria and French Morocco. The Germans in retaliation invaded the remaining unoccupied part of France on 13 November 1942.

Canada’s Defence Minister Ralston and his army staff conducted another visit to the 8th Hussars in the fall of 1942. This visit was followed by another move by the Hussars to Brighton-Hove on the South Coast. The Hussars continued to train on into 1943, with the size of the First Canadian Army being increased to five divisions in England.

Group photo of the men in 2 Troop, A Squadron, taken in front of a Ram tank, possibly taken at Crowboroughs, England, in the fall of 1942, Left to right, 1 unidentified, 2. Lt Hunter Dunn, 3. unidentified, 4. unidentified. The men are out in the tank training area.

Canadian-built 32-ton Ram Mk. II tank armed with a six-pound gun. The secondary turret on the hull has been removed. This tank is on display in the Canadian War Museum, Ottawa, Ontario. (Author Photo)

The Hussars by now had some 50 tanks, most of which were Canadian Rams with the six-pounder gun, while other equipment included some of the new US Shermans which were partly based on the Ram design. About this time the 4th and 5th Armoured Divisions were reorganized and placed together in the 2nd Corps, while the three Infantry Divisions were grouped together in the 1st Corps. Major-General Sansom was promoted to command the 2nd Corps and Brigadier C.R.S. Stein took command of the 5th Division.

Sherman III tank parked in front of the Officer’s Mess at CFB Borden, Ontario.

On the 7th of April 1943 the British 8th Army linked up with other allied troops in Tunisia and by the 12th of May had defeated the remaining Axis forces in North Africa. On the 22nd of May the Germans decided to withdraw their U-boats from the North Atlantic due to massive losses caused by Allied ships and aircraft, thereby reducing the danger to the critical supplies needed in England. On the 10th of July, Canada’s 1st Division invaded Sicily along with British and American troops. On the 22nd of July, Canadians captured the towns of Assoro and Leonforte. Mussolini resigned as Italy’s leader on the 25th of July and the Italian leadership was assumed by Marshal Pietro Badoglio. On the 28th of July Canadian troops captured the town of Agira, and the island of Sicily was completely conquered by the 17th of August. On the 3rd of September, British and Canadian troops landed at the foot of the Italian mainland and drove north. Not long afterwards, on the 8th of September 1943, Italy surrendered. The British and Americans landed at Salerno, Italy on the 9th of September, and on the 10th the Germans seized Rome. The Canadians took the Italian town of Campobasso on the 14th of October. On the 27th of October, a large number of Canadian troops boarded ships in Scotland bound for Italy. Their arrival raised the strength of the Canadian Forces in Italy to a full Corps.

On to Italy

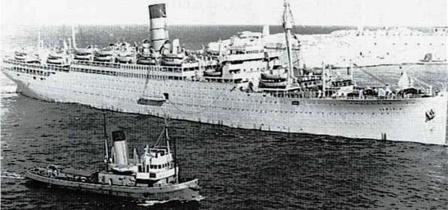

RMS Samaria, a Royal Navy troopship which carried the 8th Hussars to North Africa and Italy in 1943.

Launched in Nov 1920, the Samaria was frequently employed as a cruise ship. In September 1940 she took part in the evacuation of children from the UK to the US. In 1941 the ship was taken over by the Royal Navy and served as a troopship until 1948 when she was returned to Cunard and refitted for passenger service. Between 1948 and 1955 Samaria was assigned almost exclusively to the Canadian route with service to Montreal, Quebec and Halifax . In November 1955 she completed her last transatlantic crossing and was subsequently sold for scrapping, which was completed in Scotland in 1956.

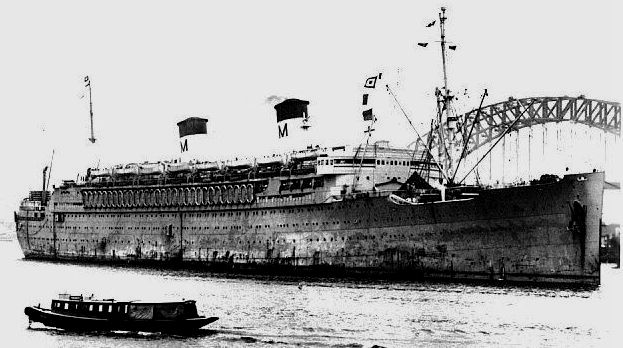

Troopship Monterey, which carried the 8th Hussars to North Africa and Italy in 1943. (State Library of Queensland, Australia Photo)

SS Monterey was launched on 10 October 1931. During the Second World War, she served as a fast troop carrier, often operating alone so she would not be slowed by formation navigation in a convoy. She was fitted with additional bunks, hammocks and facilities to accommodate up to 3,500 troops. One of her highlights was the rescue of 1,675 men from the torpedoed Santa Elena off Italy in 1943.

Troopship Santa Elena, bottom, sunk en route in 1943.

On the 13th of November 1943 the 8th Hussars boarded the liner Samaria along with 3000 5th Division troops, and sailed out of Liverpool bound for the Mediterranean shores of North Africa. Enroute, another ship named the Monterey carrying the 8th Hussars advance party, stopped to pick up survivors of the Santa Elena, another ship carrying 2000 people including the nurses and staff of No. 14 Canadian General Hospital, that had been sunk by German torpedo bombers. William Craig indicated that their convoy was attacked by at least half a dozen of these torpedo bombers, and that the men had to stay below deck during the attack.

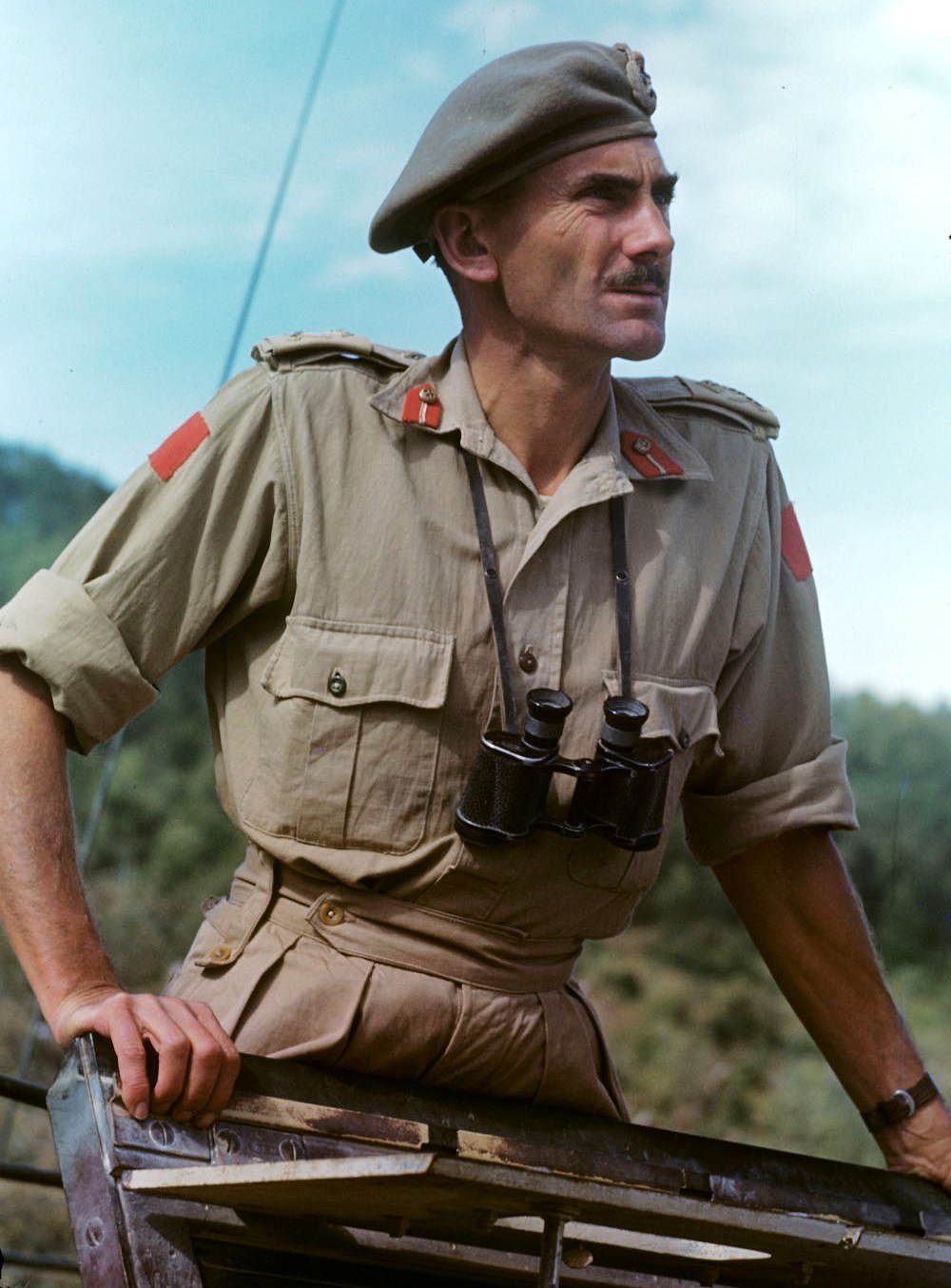

On 26 November 1943, the Samaria dropped anchor next to a French submarine in the city of Algiers, Algeria. Mr. Craig indicated that the Hussars remained here for 4 or 5 weeks, but then they eventually sailed on to the port of Naples, Italy. The Hussar’s advance party was inspected by Major-General Guy G. Simonds, who would later become one of Canada’s most famous army commanders.[20]

MGen Guy Simonds, Italy, 1943. (Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 4232760)

The British handed over badly worn out equipment that had survived the desert war for the Canadians to use for training, at Matera, Italy. They continued training at Matera for a month but as they did so, they were gradually re-equipped with “brand-new” Sherman Mark V tanks. The Sherman had a roomy turret and an improved driver’s compartment, and came with a Chrysler multi?bank engine that developed 450 hp. It was not as fast as the Ram, but had more power at low revs. Its 75mm gun was much better than any of its predecessors and the crews felt that for once the turret was efficient because it had been built around the gun. By the 19th of January 1944 there were 48 Shermans on strength, and the Canadians gradually got rid of the unserviceable British equipment. On the 28th of January, the regiment moved to the front.[21]

Harold’s A Squadron tank crew with their Sherman V medium tank in Italy. The early 30-ton Sherman had a five-man crew, a top speed of 29 mph and a cruising range of 150 miles. It mounted a 75-mm gun and carried two .30-calibre Browning machine-guns, and it was mechanically reliable.

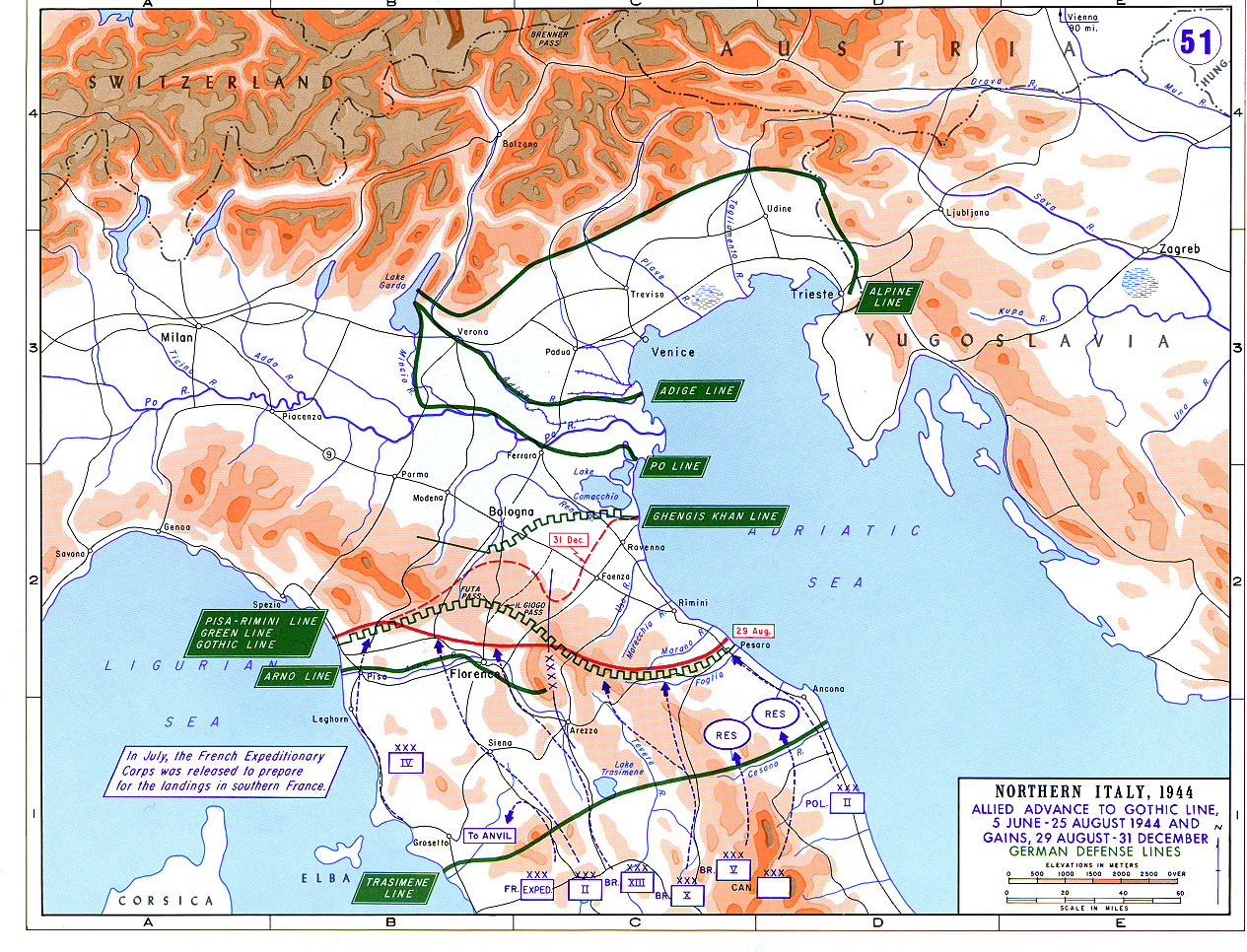

Map of the Advance to the Gothic Line, Northern Italy, 1944. (DND Photo)

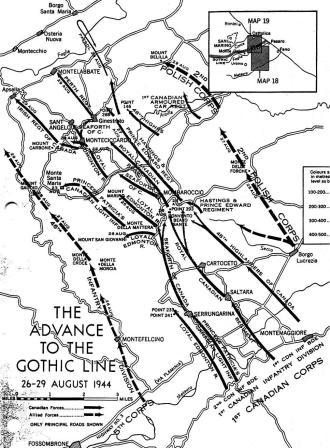

Map of the Advance to the Gothic Line between the 26th and the 29th of August 1944. Reproduced by the Army Survey Establishment, RCE. Compiled and drawn by the Historical Section, G.S.

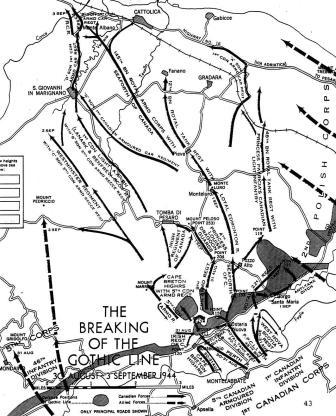

Map Showing how the Gothic Line was broken between the 30th of August and the 3rd of September 1944. Reproduced by the Army Survey Establishment, RCE. Compiled and drawn by the Historical Section, G.S.

To the Front

Two miles west of Ortona, the 8th Hussars were assigned to a counter-attack role. Bad weather and the Italian winter set in, and while he was on a visit, the Commander of the Canadian contingent in Italy Lieutenant-General Harry D.G. Crerar compared it to the Somme in 1916. The General’s 1st Canadian Corps at that time consisted of two Canadian Divisions and an independent tank brigade (the 1st Tank Brigade). Both the 1st Division and the 1st Tank Brigade had come through Sicily and the first prolonged and major Canadian action of the war, fighting for the Moro Valley and the coastal port of Ortona. The 1st Division had taken heavy casualties in the process.

General H.D.G. Crerar, CH, DB, DSO, KStJ, CD, PC. (Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 4233611)

The 8th Hussars received their baptism of fire in the wet fields west of Ortona, where they were well within range of the dominating German artillery. As a retaliation measure, the regiment’s tanks were set up to fire indirectly on the German positions. An intricate fire system was set up by an artillery survey section to bring fire down on a crossroads at Tollo, a village forward of Ortona. 48 tanks fired 15 rounds apiece onto the target, dropping 720 rounds into the heart of Tollo.[22] It is believed that the shoot set a precedent for armoured units. The Hussars withdrew as the Germans retaliated in turn by raining counter-battery fire on their previously occupied positions.

Sherman V tank armed with a 75-mm Gun, 5th Canadian Armour Regiment, 8th Princess Louise (New Brunswick) Hussars, Italy, 2 Mar 1944. (Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3599666)

The 5th Division moved south in March 1944 to an area near Castelnuovo, and soon came under the command of General Bert Hoffmeister.[23] The infantry battalions of the Division were the Irish Regiment of Canada, the Cape Breton Highlanders and the Perth Regiment. One squadron of Hussars was assigned to co-operate and eventually go into action with each of them. The tanks were themselves reinforced with additional armoured plates welded to their sides and armoured ammunition bins. Iron loops were also welded to their sides to aid in fixing camouflage.[24]

The regiment again moved in April, this time into the valley of Volturno in preparation for the spring battles. They were moved close to the Monastery of Monte Cassino overlooking the Rapido River, and then headed for the Liri Valley, which was a long, flat, rural corridor flanked by parallel ranges of mountains. Monte Cassino was the key to the valley, and the Germans had built two strong defensive lines across it, the Gustav Line based on the Rapido River, and the Hitler Line some nine miles long and heavily fortified.

The battle began on the 11th May 1944, with the 5th Division (including the 8th Hussars) in reserve. The allies breached the Gustav Line and reached the Hitler Line at great cost. The Hussars crossed the Rapido in their Shermans and entered the Liri Valley. The 1st Division was to breach the Hitler Line and the 5th Division’s orders were to pass through, establish a bridgehead across the Melfa River a few miles on, and then exploit towards the town of Ceprano. In essence the Hussars were in reserve for the first stages of the breakout, then they were to punch out of the bridgehead across the Melfa, establish a firm base 3,000 yards beyond the river and, if possible, exploit towards Ceprano. Meanwhile the German gunners dropped tons of high explosive shells on the 8th Hussars bivouac area for several days. The German six-barrelled mortar was particularly effective, in conjunction with 75-mm, 105-mm and 155-mm shells used against the Canadians.

German 15-cm Nebelwerfer 41. This multiple rocket launcher (MRL) is on display in the Canadian War Museum, Ottawa, Ontario. (Author Photo)

As the 1st Division proceeded to punch through the German lines, the 5th Division moved into the hole they made, putting the Hussars on the offensive on the 24th of May, 1944. The tanks inched ahead through heavy traffic over which a continuous haze of Italian dust hung in the air. As the Germans withdrew along Highway Six which was a vital paved road out of Cassino, the Hussars were ordered to cut off their retreat. During the ensuing firefight, one of the Hussars “Honey” recce tanks was blown up by a prepared charge with one man being killed and two others wounded. In return, the unit killed or captured some 30 Germans. Three tanks were trapped in gullies and could not extricate themselves as the Regiment prepared to disengage and move into a defensive harbour for the night. The Germans shelled the Hussars harbour as the men were ordered to dig in. One of their shells struck a Hussar tank just as it came into the harbour, killing the driver and injuring another crew-member who later died from his wounds. (This would be a common pattern, and is similar to the attack that took Harold out of the war). The rest of the Regiment came through its first fight intact.[25]

That same night, Major John Keefer Mahoney of the New Westminster Regiment (Motor) won the Victoria Cross fighting and holding a bridgehead on the far side of the Melfa River with a handful of Canadians. A company of his regiment had received orders to establish the initial bridgehead across the Melfa River, and Major Mahoney had personally led his company down to and across the river under heavy enemy fire. From 1530 hours the company held its position in the face of enemy fire and counter-attacks until 2030 hours, when the remaining Canadian companies and their supporting weapons were able to cross. The Germans worked furiously to keep Mahoney’s company under constant fire. Major Mahoney was wounded in the head and twice in the leg early on in the action, but he steadfastly refused medical aid and continued to direct the defence. He was decorated in the field by King George VI on the 31st of July 1944. The King had been traveling incognito as “General Collingwood,” at the time, and was reviewing Canadian troops near Raviscanina in the Volturon Valley.[26]

The next phase of the Canadian attack in Italy came at the end of May, with the enlargement of the bridgehead beyond the Melfa River and the drive to Ceprano. The Hussars were formed into a battle group, coming under the command of an infantry battalion, the Cape Breton Highlanders. While driving up to the Melfa River the Germans shelled the battle group heavily. The German artillery, mortars, machine guns and rifles maintained an incessantly heavy and continuous fire, while the ground was churned up and cratered by numerous devastating and deadly explosions. Witnesses recalled seeing the bodies of many dead soldiers and a number of destroyed German tanks littering the landscape. Nearby there was a string of allied tanks that had been picked off, one after another by the terribly accurate fire from a German 88-mm anti-tank gun somewhere on the far side of the river. The men also recall watching an artillery spotter plane being blown out of the sky by enemy fire, with the wreckage landing on a scout car.[27]

Across the river stood a high bluff, with the only route up being a donkey track to the right of the Hussars zone of attack. Engineers tried to improve the track with bulldozers. The Hussars edged into the river and headed for the bulldozed track as German shells slammed against their tanks. A carrier-towed anti-tank gun blocked off the route until a Hussar forced the driver to get it out of the way. Once across the track-way, two of the Hussar’s tank troops spread out into battle formation, accompanied by the infantrymen of the Cape Breton Highlanders (CBH). The Highlanders were strung out in a line and walked warily ahead of the Shermans. At about 5 PM a wall of concentrated anti-tank fire opened up on the tanks and at the same time, many of the CBH infantry were hit. There was no cover, and no place to go but forward, so the two tank troops drove on, firing their 75-mm guns as fast as they could. They fired at random because they couldn’t spot the enemy guns. One after another, four of the Hussar’s tanks were shot up and burned as the Canadian crews scrambled to get out.[28]

One tank crew was hit and while their vehicle was burning they observed a second shell go in one side and out the other as though its steel were made of butter. More Hussars were hit, but the other tanks kept up a steady fire. With exploding shells and burning tanks the field beyond the Melfa was turned into a fiery hell. The tank crews were forced to scatter as diving and dodging infantrymen climbed over the dead and dying. The surviving tank crews found themselves strangely insulated from much of what was going on outside their steel-hulled compartments. Their earphones crackled with orders or with incoherent word pictures that left the soldier with little real idea of what was happening and less to see through their tiny viewing apertures.[29]

The battle the squadron had fought had lasted only 15 minutes. When the Hussars rolled over the German positions, they found that they had knocked out three 75-mm guns and one self-propelled anti-tank gun. Most of the tanks of C Squadron however, had been reduced to burning hulks, although only one trooper had been killed and three wounded (one of whom later died). The Hussars settled down for a long sleepless night.[30]

German Panther V in Italy, 31 Dec 1943. (Bundesarchiv Bild 101I-478-2164-39)

Another attack was launched at 7 hours over very difficult ground which was full of gullies and streams and clumps of trees that were treacherous to tanks. The Germans fought piecemeal in small pockets of resistance trying to cover their main withdrawal. The engineers worked hard to clear the obstacles and mines, and to restore crossing sites over the rivers, while the artillery Forward Observation Officers (FOOs) called fire down on German positions. By 5 hours, B Squadron was in thick, tangled country and the infantry were caught up in a skirmish. The tanks were moving ahead to take on mortars and machine-guns when suddenly they were attacked by anti-tank fire from two sides. A German Panther V tank armed with a 75-mm gun shot up one of the Hussar’s tanks, but it returned fire, brewing up the huge Panther tank. Another Hussar tank was knocked out shortly afterwards.[31]

German Panther V tank. The Panther mounted a 75-mm gun and carried two 7.92-mm machine-guns. It had a top speed of 30 mph and could outfight any Allied tank in a one-on-one encounter. The Canadian Sherman mounted with a less powerful 75-mm M3 L/40 gun could only take out the Panther by hitting it in the side. Later Sherman models armed with the 17-pounder gun were much more deadly in the tank on tank encounters. This Panther, previously on display at CFB Borden for many years, has been restored and is on display in the Canadian War Museum, Ottawa. (Author Photo)

On the 27th of May the Hussars reached the Liri River, but couldn’t find a crossing site. Pausing to rest, many of the Hussars were caught in the open by German artillery fire, five were killed and eight more wounded. The Germans withdrew and the units crossed the river. Eight more Shermans were brought in to replace their losses. As the advance continued the going was slow and the ground difficult for the Hussars to accomplish much on, before they reached Ceccano. North of Ceccano, there were enough road craters, minefields and snipers to bring everything to a halt. The tanks were halted after eight days of action, having covered some 24 miles of German defended territory.[32]

Group photo with Harold’s A Squadron tank crew in Italy. Harold is in the centre, holding a pistol with his tank troop horsing around.

Four days after the Regiment left the line, Rome fell to the Allies on the 4th of June. The event was largely overshadowed two days later by the 6th of June Allied invasion of Normandy, which opened the campaign in Western Europe. More than 30,000 Canadian soldiers, sailors and airmen took part in the D-day invasion. The 8th Hussars rested and prepared to move, following more training exercises. In August they prepared to take on the Gothic Line. The Hussars moved to Cerreto and then to Castel Raimondo, and then on to Iesi.

This time the battle plan called for both the 5th Division (now equipped with a second infantry brigade) and the 1st Division to breach the line. The Hussars were the key element in the attack. The plan was to cross the valley, to seize the heights and then go on. The ground however was not easy. The gravel bed of the Foglia River was less of a problem than the low-lying meadows. The valley had been cleared of trees and buildings and sown with minefields and anti-tank ditches some 14 feet across in a zig-zag pattern in front of the road through most of the Canadian sector. The slopes beyond were planted with numerous machine-gun posts, many of them encased in concrete and the majority connected by covered passages to deep dug-outs. Wire obstacles more formidable than any that the Canadians had yet encountered in Italy surrounded these positions and, behind them, more wire ran in a broad belt along the whole front. This in turn was covered by fire from another zone of mutually supporting pillboxes and emplacements, forming an interlaced killing-ground that had been proportioned off with geometric skill. Anti-tank guns, dug-in flame-throwers, and Panther tank turrets added to the formidable blocks put in the path of the Canadian assault forces.[34]

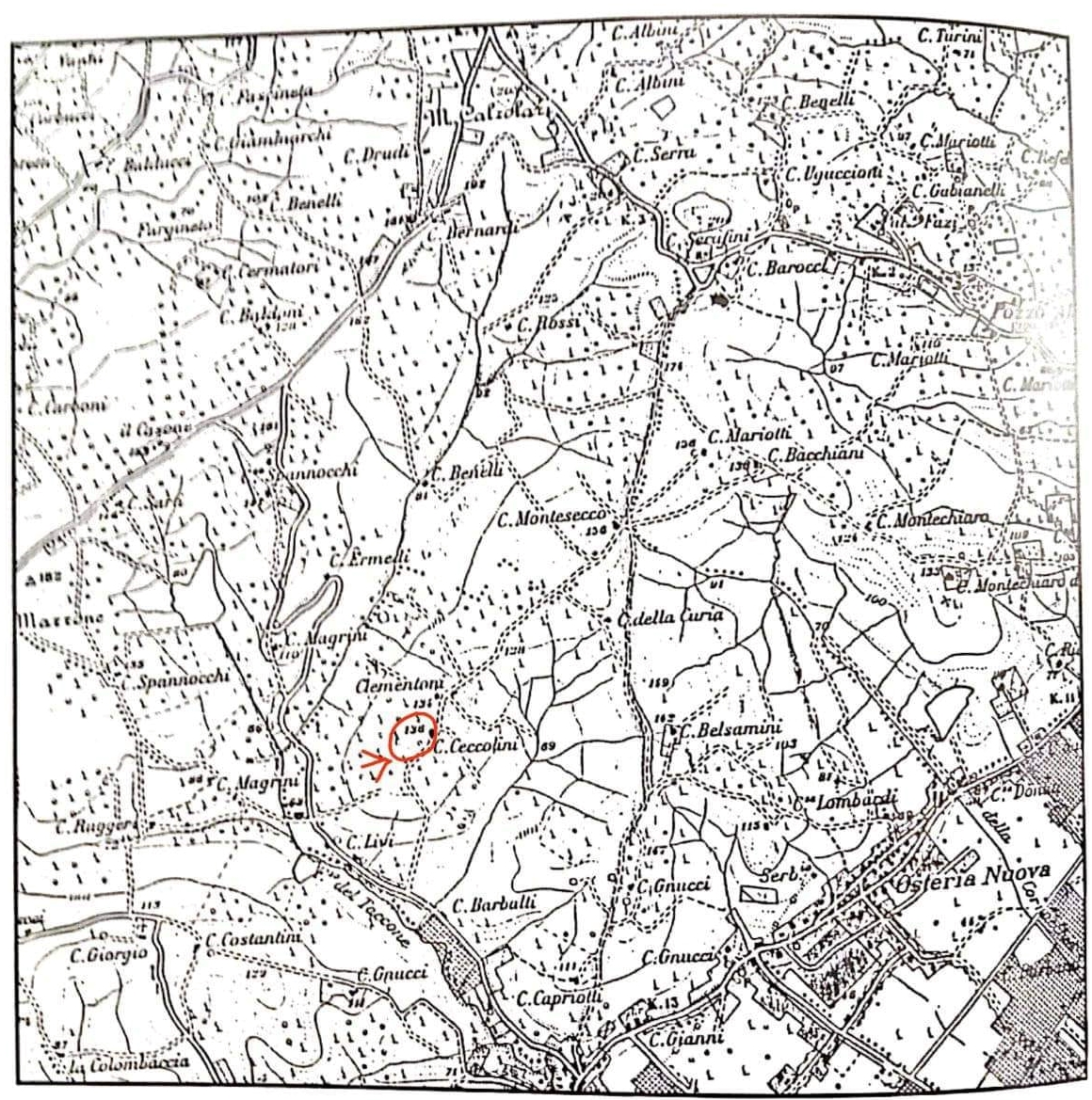

Nearby, the town of Montecchio lay within the compass of the claws of two hills, the Pesaro lateral and the bulky Tomba di Pesaro-Monte Luro hill mass. Point 111 was the termination of a long ridge coming down from the northeast behind Osteria Nuova, and Point 120 was an abrupt knoll which crowded in upon the town from the west. Montecchio would become Harold’s last resting place.

The Cape Breton Highlanders and B Squadron were to take Point 120, the Perth Regiment and A Squadron Point 111, half a mile to the right and within easy sight. Then the Irish and C Squadron were to seize the high ground around Tomba di Pesaro. C Squadron fired the Regiment’s first volley of 120 rounds by four tanks into the Montecchio target area by indirect fire. As the Hussars advanced the Germans manned the rocky crag known as Point 120, and the battle developed into a hard fight. The Highlanders were thrown back three times. Mines blew up many of the supporting vehicles, while much of the supporting artillery fire passed over the German positions. The assault force had to withdraw.[35]

At Point 111 A Squadron met the Perths and deployed on the far bank of the Foglia with 18 tanks and accompanying infantry. German artillery and machine-gun fire blasted the attacking forces, although counter-battery fire kept the Canadian casualties down until they got onto the hill. Here the German mortars and shells took a heavy toll of the infantry and one of the Hussar troops.[36]

The plan was changed to swing in an arc and hook behind Montecchio and take Point 120 from the rear. C Squadron made the attack after splitting into two groups from Point 111. B Squadron opened fire on Montecchio from down in the valley, while A Squadron fired from Point 111. Artillery joined in as attacking tanks closed with the fortress. A German self-propelled gun kept firing on them until two tanks destroyed it simultaneously. Firing over open sights, the tanks continued the advance along with the Irish. The tanks destroyed two German guns but lost six of their own number when their tank-tracks came off on the steep slopes. The Irish, incredibly, suffered only one casualty. 130 German prisoners were taken and many more became casualties. The bastion of Montecchio had fallen to a well-coordinated attack from the rear.[37]

A Squadron had moved from Point 111 to try for higher ground, but without infantry support. A German anti-tank gun destroyed one of the Hussar’s tanks as the others attacked it. Another Hussar tank was blown up as the gun was destroyed. German infantry closed to attack the evacuating tank crews and casualties mounted on both sides. From then on it was a duel between the Shermans lumbering uphill over rough ground and the interlocking German anti-tank positions. The Hussars’ immediate objective was a crest known as Point 136. One tank was knocked out on the way up as the German fire intensified with mortars and other weapons concentrated on the tanks, stopping them in their tracks. The Hussars called in supporting artillery fire, then the tanks resumed the attack. Another tank lurched back and rolled over after being hit by a German 88mm anti-tank shell, although the crew got out. Without infantry, the tanks could not seize the crest.[38]

Another tank was badly damaged and by now German fire had destroyed ten of the Hussars’ tanks, leaving nine to fight a losing battle. One tank was sent down the hill to get reinforcements and another broke down with engine trouble, reducing the group to seven. These were reorganized into a defensive position in anticipation of a German counter-attack. During the battle, some of the tanks had exhausted three times their full stocks of ammunition. The A-1 echelon had its hands full just keeping them supplied, with one of its officers (Captain Jack Boyer) winning the military cross in the process.[39] He kept well forward (within 400 yards of the fighting tanks) and had quantities of ammunition and fuel dumped close by. He then arranged for the tanks to drop back a troop at a time to positions out of the direct line of German fire, where fuel and shells were delivered to them by the light tanks of Recce Troop.[40]

Point 136 in red near Montecchio.

Above the dump the tanks on Point 136 waited for a counter-attack that never came. Instead the Perths worked their way up the hill at 1900 hours to take over the position, and for a brief period the tanks stayed with them. The seven remaining tanks eventually went on to Point 111 for the night. Although A Squadron had lost ten men (four killed and six wounded), it had knocked out one German tank, two anti-tank guns and killed 25 Germans. [41]

B Squadron came up out of the valley and “laagered” (moved into a safe harbour) well below the crest, while sporadic firing and heavy shelling continued throughout the night. Orders came for the Highlanders to attack through their positions towards Monte Marrone, and they managed to scale the heights without significant loss. Scouts came back to lead the tanks up at dawn. At this stage the Canadian attack had reached to within 1,200 yards of the twin dominating peaks of Monte Luro and Point 253, roughly a mile apart. On a spur of Point 253, astride the Gothic Line, was the town of Tomba di Pesaro.[42]

The tanks moved up about 0600 hours and sat in behind the hill most of the day under heavy shell, mortar and anti-tank fire. Major Keirstead indicates that as white sheets were waving from some of the houses he sent Cpl Sheppard in to investigate. As the Hussars fired on the town, German fire was returned and two more Hussar tanks began to burn. Heavy fighting against German infantry and anti-tank guns continued, with more Hussar tanks being knocked out. The Germans however, began to surrender and many prisoners were taken.[43]

One Last Salvo

German 8.8 cm PaK 43, Lisle, Ontario. (Balcer Photo)

The battle continued for most of the day, but at some time between 0915 and 1030 hours on the morning of the 31st of August, Harold’s tank (a Sherman Mark V nick-named “Acorn”) was hit by a shell fired from a German 88-mm anti-tank gun. The shot entered the side of the tank just under the turret and took off both of Harold’s feet. All four of the tank’s crew-members bailed out of the burning tank, but just as they did so, a salvo of German mortar shells (possibly from a six-barrelled “Nebelwerfer” mortar) landed in the midst of Harold’s tank crew. Already badly injured, Harold was hit again, this time with shrapnel fragments entering his chest. He was evacuated to a field hospital in the rear area, but died from his wounds at the age of 24 on the 6th of September 1944.[44]

I spoke with my uncle, Captain (retired) Ronald F. Hawkins, MM, who was engaged in the same battle that Harold’s unit took part in. Ronald served in the Italian campaign with the Cape Breton Highlanders, part of the 11th Infantry Brigade which was also part of the 5th Armoured Division. He fought against the German “Panzer Grenadiers” in battles to the north of Ortona on Fendo Ridge and across the Arelli River. He later became the unit’s mortar platoon sergeant and after a time the quarter-master of B Company CBH. After 15 months of fighting in the rugged mountains and river valleys of Italy, Sergeant Hawkins moved with the Canadian Corps to France and then on to Belgium and Holland. As the Sergeant-Major of C Company, he was in the front line at Delfzijl, the last town liberated by the Highlanders when the war ended. For his service in the war, he was awarded the Military Medal for gallantry. As mentioned, Ronald participated in the same battle that Harold was wounded in, and although he didn’t know him at the time, he provided the following information.

He particularly remembers the ground from Montecchio, and the Foglia River to the Coriano Ridge and town. They were pinned down as a result of a pre-attack plan that involved five days of shelling at Coriano, one of their toughest spots. His whole unit left Montecchio, going up through some rolling hills and then stopped. At that point, they took up defensive positions but then stood down. He was promoted to staff sergeant quarter-master the following night. They didn’t see the 8th NBH, which he knew were from New Brunswick, but understood that they were moving around the CBH. Sergeant Hawkins passed a tank in a cut (sunken road) where he spoke to Billy Craig, a driver of one of the 8th NBH vehicles. There was a tank up the hill in a rock cut nearby. This was Harold’s. Billy Craig told him that a shell hit the tank while they were changing crews. There were men standing on the tank and some standing on the ground. Hawkins and his platoon didn’t go near as they were to be moving on. Years later, Hawkins met Billy Craig again at the legion in Woodstock and introduced him to Harold’s father, Frederick Skaarup.[45]

William Craig survived and in a conversation I had with him he indicated that he and Harold had joined the Army together in Fredericton in April 1941. He recalls that five men at a time put their hands on the Bible to be sworn in. He remembers a man named Sorenson from Salmonhurst, Charlie Brown and another man from Canterbury, himself and Harold being in one of the groups of five. William stated that they were sent to Fredericton for three weeks of basic training, and were then shipped off to Camp Borden by train. He confirmed that while there, they were only trained on Whippet tanks (in this case, most likely the American-built M1917 tanks). They both went home on leave to New Brunswick in September 1941, and then went back to Borden. From there they took the train to Halifax and sailed to England on the Monarch of Bermuda, docking at Liverpool.[46] From there they went on to Ogbourne St. George.

Heinkel He 111H6-LF5b torpedo bomber. (Luftwaffe Photo)

Eventually they sailed to the Mediterranean, and while enroute William remembers their convoy being attacked by a half dozen German torpedo bombers. His ship was one of a number that stopped to pick up survivors from one of the other convoy ships that had been torpedoed and sunk. He remembered that the Germans hit one of the escorting destroyers, which ran itself aground on the sandy shores of North Africa. They docked in Algiers some seven miles up the coast from Tangier, where they were kept for 4 or 5 weeks. They then moved on to Italy, to a site near Mount Vesuvius. Once they had landed, they were transported up to the town of Matera, where they received brand new Sherman Mark V tanks armed with a 75-mm gun. Mr. Craig recalls that they were carrying about 100 rounds of mixed armour-piercing (AP), high-explosive (HE), air-burst (AB) and smoke-shell (smk) on or in their tank. Their personal equipment (along with spare rounds) was kept under a tarp on the back of the tank.

As for the battle on the morning of the 31st of August, William recalls seeing Harold’s tank being hit as recorded above. William’s tank “Aroostick” was also hit that morning, with an anti-tank round going through his driver’s compartment and tearing off the driver’s legs. Although the crew all bailed out, William’s driver died within a few hours. With the battle continuing, the survivors had to make their way back to rear area on their own under fire. He recalls seeing a third tank in action near them named “Abitibi.” As recorded in the 8th Hussars War Diary, A Squadron had lost nine tanks that morning in just this one battle.[47]

Later, an Anglican Minister from Centreville, New Brunswick, delivered the telegram to the Skaarup family. Harold’s mother Anne also received two letters from the Department of National Defence, and these are reproduced verbatim here.

Quote No. H.Q. 405-S-26,760 (Records C)

Department of National Defence

Army

Ottawa, Canada

19 September 1944

Mrs. Anne Skaarup,

R.R. #3,

Centreville,

Carleton County,

New Brunswick

Dear Mrs. Skaarup:

With reference to the regretted death of your son G753 Lance Corporal Harold Jorgen Skaarup, I am directed to inform you that official information has now been received from Canadian Military Headquarters Overseas, advising that he was wounded in action on the 31st of August and became dangerously ill, suffering from a shell fragment wound with a traumatic amputation of both feet, and chest wounds, which caused his death on the 6th September 1944.

Please accept my sincere and heartfelt sympathy for the irreparable loss you have suffered.

Yours sincerely,

(C.L. Laurin) Colonel

Director of Records

For the Adjutant-General

Office of the Adjutant-General

Department of National Defence

Army

Ottawa, Canada

29th September, 1944

Mrs. Anne Skaarup,

R.R. #3, Centreville,

Carleton County, N.B.

Dear Mrs. Skaarup:

It was with deep regret that I learned of the death of your son, G753 Lance Corporal Harold Jorgen Skaarup, who gave his life in the service of his Country in the Mediterranean Theatre of War, on the 6th day of September, 1944.

From the official information we have received, your son died as the result of wounds received in action against the enemy. You may be assured that any additional information received will be communicated to you without delay.

The Minister of National Defence and the Members of the Army Council have asked me to express to you and your family their sincere sympathy in your bereavement.

We pay tribute to the sacrifice he so bravely made.

Yours sincerely,

(H.F.G. Letson),

Major-General,

Adjutant-General

In May 1960 Harold’s brother Aage and his wife Beatrice and her Mother, Myrtle Estabrook, visited Harold’s gravesite at the Canadian War Cemetery in Montecchio. A few years later his brother Carl and family visited the site. Hal and Faye Skaarup also came to visit the gravesite on the 22nd of May of 1983. We signed the visitors register, and noted that there were many other Regiments familiar to us there, including the 8th Princess Louise (NB) Hussars, the Carleton and York Regiment (NB), the Loyal Edmonton Regiment, the North Nova Scotia Highlanders, the West Nova Regiment, the Cape Breton Highlander’s, the 48th Highlander’s, the RCR and many more. We also visited one of the largest of the Canadian grave-sites in Italy near the village of Corriano on a calm, warm evening, quiet and peaceful, just as the sunset. All the Canadian war graves in Italy are well cared for, and they are important places that should be visited by those of us who live in the world these men and women fought to preserve.

Harold J. Skaarup’s War grave, Montecchio War Cemetery, Italy, IT.28, Row III, B.7.

The Montecchio War Cemetery in Italy lies in the locality of Montecchio in the Commune of Montelabbate (Province of Pesaro). It stands on rising ground just north of the main road from Pesaro to Urbino, about 12 kilometres west of Pesaro. Should you wish to visit the site one day, take the SS 423 road from Pesaro to Urbino, following the signs for Montecchio. Just before entering the town, the cemetery will be seen on the right hand side of the road.

Montecchio lies near the Eastern end of the strong German defensive position known as the Gothic Line. The anti-tank ditch of this defensive system used to run through the valley immediately below the cemetery. Montecchio village was practically razed to the ground for the purposes of defence during the war, and much damage was done in the surrounding country. The site was selected by the Canadian Corps for burials during the fighting to break into the Gothic Line in the autumn of 1944. An additional plot was added later for graves brought in from the surrounding country. There are now 582, 1939-45 war casualties commemorated in this site. Of these, 4 are unidentified.[48]

Eric Sorensen and Harold J. Skaarup, wearing the Hussars tropical uniform in Italy, possibly the summer of 1944.

The Hussars Move On

Soldier, possibly a Cape Breton Highlander, examining the treads of a Sherman V tank, possibly of “B” Squadron, 8th Princess Louise’s (New Brunswick) Hussars, during the assault on the Gothic Line, Italy, ca. 31 August 1944. (Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3512561)

While B Squadron was recovering, the final attack went in at night and by the afternoon of the next day Point 253 to the right of Tomba di Pesaro had fallen. The Hussars’ C Squadron and the Irish were ordered forward into the positions on the crest to strike at the town itself.[49]

As the Squadron assembled a hidden group of Germans opened up on them and a large number of Hussars were killed or wounded. When the firefight was over, seventy Germans surrendered and were handed over to the Irish by the Hussars. Only ten tanks succeeded in fighting their way successfully to the top of the hill, the slopes throwing many off their tracks. These ten tanks reformed on the crest and moved off by 1700 hours to seize two more features to set the stage for the final assault on the town itself. The Irish climbed up on the back of the tanks as five Shermans charged across the hill and the remainder fired in support. The Germans had withdrawn however, and by 2000 hours Tomba di Pesaro was solidly in Canadian hands.[50]

Monte Luro was soon captured by the men of the 1st Canadian Division under the command of Major General Chris Vokes, and with these victories, Monte Marrone, Point 253 and Tomba di Pesaro and the heights were won. The commander of the 1st Canadian Corps, Lieutenant General E.L.M. Burns reported to Lieutenant General Oliver Leese of Britain’s 30th Corps that the Gothic Line in the Adriatic sector was completely broken, and that the 1st Canadian Corps was advancing to the river Conca.[51]

The 8th Hussars had been the key armoured element in a divisional attack, losing 14 men in the process. Major General B.M. Hoffmeister’s 5th Armoured Division had succeeded in crashing through the formidable Gothic Line. The Canadian Corps now stood ready to drive on to Rimini and into the plains beyond. The Hussars refuelled but only partially re-equipped, began to move again on the 3rd of September to continue the pursuit against the Germans.

In time, after more terrible battles and many casualties, the Canadians would capture Coriano Ridge just south of Rimini on the 13th of September. They would win San Fortunato Ridge on the 20th of September, as German forces fought desperately to keep them out of the Po Valley. The war in Italy became a series of assaults from one river to another in slow vicious fighting up through the Po Valley. On the 22nd of October, Private E.A. “Smoky” Smith won the Victoria Cross on the Savio River crossing in Italy. The Canadians took Ravenna on the 4th of December, followed by Mezzano. As they moved into the New Year, the Regiment conducted an attack on Sant’ Alberto until they were pulled out of the line between the 11th and 14th of January 1945. By now 42 Hussars lay buried in Italy.[52]

A group of the 8th Hussars in the south of Italy, fall 1944. In the rear rank from left to right, #1, 2 and 3 are unknown, #4 is Elmer Devoe F32035, #5 is Jack F. Stewart G160, #6 is George A. Bridgen SG334, and #7 is Sgt Archie Stevens G146.

In the second rank, #1 is Charles F. “Muscles” McGrattan G105, #2 is William F. “Horn” Bell G21, #3 is Joseph A. Bradshaw G49, and #4 is William J. Preston G190.

In the third rank seated #1 is Lt George G. Pitt, #2 is unknown, #3 is Lt Waldo E.Tulk, #4, 5 and 6 are unknown. Seated in front is Capt Douglas E. Lewis.

France and Germany

In February 1945, the Hussars were moved again, this time to Leghorn in the south of Italy, to prepare for the move to Northwest Europe. They sailed for Marseilles, France, with most of the unit arriving by the 23rd of February. In convoys they rolled north through Lyons and the valley of the Rhone and on to Cambrai and Valenciennes of First War fame, until arriving at Roulers in Belgium on the 1st of March, some 1,100 miles from the front they had left three weeks before. By the 20th of March, a vast pincers movement by American, British and Canadian forces had broken through the renowned Siegfried Line and won Europe west of the Rhine River. Three days later the assault across the historic river itself had begun.

Sherman tank armed with a 75-mm Gun, 5th Canadian Armour Regiment, 8th Princess Louise (New Brunswick) Hussars, Putten, Netherlands, 18 Apr 1945. Churchill tank tracks attached to this tank as add-on armour. (Capt Jack Smith Photo, Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3396461)

Sherman Ic Hybrid Firefly tank armed with a 17-pounder Gun, 8th Princess Louise (New Brunswick) Hussars, 5th Canadian Armour Regiment, Putten, Netherlands, 18 Apr 1945. Firefly crews attempted to disguise the length of the 17-pounder gun barrel to confuse German anti-tank gunners by fitting a false muzzle brake half-way up the barrel and painting the forward portion in a counter-shaded pattern. (Capt Jack Smith, Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3396461)

The Hussars left Roulers on the 1st of April and moved to Nijmegen, Holland, where the war was in its final stages. As of the 15th of March, elements of the 1st Corps had been committed to action west of the Rhine. For the first time, Canada had two corps serving side by side on the battlefield. Of greater significance was the fact that the 1st Canadian Army now had enough Canadian formations (five divisions, two tank brigades and ancillary forces) to be a real army. The 8th Hussars joined this force under the 5th Division, and were in action on the 3rd of April.

The 5th Armoured (or as the troopers called it, “Hoffy’s Mighty Maroon Machine,” after their commander, MGen. Bert Hoffmeister) came to North-West Europe in the spring of 1945 to join 2nd Canadian Corps. The units of 1st and 2nd Corps were thus reunited to form the largest active army ever commanded by a Canadian, Lt. Gen. Harry D.G. Crerar.

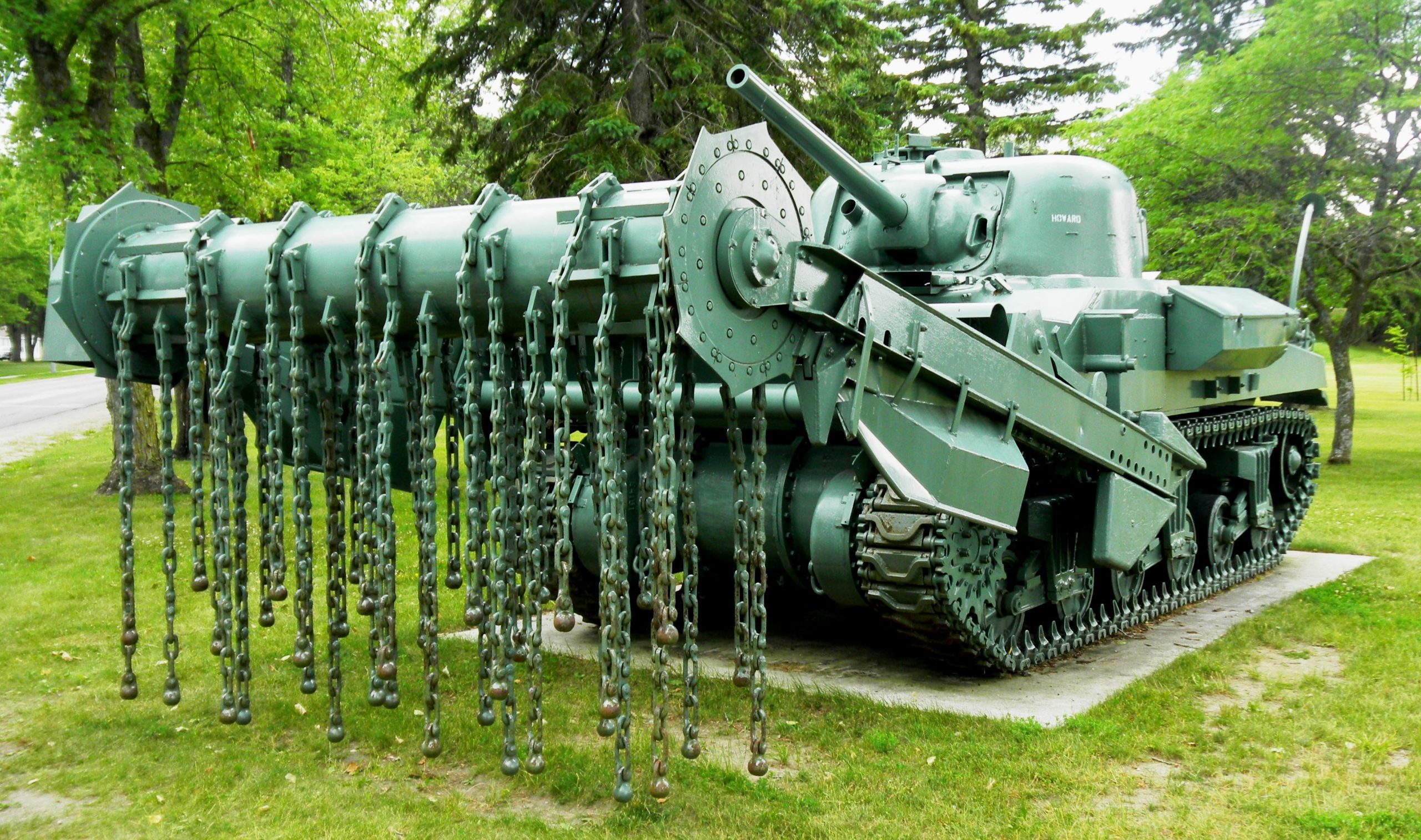

M4A4(75) Sherman Crab Mk. II mine flail tank with 75mm gun, built by Chrysler (Serial No. 5072) Reg. No. 3056882, DV. MGen Worthington Memorial Park, CFB Borden Military Museum, Ontario. Flail tanks were used to clear minefields in Normandy and Northwest Europe. (Author Photos)