Artillery of New France in Canada

“By each gun a loaded brand, in a bold determined hand.”[1]

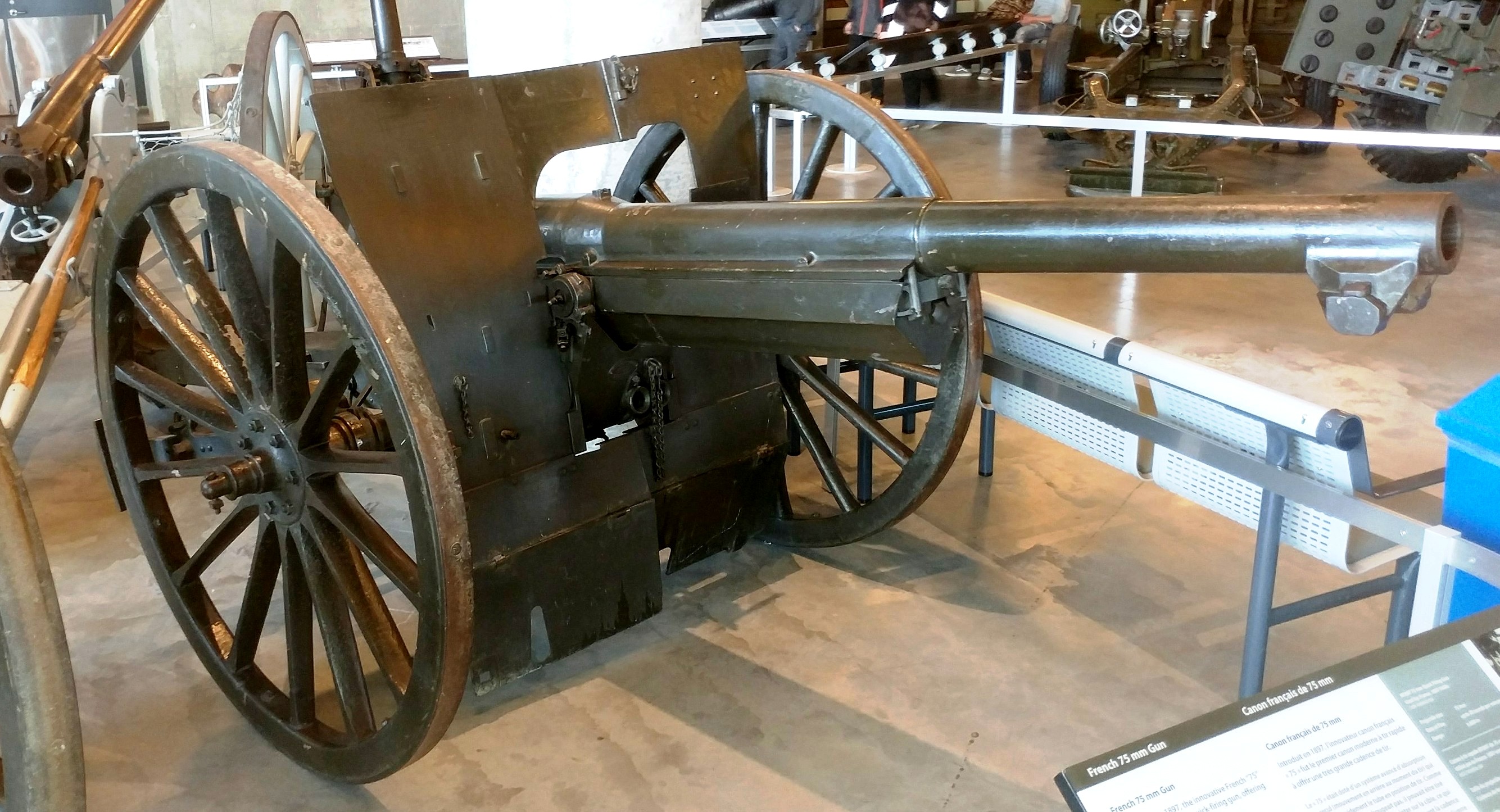

The history of the gun has been documented at length in many books and records. Many French cast muzzle-loading guns were employed in the era of New France and a number of them remain preserved and on display in Canada. A good number of French pieces of artillery were employed by Canadians on the Western Front during the Great War, and a handful of these are also preserved here.

French Translation of the technical data presented here would be appreciated. Corrections, amendments and suggested changes may be emailed to the author at hskaarup@rogers.com.

L’histoire de l’arme a été longuement documentée dans de nombreux livres et registres. De nombreux pistolets à chargement par la bouche en fonte française étaient utilisés à l’époque de la Nouvelle-France et certains d’entre eux sont toujours conservés et exposés au Canada. Un bon nombre de pièces d’artillerie françaises ont été utilisées par les Canadiens sur le front occidental pendant la Grande Guerre, et une poignée d’entre elles sont également conservées ici.

Une traduction au français pour l’information technique présente serait grandement apprécié. Vos corrections, changements et suggestions sont les bienvenus, et peuvent être envoyés au hskaarup@rogers.com.

Introduction:

This web page is primarily about where to find the historic guns of New France that are on display in Canada at present, specifically for the interested explorer, historian and military enthusiast. The French guns and their history in Canada are listed in a somewhat (but not necessarily) chronological order, and/or by bore calibre/inch size. A few of the artillery pieces found in Canada today may have been missed, and updates on where and what they are would be most welcome. One source described how in the process of taking apart his 150-year old home in Newfoundland, he discovered one corner of the house had been reinforced with an upright cannon cemented in the foundation. Many of the guns that were on display between the wars are known to have been cut up for scrap or placed in a landfill, which has led to a considerable reduction in the numbers of viewable historic guns. These guns have been part of Canada’s history, and as such every effort to preserve and document the survivors should be made in order to keep their story from fading.

The considerable number of cannon, guns and field artillery in use by the French and British forces that garrisonned the forts and fortresses, citadels and redoubts, blockhouses and field defence positions throughout Canada’s early history are numerous and varied and may not all be listed here. Much of Canada’s early military history is controversial. Crossbows and possibly hand-held cannons equpped the earliest European visitors who explored the coasts of Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, likely including those who came up the Saint John River in 1398 with Henry Sinclair’s expedition.[2] Although Sinclair’s explorations and those of other Europeans that came before him to Canada are in dispute, his documented use of cannon during his explorations from the Orkney Islands would place him in the earliest list of artillery users in Canada’s history.

The first officially recorded use of artillery in Canada took place in 1534 when Jacaques Cartier fired two of his ship’s cannon to repel the canoes of Mi’kmaq warriors on the North side of the Baie des Chaleurs (Chaleur Bay), off the coast of New Brunswick’s North Eastern shore.[3] A chronicler who accompanied Cartier recorded:

“We did not care to trust to their signs and warned the to go back, which they would not do, but paddled so hard that they soon surrounded our long-boat with their seven canoes. And seeing no matter how much we signed to them, they would not go back, we shot over their heads two small cannon…”[4]

This incident took place in the summer of 1534 at what is now Port Daniel on the north shore of the Bay of Chaleur. One year later, to satisfy the curiosity of Chief Donnaconna at Stadacona, Cartier had his ship’s Captain demonstrate an artillery broadside by firing 12 of his guns into the neaby woods, terrifying the native onlookers in 1535. On his third visit in 1541, Cartier brought guns ashore from three of his ships to protect the log fort at Charlesbourg Royal, about nine miles above Stadacona where the Cap Rouge River provided good anchorage.[5] It set a pattern followed by latter French colonists who set up defences at their settlements at Port Royal and Quebec by mounting small guns within their wooden stockades.

To determine the kind of guns that were being employed by Cartier and his ship’s crew one must have a look at the development of French Artillery from the Middle Ages forward to the age of New France. French artillery made its initial appearance in documents early in the 14th century. The initial weapons were rudimentary and included the pot-de-fer or the portable bâton à feu which fired stone or metal pellets.

With the outbreak of the Hundred Years’ War (1337-1453) gun development expanded exponentially. Small guns firing quarrels or lead pellets were mounted on ships and used to engage French enemies at the Battle of Sluys in 1340 and in the French defence of Tournai in August of 1340. Similar weapons were used by Edward III at the Battle of Crécy between 1345 and 1346. By the time of the collapse of the Treaty of Bretigny and the resumption of the war in 1369 guns had evolved considerably.

Up to 1370 guns were essentially small, in the weight range of 10 to 20 kg (20 to 40 lbs), and made of bronze or copper. After 1370 larger guns made of wrought or cast iron began to appear. Guns weighing more than one ton and firing 50 kg stone balls were used by the French to breech the walls of the fortress at Saint-Sauveur-le-Vicomte in 1375. Few such weapons existed in England before 1400. New firearms began to appear in the form of hand guns, small mortars and rebaudequins, complimenting but not replacing heavier artillery.

(Louis le Grand Photo)

Photos of a reconstruction of an arrow-firing cannon that appears in a 1326 manuscript.

(PHGCOM Photo)

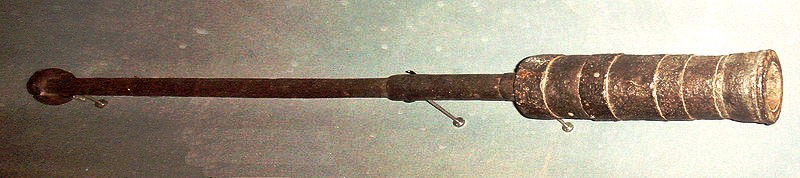

Bâton à feu, or hand bombard (1380). Musée de l’Armée.

The Bâton à feu, or Baston à feu (French for “Fire stick”), is a type of hand cannon developed in the 14th century in Western Europe. This weapon type corresponds to the portable artillery of the second half of 14th century. The Bâton à feu at the Musée de l’Armée in Paris has an hexagonal cross-section, and looks like a steel tube. It weighs 1.04 kg, and has a length of 18 cm. Its caliber is 2 cm. In order to facilitate handling, the metal piece was placed at the end of a wooden pole. The powder was ignited through a small hole at the top, with a red-hot steel stick.

(PHGCOM Photo)

Bâton à feu with its wooden pole, France, 1390-1400. Musée de l’Armée.

By the early part of the 15th century both the French and English armies had developed a wide variety of gunpowder weapons. The largest were known as bombards, weighing up to three tons and firing stone balls of up to 150 kg (300 lbs), although the French made greater use of them up to 1420. The bombards were often constructed by welding wrought iron bars together and binding them with circular reinforcing bracelets in a process known as “à tonoille”, much like the method for constructing wine barrels.

French Veuglaires, known as “fowlers” in England were developed with a length of up to 2 metres (6 feet) and weighing from 150 kg up to several tons. Crapaudins were shorter 1.5 metres to 4 metres (4 to 6 feet) and lighter than the veuglaires. Both the French and English used guns at the Siege of Orleans in 1429 and the army with Joan of Arc used guns effectively during the Loire campaign in the same year.

(Viollet-le-Duc image)

Swiss soldier firing a small hand-cannon, with his poweder bag and ramrod at his feet, late 14th century.

Portable hand guns began to be used on a wide scale. 14th century wood engraving. (Wikipedia)

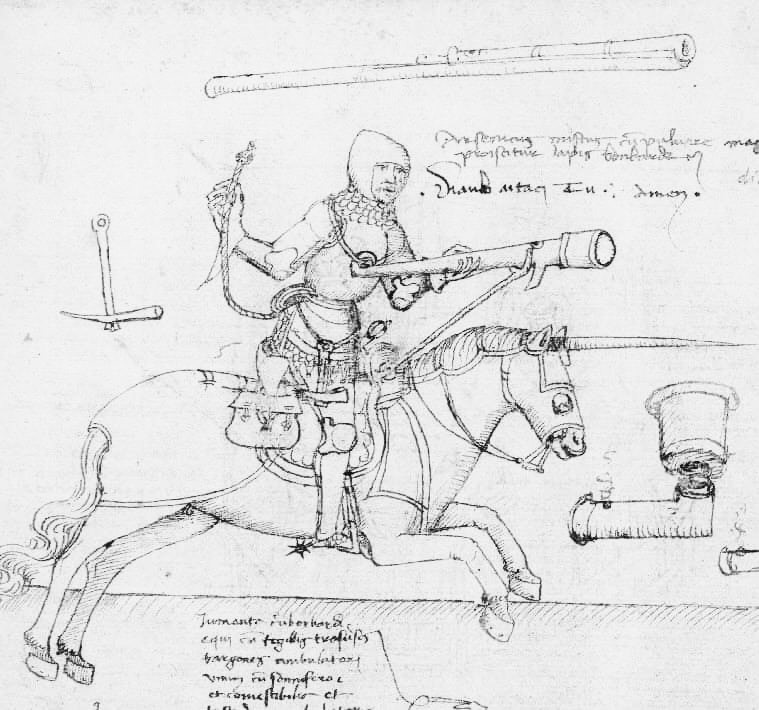

14th century drawing of a mounted culverinier armed with a hand cannon,.

(Wikipedia)

14th century wood engraving culveriniers using hand cannon, with one mounted on horseback. These soldiers are armed with light culverins. As the technology progressed, other small portable firearms were developed such as serpentines and couleuvrines. Hand held firearms did not replace the widespread use of longbows and crossbows during the Hundred Years’ War. Artillery, however, took on a major role in siege warfare, replacing the traditional wooden siege engines such as trebuchets, mangonels and catapults used since recorded warfare began.

From the 1430s, the artillery of France’s King Charles II was managed by Master Gunner Jean Bureau. It was used successfully at Meaux in 1439, Pontoise in 1441, Caen and during the Norman campaign (1449-1450). In the Battle of Castillon in 1453, grouped and entrenched French artillery decimated the English army. Artillery also began to affect military architecture leading to the development of walls that were lower and thicker in order to better withstand the battering of cannonballs.

Small cannons and hand culverin, 15th century. Musée de Cluny. (PHGCOM Photos)

The manufacture of firearms and cannon was an expensive business. In most cases, only kings or powerful overlords with considerable financial resources at hand could afford to have them made in numbers substantial enough to make a difference in a major siege or battle. Once they did have them, however, the effects could be devastating. In 1494, France’s King Charles VIII invaded Italy, bringing with him a siege train that included 40 bronze cannon with barrels eight feet long. These guns were easily elevated or depressed because they moved on two prongs or trunions placed just forward of the barrel’s balancing point. Except for the heaviest, these cannon were easily moved by lifting the trail of the gun mount and shifting it to one side or the other. They fired iron balls at ranges equal to those of earlier cannon that were three times their calibre. Charles guns were transported on carriages that increased their ease of mobility. His cannon struck the Italian fortresses with an effect that resembled German Blitzkrieg warfare of the Second World War. The Italian fortress of San Giovanni had once been besieged for seven years. The French gunners destroyed it in eight hours and then slaughtered the defending garrison. The era of the long siege was closing, but would never be completely eliminated.

(PHGCOM Photo)

Bombarde-Mortier, La Fère, wrought iron, second half of the 15th century. Length: 1 m, calibre: 35 cm, weight: 600 kg. In this weapon, the powder chamber was cast from molten metal, while the barrel was constructed “à tonoille”.

(PHGCOM Photo)

Wrought iron “Perrier à boîte” (Murder) breech-loading swivel gun, France, ca 1410. Length: 72 cm, calibre: 38 mm, weight: 41.190 kg.

(PHGCOM Photo)

Small wrought iron bombard, Metz, circa 1450. Length: 0.82 m, calibre: 175 mm, weight: 200 kg, ammunition: 6 kg stone.

(PHGCOM Photo)

Wrought iron bombard, circa 1450, La Chapelle-aux-Naux, near Langeais. Length: 2 m, calibre: 486 mm, weight: 1,500 kg, ammunition: 130 kg stone ball, range: 100-200 m.

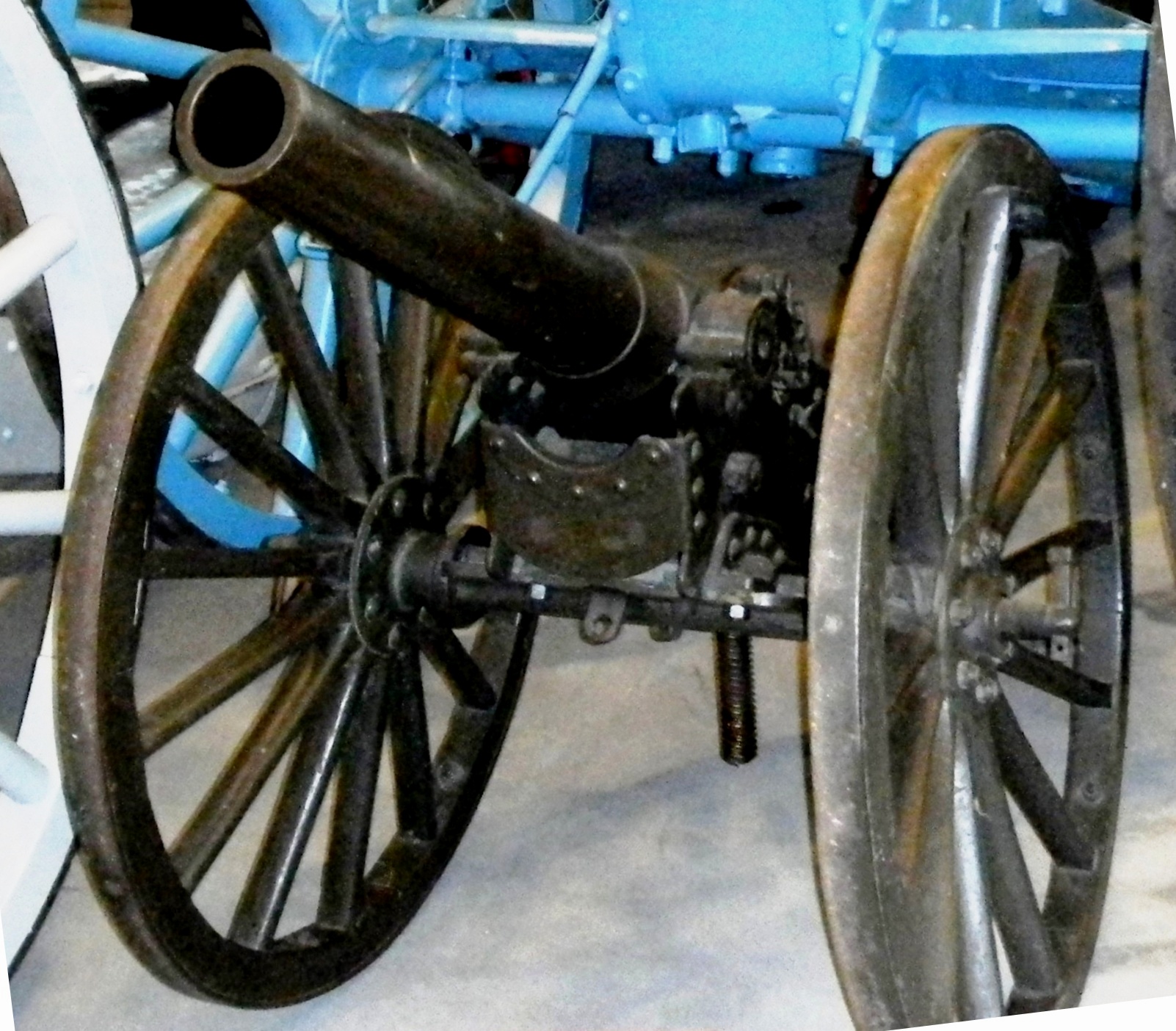

The Penetang Gun, 1630, Midland, Ontario. (Photos courtesy of Sainte-Marie among the Hurons Midland, Ontario. Ministry of Tourism and Culture)

The Penetang Gun is believed to have been brought to New France from the old world as can be seen by the insignia on the breech. It is stamped 1630, LeGC with a crown. The initials stand for”Le Grand Condé” who served under Prince Louis II as Captain General of the French Army in the mid-17th century. The gun’s breech is made of Bronze which has been cast in a hexagonal shape. Its iron barrel is reinforced with iron hoops.[6] The chase and breech-ends of the cannon are of separate construction. The wrought iron construction of the chase is associated with guns of the late 15th and early 16th centuries. The octagonal section of the cast Bronze breech and the shape of the cascabel also indicate a date in the first half of the 16th century. To be operational it would have been strapped with iron bands or strong ropes onto a wooden bed, which could itself be mounted on a yoke or carriage.

The gun would have been brought to Sainte-Marie by the Militia hired to protect the Jesuit Mission. The cannon was reputed to have been found in 1919 by Mr. King of Christian Island which links it with the Jesuit missionaries who fled Sainte-Marie in 1649. The missionaries and a large group of Huron people spent the winter of 1649-50 establishing Sainte-Marie II on Christian Island, in Georgian Bay. This gun was referred to by Father Jerome Lalemant in the August 1648 Jesuit Relation documents:

“On the 6th, the 50 or 60 Huron Canoes started from 3 rivers, which took on board 26 Frenchmen…5 fathers, one brother, 3 Boys, 9 workmen, and 8 soldiers, -besides 4 that were to be taken at Montréal; a heifer and a small piece of Cannon.”[7]

In the summer of 1609, Samuel Champlain made alliances with a group of natives in New France known as the Wendat (called Huron by the French) and with the Algonquin, the Montagnais and the Etchemin, who lived in the area of the St. Lawrence River. These tribes demanded that Champlain help them in their war against the Iroquois, who lived further south. Champlain set off with 9 French soldiers and 300 natives to explore the Rivière des Iroquois (now known as the Richelieu River), and during the expedition he became the first European to map Lake Champlain. Since they had not encountered the Iroquois up to this point, many of the men headed back, leaving Champlain with only two Frenchmen and 60 natives.

Somewhere in the area near Ticonderoga and Crown Point, New York, Champlain and his party encountered a group of Iroquois. A battle began the next day. On 29 July 1609 two hundred Iroquois advanced on Champlain’s position, and one of his guides pointed out the 3 Iroquois chiefs. Champlain fired his harquebus killing two of them with a single shot, and one of his men killed the third. The Iroquois turned and fled. This action set the-tone for French-Iroquois relations for rest of the century.[8]

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 4137596)

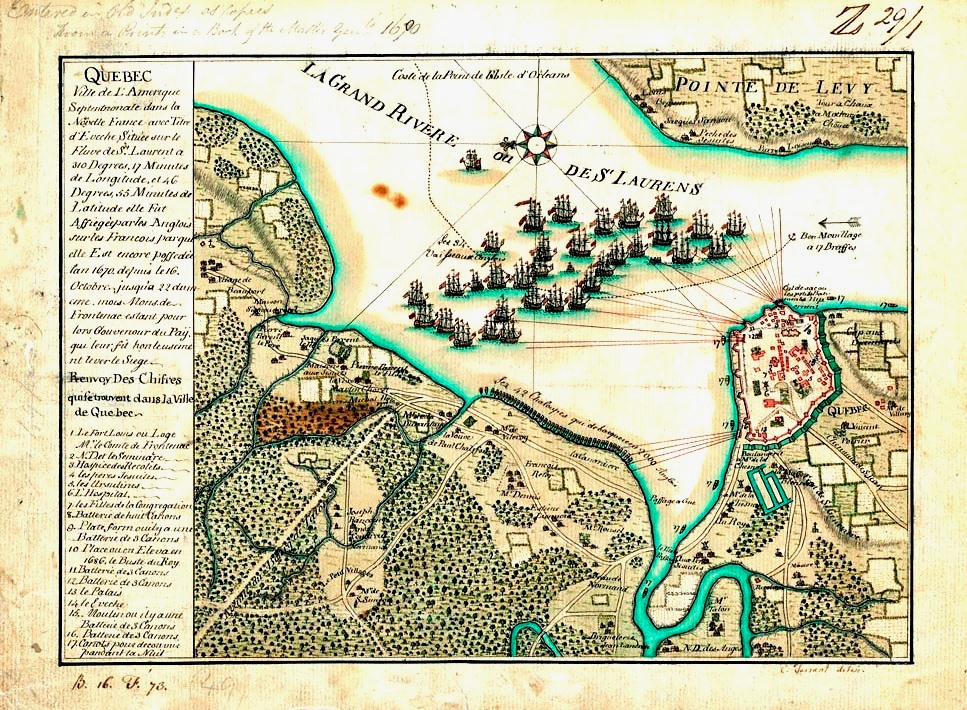

On 16 October 1690 several New England ships under the command of Sir William Phips, governor of Massachusetts, appeared near Québec City off the Island of Orleans, and an officer was sent ashore to demand the surrender of the fort. Governor Louis de Baude de Frontenac, responded with the famous words:

“Non, je n’ai point de réponse à faire à votre général que par la bouche de mes canons et de mes fusils.” – “I have no reply to make to your general other than from the mouths of my cannons and muskets.”

Part of Québec‘s defences were formidable for the time and when Frontenac had his gunners fire on the invaders’ ships, the upper town was protected by a good wall with intermittent batteries and more defensive works up near the Chateau Saint-Louis near Cape Diamond. In the lower town, there were two strong French shore batteries armed with heavy 18 and 24-pounder Naval cannons along the city’s harbour.[9] On the landward side, a line of earthworks punctuated with 11 redoubts enclosed the city from the western side. Frontenac had about 3,000 soldiers including three battalions of Colonial Regulars. As well, his gun batteries effectively covered the water approaches to Québec City, and as a result of their vigorous defence they successfully fought off Phips forces.[10]

Phips had brought 2,300 Massachusetts Militiamen and 32 ships although only four were of significant size. The British plan had been to land their main force on the Beauport shore, but a 1,200-strong English landing force under Major John Walley, Phips’ second-in-command, never got across the Saint Charles River. Frontenac had sent strong detachments of Canadian militiamen under Jacques Le Moyne de Sainte-Hélène, along with some Indians, into the wooded areas east of the river. When the English landed on 18 October, they were immediately harassed by Canadian militia, while the ships’ boats mistakenly landed the field guns on the wrong side of the Saint Charles. Meanwhile, Phips’s four large ships, quite contrary to the plan, anchored before Quebec and began bombarding the city until 19 October, at which point the English had shot away most of their ammunition. The French shore batteries had also proved to be much more than a match, and the ships were pounded until the rigging and hulls were badly damaged; the ensign of Phips’ flagship the Six Friends was cut down and fell into the river, and under a hail of musket shots, a daring group of Canadians paddled a canoe up to the ship to capture it. They triumphantly brought the ensign back to the Governor unscathed.

During the bombardment, the land force under Walley remained inactive, suffering from cold and complaining of shortage of rum. After a couple of miserable days, they decided to carry the shore positions and try to overcome the French earthworks. They set out on 20 October “in the best European tradition, with drums beating and colors unfurled,” but there was a skirmish at the edge of the woods. The New Englanders could not cope with the maintained heavy Canadian fire, and the Bronze field guns fired into the woods had no effect. Although Sainte-Hélène was mortally wounded, 150 of the attackers had been killed in action, and were utterly discouraged. They made a retreat in a state of near panic on 22 October, even abandoning five field guns on the shore. Frontenac learned from the lessons of the battle and as a result had a complete shore battery, known as the “Royal battery”, built immediately after the siege. It was shaped like a small bastion, and featured 14 gun embrasures to cover both sides of the Saint Laurence and the river itself.[11]

In 1696, the capital of Acadia was Fort Nashwaak (Fort St. Joseph), on the East side of the St. John River now part of the city of Fredericton, New Brunswick. Robineau de Vellebon was the Commandant in charge of a fort 200 feet square with four bastions and surrounded by a palisade and ditch. A New England force led by Colonel John Hawthorne prepared to attack the fort on 18 October, but in preparation for the assault, de Villebon had built a second palisade around the fort and mounted ten cannon and eight swivel guns on its walls. The British set up camp and a battery across the Nashwaak River but after two days of ineffective bombardment and suffering the harassment of French and native skirmishers in the woods, the British withdrew on 20 Oct.[12]

Medieval gunners appear to have been organized in groups. 320 Burgundian gunners reportedly took part in the Battle of Ravenspur in 1471, John of Burgundy allegedly had 4000 handgonnes in his armoury, and at the battle of Stoke, the earl of Lincoln is said to have fielded 2000 handgonnes. Scandinavia Karl Knutsson reportedly had enough gunners on his campaign against Skåne to organize them into one separate unit, marching under the flag of Saint Erik, the national saint of Sweden. Karl Knutsson is also reported to have brought “Wagon guns” (kärrebössor) on the same campaign.

Guns were given names on the recommendation of Christine de Pisan who wrote on methods of waging war in the early 15th century. She noted that a commander had to field a variety of different calibre guns and it would be difficult to trust the common soldier to remember which gun should be supplied with which ammunition. To resolve this she believed the guns should be referred to by name, stating for example, “I would like Katrina placed over here, and Anna placed over there!” The soldier would then know what gun was which, and what kind of ammunition would go with it.

French Naval Guns and the French Artillery in Canada

The Ministère de la Marine was responsible for everything related to colonies: men, provisions, equipment and armament. It also administered the French Navy. Therefore, it is not surprising that this ministry supplied its oversea holdings with naval ordnance. The Canadian forts and port defen were equipped with iron naval guns, not army ordnance.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 2895486)

English landing on Cape Breton Island to attack the fortress of Louisbourg in 1745.

Louisbourg and Acadia were separate French colonies, distinct from Canada, with its own colonial government. Louisbourg had been captured by American colonists in 1745 and then returned to France by treaty in 1748. Both colonies shared many of the same problems and concerns, but deviated in others.

By the end of the War of Austrian Succession (1740-1748), the French Navy was in very poor condition. In the Fall of 1747, France lost a series of engagements trying to re-supply its colonies. The French were forced to rebuild their fleet retiring all the pre-1740 ships. Entering the Seven Years’ War, the French had some 55 ships in their combined battle-fleet (Winfield and Roberts 2017). These new ships would have been armed with iron guns. Throughout the Seven Years’ War, the French lacked both sailors and ordnance for their ships. Completed ships would sit idle in ports. In some instances, ships would be sent to sea under-gunned, i.e., armed with 18-pounders instead of 24-pounders. Under these circumstances, new large smoothbore guns could not be sent to Canada. However, the lack of sailors was even more pressing. By paying significantly higher wages than the French Navy, privateers siphoned off many of the most experienced sailors. Attempts to control the privateers failed. The privateers were simply “injecting” too much money into the port cities to shut them down (Dull, 2005).

In the 18th Century, the French Navy was totally independent from the French Army, its equipment (artillery pieces, muskets…) were manufactured in different facilities. There was a bronze foundry in Toulon, iron foundries for large pieces in Berry and Bourbonnais, and in Ruelles, Saint Robert, Plancheminier, etc. There was also an arm factory in Tulle.

The French had adopted a straightforward approach to naval ordnance. From 1689-1766, the length of the guns was locked at specific values. New gun patterns were designed and gun weights varied, although the lengths were fixed (Winfield and Roberts 2017). This allowed an orderly and predictable approach to ship layout while protecting the hulls from concussive damage generated by guns that were too short.

Establishments 1689-1690, 1721, 1733, 1758

Calibre Length

36-pounders 10 ft. 5.39 in. (3.20 m)

36-pounders 9 ft. 11.69 in. (3.04 m)

24-pounders 9 ft. 11.69 in. (3.04 m)

18-pounders 9 ft. 5.39 in. (2.88 m)

12-pounders 8 ft. 11.09 in. (2.72 m)

8-pounders 8 ft. 4.79 in. (2.56 m)

6-pounders 7 ft. 4.19 in. (2.24 m)

4-pounders 6 ft. 3.59 in. (1.92 m)

Note: In the 18th Century, the French and English definitions of inch and pound did not agree. 1 French inch = 1.066 British inches. As such, the French 16-pounder is equivalent to the British 18-pounder.

Casting iron is a more difficult process than casting bronze. With larger pieces, the iron would start to cool before the full casting could be poured. This resulted in repeated failures. The needed techniques and protocols took time to develop. French iron 24-pounders and 36-pounders were first reliably cast in 1688 and 1691, respectively. In 1671, the French naval stores held some 1,906 bronze and 3,184 iron cannon. In 1696, there were only 26 bronze cannon left in the French stores that were 12-pounders or less. By 1712, the bronze cannon had decrease to 884 guns and the iron increased to 7,328 guns (Peter 1995, Page 23). The remaining bronze guns were large-bore. Unlike iron, unwanted bronze guns could be melted down and re-cast as new cannon, a common practice.

Bronze guns were lighter, but the material cost of the ores was many times higher than that of iron. Sea-handling was made easier with the lighter weight bronze, especially with reference to the upper deck guns. Besides being cheaper to produce, iron guns could accept a heavier gunpowder charge resulting in greater range and striking power. Iron guns could be fired at higher sustained rates than bronze guns, but this was more of a concern in siege warfare than at sea. However, sudden and catastrophic bursting was much more likely with an iron gun. Overheating of a bronze gun was a concern, drooping barrels, but any failures were generally not catastrophic. In this regard, bronze guns were safer for their crews than iron guns.

Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, the French Army employed the 16-pounder, not the 18-pounder (Persy 1832). The other bore diameters are shared between the Army and Navy, but not in this case. In August 1757, at the Siege of Fort William Henry, Montcalm’s siege train included five 18-pounders. These were undoubtedly naval guns that were fitted to “de campagne à grand rouage” — travelling carriages (siege carriages).

The French Navy needed mortars on bomb ketches and gun boats. The 12-inch mortar was the most common, but 8-inch mortars were placed on some ships. These mortar patterns may have been shared between the French Army and Navy – the bore diameters are standard for both services. However, there was also a mortar of a very peculiar model in use in the Navy. This model had a the mortar and its carriage cast in a single piece with an elevation of 42-45°. In number on a bomb ketch, they could be formidable against a city besieged from the sea.

Artillery Pieces in use in North America

At the start of the war in North America, the ordnance available for the defence of Canada was composed of iron naval guns plus a very few small-bore bronze guns (O’Callaghan, Documents X, Page 195). The bronze ordnance of the army’s Valliére System (1732) was not being sent to Canada. The largest bronze cannon were the three 4-pounders at Québec. There were no howitzers anywhere in Canada. Later during the conflict, any bronze ordnance in Montcalm’s siege train was captured British artillery (30 bronze pieces plus a dozen coehorns). The guns in Canada should be thought as being “older” iron naval guns, iron guns from damaged ships reaching Canada, or captured British ordnance.

The Canonniers-Bombardiers de la Marine used various types of artillery pieces in service in the Marine Royale and in the French coastal fortifications. The great majority of the artillery pieces used in the colonies were made of iron and painted black since they were initially destined to serve on board warships. They were mounted on wooden carriages painted red.

In 1749, Québec had a formidable ordnance store, some 178 cannon including twenty-five iron 24-pounders, twenty-two iron 18-pounders and thirty-six iron 12-pounders. There were no army 16-pounders. Before the start of the war, the most common mortar in Canada was the 6-inch iron mortar (5 pieces).

In the colonies, the heaviest pieces were usually sent to the eastern forts which were the most exposed to British attacks. On the other hand, certain western forts (Fort Détroit for instance) were equipped only with swivel guns considered obsolete by colonial authorities. Nevertheless they were sufficiently resilient to last till the end of the French Regime.

In 1749, Fort Saint-Frédéric, the cause of much of New England’s resentment against Canada, served as a staging point for raids heading south. Deep in the wilderness, Fort Saint-Frédéric was decidedly unique — the main feature was a four-story-tall masonry artillery tower (octagon). Against assault with cannon and mortar, it was not a strong position being dominated by the adjacent hillsides. At that time the fort had the following artillery pieces:

- 2 x iron 6-pounder guns

- 17 x iron 4-pounder guns

- 1 x iron 2-pounder gun

- 2 x bronze 2-pounder guns

- 1 x iron grenade mortar

- 18 x swivels

- 25 x boîtes de pierriers (breech-loading swivels)

Similarly, by 1749, Fort Niagara was armed with:

- 4 x iron 2-pounder guns

- 4 x iron 1 ½-pounder guns

- 1 x iron 6-in mortar

- 1 x iron grenade mortar

- 5 x swivels

- 13 x iron boîtes de pierriers (breech-loading swivels)

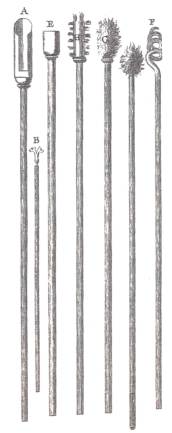

French artillery tools

A: ladle

B: lint stock

E: rammer

H, G, I: sponges

Source: L’Encyclopédie from the collection of Jean-Charles Soulié

In July 1759, Niagara surrendered to the British. During the war, the French captured only a single British iron 12-pounder. At Niagara, some twenty-two iron 12-pounders were surrendered. In 1749, there were only thirty-six 12-pounders in all of Canada. Québec (178 guns) had the artillery stores to supply Fort Niagara, but it is extremely doubtful that more than half of the 12-pounders would be stripped from Québec to supply Niagara. These Niagara 12-pounders were naval guns that had been in Canada for only a few years, but they are likely “old guns”. Notably, the French at Niagara have no trouble with supplying the needed gun carriages.

Almost all of the artillery pieces discussed here came from France. However, there existed a foundry, the “Forges du Saint-Maurice” (the sole foundry in Nouvelle France), near Trois-Rivières. The primary focus of the foundry was the production of bar iron to be shipped to France. Typical production was near 350,000 pounds per year, but the output was quite variable from year to year. Peak production was reached in 1745 when 480,000 pounds of iron were produced. In 1747, a few 4-pounders were cast and then sent to France, but these guns all failed the proof-testing (Samson 1998, Page 226). In 1748, six 4-pounders, six 2-pounders, five 6-inch iron mortars, and six iron grenade mortars were cast. That year, Saint-Maurice also produced 161 six-inch shells (5″ 8 line), 110 nine-inch shells, 144 twelve-inch shells, and 2,700 cannon shot. Unlike cannon, mortars could be strengthened simply by bulking up the wall thickness, but without lengthening the bore. This made them ideal for colonial munition casting. Apparently, one of these 6-inch mortars was part of Montcalm’s siege train at both Oswego and Fort William Henry. Shell availability would have been the determining factor on how many of these mortars would be incorporated into the siege train, not the number of mortars available. Outside of grenade mortars, this may have been the only Canadian made ordnance in Montcalm’s siege train. The other shell sizes fit the two large-bore mortars already at Québec. After 1752, difficulty in staffing the foundry with skilled workman was a distinct problem and limited the output.

The limited ability for Canada to manufacture ordnance, gunpowder, or shot is highlighted below. From a Memoir of Chevalier Le Mercier on the Artillery in Canada (O’Callaghan, Vol. X, Page 655; undated but appears to be Summer or Fall 1757):

Article First – Concerning Québec, the town at present sufficiently provided with cannon, but it is highly necessary that it should have a proportionate quantity of shot. Seventeen iron mortars arrived this year, 4 of which were 12-inch, 5 of 8, and 8 of 6-inch, and only a few shell came, the most of which have not the necessary vent. A requisition was made last year for four Cominge bronze mortars (18-inch) and for four mortars of 12-inch 4 li. diameter, with conic chamber capable of containing 11 @. 12lbs. of powder; they have not been sent; ’tis certain, however, that had we mortars of this description, no ships could anchor in the basin of Quebec. The mortars which we received were intended for sieges and forts; this was the reason they were required to be bronze, as they are easier of transportation; they are of iron, and 5 and 8 inches; some of them have their trunnions broken in France, the thickness of the metal is lessened by nearly an inch at this point. They had to be fastened to their carriages with iron bands, which renders the transport of them difficult; it is, morever, impossible to elevate them, as they are immovable.2d.Although there are none in Canada who can manufacture shell or shot, some might, however, have been made at the forges of Saint-Maurice; but that establishment can scarcely supply metal necessary for the castings needed for service in the Colony. Therefore ’tis useless to think of it; should the King order it, however, ‘twould be necessary to send from France some moulders in clay and sand for the shells.

From M. de Vaudreuil to M. de Massaic, Minister of the Marine and Colonies (O’Callaghan, Vol. X, Page 863, partial transcription):

My Lord, Montreal, 1 November, 1758, I have the honor to transmit to you the requisition furnished me by Chevalier Lemercier, of the ammunition to be sent this year from France. I have examined it, my Lord, with attention; have called for a report of what we have in the Colony, and have seen it impossible to make any retrenchment. I shall require that supply indispensably, to enable me to defend the Colony the King has confided to me, if attacked, as there is every appearance it will be. What is wanting can be made up by multiplying the fire of artillery and musketry, and taking up good positions; but ’tis impossible to avoid consumption of powder in war; this is the truth I beg you to place in the proper light before his Majesty. You like likewise be able, my Lord, to observe to the King that there is no country where so much of it is consumed, both for hunting and distribution among the Indians; burning of powder is equally a passion among Canadians, but I think we gain thereby in the day of battle, by the correctness of their aim in firing. Were it not for the ammunition furnished me successively by the Belle Rivière (Monongahela), Chouagouin (Oswego), and Fort George (Fort William Henry), I should not have had enough either for attack or defence. The Company of the Indies (Lower Mississippi Valley), which used to import annually and consume forty thousand weight, had no more powder. The consumption may, even in time of peace, be estimated at sixty-thousand weight.

References

Chartrand, René 2003. Napoleon’s Guns 1792 – 1815 (2): Heavy and Siege Artillery. Osprey Press. Oxford.

Dull, Jonathan. 2005. The French Navy and the Seven Years’ War. University of Nebraska Press. Lincoln & London.

O’Callaghan, E. B. 1858. Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York: Procured in Holland, England and France. Vol. X, Weed Parsons and Company, Printers, Albany, pp. 195-196

Persy, N. 1832. Elementary Treatise on the Forms of Cannon & Various Systems of Artillery. Translated for the use of the Cadets of the U.S. Military Academy from the French of Professor N. Persy of Metz. Museum Restoration Service, 1979.

Peter Jean 1995. L’artillerie et les Fonderies de la Marine, Sous Louis XIV. Economica, Paris.

Samson, Roch. 1998. The Forges Du Saint-Maurice: Beginnings of the Iron Steel Industry in Canada, 1730-1883. Department of Canadian Heritage, Parks Canada.

Winfied Rif and Stephen S. Roberts. 2017. French Warships in the Age of Sail 1626-1786: Design, Construction, Careers, and Fates. Seaforth Publishing, Barnsley, South Yorkshire.

Acknowledgement

Kenneth P Dunne and Jean-Louis Vial for the initial version of this article

Source: http://www.kronoskaf.com/syw/index.php?title=French_Naval_Guns_and_the_French_Artillery_in_Canada

French Field Artillery in North America

At the start of the war in North America, the ordnance available for the defence of Canada was largely composed of iron naval guns. This is understandable as Canada was administered through the Minister of Marine and Colonies; this office also administered the French Navy.

The French Navy was armed with 4-, 6-, 8-, 12-, 18-, 24-, and 36-pounders. By the 1720s, these were nearly always iron guns. The individual guns being supplied to Canada are thought to be older guns, no longer wanted in sea service or taken from heavily damaged ships that had reached Canada. The French Navy also employed a number of mortars: 8-, 9-, and 12-inches, for use in bomb ketches and gunboats (Douglas 1855, p. 178; British Nomenclature 8 ½-, 10 ½- and 12 ½-inches). All these mortars match French Army designations, pre-Vallière.

For the artillery present in Canada (1749), there is detailed list by location (O’Callaghan 1858, referenced here as Documents Vol. X, p. 195). This list includes all ordnance from the largest cannon to swivel guns and iron grenade mortars for a dozen posts. Only Québec had a formidable ordnance store, some 178 cannon including twenty-five iron 24-pounders, twenty-two iron 18-pounders and thirty-six iron 12-pounders. However, there were only a few mortars at Québec: a single bronze 12-inch 4-line mortar, a single bronze 9-inch 6-line mortar, a single iron 6-inch mortar, and three iron grenade mortars. Montréal housed twenty-seven iron 6-pounders, five iron 4-pounders, a single iron 3-pounder, two 6-in iron mortars, and two iron grenade mortars. The largest bronze cannon were three 4-pounders at Québec. There were no howitzers anywhere in Canada.

The Saint-Maurice Foundry at Trois-Rivières in Canada produced bar iron for export to France, but munitions were manufactured. In 1748, five 6-inch iron mortars and six iron grenade mortars were cast. That year, Saint-Maurice also produced 161 six-inch shells (5″ 8 line), 110 nine-inch shells, 144 twelve-inch shells, and 2,700 cannon shot. One of these 6-inch mortars was in Montcalm’s siege train at Oswego and at Fort William Henry. After 1752, difficulty in staffing the foundry with skilled workman was a distinct problem and limited the output. These Canadian-made 6-inch 3-line mortars were slightly smaller in the bore and shell than French-made 6-inch mortars.

Artillery in Canada

Neither the French or British Navies were fitted with bronze guns, it was simply too expensive to equip fleets in bronze. However, both the French and British Armies favored the use of bronze guns. Even in Europe, the number of guns in a field army was at most only a few hundred while thousands of guns would be needed to equip a fleet. In North America, artillery trains would only approach a few dozen guns.

In 1732, the French Army adopted the Vallière System of Ordnance, but very few pieces, if any, seemed to have reached Canada. Under the 1732 Vallière System, there were 4-, 8-, 12-, 16- and 24-pounders; 8- and 12-in mortars, but no howitzers until about 1749 (Persy 1832) or slightly earlier. The guns were all bronze and there was no distinction between siege and field pieces. These guns were long, accurate and were intended to hit hard at range, but they were decidedly heavy. The sole exception was the short 4-pounder à la Suédoise which was a later addition (Model 1740) – this gun is often considered to be outside the Vallière System.

Bronze is approximately 90% copper and 10% tin. True bronze is 90% copper and 10% zinc. Ordnance was only manufactured in bronze or iron. The value of bronze ordnance is as mobile field guns or as part of a siege train with the leading attribute being their lighter weight when compared to iron. Though bronze is denser than iron, bronze is more elastic than iron. Bronze guns could be cast with thinner walls than iron guns of the same caliber and length, thereby achieving lower barrel weights. Language confusion occurs around bronze guns, the British routinely reference bronze guns, even though they were bronze. At the same time, the French would reference “canon de fonte” which literally translates to cannon cast, but the meaning is a bronze gun or mortar; iron guns would routinely be referenced as iron or “fer.”

The bronze army cannon and gun carriages of the Vallière System were simply not being sent to Canada. Under Vallière, mortars are manufactured only as 8-in and 12-in bronze pieces. During the war, any army ordnance arriving from France were older iron pieces, pre-dating the Vallière System. In 1757, seventeen mortars arrived from France. Eight were iron 6-inch mortars, these pieces were at least 25-years old and not in good condition (Documents X, p. 655). The 6-in designation links to the French Army. The other mortars were larger, but they are iron suggesting older ordnance. Outside of supplying mortars, it is difficult to identify French Army contributions to the Canadian artillery store.

Montcalm’s Bronze Artillery Train

By necessity, the French adapted and after a series of victories assembled a bronze siege train from captured British guns. By the end of 1757 and described in British nomenclature, the French had captured at least eight large-bore bronze pieces:

- 1 x 18-pounder

- 2 x heavy 12-pounders

- 4 x 8-in howitzers

- 1 x 10-in mortar

These pieces had the attribute of “range”. Plus there were another 21 “smaller” captured bronze pieces:

- 4 x medium 12-pounders

- 6 x light 12-pounders

- 6 x 6-pounders

- 5 x royal 5 ½-in mortars

Between 1755 and 1757, the French had captured some thirty bronze pieces of some size. In addition, there were about eleven 4 ⅖-in coehorn bronze mortars, most from Oswego – a few may have been coehorn howitzers. Another sixty iron guns would be captured including one iron 12-pounder, six iron 9-pounders, two iron 8-in mortars, and two iron 8-in howitzers; the remainder being small-bore iron ordnance (6-inches or less) and coehorns. Besides the ordnance, critical gunpowder and shot stores would be captured. By the end of the war, the shortage of gunpowder and shell was more severe than the shortage of artillery pieces (Documents Vol. X, pp. 655, 863).

The six captured light bronze 12-pounders were little more than heavy-hitting 6-pounders; these guns should not be over-valued. At this time, the pattern for the light British 12-pounders was just 1,000 pounds, five-foot-long. Powder charges were reduced compared to medium 12-pounders. During the Napoleonic Era, the same five-foot-long light 12-poundr weighed about 1,340 pounds.

For three years, thee captured British ordnance and stores were key to Montcalm’s success. After 1758, there would be no more victories over the British. At least through 1758, Montcalm kept his bronze ordnance close-by and did not assign these guns to any fortifications, such as Niagara or Carillon. The only notable exception is the presence of a 9-in bronze mortar at Carillon on 24 September 1757. The only other bronze 9-in mortar was at Québec.

However, the capture of so much British ordnance at the beginning of the war should not be allowed to solely dominate the picture. French forts were still predominantly equipped with iron naval guns. During the war, a significant number of additional naval guns reached Canada.

From the viewpoint of Montcalm, the value of the captured bronze ordnance was largely with the shell pieces (mortars and howitzers) and the captured ammunition and gunpowder stores. In all likelihood, an appreciable supply of 9-inch shell was captured at Fort William Henry — the British had moved their 9-in mortars (10-in – British nomenclature) south to Fort Edward, but not all the shell storage. Montcalm’s 9-in mortar was probably one of the few long-range shell pieces with an ample ammunition supply. The only large-bore howitzers available to Montcalm were the captured 8-in howitzers (six pieces, both bronze and iron). Supplying shells for the 8-in howitzers and 8-in mortars would prove much more difficult, these were designed to accept a 7.75-inch diameter shell, not a good fit for the shell stores then in Canada. Having lighter weight bronze cannon was more of a bonus than anything else. The movement and use of iron cannon does not represent any real problems for Montcalm, even as it regards the naval 18-pounders. These French naval cannon were excellent guns – hard hitting with range, but too heavy for use in maneuvering armies or engagements. French transport was chiefly done via water and the short difficult portages were “human”. Any movement by wheeled carriages required horse or oxen and the fodder to feed the animals. Outside the Saint-Laurent River Valley, there was little fodder for the animals. As attested by Bougainville, the French would not be able to move south via a “wheeled” artillery train simply because of the lack of fodder.

British vs French Nomenclatures

In the 18th century, the identity of measurements is not set. The confusion is made severe as the language is often the same, but with different values: 1 French inch = 1.066 British inches; 1 French foot = 1.066 British feet; and 1 French Parisian pound (weight) = 1.073 British pounds (9126 grains per a French pound; 8,455 grains per a British pound). Because of these inconsistencies, each nation would describe the same gun differently. It is very easy to confuse British and French references to the same piece of ordnance. The following list represents British ordnance captured and how those pieces would likely be referenced in French correspondence.

Ordnance Nomenclatures

Captured British French Reference

18-pounder 16-pounder

12-pounder 12-pounder

Light 12-pounder 12- or 11-pounder

9-pounder 8-pounder

6-pounder 5- or 6-pounder

10-inch mortar 9-inch mortar

8-inch mortar or howitzer 6- or 7-inch mortar or howitzer

Unlike the French Army, the British Army manufactured heavy, medium and light pieces of the same calibre. If a captured British piece was a heavy gun, the French might assign it a slightly different designation, a higher number. At Oswego, two of six bronze 12-pounders that were captured were labeled as 14-pounders. The other four bronze 12-pounders were designated 12-pounders; the captured bronze 18-pounder was designated a 19-pounder. This protocol was adopted to aid the French ordnance clerks in their inventory management, nothing more. The protocol remained intact for four years (North American duty). Outside the 3-pounder, if the French described a gun with an odd number, it was likely a captured British gun. The same is not true for mortars, particularly as it regards any 9-inch mortar. There is an older French Army 9-inch 6-line bronze mortar pattern – before the start of the war, one of these mortars was at Québec. The most common mortar in Canada before the war was the 6-inch iron mortar – five pieces (Canadian-made); eight more would be sent during the war (French-made). Iron grenade mortars were also common, but only a few at any location (Documents X, p. 195). All howitzers used by Montcalm were captured British pieces, either bronze or iron.

Principal Artillery Officers

Francois-Marc-Antoine Le Mercier was Montcalm’s principal artillery officer. Le Mercier was Canadian and headed a 50-man company of Canonniers-Bombardiers de la Marine these were naval troops, long established in Canada. Mercier had an awkward relationship with the French regular officers under Montcalm as he was closely tied to Francois Bigot (the corrupt Colonial Intendant) and Lotbinière (the Canadian Engineer) who designed and profited so much during the construction of Fort Carillon (Bougainville Journals).

In 1757, under Le Mercier and Lotbinière, the French managed to construct both “siege” carriages and garrison carriages for Montcalm’s artillery train being assembled at Carillon. Following the victory at Fort William Henry and Montcalm’s withdrawal to Canada with the vast majority of his artillery train, there were still some 28 garrison carriages and 30 travelling gun carriages at Carillon, including two travelling carriages for 18-pounders, “de campagne à grand rang” (Le Mercier, September 24, 1757 – Library of Canada Archives, MG1-C11A). Among the skills of the Canonniers-Bombardiers seemed to be the art of constructing travelling gun carriages, essentially siege carriages. Undoubtedly, both Lotbinière and Mercier financially gained from each carriage produced and sold to the King.

References

Bougainville, Louis Antoine. 1964. Adventure in the Wilderness. The American Journals of Louis Antoine de Bougainville, 1756-1760. Translated and Edited by Edward P. Hamilton. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

Douglas, Howard. 1855. A Treatise on Naval Artillery. John Murray, London.

Dunnigan, Brian Leigh. 1996. Siege – 1759: The Campaign Against Niagara. Old Fort Niagara Association, Youngstown, New York.

Hughes, B.P. 1969. British Smooth-Bore Artillery. Stackpole Books, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

Le Mercier, Francois-Marc-Antoine. September 24, 1757. Etat de l’artillerie, ustensiles et munitions de guerre qui sont effectives au Fort de Carillon. Date of October 30, 157 is also attached. There are some 30 “siege” carriages and 28 marine/garrison gun carriages plus a half-dozen mortars beds in the inventory. As travel is by water, limbers are few. Library and Archives of Canada. MG1-C11A, Volume 102, Microfilm Reel Number C-2421. Item ID Number: 3073056. On-line.

O’Callaghan, E. B. 1858. Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York: Procured in Holland, England and France. Vol. X, Weed Parsons and Company, Printers, Albany. Online.

Pargellis, Stanley 1936. Military Affairs in North America, 1748-1765. “MANA”. Selected Documents from the Cumberland Papers in Windsor Castle. American Historical Association, 1936. Reprinted: Archon Books, 1969. Online.

Persy, N. 1832. Elementary Treatise on the Forms of Cannon & Various Systems of Artillery. Translated for the use of the Cadets Of the U.S. Military Academy from the French of ProfessorN. Persy of Metz. Museum Restoration Service, 1979.

Acknowledgements

Kenneth P Dunne for the initial version of this article

Source: http://www.kronoskaf.com/syw/index.php?title=French_Field_Artillery_in_North_America

Casting of cannon in New France

Cast Irons from Les Forges du Saint Maurice, Quebec. A Metallurgical Study. Henry Unglik. Studies in Archaeology Architecture and History National Historic Parks and Sites, Parks Service, Environment Canada©Minister of Supply and Services Canada 1990.

Historical Background (Parks Canada)

Information concerning Les Forges du Saint-Maurice comes from two mainsources: historical records (Swank n.d.; Harrington 1874; Berube 1983,1984 [pers. com.]; Miller 1968; Trottier 1980; Beaudet 1983) and archaeological research carried out at the site by the Canadian Parks Service (Cox1977; McGain 1977; Nadon 1977).

Les Forges du Saint-Maurice was founded on the Saint-Maurice Rivernear Trois-Rivieres, halfway between Montreal and Quebec City on the St. Lawrence River. Iron ore was discovered in the vicinity of Trois-Rivieres as early as 1667 and the mining of the ores started in 1672. The ironworks were formally established in 1730 when Louis XV granted a royal commission to a resident of New France, Francois Poulin de Francheville, who was a Montreal merchant and the owner of the Saint-Maurice seigneury. The first, short-lived, effort of iron smelting directly from ore was carried out in a Catalan-type forge constructed in 1733. Using the direct-process technology copied from New England, the Francheville bloomery forge produced during its entire operation (in 1734) one ton of wrought-iron bars. The small output hardly exceeded nine kilograms of iron per day.

In 1735 a new company, Cugnet et Cie., was formed to build a profitable enterprise using the indirect reduction process. The ironmaster, Olivier deVezin, soon arrived from France to take charge of Les Forges. The construction of a blast furnace with a capacity for daily output of 2.5 tons of pig ironbegan in 1736. In the same year the master’s house, the lower forge, and the lodgings for the workers were started (Fig. 1). The smelting of bog-iron orein the charcoal-fired blast furnace was carried out regularly by 1738. Two finery hearths were erected in 1736 in the lower forge and two in 1739 in a second forge (the upper forge). In 1740 the blast furnace was 4.5 metres high. A water wheel operated wooden bellows, and a cold blast was supplied by a tuyere. All the necessary raw materials for the manufacture of iron —i.e., pure bog ore, plentiful charcoal, and good-quality limestone — were found nearby. Charcoal from deciduous trees was used for the furnace and from coniferous for the forges. Iron was produced in the form of castings obtained directly by pouring molten iron from the blast furnace into prepared moulds. These castings were pots, kettles and other hollow ware, stoves, and such military equipment as cannons, mortars, and cannon balls. Wrought-iron bars of various kinds were manufactured at the hammer forge. A regular labour force of about 30 men plus about 240 seasonal workers was employed at Les Forges in 1742. Cugnet et Cie. went bankrupt in 1741 and the ownership of Les Forges reverted to the Crown in 1743.

In 1760 Canada passed into the possession of the British and with it Les Forges du Saint-Maurice. Production ceased completely in 1765 after five years of scaled-down operations; it was successfully resumed between 1767and 1793. In 1793 Matthew Bell became one of the leaseholders of Les Forges, which thrived for most of the 53 years of his leadership. In 1815 the total labour force reached about 300 men, including about 50 skilled workers living in the St. Maurice community, and the rate of production increased substantially. Heating stoves, large potash kettles, “machines for mills,” and ploughshares were turned out in large numbers. In the 1820s a cupola furnace or an air furnace was installed in the area of the blast furnace. By that time only some pig iron went for export.

In 1846 the British government sold the ironworks to Henry Stuart. A period of technological changes followed, mainly modernization of the blast furnace. Its dimensions were increased and it was equipped with water-cooled tuyeres, a hot-blast stove, and an air compressor powered bya turbine. The daily production of the blast furnace was doubled to more than four tons, of which ten per cent was white and ten per cent mottled iron. Three tons of ore and one ton of charcoal were required to make one ton of iron.

Les Forges began to decline roughly a decade before John McDougall bought the ironworks in 1863. Iron castings production was abandoned. Very little wrought iron was refined in a Walloon hearth, and most of it was employed by the blacksmith for local use. After production of wrought iron ceased in the late 1860s, cast iron remained the only product of Les Forges. This high-quality metal was sent to large foundries in Montreal for making railway car wheels. The blast furnace was about 9 metres high in 1873, and the internal diameter at the hearth was 0.75 metre, at the bosh 2 metres, and at the throat 1 metre. It had two tuyeres and a cold blast. Due to an economic depression the plant was shut down in 1877, although it reopened in 1880. Construction of a new, modern blast furnace a year later, in 1881, did not revive the industry.

The original blast furnace was finally abandoned in 1883, and the ironworks was closed due to the increased cost of raw materials, competition within the trade, and the serious financial problems of John McDougall’s successor, George McDougall. Swank, writing in 1892 about “The First Iron Works in Canada,” states (n.d.: 351): “at the time of its abandonment in 1883 the St. Maurice furnace was the oldest active furnace on the American continent.

“The four archaeological periods at Les Forges can be related to the three periods of Canada’s political history — the New France period (1604-1760), the British North America period (1763-1867), and the first years ofDominion of Canada (post-1867). Briefly outlined below is the ironwork’s technological development.

I 1667-1760

1667 Iron ore discovered in the vicinity of Trois-Rivieres.

1672 Mining of ore started.

1730 Les Forges founded by royal commission.

1732-1734 Direct process copied from New England. Production of bloomery iron in the Catalan forge slightly exceeding nine kilograms per day. Total production of one tonof wrought iron.

1736 Blast furnace and two finery hearths (the lower forge)erected.

1738-1760 Indirect process in a charcoal blast furnace accompanied by two large forges. (Upper forge built in 1739.)Daily production 2.5 tons of cast iron. One of LesForges’ most successful periods of operation. Production of pots, kettles, stoves, cannons, mortars, andwrought-iron bars.

II 1760-1800

1760-1793 Intermittent operations.

Ill 1800-1850

1793-1846 Great prosperity in the first part and declining performance in the last part of this period.

1793-1815 Production of large potash kettles, heating stoves, ploughshares, cauldrons, “machines for mills,” anvils,tools, various kinds of castings, also wrought-iron barsand pig iron.

1820s Introduction of a cupola or air furnace; only small quantities of pig iron went for export.

IV 1850-1883

1846-1883 The final years, a period of technological change but only intermittent operation. Daily production rose to four to five tons after the renovation of the blast furnace, mainly by increasing its dimensions. A hot-blast stove and an air compressor were also introduced around the blast furnace.

1860s Production of wrought iron as well as of iron castings ceased completely.

1873-1883 Intermittent operations limited to production of cast iron shipped to Montreal to foundries making railroadcars.

1881 A second charcoal-fired blast furnace was built. It was of modern design with a hot blast and three water cooled tuyeres.

1883 Original blast furnace abandoned. Final closing of the ironworks.

Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia

Annapolis Royal is located in the western part of Annapolis County and was known as Port Royal until the British Conquest of Acadia in 1710 by Britain. The town was the capital of Acadia and later Nova Scotia for almost 150 years, until the founding of Halifax in 1749. It was attacked by the British six times before permanently changing hands in 1710. Over the next fifty years, the French and their allies made six unsuccessful military attempts to regain the capital. Including a raid during the American Revolution, Annapolis Royal faced a total of thirteen attacks, more than any other place in North America.

(Author Photos)

Bronze16-inch Smoothbore Muzzleloading Mortar, stamped No. 2, Serial No. 2006, with three fleur-de-lys. This Mortar stands beside the flag pole North of the main entrance.

LA RUGISSANT (The Roaring One)

(Author Photos)

Bronze 12-pounder 6-cwt Smoothbore Muzzleloading Gun, weight 6-0-17 (689 lbs), 3.75-inch, (Serial No. 278) above the cascabel. The first band is cast with “LA RUGISSANT” (the roaring one) at the top of the barrel, followed by a second band cast with the motto “ULTIMA RATIO REGNUM” (the Final Argument of Kings), with the device of King Louis XIV (the “Sun King”). (Louis had ordered this inscription was to be etched into the field pieces of all his armies). The third band is cast as “NEC PLURIBUS IMPAR” (Not unequal to many), followed by the weight, 6.0.17, and a fourth band cast as “A STRASBOURG PAR J BERENCE, 1738” (made at Strasbourg by J Berenger, 1738). (Serial No. 36) is on the left trunnion, (the letter P is stamped over 671) on the right trunnion. LA RUGISSANT rests on wood supports South of the former Officer’s Quarters of Fort Anne, Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia.

Campbellton, New Brunswick

Battle of the Restigouche

Guns from the 1760 wreck of the French Frigate Machault in the Restigouche River. In the autumn of 1759 New France was on the verge of capitulation to the British. Montreal, its morale at a low ebb owing to the recent surrender of Quebec City and Louisbourg, was rapidly running out of military supplies and funds and in desperate need of French assistance. After prolonged haggling between civilian businessmen and the state, a six-ship fleet was hastily assembled at Bordeaux and outfitted to sail for Canada. The flagship of the fleet was the Machault. It had been built in Bayonne, France, in 1757 as a 550-tonneaux merchant frigate and later converted to a 500-tonneaux frigate-at-war (Beattie 1968: 53). Initially armed with 26 guns, it could have carried as many as 32 on its last voyage. The original 1758 outfitting list (Compte de construction: 1758) includes, among other supplies, various weaponry items purchased for use by the ship and its company: 24 12-livre cannons for the deck, 2 six-livre cannons for the forecastle, 24 wooden gun carriages, 6 swivel guns, 800 12-livre cannonballs, and 120 hand grenades, as well as an unspecified number of muskets, pistols, sabres, boarding axes, and mitraille (the literal English translation of which is “shower”), which was small iron or lead balls for use in multiple-shot anti-personnel projectiles such as grape and cannister shot. It is not known what, if any, guns were added at the time of re-outfitting, nor the exact nature of the munition supplies for Canada.

On 11 April 1760, one day after leaving port, the fleet was scattered by two British ships, and only three ships, the Machault, Marquis de Malauze and Bienfaisant, were able to make contact and continue their journey. By mid-May the French had reached the Gulf of St. Lawrence, where they captured a British ship and learned that the British. had preceded them downriver. The decision was made to head for the safety of the Bay of Chaleur, where they arrived with a number of British ships they had captured en route. The French set up camp on the bank of the Restigouche River and dispatched a messenger to Montreal for instructions . The British response to news of their presence was decisive. A fleet commanded by Captain Byron, that included the 74 Gun ship-of-the-line HMS Fame, the 70 Gun HMS Dorsetshire, the 60 Gun HMS Achilles, and the 32 Gun frigate HMS Repulse, and the 20 Gun frigate HMS Scarborough, quickly set sail with orders to find and destroy the French ships. On 22 June the British contacted the enemy fleet. The French, retreating upriver, attempted to prevent the British ships from following by sinking small boats across the channel, and at strategic points set up shore batteries with weapons removed from their ships.

After approximately two weeks of manoeuvring and sporadic fighting, the final engagement occurred on 8 July 1760. When surrender became inevitable, Captain Giraudais of the Machault ordered all hands to remove as much cargo from the ships as possible. With a dwindling powder supply and with water in its hold, the Machault was defenceless and the order was given to abandon and scuttle it. The Bienfaisant suffered the same fate and later in the day the British boarded and burned the abandoned Marquis de Malauze. The Battle of Restigouche was a turning point in Canadian history. Montreal, denied its much-needed supplies and morale booster, now had neither the means nor the will to attempt to re-take Quebec City or properly defend itself. In short, the loss of the fleet contributed to the British conquest of New France (Beattie and Pothier 1977: 6).

During the summer of 1967 a brief survey of the Machault was carried out by the Archaeological Research Division of Parks Canada. In the winter of 1968-69 a comprehensive magnetometer survey preceded an extensive three-year underwater project lasting from the 1969 through the 1971 field seasons, which yielded the vast majority of recovered artifacts. The cutting and raising of some of the ship’s timber occurred in 1972, along with minor artifact recovery (see Zacharchuk and Waddell 1984). (“Artillery from the Machault, an 18th Century French Frigate”, by Douglas Bryce, Studies in Archaeology, Architecture and History, National Historic Parks and Sites Branch, Parks Canada, Environment Canada, 1984, Ottawa)

French Cast Iron 12-livre smoothbore muzzleloading cannon with a 5-inch bore (12.6-cm), with fleur-de-lys on the barrel and a large letter P on the cascable. This cannon was salvaged from the 1760 wreck of the French Frigate Machault in the Restigouche River. It is mounted on a British 24-pounder iron garrison carriage, and is placed in the No. 1 position (far right as you stand behind the guns), at Campbellton, New Brunswick.

French Cast Iron 12-livre smoothbore muzzleloading cannon with a 5-1/2-inch bore (14-cm), with anchors on the barrel, F on both trunnions. This cannon was salvaged from the 1760 wreck of the French Frigate Machault in the Restigouche River. It is mounted on a British 24-pounder iron garrison carriage, and is placed in the No. 3 position (far left as you stand behind the guns), at Campbellton, New Brunswick.

(Author Photo)

French Cast Iron 2-pounder Smoothbore Muzzleloading Gun, weight and trunnions corroded, Fort Gaspéreau, ca. 1751-1756, mounted on a wheeled wood carriage. Gift of Honourable Frank B. Black, Sackville, NB in 1936. Fort Beausejour, New Brunswick.

On display inside the Fort Beausejour Visitor Centre:

French Cast Iron 6-pounder Smoothbore Muzzleloading Gun, weight TBC, ca. 1732-1770, the only remaining gun of those used in the defence of Fort Beauséjour in 1755. Gift from Dr J.C. Webster in 1937.

French Cast Iron ½-pounder Smoothbore Muzzleloading Gun, used for the defence of blockhouses and other likely fortifications. Gift of W.L. Bidden, Moncton, NB.

(Author Photo)

Cast Iron 13-pouce Smoothbore Muzzleloading Mortar, 30.48-cm bore, ca. 1758, from Louisbourg, stamped C, 4338, 22, 1. This mortar is on display in the Canadian War Museum, Ottawa, Ontario.

Guns preserved in Fortress Louisbourg, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia.

Louisbourg, Fortress Louisbourg

Cast Iron 9-pounder Smoothbore Muzzleloading Guns, 9-feet long, 4-inch calibre (three).

Cast Iron Smoothbore Muzzleloading Guns, 5-inch calibre, 9-foot, 8-inch (two).

Cast Iron Smoothbore Muzzleloading Gun, 5.25-inch calibre, 9-foot, 8-inch.

Cast Iron Smoothbore Muzzleloading Guns, 5-inch calibre (three), 9-foot, 10-inch long guns

Cast Iron Smoothbore Muzzleloading Guns, 5.5-inch (two), 9-foot, 11-inch, 5,416 lb.

Cast Iron Smoothbore Muzzleloading Gun, 5.5-inch, 10-foot, 2-inch long.

Cast Iron 18-pounder Smoothbore Muzzleloading Guns, 10-foot, 6-inch long, 5,416 lb, 5-inch calibre, (four), one is broken at the muzzle, and one has a stainless steel sleeve.

Cast Iron 18-pounder Smoothbore Muzzleloading Guns, 10-foot, 6-inch long, 5.5-inch (five).

Cast Iron 18-pounder Smoothbore Muzzleloading Guns, 10-foot, 8-inch long, (two).

Cast Iron 18-pounder Smoothbore Muzzleloading Guns, 11-feet, 2-inch long, 6-inch calibre, (four), 5,417 lbs, 5,473 lbs, 5,527 lbs, 5,621 lbs, 5,675 lbs, 5,682 lbs, and 5,772 lbs.

In January of 1719, the number and type of cannon which were present in Louisbourg were listed as: nine 36 livre guns, ten 24 livre guns, twelve 18 livre guns, seven 12 livre guns, eight 8 livre guns, four 6 livre guns, nineteen unserviceable guns, and one 9-inch mortar. (Due to discrepancies in measurement between the English “pound” and the French “livre”, the two terms are not equivalent).

In the summer of 1744 there were 110 guns within the town itself, including six 18 livres on the King’s Bastion, ten 24 livres on the Dauphin Bastion, six 6 or 12 livre guns on the barbette facing Fauxbourg as well as three British bronze 6 livre guns facing the harbour. There were twenty-eight 36 livre guns on the Royal battery, thirty-two 24 livre guns on the Island Battery as well as two 9-inch bronze mortars. Twelve 36 livre guns and six 24 livre guns were mounted at Pièce de la Grave, and two 12-inch bronze mortars were placed at the Maurepas Bastion. The Queen’s Bastion was protected with 18 and 24 livre guns while the Princess Demi-Bastion relied on smaller 6 and 8 livre guns. Additional cannons were brought to the fortress from outlying settlements in 1758 and strategically spread throughout the town.

An unspecified number of cannon were also located along the north-east and south-west coast at places such as Flat Point, White Point, Kennington Cove, Lorraine and Black Rock. These pieces gave an approximate total of 168 cannons, plus an unspecified number of mortars. The cannon in use in Louisbourg were, for the most part, mounted on marine carriages. The mortar platforms were made from wood with iron fittings. All artillery pieces were applied with tar and red ochre paint for preservation.

The Fortress of Louisbourg has a number of reproduction cannons on display which were reproduced to French measure. These are distributed as close as possible to the artillery lists for 1744 for the area of the fortified town that has been reconstructed. As a result, there are six 18-livre guns in the King’s bastion, ten 24-livre guns in the Circular Battery enclosing the Dauphin demi-bastion, five 12-livre guns on the Dauphin demi-bastion and three 8-livre guns on the Quai walls. There are also several cannon barrels depicted as being “in store” outside the hangar d’artillerie in Block One. There are several breech-loading reproduction pedararos (swivel guns) on display in one of the warehouses.

The Parks Canada staff has an unidentified Bronze Coehorn smoothbore muzzleloading mortar included in an exhibit on the operation of a fortress and a reproduction Cast Iron Coehorn smoothbore muzzleloading mortar for use in their artillery animation program. There is also a small period gun on display in this exhibit. In the visitor reception centre there is a period French 18-livre gun and a large (probably 13 pouce) Cast Iron smoothbore muzzleloading mortar. This mortar is a twin to one on display in the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa. B.A. (Sandy) Balcom, Cultural Management Co-ordinator, Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Site.

(Doug Knight Photo)

Bronze possible 3-pounder Smoothbore Muzzleloading Gun, 42-mm bore, (Serial No. 738 on trunnions), unmounted, marked “DES INDES COMPAGNIE DE FRANCE”, “Fait par GOR a Paris 1732”. An old CWM Ledger from 1910 noted that this gun was used in the war between the English and French East India Companies 1746-1766. Unfortunately, there is no record of how it came to the Archives before it came to the Canadian War Museum. Doug Knight.

(Skeezix1000 Photo)

French SBML 12-pounder Guns (two), broken parts, trunnions missing. Two guns flank the West Entrance to the Whitney Block on Queen’s Park Circle in Toronto, Ontario. The guns were on the French naval ship Prudent, captured and burned by the British in June 1758 during the siege of Louisbourg. Twenty guns, from Prudent and other French ships sunk during the siege, were raised in 1899, two of which were acquired by the Government of Ontario.

(Author Photo)

SBML Gun, heavily corroded, mounted near the Plains of Abraham in Quebec. This gun is mounted on a 24-pounder iron carriage and has a cannon ball embedded in its muzzle. This gun was also recovered from the wreck of the French warship Prudent, which was captured and burned by the British in June 1758 during the siege of Louisbourg. It is one of the 20 guns raised in 1899 from the Prudent and other French ships sunk during the siege.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 2835894)

Wolfe wading ashore through the surf at Louisbourg, 1758.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 2264990)

Louisbourg view of the harbour, painted by Dennis Noble.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3305855)

Large 12-pounder smoothbore muzzleloading cannon at Louisbourg, photo taken in the early 1900s.

Large guns and mortars were put to good use in the two major sieges of the French fortress of Louisbourg at Cape Breton, Nova Scotia in 1745 and 1758. During the first siege, forces from New England landed 8 km southwest of Louisbourg at Gabarus Bay in a flanking manoeuvre and proceeded overland with their cannon on sleds. The French defenders of the strategically important Island Battery successfully stopped several assaults, inflicting heavy losses on the New England troops. However, the New Englanders eventually established gun batteries at Lighthouse Point that commanded the island, leading to its abandonment by its defenders. The New Englanders’ landward siege was supported by a fleet led by Commodore Warren and, following 47 days of siege and bombardment, the French surrendered Louisbourg on 28 June 1745.

When the war ended with the signing of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748, Louisbourg was returned to France in exchange for the return of Madras (capital of the Indian state of Tamil), to Britain, and the withdrawal of French troops from the Low Countries.[13]

French Land Service Mortar, ca. 1750, Fort Beauséjour, New Brunswick.

Fort Beauséjour sited on the present day New Brunswick border with Nova Scotia, was built by order of the Marquis de Jonquière, Governor of Canada, between 1750 and 1751. On 22 May 1755 a fleet of three warships and thirty-three transports carrying 2100 soldiers sailed from Boston, Massachusetts, landing at Fort Lawrence on 3 June 1755. The following day the British forces attacked Fort Beauséjour and on 16 June 1755 the French forces evacuated to Fort Gaspéreau, arriving on 24 June 1755 and onward to Fortress Louisbourg where they were re-garrisoned on 6 July 1755.

A number of guns and mortars may be viewed on the grounds of the present day fortress, located near Aulac, Westmorland, County, New Brunswick, formerly Sunbury County, Nova Scotia. A plaque on the site commemorates the fort’s history:

“Fort Beauséjour was taken by Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Monckton with volunteers from New England known as Shirley’s Regiment, raised by Lieutenant-Colonel John Winslow, aided by men of the Royal Artillery and other British troops after a siege lasting from 3 to 16 June 1755. Renamed Fort Cumberland, it was besieged again by rebels under Jonathan Eddy from 4 to 17 November 1775; defended by the Royal American Fencible Regiment under Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Gorham and relieved by Major Thomas Batt with a body of Royal Marines and Royal Highland Emigrants, who routed the besiegers.”[14]

Fort Cumberland was abandoned in the late 1780s. With the British resumption of hostilities with the United States in 1812, British forces reoccupied and refurbished the fort. Although it did not see any action during this conflict, the presence of a British garrison served as a deterrent to attack. In 1835 the British military declared the fort surplus property and it was abandoned until 1926 when the property was declared a National Historic Site by Canada.[15]

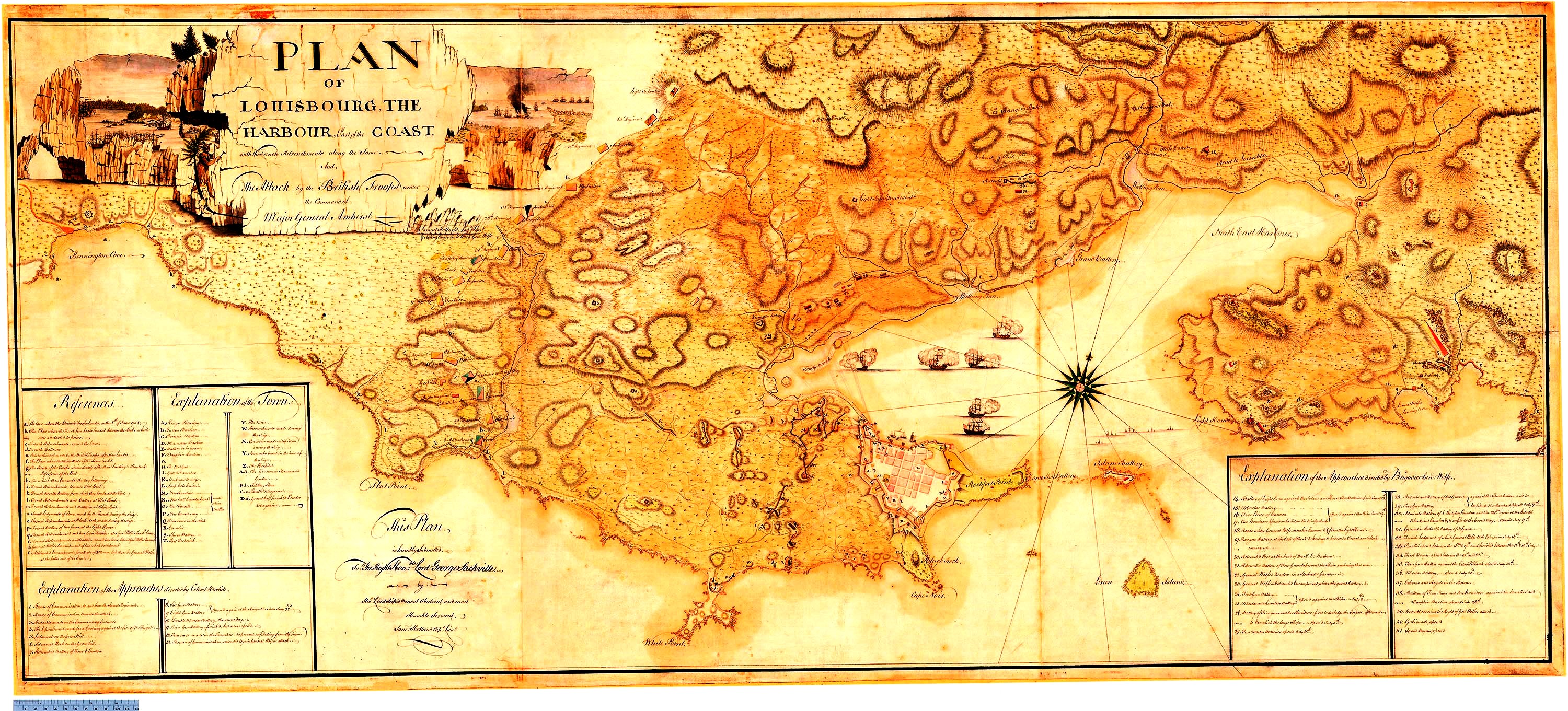

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 4151402)

Plan of Louisbourg, the harbour, part of the coast, with the French retrenchments along the same and the attack by the British troops under the command of Major General Amherst in1758. Cartographic material by Samuel Holland.

The British government realized that with the Fortress of Louisbourg under French control, it would be difficult for the Royal Navy to sail down the St. Lawrence River for an attack on Québec unmolested. Therefore, in 1758 the fortress of Louisbourg was assaulted and captured again by the British in a pivotal battle of the Seven Years’ War (also known as the French and Indian War). The British were fired upon by French gunners during their initial seaborne landings, as observed by General Jeffrey Amherst who who noted, “…the enemy…acted very wisely, did not throw away a shot until the boats were close in shore and then directed the whole of their fire of cannon and musquetry upon them.”[16]

General James Wolfe eventually got ashore and moved his British artillery batteries over land. On 19 June 1758, they were in position and the orders were given to open fire on the French. The British battery consisted of seventy cannon and mortars of all sizes. Within hours, the guns had destroyed walls and damaged several buildings. The French used twelve large Cast Iron or Bronze mortars with a 10-inch bore or larger and five smaller mortars in the town’s defence.[17]

On 21 July a mortar round from a British gun on Lighthouse Point struck a 74 gun French ship of the line, L’Entreprenant, and set it ablaze. A stiff breeze fanned the fire, and shortly after the L’Entreprenant caught fire, two other French ships had caught fire. L’Entreprenant exploded later in the day, depriving the French of the largest ship in the Louisbourg fleet. On the evening of 23 July a British “hot shot” set the King’s Bastion on fire. The King’s Bastion was the fortress headquarters and the largest building in North America in 1758. Its destruction eroded confidence and reduced morale in the French troops and their hopes to lift the British siege. Louisbourg held out long enough to prevent an attack on Québec in 1758, but in 1759, it too would fall. The capture of Louisbourg ended the French colonial era in Atlantic Canada and led directly to the loss of Québec in 1759 and the remainder of French North America the following year.[18]

When General Wolfe moved on from Louisbourg to Québec, he took some powerful artillery units with him, although they played only a small part in the final attack which was essentially an infantry battle. Montcalm’s forces were short of both powder and gunners but did manage to deploy at least four field guns. The British for their part had just two 6-pounder Guns in action on the Plains of Abraham on 13 September 1759. Siege guns were later brought up to the site of the battle and arrayed against the City just before it was surrendered.[19]

Following the surrender of Québec, an inventory of the gun batteries defending the city counted “180 pieces of Cannon” ranging in size from 2-pounder Guns to 36-pounder Guns, as well as 15 mortars ranging in size from 7-inches to 13-inches. Another 50 iron guns were found between the St. Charles and Montmorency Rivers.[20] When the Seven Years War ended, Île-Royale and much of New France was ceded to Britain under the terms of the 1763 Treaty of Paris.

The progressive development of guns in France continued with advances in technology being incorporated in new designs and often retrofitted in old guns. These improvements were necessary to counter those of other nations as the ability to rapidly strike one’s enemy out of his range or from an unexpected close range quarter became more important in determining the outcome of a battle.

(PHGCOM Photo)

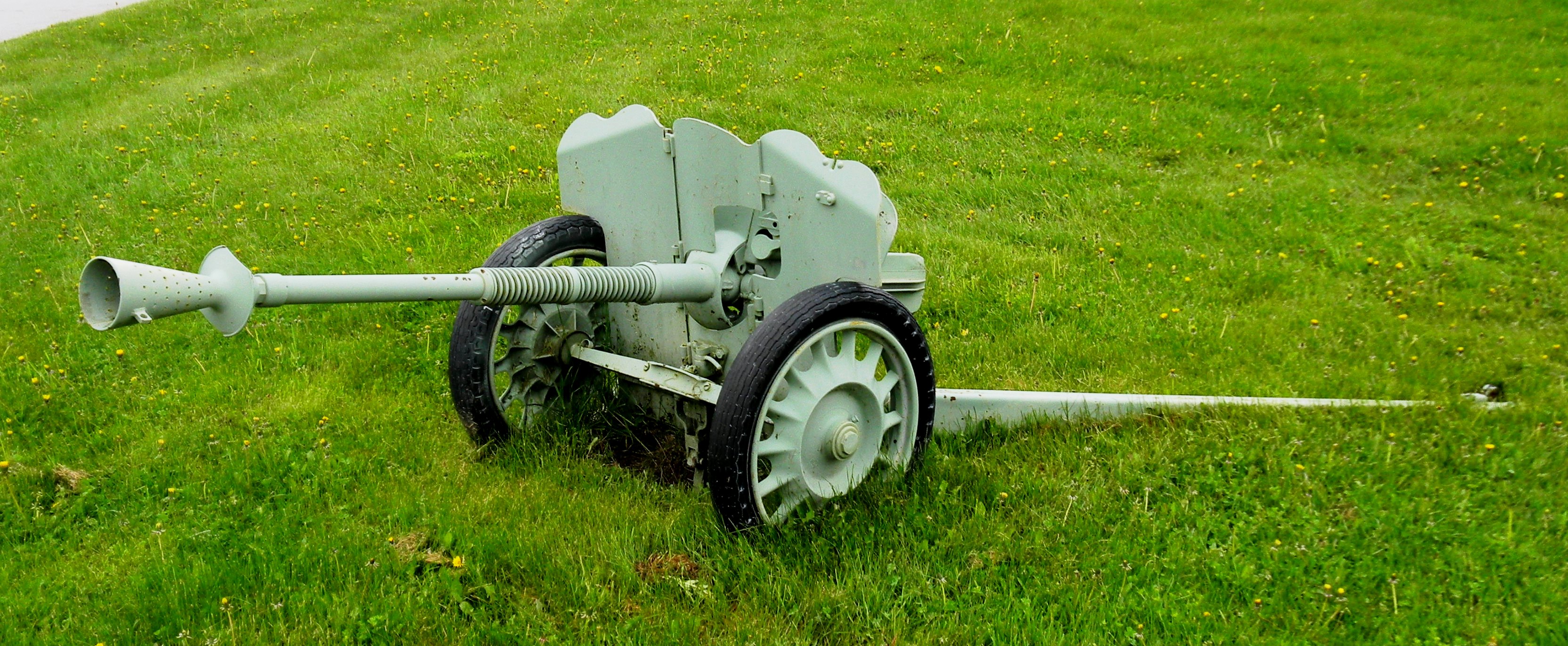

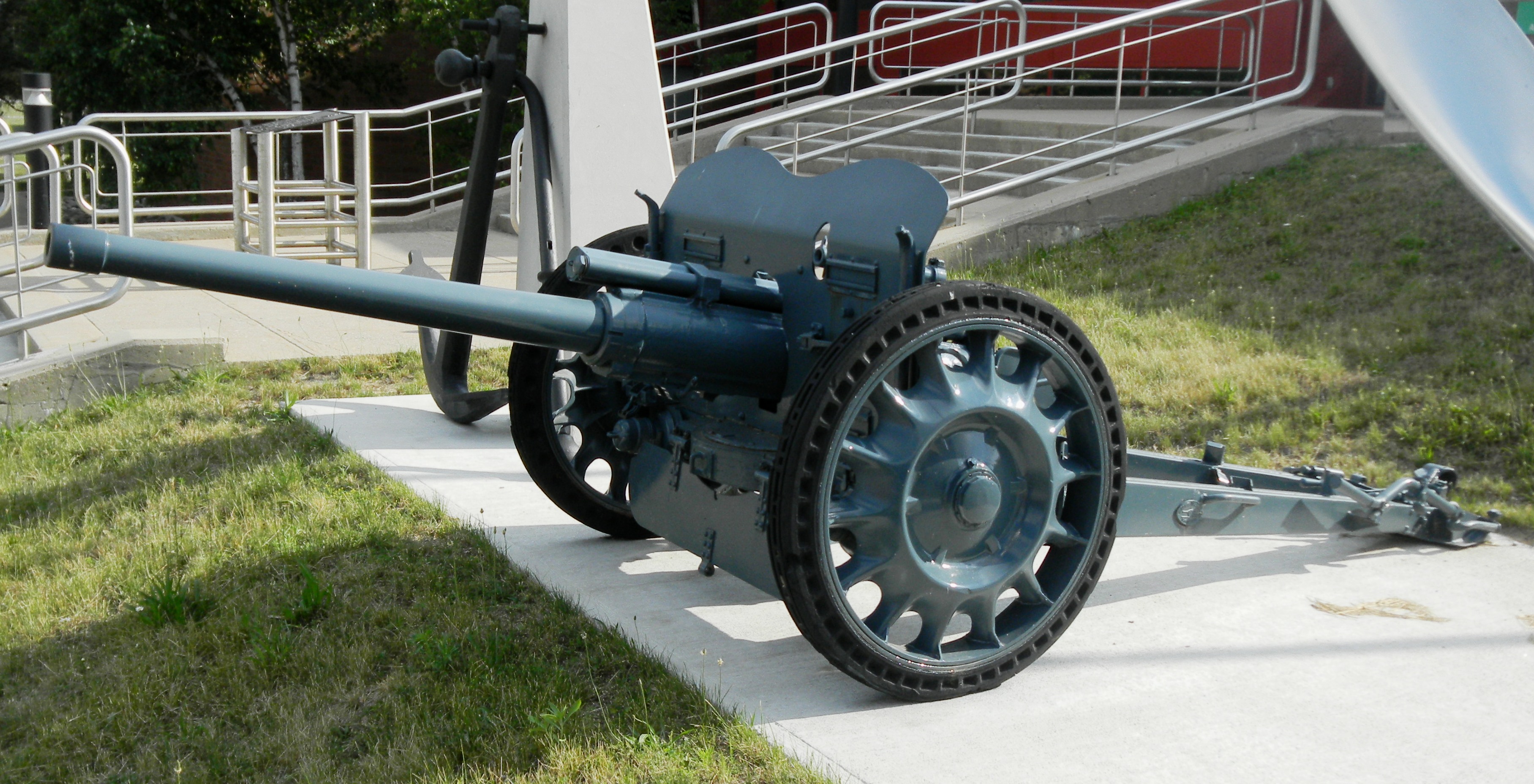

Siege operations involved heavy use of mortars, among other weapons of destruction. The Mortier de 12 pouces Gribeauval (Gribeauval 12-inch mortar) was a French mortar used as siege artillery and part of the Gribeauval system developed by Jean Baptiste Vaquette de Gribeauval.