Artillery in Portugal (Part 5), Marine Museum, Lisbon

The aim of this website is to locate, identify and document every historical piece of artillery preserved in Portugal. Many contributors have assisted in the hunt for these guns to provide and update the data found on these web pages. Photos are by the author unless otherwise credited. Any errors found here are by the author, and any additions, corrections or amendments to this list of Guns and Artillery in Portugal would be most welcome and may be e-mailed to the author at hskaarup@rogers.com.

Artilharia em Portugal (Parte 5)

Museu Marinho, Lisboa

O objetivo deste site é localizar, identificar e documentar cada peça histórica de artilharia preservada em Portugal. Muitos

colaboradores ajudaram na busca por essas armas para fornecer e atualizar os dados encontrados nessas páginas da web. As fotos são do autor, salvo indicação em contrário. Qualquer erro encontrado aqui é do autor e quaisquer acréscimos, correções ou alterações a esta lista de armas e artilharia em Portugal serão bem-vindos e podem ser enviados por e-mail ao autor em hskaarup@rogers.com.

Maritime Museum Artifacts, Lisbon, Portugal

The Maritime Museum is located on the Western end of the Monastery of Jerónimos, which is located North of the Tower of Belém. The monastery celebrates the return of Vasco da Gama and the riches he brought back from the East. On its western (left) side is a ships anchor and a wide concrete pavilion. The Maritime Museum is in two sections with the Galliot Pavilion, another exhibition wing of the Lisbon Maritime Museum on the opposite side of the Calouste Gulbenkian Planetarium. On the waterfront South of the Museum is the Discoveries Monument which was erected in 1960 to commemorate the death 500 years before of Henry the Navigator.

Cast Iron Mortar, No. 118, 9060, No. 1 of 2 at the museum entrance.

Cast Iron Mortar, No. 117, 9070, No. 2 of 2 at the museum entrance.

Early Portuguese Navy

The first known battle of the Portuguese Navy was in 1180, during the reign of Portugal’s first king, Afonso I of Portugal. The battle occurred when a Portuguese fleet commanded by the knight Fuas Roupinho defeated a Muslim fleet near Cape Espichel. He also made two incursions at Ceuta, in 1181 and 1182, and died during the last of these attempts to conquer Ceuta.

During the 13th century, in the Portuguese Reconquista, the Portuguese Navy helped in the conquest of several littoral moorish towns, like Alcácer do Sal, Silves and Faro. I t was also used in the battles against Castile through incursions in Galicia and Andalucia, and also in joint actions with other Christian fleets against the Muslims.

In 1317 King Denis of Portugal decided to give, for the first time, a permanent organization to the Royal Navy, contracting Manuel Pessanha of Genoa to be the first Admiral of the Kingdom. In 1321 the navy successfully attacked Muslim ports in North Africa.

Maritime insurance began in 1323 in Portugal, and between 1336 and 1341 the first attempts at maritime expansion are made, with the expedition to Canary Islands, sponsored by King Afonso IV.

At the end of the 14th century, more Portuguese discoveries were made, with the Navy playing a main role in the exploration of the oceans and the defense of the Portuguese Empire. Portugal became the first oceanic navy power.

Portuguese Naval Artillery

Naval artillery was the single greatest advantage the Portuguese held over their rivals in the Indian Ocean – indeed over most other navies – and the Portuguese crown spared no expense in procuring and producing the best naval guns European technology permitted.

King John II of Portugal is often credited for pioneering, while still a prince in 1474, the introduction of a reinforced deck on the old Henry-era caravel to allow the mounting of heavy guns. In 1489, he introduced the first standardized teams of trained naval gunners (bombardeiros) on every ship, and development of naval tactics that maximized broadside cannonades rather than the rush-and-grapple of Medieval galleys.

The Portuguese crown appropriated the best cannon technology available in Europe, particularly the new, more durable and far more accurate bronze cannon developed in Central Europe, replacing the older, less accurate cast-iron cannon. By 1500, Portugal was importing vast volumes of copper and cannon from northern Europe, and had established itself as the leading producer of advanced naval artillery in its own right. Being a crown industry, cost considerations did not curb the pursuit of the best quality, best innovations and best training. The crown paid wage premiums and bonuses to lure the best European artisans and gunners (mostly German) to advance the industry in Portugal. Every cutting-edge innovation introduced elsewhere was immediately appropriated into Portuguese naval artillery – that includes bronze cannon (Flemish/German), breech-loading swivel-guns (prob. German origin), truck carriages (possibly English), and the idea (originally French, c. 1501) of cutting square gunports (portinhola) in the hull to allow heavy cannon to be mounted below deck.

In this respect, the Portuguese spearheaded the evolution of modern naval warfare, moving away from the Medieval warship, a carrier of armed men, aiming for the grapple, towards the modern idea of a floating artillery piece dedicated to resolving battles by gunnery alone.

According to Gaspar Correia, the typical fighting caravel of Gama’s 4th Armada (1502) carried 30 men, four heavy guns below, six falconets (falconete) above (two fixed astern) and ten swivel-guns (canhão de berço) on the quarter-deck and bow.

An armed carrack, by contrast, had six heavy guns below, eight falconets above and several swivel-guns, and two fixed forward-firing guns before the mast. Although an armed carrack carried more firepower than a caravel, it was much less swift and less manoeuvrable, especially when loaded with cargo. A carrack’s guns were primarily defensive, or for shore bombardments, whenever their heavier firepower was necessary. But by and large, fighting at sea was usually left to the armed carvels.

The development of the heavy galleon removed even the necessity of bringing carrack firepower to bear in most circumstances. One of them became famous in the conquest of Tunis and could carry 366 bronze cannons, for this reason, it became known as Botafogo, meaning literally fire maker, torcher or spitfire in popular Portuguese

Military personnel aboard a nau varied with the mission. Except for some specialists and passengers, most of the crew was armed before encounters and expected to fight. But every nau also had, at the very least, a small specialized artillery crew of around ten bombardeiros (gunners), under the command of a condestável (constable). As naval artillery was the single most important advantage the Portuguese had over rival powers in the Indian Ocean, gunners were highly trained and enjoyed a bit of an elite status on the ship. (Indeed, many gunners on Portuguese India ships were highly skilled foreigners, principally Germans, lured into Portuguese service with premium wages and bonuses offered by crown agents. Ships that expected more military encounters might also carry homens d’armas (men-at-arms), espingardeiros (arquebusiers/musketeers) and besteiros (crossbowmen). But, except for the gunners, soldiers aboard ship were not regarded as an integral part of the naval crew, but rather just as passengers. Internet: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portuguese_India_Armadas.

(manchanegra Photos)

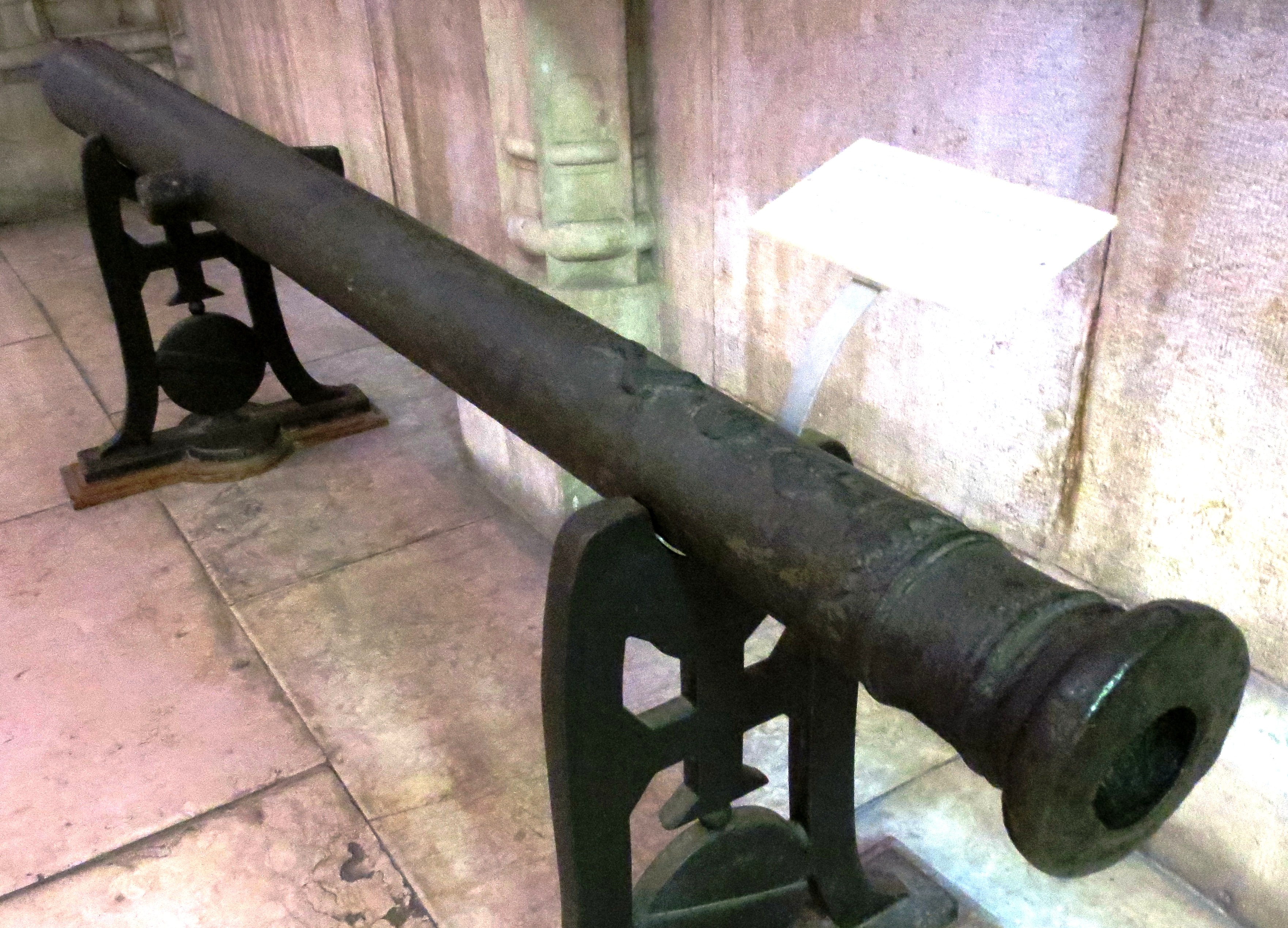

Bronze 9-cm Smoothbore Muzzleloading Gun cast in Portugal in the 17th century, recovered from the Sea of Sines (Portugal) in 1972.

Bronze Falcon, cast in the 16th century, firing a shot of 2 Arrateis (approximately 1 kilogram).

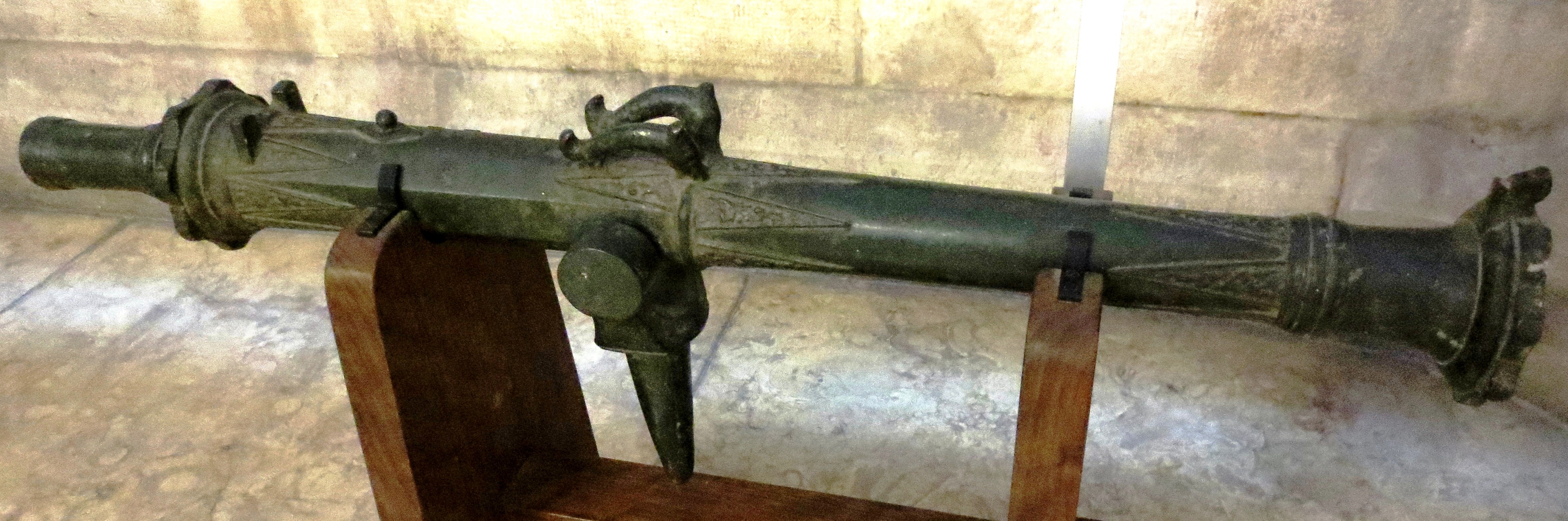

Falconet breech-loading 110-mm bronze smoothbore gun, cast in Portugal during the reign of D. Sebastiao, ca 17th century. This gun fired iron or lead shot to a range of nearly 2 km. It bears the arms of Porftugal, an armilary sphere and the cypher of D. Sebastiao. It is located close to the main entrance of the Maritime Museum.

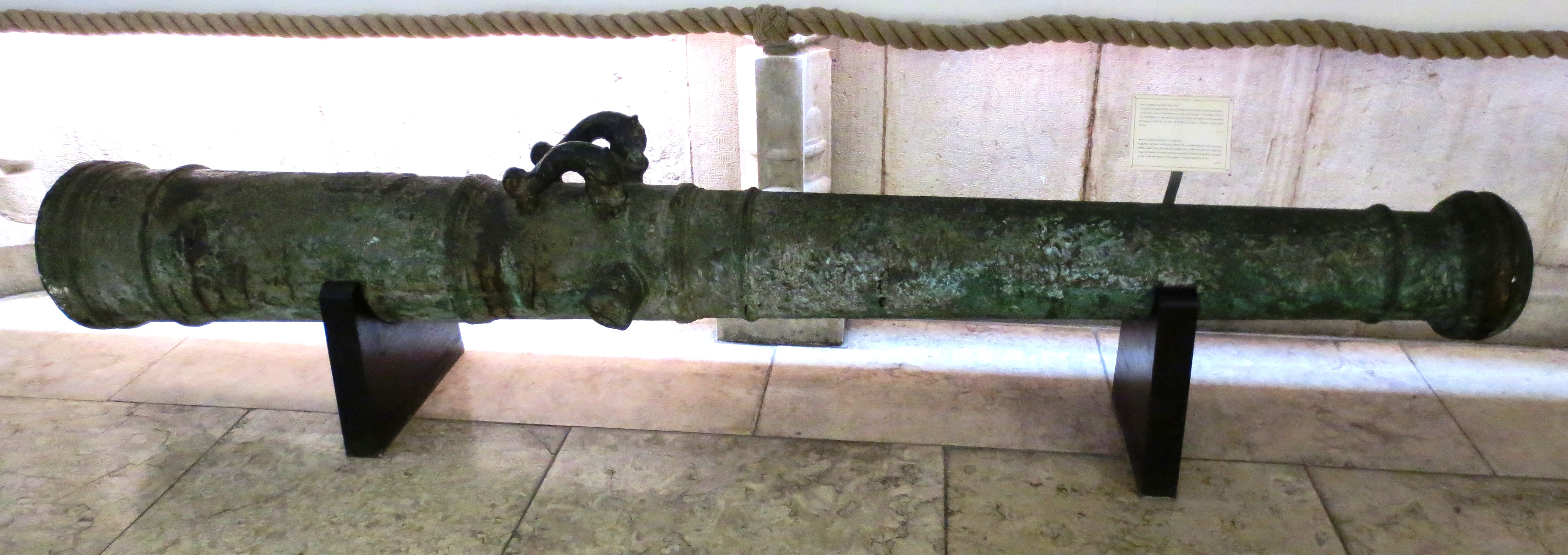

Bronze Smoothbore Muzzleloading Meia Colubrina Bastarda, 17th century Gun with dolphin handles, probably Portuguese (from the Philippine dynasty). The Bastarda barrel length was less that 30 calibres and it fired a 6 kg (12 lb) iron shot. This cannon was recovered off the beach at Porto das Barcas, Lourinha in 1968, fron the Galleon S. Nicolau which was wrecked in 1642. It is located close to the entrance to the Maritime Museum.

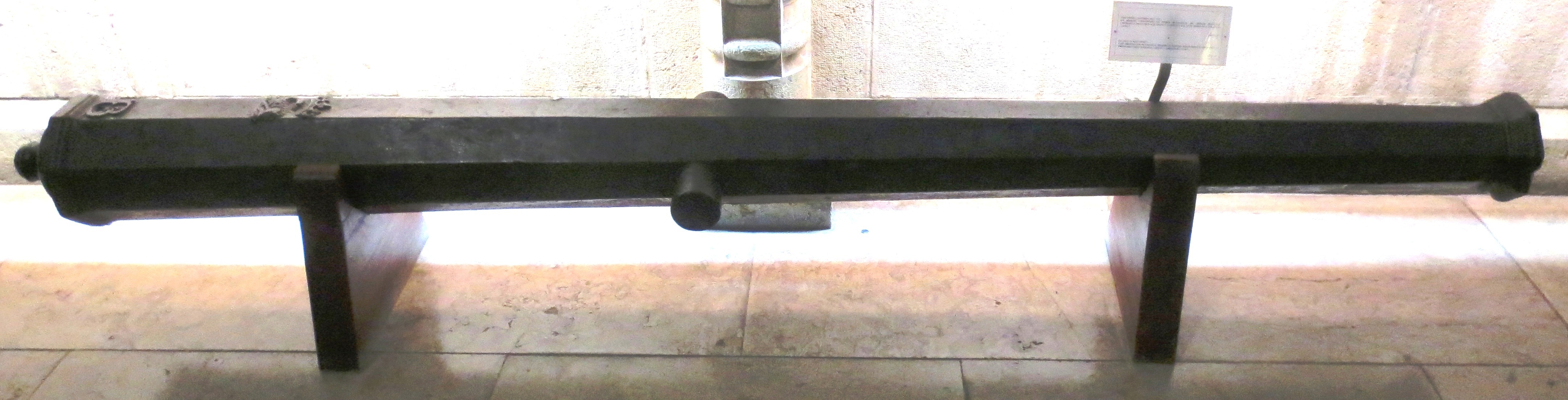

Bronze 52-mm Breechloading Manueline Gun, cast in Portugal probably during the reign of D. Joao III between 1521 and 1557. The gun is decorated with the Arms of Portugal and the Armillary Sphere. It was recovered 1985, from the Santiago, which was wrecked on the shallows of Judia in the Straits of Mozambique in 1585.

Falcon (16th Century) octogonal shaped bronze gun cast in France in the reign of King D. Francisco I. This gun fires an iron shot with a 1.4 kg (3 lb) weight. It is one of the first guns on display inside the main entrance to the Maritime Museum.

Bronze 12-pounder Smoothbore Muzzleloading Gun of Swedish origin (17th century). This gun’s bore has been recalibrated with iron. It was most likely part of the ordnance of the Fort of Bugio on the Tagus River.

Bronze Smoothbore Muzzleloading Lantaca Gun (18th century), with dolphin carrying handles, originally from the Far East. These guns were usually fitted on the gunwales of ships and were cast in Portugal as well as other European countries, Thus gun is also located near the entrance to the Maritime Museum.

Bronze Smoothbore Muzzleloading Bastard demi-culverin Gun with dolphin carrying handles, cast in Portugal in the 17th century, probably during the reign of Filipe II. The gun bears the arms of Portugal and the collar of the Order of Tosao de Oiro. It was probably taken from the bastions of the Fortress of Diu, India. On display in the Maritime Museum.

Bronze Smoothbore Muzzleloading Lantica Naval Gun, (18th/19th century), originally from the Far East. These guns were usually fitted on the gunwales of ships and were cast in Portugal and other European countries. This gun is on display in the Maritime Museum.

Bronze 77-mm Smoothbore Muzzleloading Gun cast in Holland in 1737 by Ciprianus Cranz for Portugal in the reign of D. Joao V. The gun has highly ornamented and a large royal coat of arms cypher. This gun is on display inside the Maritime Museum.

Portuguese 8-cm bronze rifled gun cast by the Army Ordnance in 1862. At the end of the 19th century this gun was used in the Portuguese campaigns in Africa in support of the Naval forces fighting on land. This gun is on display in the Maritime Museum.

5-1/2 lb Bronze Field Mortar cast in the Arsenal of the Portuguese Army in the 18th century.

17-cm Bronze Field Mortar cast in Barcelona, Spain in 1795.

Bronze 24-pounder Smoothbore Muzzleloading Gun with dolphin carrying handles mounted on a 24-pounder iron carriage. This gun was cast in Holland in 1737. It bears the Coat of Arms of King Joao V. This gun with its mounting originally belonged to the Tower of Bugio, located at the mouth of the Tagus River.

Bronze 8-cm rifled field gun mounted on a Naval carriage. This gun was cast by Portuguese Army Ordnance in 1868. At the end of the 19th century in was used in the Portuguese African campaigns in support of Naval forces fighting on land.

11.4-mm Maxim-Nordenfeldt Model 1889 machine-gun, (Serial No. 1347).

6.5-mm Hotchkiss Model 1895 machine-gun (Serial No. 15141), No. 198, 1899, used by the Portuguese Navy.

37-mm five-barrel Hotchkiss revolving gun, Model 1890.

Cast Iron Smoothbore Muzzleloading Gun mounted on a wood Naval gun carriage, No. 542 on the cascabel. It appears to be from the late 19th century, No. 1 standing right side of the exit from the Maritime Museum.

Cast Iron Smoothbore Muzzleloading Gun, gun manufacturers symbol over P on the barrel, mounted on a wood Naval gun carriage. It appears to be from the late 19th century, No. 2 standing left side of the exit from the Maritime Museum.

Armstrong-Woolwich 7-inch Muzzle-loading Naval Pivot Gun with three rifling grooves, model display.

Naval aircraft on display in the museum.

Fairey IIID floatplane inside the museum. This aircraft, named “Santa Vruz” took part in the first air-crossing of the South Atlantic in June 1922.

Fairey IIID floatplane bronze replica on display on the Tagus riverfront near the museum.

Historic seaplane inside the museum.

Grumman G44 Widgeon inside the museum.

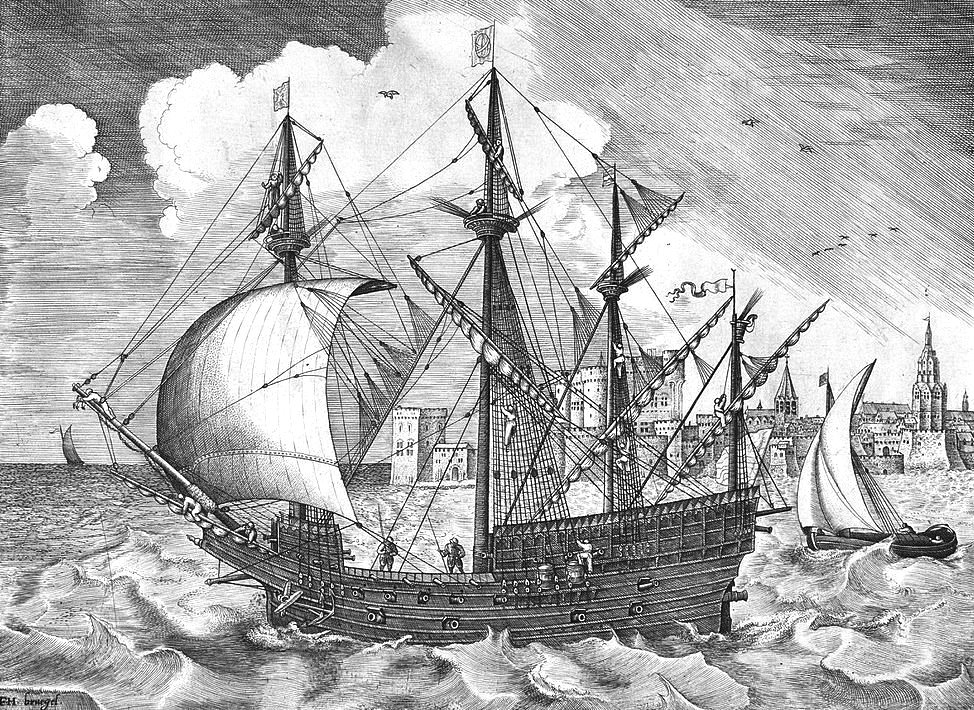

Engraving of a Portuguese carrack, by Frans Huys circa 1555. Identifiable by the armillary sphere it flies as a banner.

The Portuguese Indian Armadas (Armadas da Índia) were the fleets of ships, organized by the crown of the Kingdom of Portugal and dispatched on an annual basis from Portugal to India, principally to Portuguese Goa and other colonies such as Damaon. These armadas undertook the Carreira da Índia (“India Run”), following the sea route around the Cape of Good Hope first opened up by Vasco da Gama in 1497–1499. Between 1497 and 1650, there were 1033 departures of ships at Lisbon for the Carreira da Índia (“India Run”). Guinote, P.J.A. “Ascensão e Declínio da Carreira da Índia“, Vasco da Gama e a Índia, Lisboa. (Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Vol, II, 1999)

Setting out from Lisbon (February–April), India-bound naus took the easy Canary Current straight southwest to the Canary Islands. The islands were owned by Castile and so this was not a usual watering stop for the Portuguese Indian armadas, except in emergencies.

With the monsoon, Portuguese Indian armadas usually arrived in India in early September (sometimes late August). Because of the wind pattern, they usually made landfall around Anjediva island (Angediva). From there, the armada furled their square sails and proceed with lateen sails south along the Malabar coast of India to the city of Cochin (Cochim, Kochi) in Kerala. Cochin was the principal spice port accessible to the Portuguese, it had the earliest Portuguese factory and fort in India and served as the headquarters of Portuguese government and operations in India for the first decades. However, this changed after the Portuguese conquest of Goa in 1510. The capture of Goa had been largely motivated by the desire to find a replacement for Anjediva as the first anchoring point for the armadas. Anjediva had proven itself to be far from ideal. The island was generally undersupplied – it contained only a few fishing villages – but the armada ships were often forced to sojourn there for long periods, usually for repair or to wait for better winds to carry them down to Cochin. Anjediva island also lay in precarious pirate-infested waters, on the warring frontier between Muslim Bijapur and Hindu Vijaynagar, which frequently threatened it. The same winds which carried the armada down to Cochin prevented Portuguese squads from Cochin racing up to rescue it. The Portuguese had tried setting up a fort in Anjediva, but it was captured and dismantled by forces on behalf of Bijapur. As a result, the Portuguese governor Afonso de Albuquerque decided the nearby island-city of Goa was preferable and forcibly seized it in 1510. Thereafter Goa, with its better harbor and greater supply base, served as the first anchorage point of Portuguese armadas upon arriving in India. Although Cochin, with its important spice markets, remained the ultimate destination, and was still the official Portuguese headquarters in India until the 1530s, Goa was more favorably located relative to Indian Ocean wind patterns and served as its military-naval center. The docks of Goa were soon producing their own carracks for the India run back to Portugal and for runs to further points east. Alexander Marchant, Colonial Brazil as a Way Station for the Portuguese India Fleets. (Geographical Review, Vol. 31, No. 3, 1941)

The size of the armada varied, from enormous fleets of over twenty ships to small ones as little as four. This changed over time. In the first decade (1500–1510), when the Portuguese were establishing themselves in India, the armadas averaged around 15 ships per year. This declined to around 10 ships in 1510–1525. From 1526 to the 1540s, the armadas declined further to 7-8 ships per year — with a few exceptional cases of large armadas (e.g., 1533, 1537, 1547) brought about by military exigency, but also several years of exceptionally small fleets. In the second half of the 16th century, the Portuguese Indian armada stabilized at 5-6 ships annually, with very few exceptions (above seven in 1551 and 1590, below 4 in 1594 and 1597). Guinote, P.J.A.

The ships of an India armada were typically carracks (naus), with sizes that grew over time. The first carracks were modest ships, rarely exceeding 100-tonnes, carrying only up to 40–60 men, e.g., the São Gabriel of da Gama’s 1497 fleet, one of the largest of the time, was only 120 t. But this was quickly increased as the India run got underway. In the 1500 Cabral armada, the largest carracks, Cabral’s flagship, and the El-Rei, are reported to have been somewhere between 240 t and 300 t. The Flor de la Mar, built in 1502, was a 400 t nau, while at least one of the naus of the Albuquerque armada of 1503 is reported to have been as large as 600 t. The rapid doubling and tripling of the size of Portuguese carracks in a few years reflected the needs of the India runs. The rate of increase tapered off thereafter. For much of the remainder of the 16th century, the average carrack on the India run was probably around 400 t.

In the 1550s, during the reign of John III, a few 900 t behemoths were built for India runs, in the hope that larger ships would provide economies of scale. The experiment turned out poorly. Not only was the cost of outfitting such a large ship disproportionately high, but they also proved unmaneouverable and unseaworthy, particularly in the treacherous waters of the Mozambique Channel. Three of the new behemoths were quickly lost on the southern African coast – the São João (900 t, built 1550, wrecked 1552), the São Bento (900 t, built 1551, wrecked 1554) and the largest of them all, the Nossa Senhora da Graça (1,000 t, built 1556, wrecked 1559). Mathew, K.N. History of the Portuguese Navigation in India. (New Delhi: Mittal, 1988)

The Madre de Deus, built in 1589, was a 1600 t carrack, with seven decks and a crew of around 600. It was the largest Portuguese ship to go on an India run. The great carrack, under the command of Fernão de Mendonça Furtado, was returning from Cochin with a full cargo when it was captured in August 1592 by the English privateer Sir John Burroughs (alt. Burrows, Burgh) in the waters around the Azores islands (Battle of Flores). The value of the treasure and cargo taken on this single ship is estimated to have been equivalent to half the entire treasury of the English crown. Castro, Filipe Vieira de. The Pepper Wreck: a Portuguese Indiaman at the mouth of the Tagus river. (College Station, TX: Texas A & M Press, 2005)

Naval Artillery

Naval artillery was the single greatest advantage the Portuguese held over their rivals in the Indian Ocean – indeed over most other navies – and the Portuguese crown spared no expense in procuring and producing the best naval guns European technology permitted.

King John II, while still a prince in 1474, is often credited for pioneering the introduction of a reinforced deck on the old Henry-era caravel to allow the mounting of heavy guns. In 1489, he introduced the first standardized teams of trained naval gunners (bombardeiros) on every ship, and development of naval tactics that maximized broadside cannonades rather than the rush-and-grapple of Medieval galleys.

The Portuguese crown appropriated the best cannon technology available in Europe, particularly the new, more durable, and far more accurate bronze cannon developed in Central Europe, replacing the older, less accurate wrought-iron cannon. By 1500, Portugal was importing vast volumes of copper and cannon from northern Europe and had established itself as the leading producer of advanced naval artillery in its own right. Being a crown industry, cost considerations did not curb the pursuit of the best quality, best innovations, and best training. The crown paid wage premiums and bonuses to lure the best European artisans and gunners (mostly German) to advance the industry in Portugal. Every cutting-edge innovation introduced elsewhere was immediately appropriated into Portuguese naval artillery – that includes bronze cannon (Flemish/German), breech-loading swivel-guns (prob. German origin), truck carriages (possibly English), and the idea (originally French, c. 1501) of cutting square gun ports (portinhola) in the hull to allow heavy cannon to be mounted below deck.

In this respect, the Portuguese spearheaded the evolution of modern naval warfare, moving away from the Medieval warship, a carrier of armed men, aiming for the grapple, towards the modern idea of a floating artillery piece dedicated to resolving battles by gunnery alone.

According to Gaspar Correia, the typical fighting caravel of Gama’s 4th Armada (1502) carried 30 men, four heavy guns below, six falconets (falconete) above (two fixed astern) and ten swivel-guns (canhão de berço) on the quarter-deck and bow.

An armed carrack, by contrast, had six heavy guns below, eight falconets above and several swivel-guns, and two fixed forward-firing guns before the mast. Although an armed carrack carried more firepower than a caravel, it was much less swift and less manoeuvrable, especially when loaded with cargo. A carrack’s guns were primarily defensive, or for shore bombardments, whenever their heavier firepower was necessary. But by and large, fighting at sea was usually left to the armed caravels. The development of the heavy galleon removed even the necessity of bringing carrack firepower to bear in most circumstances. Rodrigues, J.N. and T. Devezas. Portugal: o pioneiro da globalização : a Herança das descobertas. (Lisbon: Centro Atlantico, 2009)

According to historian Oliveira Martins, of the 806 naus sent on the India Run between 1497 and 1612, 425 returned safely to Portugal, 20 returned prematurely (i.e., without reaching India), 66 were lost, 4 were captured by the enemy, 6 were scuttled and burnt, and 285 remained in India (which went on to meet various fates of their own in the East.)

The loss rate was higher in certain periods than others, reflecting greater or lesser attention and standards of shipbuilding, organization, supervision, training, etc. which reveals itself in shoddily built ships, overloaded cargo, incompetent officers, as well as the expected higher dangers of wartime. The rates fluctuated dramatically. By one estimate, in 1571–1575, 90% of India ships returned safely; by 1586–1590, the success rate fell to less than 40%; between 1596 and 1605, the rate climbed above 50% again, but in the subsequent years fell back to around 20%. Guinote, P.J.A.

That only four ships on India runs were known to be captured by the enemy seems quite astonishing.

These were:

(1) 1508, the ship of Jó Queimado, originally part of the 8th Portuguese India Armada (Cunha, 1506) of Tristão da Cunha that set out in 1506. It was captured in 1508 by the French corsair Mondragon (said by one account to be in the Mozambique Channel, but it is unlikely Mondragon would have taken the trouble of doubling the Cape; it was more likely captured on the Atlantic side, probably near the Azores). Mondragon was himself tracked down and taken prisoner by Duarte Pacheco Pereira in January 1509, off Cape Finisterre.

(2) 1525, Sanata Caterina do Monte Sinai, the great carrack built in Goa in 1512. It had been used to carry Vasco da Gama in 1523 to serve as the new viceroy of India and was on its way back to Portugal in 1525, with the former governor D. Duarte de Menezes, when it was taken by French corsairs. (However, some have speculated that there was no foreign attack, that Menezes himself simply decided to go piratical and took command of the ship.)

(3) 1587, São Filipe, returning from an India run, was captured by English privateer Sir Francis Drake, off the Azores. The triumph of the São Filipe cargo, one of the wealthiest hoards ever captured, was overshadowed only by the even wealthier trove of paperwork and maps detailing the Portuguese trade in Asia which fell into English hands. This set in motion the first English expedition to India, under Sir James Lancaster in 1591.

(4) 1592 Madre de Deus, the gigantic carrack captured by Sir John Burroughs near the Azores, already described above.

This does not count ships that were attacked by enemy action and subsequently capsized or destroyed. It also does not count ships that were captured later in the East Indies (i.e., not on the India route at the time). The most famous of these was probably the mighty Portuguese carrack Santa Caterina (not to be confused with its earlier Mount Sinai namesake), captured in 1603, by Dutch captain Jacob van Heemskerk. The Santa Catarina was on a Portuguese Macau to Portuguese Malacca run with a substantial cargo of Sino-Japanese wares, most notably a small fortune in musk, when it was captured by Heemskerk in Singapore. The captured cargo nearly doubled the capital of the fledgling Dutch East India Company, officially the United East India Company Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC).

Ship losses should not be confused with crew losses from disease, deprivation, accident, combat, and desertion. These tended to be horrifically high – one third, or even as much as one half, even in good years. Guinote, P.J.A.

Military personnel aboard a nau varied with the mission. Except for some specialists and passengers, most of the crew was armed before encounters and expected to fight. But every nau also had, at the very least, a small, specialized artillery crew of around ten bombardeiros (gunners), under the command of a condestável (constable). As naval artillery was the single most important advantage the Portuguese had over rival powers in the Indian Ocean, gunners were highly trained and enjoyed a bit of an elite status on the ship. (Indeed, many gunners on Portuguese India ships were highly skilled foreigners, principally Germans, lured into Portuguese service with premium wages and bonuses offered by crown agents.)

Ships that expected more military encounters might also carry homens d’armas (men-at-arms), espingardeiros (arquebusiers/musketeers) and besteiros (crossbowmen). But, except for the gunners, soldiers aboard ship were not regarded as an integral part of the naval crew, but rather just as passengers. Rodrigues, J.N. and T. Devezas . Portugal: o pioneiro da globalização : a Herança das descobertas. (Lisbon, Centro Atlantico, 2009)