Black Military History in Canada’s Maritime Provinces

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3194350)

Three West Indian soldiers in a German dugout captured during the Canadian advance east of Arras, France in October 1918.

Black Military History in the Maritimes

The tradition of military service by black Canadians goes back long before Confederation. Many black Canadians can trace their family roots to Loyalists who emigrated North in the 1780s after the American Revolutionary War. American slaves had been offered freedom and land if they agreed to fight in the British cause and thousands seized this opportunity to build a new life in British North America.

The first recorded black person to arrive in Canada was an African named Mathieu de Coste who arrived in 1608 to serve as interpreter of the Mi’kmaq language to the governor of Acadia.

Richard Pierpoint, born around 1745 in the West African kingdom of Bondu, was a slave who served for the British army in 1776 to fight the Americans. In exchange for his service, freedom was granted if he survived. Pierpoint survived and was evacuated to Upper Canada as a free man. When the War of 1812 began, Pierpoint created the Coloured Corps of Upper Canada – a regiment that participated in important battles and were upgraded from infantry to “artificers” – an elite branch of the Royal Engineers. The regiment disbanded in 1815 but was revived in 1837, officially ending in 1851.

About 3,300 black loyalists arrived in Saint John in the mid-1780s, after the American Revolutionary War. They had been promised land grants in exchange for their service in the British army. When that land didn’t materialize, many left.

The New Brunswick community of Beaver Harbour was settled by Quaker loyalists. It was the first place in British North America, in 1783, to declare that slave owners were not welcome there. The tiny fishing community near Black’s Harbour now has a stone monument to mark that distinction and a replica of the community’s Quaker meeting house stands in the Beaver Harbour Quaker burial ground.

Thomas Peters, a leader among the black loyalists, petitioned colonial officials for several years on behalf of his people, before joining forces with a British company working to establish a colony of free blacks in Africa. Peters helped recruit 17 boatloads of people who migrated from the Maritimes to Africa in 1792. He is considered one of the founders of the nation of Sierra Leone.

In 1793, the Upper Canada legislature passed an act that granted gradual abolition and any slave arriving in the province was automatically declared free. Fearing for their safety in the United States after the passage of the first Fugitive Slave Law in 1793, over 30,000 slaves came to Canada via the Underground Railroad until the end of the American Civil War in 1865. They settled mostly in southern Ontario, but some also settled in Quebec and Nova Scotia.

Politically, the black Loyalist communities in both Nova Scotia and Upper Canada were characterized by what the historian James Walker called “a tradition of intense loyalty to Britain” for granting them freedom and Canadian blacks tended to be active in the militia, especially in Upper Canada during the War of 1812 as the possibility of an American victory would also mean the possibility of their re-enslavement.

The tradition of black soldiers in military service in North America did not end with the Revolutionary War, with some seeing action in the War of 1812, helping defend Upper Canada against American attacks. Several volunteers were organized into the “Company of Coloured Men,” which played an important role in the Battle of Queenston Heights and the siege of Fort George. Black militia members also fought in many other significant battles during the war, helping drive back the American forces and defending what would become Canada from the invading American army. Black soldiers also played an important role in the Upper Canadian Rebellion (1837–1839). In all, approximately 1,000 black militia men fighting in five companies helped put down the uprising, taking part in some of the most important incidents such as the Battle of Toronto.

After the War of 1812, 371 black refugees, many who had been slaves, travelled to Saint John on HMS Regulus. It arrived on 25 May 1815. (HMS Regulus was a fifth rate frigate of 44 guns, launched at Northam, England, in January 1785 and converted to a troopship in 1793. HMS Regulus was broken up in March 1816).

Willow Grove is one of the communities outside Saint John settled by black refugees who arrived after the war of 1812. A large white cross at the corner of Base Road and St. Martins Road marks the community, a burial ground and a former church. Gordon House, located at the King’s Landing Historical Settlement tourist park, is a replica of a house built by black New Brunswicker James Gordon in the nineteenth century on Dunn’s Crossing Road in Fredericton. Gordon is believed to be the child of black loyalists or slaves who came with white loyalists.

From the late 1820s, through the time that the United Kingdom forbade slavery in 1833, until the American Civil War began in 1861, the Underground Railroad brought tens of thousands of fugitive slaves to Canada. In 1819, Sir John Robinson, the Attorney-General of Upper Canada, ruled: “Since freedom of the person is the most important civil right protected by the law of England…the negroes are entitled to personal freedom through residence in Upper Canada and any attempt to infringe their rights will be resisted in the courts”. After Robinson’s ruling in 1819, judges in Upper Canada refused American requests to extradite run-away slaves who reached Upper Canada under the grounds “every man is free who reaches British ground”.

Following the abolition of slavery in the British empire in 1834, any black man born a British subject or who become a British subject was allowed to vote and run for office, provided that they owned taxable property. The property requirement on voting in Canada was not ended until 1920.

Tomlinson Lake in a rural area near the American border and Perth-Andover is believed to be the northernmost route on the Underground Railroad, by which people escaped slavery in the United States to freedom in Canada.

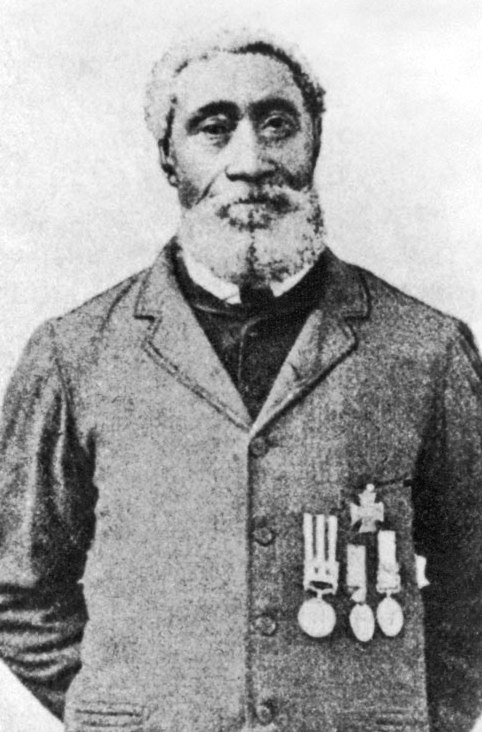

William Hall, VC. (DND Photo)

William Hall was the first Black person, the first Nova Scotian and one of the first Canadians to receive the British Empire’s highest award for bravery, the Victoria Cross. The son of former American slaves, Hall was born in 1827 at Horton, Nova Scotia, where he also attended school. He grew up during the age of wooden ships, when many boys dreamed of travelling the world in sailing vessels. As a young man, Hall worked in shipyards at Hantsport for several years, building wooden ships for the merchant marine. He then joined the crew of a trading vessel and, before he was eighteen, had visited most of the world’s important ports.

Perhaps a search for adventure caused young William Hall to leave a career in the American merchant navy and enlist in the Royal Navy in Liverpool, England, in 1852. His first service, as Able Seaman with HMS Rodney, included two years in the Crimean War. Hall was a member of the naval brigade that landed from the fleet to assist ground forces manning heavy gun batteries, and he received British and Turkish medals for his work during this campaign.

After the Crimean War, Hall was assigned to the receiving ship HMS Victory at Portsmouth, England. He then joined the crew of HMS Shannon as Captain of the Foretop. It was his service with Shannon that led to the Victoria Cross.

Shannon, under Captain William Peel, was escorting troops to China, in readiness for expected conflict there, when mutiny broke out among the sepoys in India. Lord Elgin, former Governor General of Upper Canada and then Envoy Extrodinary to China, was asked to send troops to India. The rebel sepoy army had taken Delhi and Cawnpore, and a small British garrison at Lucknow was under siege. Elgin diverted troops to Calcutta and, as the situation in India worsened, Admiral Seymour also dispatched Shannon, Pearl and Sanspareil from Hong Kong to Calcutta. Captain Peel, several officers, and about 400 seamen and marines including William Hall, travelled by barge and on foot from Calcutta to Cawnpore, dragging eight-inch guns and twenty-four-pound howitzers.

Progress was slow with fighting all along the way. At Cawnpore the Shannon crew joined another relief force under Sir Colin Campbell (later to become Lieutenant-Governor of Nova Scotia) and began the historic march to Lucknow.

The key to Lucknow was the Shah Najaf mosque, a walled structure itself enclosed by yet another wall. The outer wall was breached by the 93rd Highlanders at mid-day, and the Shannon brigade dragged its guns to within 400 yards (366 m) of the inner wall. William Hall volunteered to replace a missing man in the crew of a twentyfour- pounder. The walls were thick, and by late afternoon the 30,000 sepoy defenders had inflicted heavy casualties from their protected positions. The bombardment guns from Shannon were dragged still closer to the walls and a bayonet attack was ordered, but to little effect. Captain Peel ordered two guns to within 20 yards (18 m) of the wall. The enemy concentrated its fire on these gun crews until one was totally annihilated. Of the Shannon crew, only Hall and one officer, Lieutenant Thomas Young, were left standing.

Young was badly injured, but he and Hall continued working the gun, firing, reloading, and firing again until they finally triggered the charge that opened the walls. “I remember,” Hall is quoted as saying, “that after each round we ran our gun forward, until at last my gun’s crew were actually in danger of being hurt by splinters of brick and stone torn by the round shot from the walls we were bombarding.”

Captain Peel recommended William Hall and Thomas Young for the Victoria Cross, in recognition of their “gallant conduct at a twenty-four-pounder gun… at Lucknow on the 16th November 1857”.

Hall received his Victoria Cross aboard HMS Donegal in Queenstown Harbour, Ireland, on October 28, 1859. His naval career continued aboard many ships, among them Bellerophon, Hero, Impregnable, Petrel and Royal Adelaide, until he retired in 1876 as Quartermaster.

Hall moved back to Nova Scotia to live with his sisters, Rachel Robinson and Mary Hall, on a farm in Avonport overlooking the Minas Basin. A modest man, he lived and farmed without recognition until 1901, when HRH the Duke of Cornwall and York (later King George V) visited Nova Scotia. A parade of British veterans was held, and Hall wore his Victoria Cross and three other service medals. The Duke inquired about the medals and drew attention to Hall’s service.

William Hall was awared the Victoria Cross with blue ribbon, the Crimean War medal with Sebastopol and the Indian Mutiny medal with Lucknow clasp.

Three years later, William Hall died at home, of paralysis, and was buried without military honours in an unmarked grave. In 1937, a local campaign was launched to have Hall’s valour recognized by the Canadian Legion, but it was eight more years before his body was reburied in the grounds of the Hantsport Baptist Church. The monument erected there bears an enlarged replica of the Victoria Cross and a plaque that describes Hall’s courage and devotion to duty.

In 1967, William Hall’s medals were returned to Canada from England to be shown at Expo ‘67 in Montreal. As property of the Province of Nova Scotia, they were later transferred to the Nova Scotia Museum.

Subsequently, a branch of the Canadian Legion in Halifax was renamed in his honour. A gymnasium in Cornwallis, the DaCosta-Hall Educational Program for Black students in Montreal, and the annual gun run of the International Tattoo in Halifax also perpetuate his name.

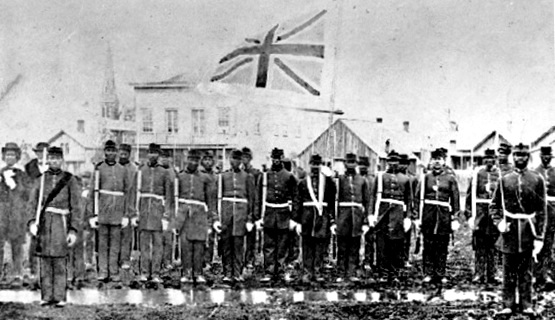

(BC Black History Awareness Society Photo)

Victoria Pioneer Rifle Corps, British Columbia, ca 1850s.

Black people in the West also forged their own military traditions. In the late 1850s, hundreds of black settlers moved from California to Vancouver Island in pursuit of a better life. Approximately 50 of the new immigrants soon organized the Victoria Pioneer Rifle Corps, an all-black volunteer force also known locally as the “African Rifles.” While the corps was disbanded by 1865 after only a few years of existence, it was the first officially authorized militia unit in the West Coast colony.

While relatively few black Canadians served in the military in the years immediately following Confederation, a few were part of the Canadian Contingent that went overseas during the South African War of 1899–1902. However, the First World War that erupted a decade and a half later would see a great change in how black Canadians served.

Like so many others swept up in the excitement and patriotism that the First World War (1914-1918) initially brought on, young black Canadians were eager to serve King and country. At the time, however, the prejudiced attitudes of many of the people in charge of military enlistment made it very difficult for these men to join the Canadian Army. Despite the barriers, some black Canadians did manage to join up during the opening years of the war. Black Canadians wanted the chance to do their part on a larger scale, however, and pressured the government to do so.

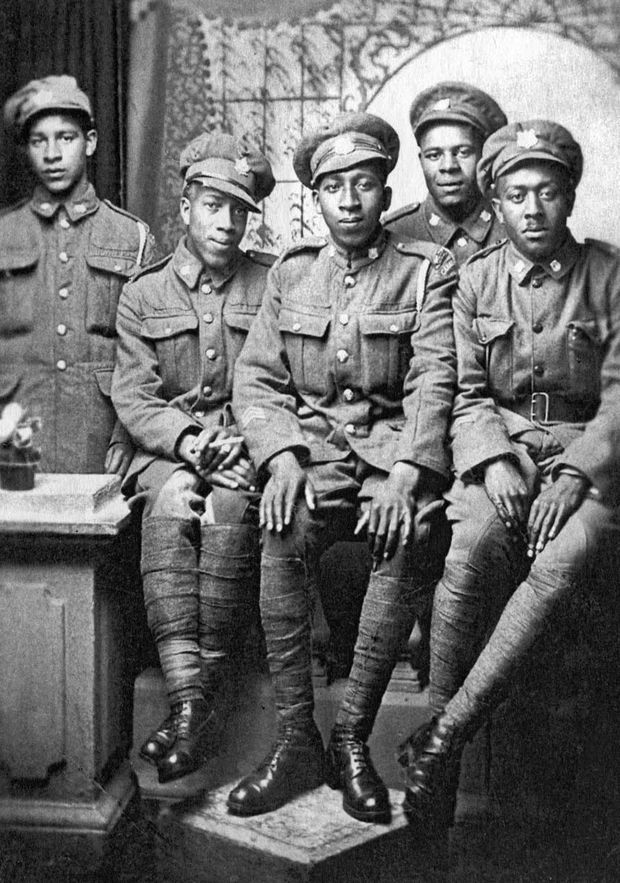

(Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia Photo)

No. 2 Construction Battalion, Nov 1916.

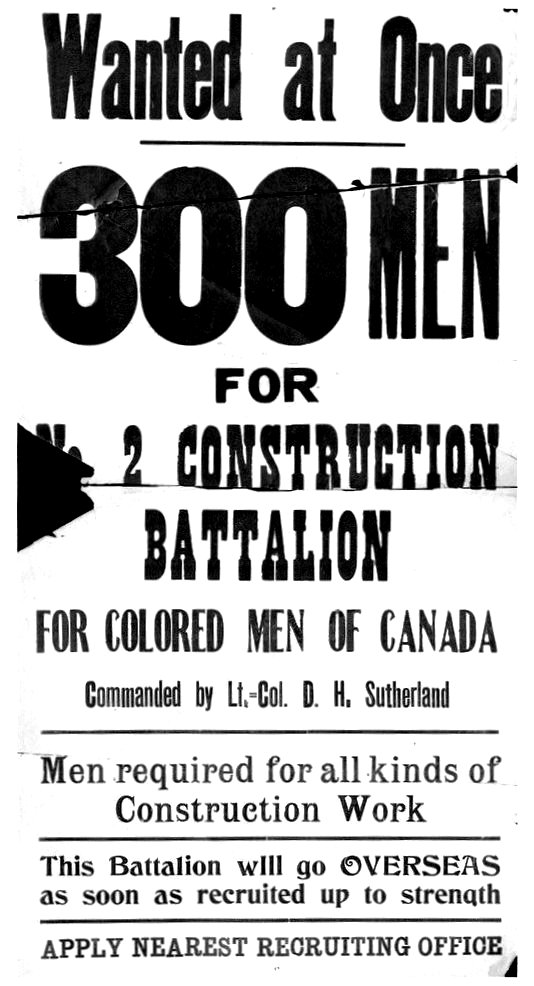

On 5 July 1916, the No. 2 Construction Battalion was formed in Pictou, Nova Scotia. It was the first large black military unit in Canadian history. Recruitment took place across the country. The No. 2 Construction Battalion was made up of 605 men who volunteered to serve in the Canadian military. Most of the men were black men from Nova Scotia, but others were from New Brunswick, Ontario and the Prairies. Some black men from the United States and the Caribbean came to join the battalion as well.

(Author Photo)

No. 2 Construction Battalion badge, Fredericton Region Museum.

No. 2 Construction Battalion recruiting poster.

The No. 2 Construction Battalion was formed specifically for black men to serve as part of the Canadian army. The No. 2 Construction Battalion helped to build trenches (the alleyways beneath the earth’s surface for hiding or launching attacks) for the soldiers at the front of the battle. Building and repairing roads, making small railways to move lumber and laying barbed wire were some of the jobs that the men in this special battalion were given to do.

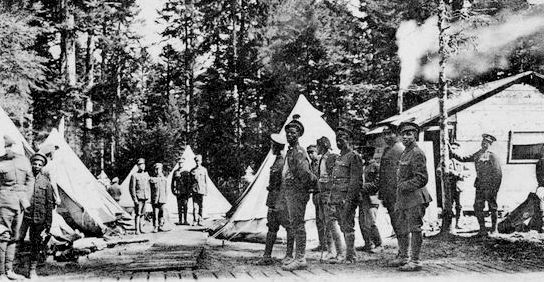

(The Army Museum, Halifax Citadel Photo)

No. 2 Construction Company camp, La Joux in France, 1917.

(The Army Museum, Halifax Citadel Photo)

No. 2 Construction Company camp, La Joux in France, 1917.

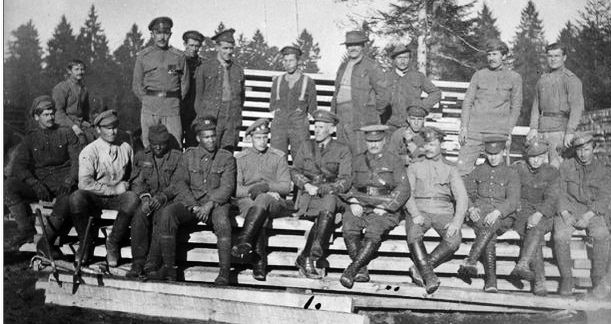

(Library and Archives Canada Photo)

No. 2 Construction Company, La Joux Camp, France, with Russian soldiers.

(The Army Museum, Halifax Citadel Photo)

No. 2 Construction Battalion band.

Back row Left To Right: Albert Carty, Elijah Tyler, George Dixon, Unknown.

Front row Left to Right: Herbie Nichols, Fred Dixon, George William Stewart, Seymour Tyler, Ralph Middleton. (Information courtesy of Jennifer Dow. George Stewart was her great great Uncle)

Seymour Tyler later served in the Second World War with the Carleton and York Regiment as their Bugle Sergeant. The Regiment Awarded him a Silver Bugle in 1939 for 21 years of service.

The No. 2 Construction Company Band was initially used to help recruit African Canadians at rallies and churches. Overseas, the band was highly regarded, even receiving an entry in the War Diary for Dominion Day 1918: “their excellent music, greatly assisted in entertaining the crowd and making the holiday a success.” (Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia)

(DND Photo)

No. 2 Construction Battalion members pose with ammunition before loading it into tramway cars to be taken up the line.

(Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia Photo)

Pte. Joseph Alexander Parris (center) and unidentified No. 2 Construction Battalion comrades, 1917.

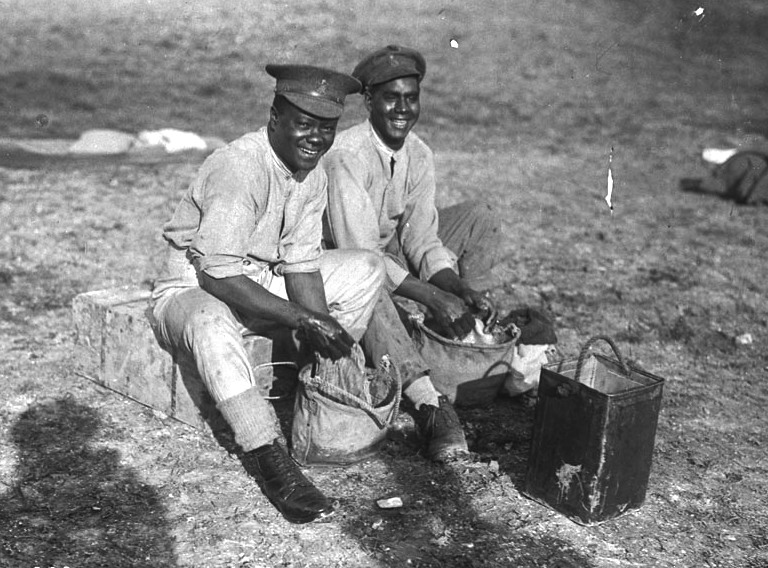

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3396685)

Black soldiers doing personal laundry, Sep 1916.

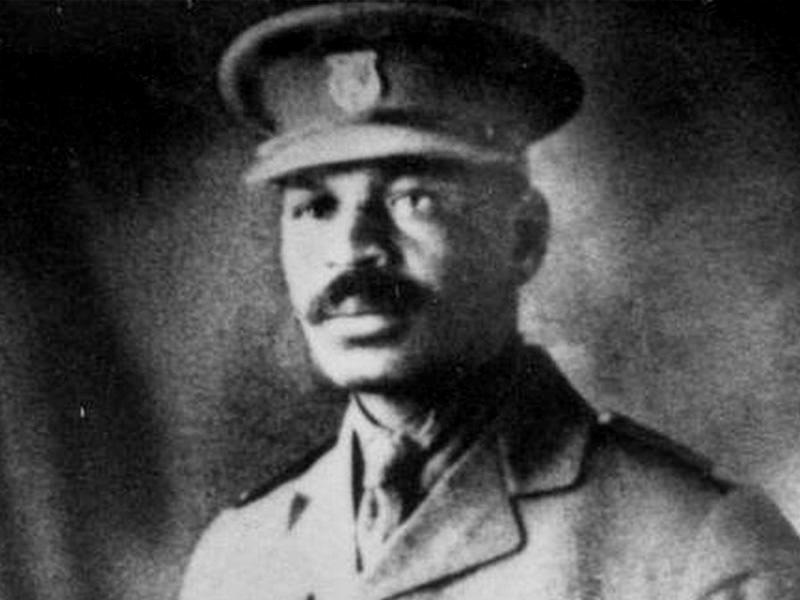

(Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia Photo)

Reverend William White. Born in Virginia in 1874, Reverend William White moved to Nova Scotia in 1899. During the First World War, in 1917, a year after the formation of No. 2 Construction Battalion in Pictou, Nova Scotia, Reverend White enlisted. He bacame the first commissioned officer of colour in the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF). In his role as Chaplain for the CEF’s only segregated unit, the battalion was tasked with non-combat support roles such as providing the lumber required to maintain trenches on the front lines, and helping construct roads and railways.

Also, Reverend White advocated for equality of Coloured soldiers both in Canada and overseas, preaching race consciousness and inspired advocacy and social advancement. For his service, Reverend White became Honourary Captain, one of the few commissioned officers of colour to serve in the Canadian Army during the First World War.

A few of the men from the battalion went on to serve as combat soldiers. Ethelbert (Curley) Christian and Seymour Tyler fought bravely in the battle for Vimy Ridge, one of Canada’s most famous military efforts. Tyler was awarded the British War Medal and the Victory Medal in the First World War, as well as the Canadian Volunteer Service Medal and the Defence Medal in the Second World War.

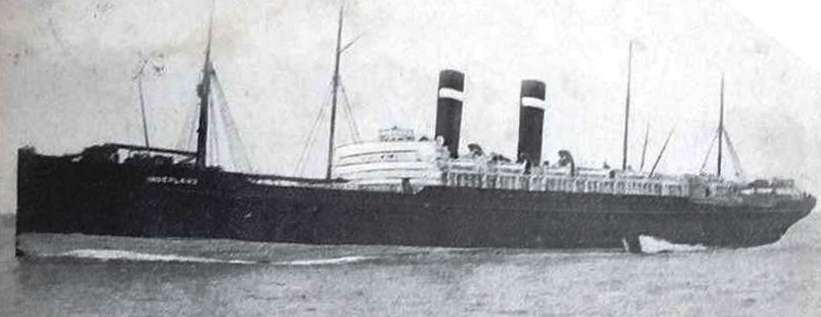

SS Southland (as the SS Vaderland), postcard.

The segregated battalion was tasked with non-combat support roles. After initial service in Canada, the battalion boarded the SS Southland bound for Liverpool, England in March 1917. This was a very dangerous journey. The ocean liner SS Southland (originally named the SS Vaderland), had been converted to a troopship, ferrying troops of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), including the No. 2 Construction Battalion, from Halifax to Liverpool, England. In September 1915, the SS Southland had been torpedoed in the Aegean Sea by the German submarine UB-14 with the loss of 40 men. The ship was beached, repaired, and returned to service in August 1916. While in service between the United Kingdom and Canada on 4 June 1917, the SS Southland was torpedoed a second time, this time by U-70. She sank off the coast of Ireland with the loss of four lives.

The soldiers of No. 2 Construction Battalion were sent to eastern France later in 1917 where they served honourably with the Canadian Forestry Corps. There they helped provide the lumber required to maintain trenches on the front lines, as well as helped construct roads and railways. After the end of the First World War in November 1918, the men sailed to Halifax in early 1919 to return to civilian life and the unit was officially disbanded in 1920.

In addition to the men of the Black Battalion, an estimated 2,000 black Canadians, such as James Grant, Roy Fells, Seymour Tyler, Jeremiah Jones and Curly Christian, were determined to get to the front lines and managed to join regular units, going on to give distinguished service that earned some of them medals for bravery.

Jeremiah Jones of Truro, Nova Scotia, was recommended for the Distinguished Conduct Medal for capturing a German machine post at Vimy Ridge in 1917. (Jones family Photo)

Black Canadians also made important contributions on the home front. They helped achieve victory by working in factories making the weapons and supplies needed by the soldiers fighting overseas, and by taking part in patriotic activities like raising funds for the war effort.

Today, the dedicated service of the “Black Battalion” and other black Canadians who fought in the First World War is remembered and celebrated as a cornerstone of the proud tradition of Black military service in our country.

Little more than 20 years after the end of the “War to End all Wars,” the Second World War (1939–1945) erupted and soon spread across Europe and around the globe. The Second World War saw considerable growth in how black Canadians served in the military. While some black recruits would encounter resistance when trying to enlist in the army, in contrast to the First World War no segregated battalions were created. Indeed, several thousand black men and women served during the bloodiest war the world has ever seen. Black Canadians joined regular units and served alongside their white fellow soldiers here at home, in England, and on the battlefields of Europe. Together they shared the same harsh experiences of war while fighting in places like Italy, France, Belgium and the Netherlands.

In the early days of the Second World War, black volunteers to the armed forces were initially refused, but starting in 1940, the Canadian Army agreed to take black volunteers, and by 1942 were willing to give blacks officers’ commissions. Unlike in the First World War, there were no segregated units in the Army and black Canadian always served in integrated units. The Army was more open to black Canadians rather than the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) and the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), which both refused for some time to accept black volunteers. By 1942, the RCN had accepted black Canadian as sailors while the RCAF had accepted blacks as ground crews and later as airmen, which meant giving them an officer’s commission as in the RCAF airmen were usually officers. In 1942, newspapers gave national coverage when the five Carty brothers of Saint John, New Brunswick all enlisted in the RCAF on the same day with the general subtext being that Canada was more tolerant than the United States in allowing the black Carty brothers to serve in the RCAF.

(IWM Photo, CH 11320)

Handley Page Halifax, Boulton-Paul 4-gun tail turret.

The youngest of the Carty brothers, Gerald Carty, served as a tail gunner on a Halifax bomber, flying 35 missions to bomb Germany and was wounded in action.

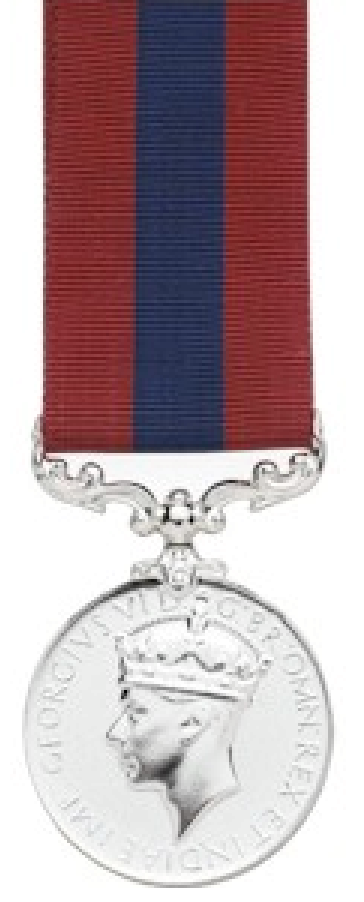

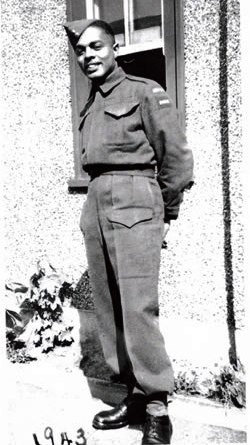

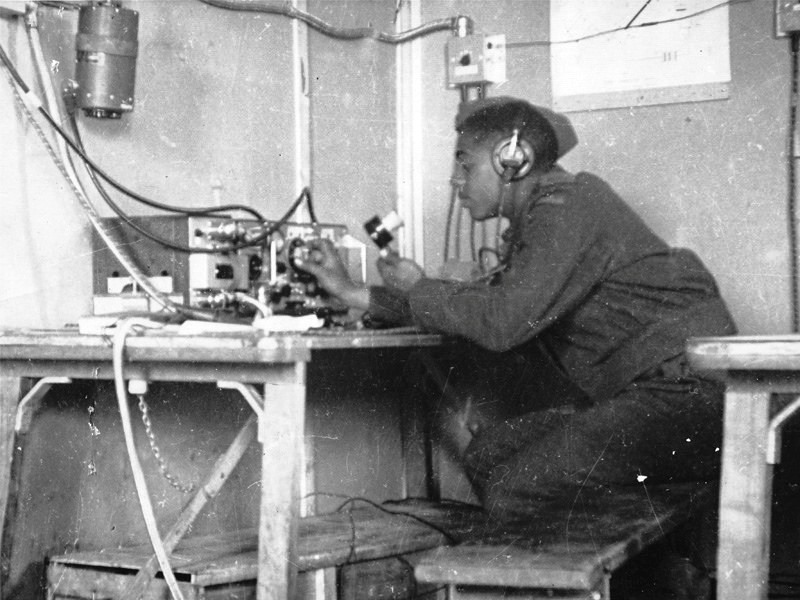

Welsford Daniels in 1943. (Daniels Family Photo). Aircrew Over Europe medal.

(Daniels Family Photo)

Welsford Daniels, born in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 1920, joined the Reserve Army in 1939 and served with the Royal Canadian Corps of Signals during the Second World War. He was tasked as a signalman where his responsibilities were repairing every type of electronic equipment for every communication platform and staying close behind the front lines to report casualties.

When a communication line broke down, he traveled at night through areas that were not cleared out. Daniels put his life in jeopardy and successfully fixed the communication line. He also went to Red Cross units to ensure that the wounded received proper care.

In the early years of the war, however, the Royal Canadian Navy and Royal Canadian Air Force were not as inclusive in their policies. This did not mean that trail-blazing black Canadians did not find a way to persevere and serve. Some black sailors served in the Navy, and black airmen served in the Air Force as ground crew and aircrew here at home and overseas in Europe.

The contributions of black servicemen were second to none and several earned decorations for their bravery. Some black women joined the military as well, serving in support roles so that more men were available for the front lines.

(DND Photo)

Robert Milton Cato (3 June 1915 – 10 February 1997) was born in Saint Vincent, British Windward Islands. He attended the St. Vincent Boys Grammar School from 1928 to 1933. On leaving school, the young Cato was articled to a Barrister-at-law in Kingstown, and began his career in law and was called to the Bar, Middle Temple in 1948. In 1945, he joined the First Canadian Army, attained the rank of Sergeant and gave active service in the Second World War in France, Belgium, Holland and Germany. Robert Milton Cato was married to Lucy Alexandra. He became a Saint Vincentian politician who served as the first Prime Minister of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and also held the offices of Premier of Saint Vincent and Chief Minister of Saint Vincent before independence. Cato was the leader of the Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Labour Party, and led the country through independence in 1979.

He was awarded the Canadian Volunteer Service Medal and Clasp; the France and Germany Star,the Defense Medal, and the War Medal.

warded the Canadian Volunteer Service Medal and Clasp; the France and Germany Star,

the Defense Medal, and the War Medal.”

(Library and Archives Canada Photo)

Cecilia Butler working in the John Inglis Company munitions plant in Toronto during the Second World War, December 1943. The mobilization of the Canadian economy for “total war” gave increased economic opportunities for both black men and even more so for black women, many of whom for the first time in their lives found well-paying jobs in war industries.

On the home front, black Canadians again made important contributions by working in factories that produced vehicles, weapons, ammunition and other materials for the war effort, and taking part in other patriotic efforts like war bond drives. For example, black women in Nova Scotia worked in vital jobs in the shipbuilding industry, filling the shoes of the men who would usually do that work but who were away fighting in the war. Many black Veterans returned home after the war with a heightened awareness of the value of freedom and their right to be treated as equals after all they had done for Canada in their country’s time of need. The service of black Canadians in the Second World War remains a point of pride and was a measure of how black Canadians were becoming increasingly integrated into wider Canadian society.

Since the end of the Second World War, the tradition of black Canadian service in the military has expanded and evolved.

In the Korean War (1950–1953), Canadians returned to the battlefield scarcely five years after the end of the Second World War, travelling halfway around the world to join the United Nations forces fighting to restore peace in Korea. Black soldiers were among the Canadian Army troops that were sent to fight so far from home.

While some last traces of discrimination continued in Canadian military recruiting practices into the mid-1950s, Black Canadians became more established in the Royal Canadian Navy and Royal Canadian Air Force, as well. For example, Raymond Lawrence joined the Navy in 1953, rising to become the first black Petty Officer 1st class and first black coxswain on a Canadian ship.

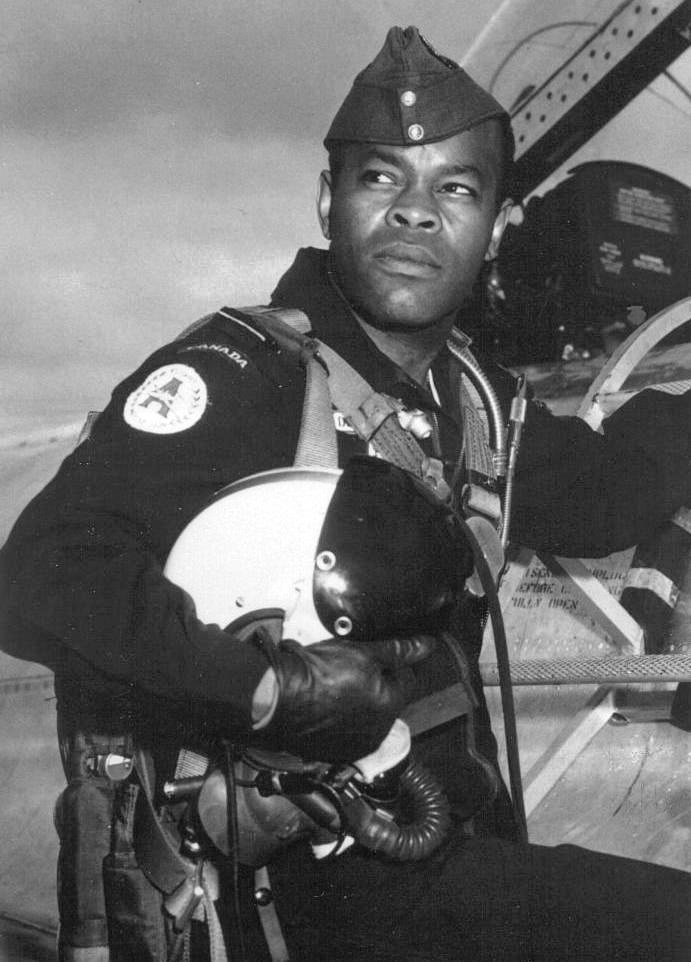

(DND Photo)

Major Stephen Blizzard, shown boarding a Canadair CT-133 Silver Star jet trainer.

The RCAF’s Major Stephen Blizzard was a flight surgeon and got his wings in the 1960s as a jet pilot during a long and varied career in the Canadian military. Born in Trinidad in 1928, Major Stephen Blizzard was a Canadian military trailblazer both in the air and in medicine, and is one of the National icons of Trinidad and Tobago. He practiced medicine in Trinidad before moving to Canada in 1958 where he studied medicine at Western University. To pay for his studies, he joined the Air Force Reserve Officer Training Program, and worked at the National Defence Medical Centre (NDMC) in Ottawa. After years of hard work, Blizzard became a Base and flight surgeon and a jet pilot in the 1960s. In 1978, he was the first doctor on site in “Operation Magnet,” being the first airlift to bring 604 Vietnamese refugees to Canada. Major Blizzard made imperative contributions to aviation medicine in Canada, and internationally, in both military and civil fields. His most prominent work was on the effects of pilot fatigue, jet lag, and proper in-flight care.

(DND Photo via James Craik)

Canadair CT-133 Silver Star, RCAF (Serial No. 21168).

(Canadian Forces Photo)

Major Walter Peters was Canada’s first black jet fighter pilot and an air force flying instructor. He helped in the development of the Snowbirds and counted the two years he later spent flying with the military’s aerobatic team as the highlight of his long aviation career. Born in Litchfield, Nova Scotia in 1937, he enrolled in the RCAF in 1961 at the age of 24, and entered pilot training

Born in Litchfield, N.S., in 1937, Mr. Peters was the youngest of six children. His family moved to Saint John when he was young. He was a gifted athlete and won a scholarship to Mount Allison University, where he completed an engineering degree. While studying at Mount Allison, he met and married Nancy, a white woman from Sackville, New Brunswick.

Walter Peters had a distinguished aviation career that included becoming the Canadian Armed Forces’ first human rights officer, as well as an adviser to the United Nations Security Council, offering advice on the tactical movement of troops by air. While in that position, he analyzed and briefed the council after the Soviet military shot down a Korean civilian jet in 1983.

After he retired from the Canadian Forces as a major, and later played a role in the establishment of the Canadian Aviation Safety Board, which investigated Air India Flight 182 that was brought down in the Atlantic Ocean in June 1985, by a Sikh terrorist bomb. He worked with Transport Canada, where he was responsible for creating and implementing safety programs for aviation. Walter Peters died on 24 Feb 2013 in Ottawa after suffering a stroke. He was 76.

(Canadian Forces Photo)

LCol Shelley Peters Carey, OMM, CD, enrolled in the RCMP in 1982. She was the first Black Canadian to join the RCMP. Peters Carey, who’s from Saint John, New Brunswick, was one of just 20 Canadian women in her group at basic training. She began her RCMP career working in Newfoundland and Labrador, where she was the only female Mountie at her detachments. Peters Carey stayed with the Mounties until 1986 and then went to work for the Canadian Forces (CF). In 2006, she was named the director of human rights and diversity. She held that position and also served as the deputy chair for NATO’s committee on women. When she retired as a Lieutenant-Colonel in 2012, she was the highest-ranking black woman in the Canadian Forces.

LCol (Retired) Shelley Carey began her military career by initially enrolling in the Canadian Forces Air Reserve Augmentation Flight at 8 Wing Trenton, Ontario, in 1980 and then later as a Direct Entry Officer. In the intervening period, she was enrolled in the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), becoming the first black female member of the RCMP, with postings to Happy Valley-Goose Bay, Labrador and Ferryland, Newfoundland.

In 1986 LCol Carey enrolled in the CF as a Direct Entry Officer. After she completed Basic Officer Training and the Basic Military Police Officer Training Course, she was posted to 5 Military Police Platoon at CFB Valcartier, Quebec as the Deputy Commanding Officer, the first woman and black to hold that position.

At CFB Valcartier, LCol Carey’s initial employment included assignments as the Security Advisor at the Canadian Forces Data Centre in Ottawa, Ontario, and as the Wing Security and Military Police Officer at 14 Wing Greenwood, Nova Scotia.

She was promoted to Major in 1996, and transferred to National Defence Headquarters (NDHQ) where she became the Project Director for the Security and Military Police Information System, then the Deputy Provost Marshal for Resource Management, the Deputy Provost Marshal for Policing and the Deputy Provost Marshal for Professional Standards (the Internal Affairs Branch of the Military Police).

From April to October 2002, LCol Carey served as the Provost Marshal and Chief Force Protection Officer for the multinational NATO mission in Bosnia-Herzegovina. In 2003 she was featured as one of the outstanding women in leadership roles by Rotman School of Business. In 2006, Lieutenant-Colonel Carey was named as the Director of Human Rights and Diversity, a position she held until her retirement from the Canadian Forces in December 2008.

From June 2006-December 2008, Lieutenant-Colonel Carey also served as the Deputy Chair for the Committee of Women in the NATO Forces. At the time of her retirement, she was the senior ranking black female in the Canadian Forces. LCol (Retired) Carey recently left an executive position in the Federal Public Service and now works for the Royal Canadian Legion as a Veterans Advocate.

In 2006, Lieutenant-Colonel Carey was featured in Who’s Who in Black Canada 2 and in Januaury 2009, she was inducted as an Officer of the Order of Military Merit. She is a graduate of the Law and Security Administration Program from Loyalist College as well as the Advanced Human Resources Professional Program from the Rotman School of Business. (Canadian Forces)

Canadian War Nurses

It is important to mention the Canadian war nurses, especially those of Colour. Although there are no records of specific nurses, they are just as crucial as those who served on the front line. While the front line protected our country, the nurses protected them. And we cannot forget the Canadian women who served in other areas during war such as factory workers who helped manufacture war equipment.

Over the decades since the Korean War, black Canadians have gone on to serve in every branch of the military, in duties both here at home and in operations around the world during the Cold War and in international peace support efforts (right from the first large-scale United Nations peacekeeping mission to Egypt during the Suez Crisis of the 1950s).

(DND Photo)

Ordinary Seaman Lisa Nelson relays information from the bridge during drills aboard HMCS Regina patrolling the Gulf of Oman in 2003.

(Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Bryan Reckard, USN Photo)

HMCS Regina (FFH 334), 23 June 2008.

Today, black Canadians standing on the shoulders of the trailblazers who led the way continue to serve proudly in uniform where they share in the sacrifices and achievements being made by the Canadian Forces. Our country’s efforts in Afghanistan have come at a high cost, one that has been borne by black soldiers, as well. Brave men like Ainsworth Dyer and Mark Graham are among the more than 150 Canadian Forces members who have died in Afghanistan since 2002.

Corporal Ainsworth Dyer 1977 – 2002, Soldier, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI),

Killed in Afghanistan. (DND Photo)

Corporal Dyer, the son of the late Paul and Agatha Dyer, was born in Montréal, Quebec. He grew up in Regent Park, a downtown neighbourhood in Toronto. Raised by his strict Jamaican grandmother, he had a strong sense of right and wrong.

In February 1996, Ainsworth Dyer enrolled with the Militias 48th Highlanders of Canada as an infantryman. In October 1997, he transferred to the Regular Force. When completing battle-school he became a member of the Edmonton-based battalion of the PPCLI. After joining the 5 Platoon in 1998, he quickly developed into a mature and responsible soldier. He served as a Rifleman and was deployed on Operation Palladium to Bosnia-Herzegovina in 2000.

Always looking to challenge himself, Ainsworth trained for the “Mountain Man” competition, the blood and guts of the light infantry soldier. He also conquered the skies and became a paratrooper. His sense of adventure complemented his strong temperament.

Corporal Dyer was one of four Canadians killed during a “friendly fire” incident in Afghanistan in 2002. Eight other soldiers from the Battalion were injured. This tragedy is referred to as The Tarnak Farm Incident. An American F-16 fighter jet piloted by an Air National Guard dropped a laser-guided bomb on the Canadians who were conducting a night firing exercise at Tarnak Farms. The deaths of these Canadian soldiers were Canada’s first during the war in Afghanistan and the first in a combat zone since the Korean War.

Corporal Ainsworth Dyer was buried with full military honours in the Necropolis Cemetery in Cabbagetown. In a touching moment, his parents released a box of doves.

In February 2003, Corporal Dyer was commemorated on the Rakkasan Memorial Wall at Fort Campbell, Kentucky.

The Ainsworth Dyer Bridge, a footbridge in Edmonton’s Rundle Park , has special meaning for both the Dyer and Von Sloten families. It was at this spot that Ainsworth proposed to his girlfriend Jocelyn Von Sloten before he left for Afghanistan. After Ainsworth was killed, Aart Von Sloten, Jocelyn’s father, began making wooden crosses for all the soldiers killed in Afghanistan. Each cross is inscribed with the name and rank of the 158 men and women who died while serving in the Canadian forces in Afghanistan. Over the years, a ceremony has been held on Remembrance Day and the names of those who have died are read aloud and a cross placed in the ground in their honour. The ceremony began with a small group but has grown to include many people who wish to pay their respects to these fallen soldiers.

Ainsworth Dyer is described by his colleagues as a thoughtful leader, his own man, and one who had strength of heart that was unparalleled. He will be remembered as a brave soldier. In the words of retired Sgt. Oswald Reece, who trained Ainsworth as a young recruit, “he was a standout person; he was always ready to step up to the plate; he was the perfect soldier.”

Mark Anthony Graham (17 May 1973 in Gordon Town, Jamaica, killed 4 September 2006 in Panjwaii, Afghanistan. He was a Canadian Olympic athlete and soldier who died while participating in Operation Medusa during the NATO mission in Afghanistan. Graham grew up in Hamilton, Ontairo, lived in Calgary, Alberta and had been stationed at CFB Petawawa, Ontario. He attended Chedoke Middle School and then Sir Allan MacNab Secondary School in Hamilton, then the University of Nebraska and later Kent State in Ohio, on track-and-field scholarships. (RCR Photo)

On 4 September 2006 Graham was killed in a friendly fire incident when two USAF A-10 Thunderbolts fired on his platoon, having mistaken them for Taliban insurgents.

Source: Veteran’s Affairs Canada. https://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/those-who-served/black-canadians-in-uniform/history