Kite Balloons over Canadian soldiers in France, First World War

Barrage balloons are attached to cables fixed to the ground or vehicles for observation and to provide an obstacle to attacking aircraft. Kite balloons have a “bomb-like” appearance that reduces drag and are more stable in high winds. During the First World War, the armies of England, France, Germany and Italy made extensive use of barrage balloons. In some cases, such as in the defence of London, steel cables were hung from several balloons connected to form a “barrage net” that could be raised as high as (4.5 km or roughly 15,000 ft), effective against the bombers of the era.

These balloons were primarily employed as an aerial platform for intelligence gathering and artillery spotting. The First World War kite balloons were fabric envelopes filled with hydrogen gas. Unfortunately, the flammability of the gas led to the destruction of hundreds of balloons on both sides. Observers manning these observation balloons frequently had to use a parachute to escape when their balloons were attacked. To avoid the potentially flammable consequences of hydrogen, observation balloons after the First World War were often filled with non-flammable helium. As will be seen in the following photos, balloons were usually tethered to a steel cable attached to a winch that reeled the gasbag to its desired height (usually 1,000-1,500 metres) and retrieved it at the end of an observation session.

Canadian soldiers would often see Kite balloons in use for observation over their sector of the Western front. A number of these balloons were photographed for the record, with a few of them presented here from the Library and Archives Canada files.

“The balloon’s going up!” was an expression for impending battle. It is derived from the fact that an observation balloon’s ascent likely signaled a preparatory bombardment for an offensive.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3395330)

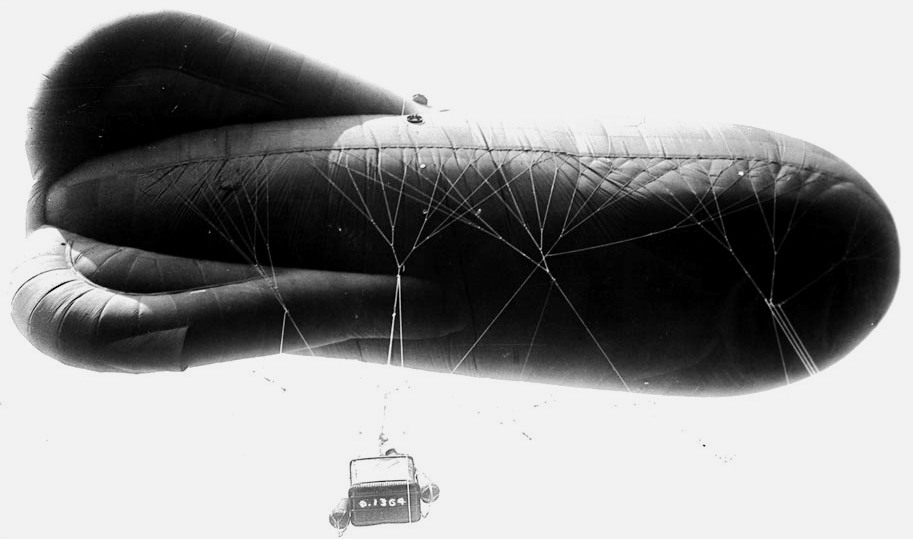

Kite balloon behind Canadian lines at Vimy Ridge, France, Dec 1917.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3395204)

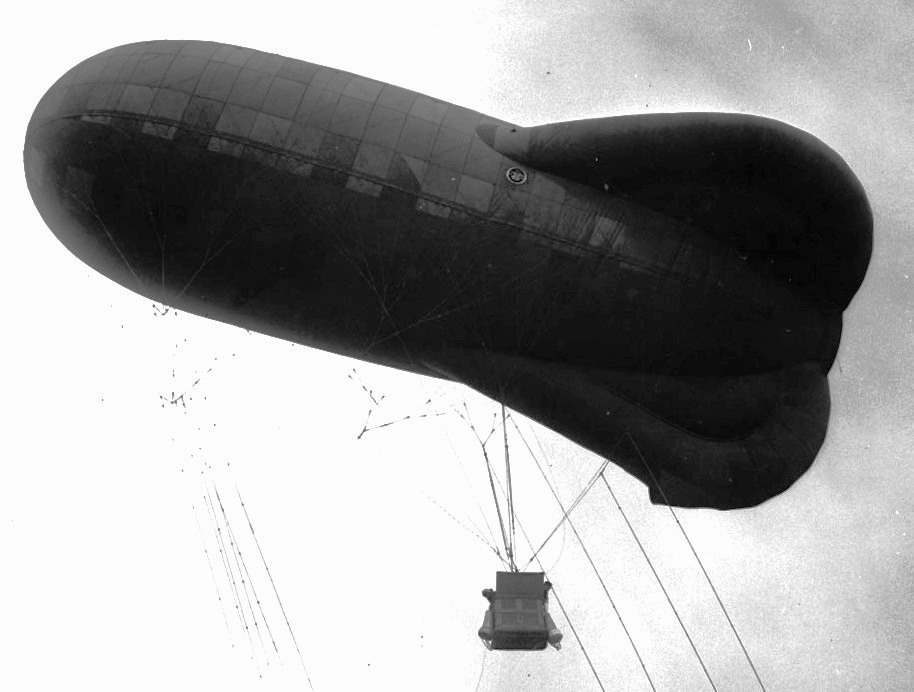

Kite Balloon over the Western Front, Oct 1916.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3405554)

Kite balloon being prepared for launch with a Canadian Kinematographer on board, May 1917.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3405555)

Kite balloon with Canadian Kinematographer and Observer, May 1917.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3395244)

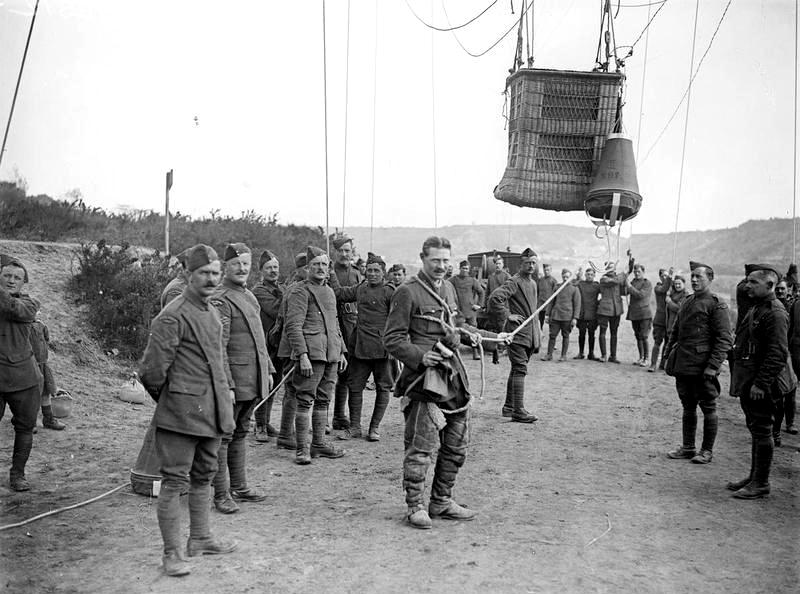

Kite Balloon operators donning parachutes and checking cameras before ascending, May 1917.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3395176)

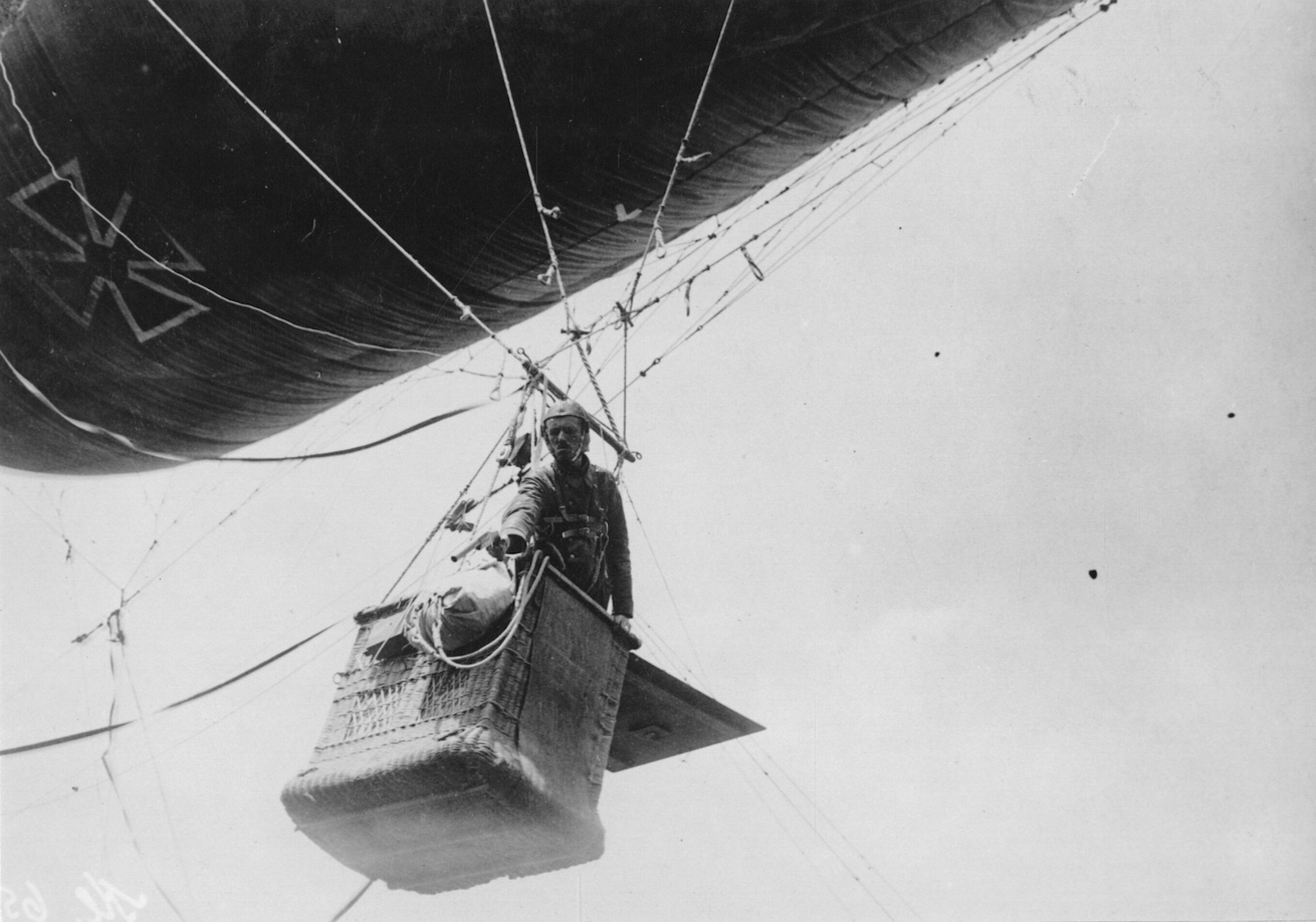

Kite balloon pilot and observer, Sep 1916.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3395184)

Kite balloon observer testing his telephone before ascending, Sep 1916.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3395241)

Kite Balloon in operation over the Western Front, France, May 1917.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3521909)

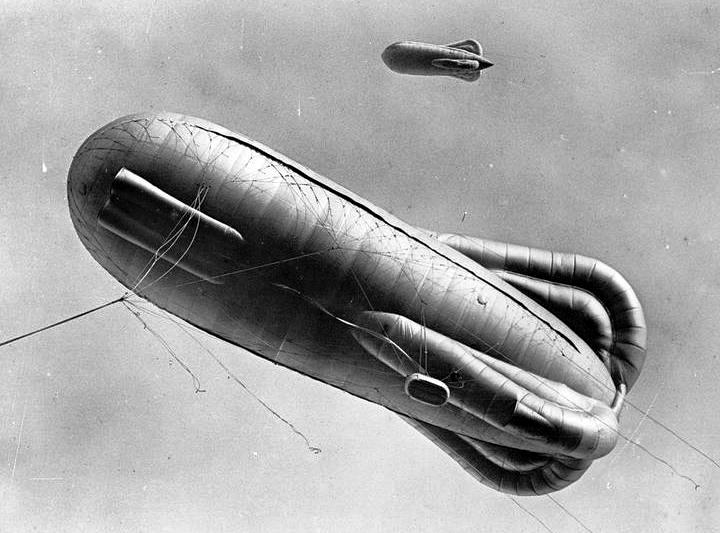

Kite balloon pair over Canadian lines, Apr 1917.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3395253)

Kite balloon windlas and crew, fixing the 500′ flag to a cable, May 1917.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3404749)

Kite balloon view of the windlass and crew at work on ascent, Oct 1916.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3404754)

Kite balloon view of the windlass and crew at work on ascent, Oct 1916.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3522065)

Kite balloon view of the trench lines around Arras, Nov 1917.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3395177)

Kite Balloon in operation over the Western Front, France, Sep 1916.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3395332)

Kite balloon being moved to a launch site, Dec 1917.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3395174)

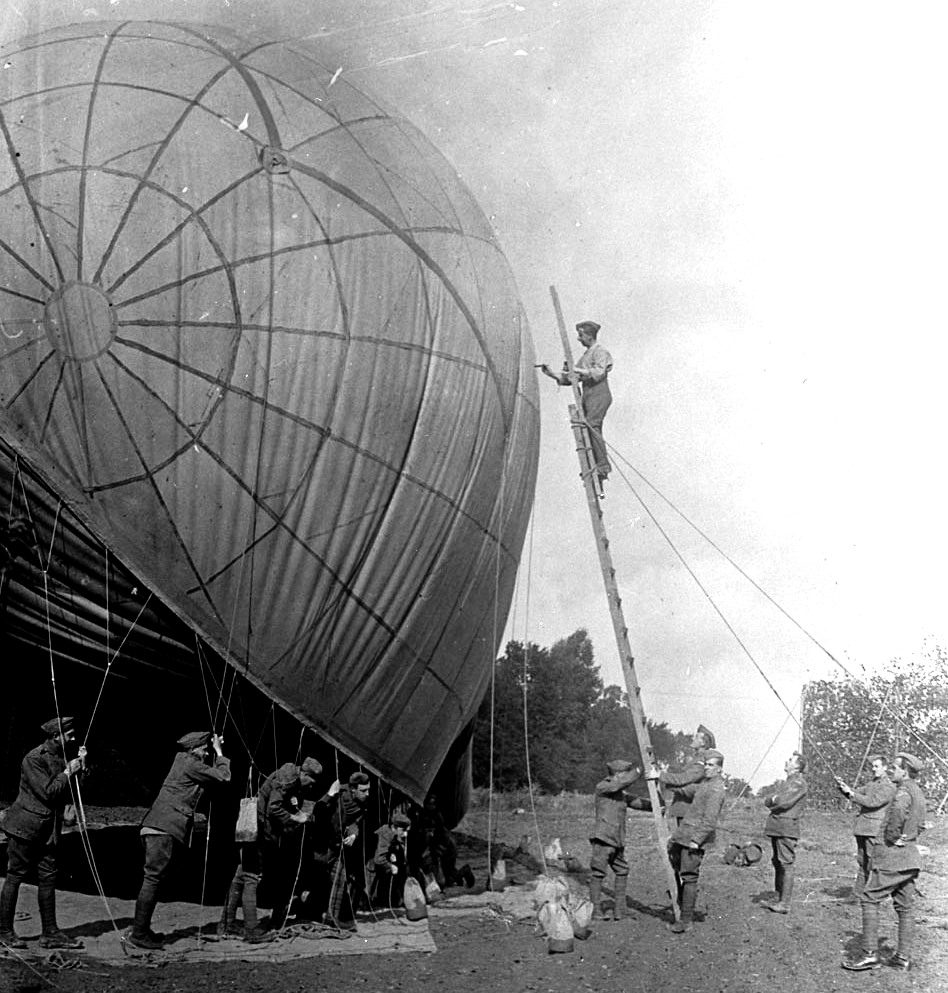

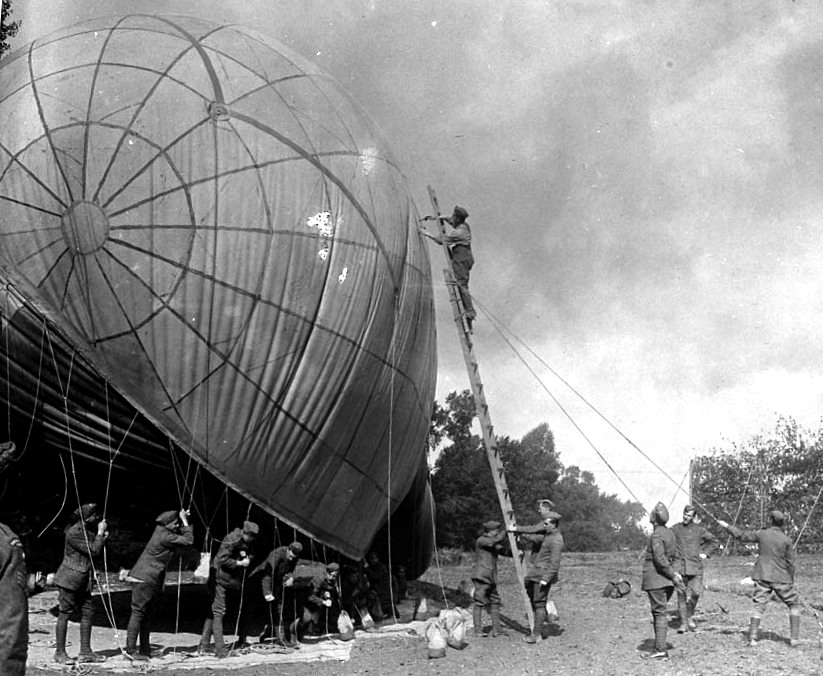

Kite balloon being brought out for launch, Sep 1916.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3395251)

Kite balloon gas bag feing filled, May 1917.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3194241)

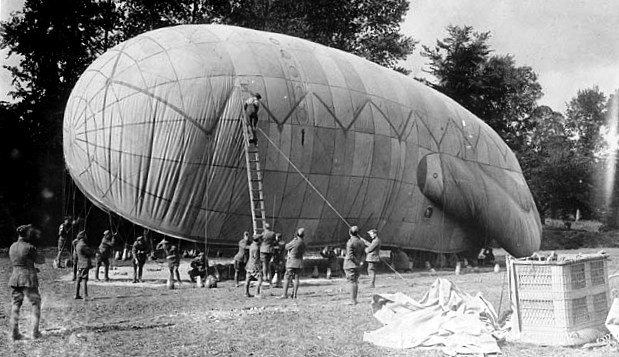

Kite balloon being overhauled on the Western Front, France, Oct 1916.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3395194)

Kite balloon being repaired prior to ascent, Oct 1916.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3395197)

Kite balloon being repaired prior to ascent, Oct 1916.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3395196)

Kite balloon landing behind Canadian lines, Oct 1916.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3395207)

Kite balloon being launched on the Western Front, Oct 1916.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3404934)

Kite balloon being lowered as Canadian Artillery moves by, East of Arras, Sep 1918.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3404935)

Kite balloon being lowered as Canadian Artillery moves by, East of Arras, Sep 1918.

(IWM Photo, Q11901)

A Caquot kite balloon ready to ascend, near Metz, France on 25 Jan 1918. A motor winch and infantrymen are hauling on ropes to hold the balloon down.

(IWM Photo, Q27466)

Two Caquot Kite Balloons in the air, seen from underneath.

(Australian War Memorial Photo, E01254)

An observation balloon ready to ascend over Ypres, France, 31 Oct 1917.

(IWM Photo, Q11892)

A Caquot kite balloon with the basket at ground level. In the foreground a field kitchen can be seen, and behind it an RE cable cart, behind which can be seen the men hauling on the ropes to keep the balloon down. Near Ypres, France, 5 October 1917, during the Battle of Passchendaele, July-Nov 1917.

(IWM Photo, Q11893)

A Caquot kite balloon after being hauled down by its winch. Air mechanics are hauling on ropes to keep the basket on the ground. Near Ypres, France, 5 October 1917.

(IWM Photo, Q12026)

The basket of a kite balloon, showing the observer’s parachute attached to it, and the parachute harness attached to the officer. Photograph taken on 2 May 1918, Gosnay, France.

(IWM Photo, Q12027)

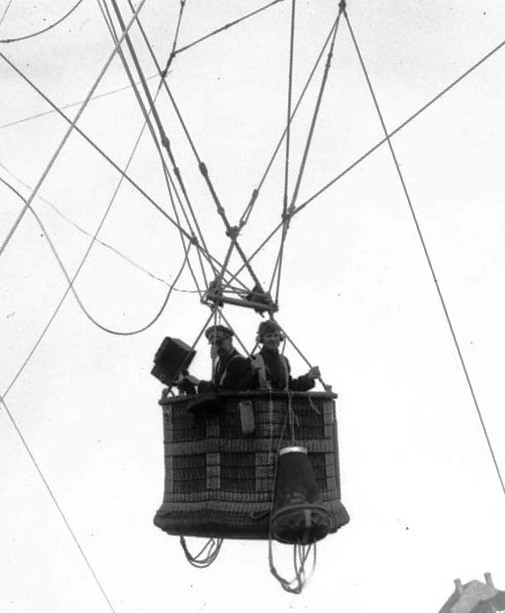

Two observer officers in the basket of a kite balloon. Note the telephones, map rest, parachute and parachute harness. Photograph taken in Gosnay, 2 May 1918

(IWM Photo, Q11909)

A British Caquot kite balloon falling down in flames after having been attacked by an enemy aircraft. Boyelles, France, 3 February 1918.

…and on the other side:

(Christoph Herrmann Photo)

German Parseval-Siegsfeld type balloon at Équancourt, France, in September 1916. The rear “tail” fills with air automatically through an opening facing the wind.

(US National Archives Photo)

Austro-Hungarian Drachenballon in 1917.

The Parseval-Sigsfeld Drachenballon was a German observation balloon designed to replace the older spherical-type balloons used for nearly a century. The balloon would be designed in such a way that it would face into the wind, and be much more stable over its predecessor, using design attributes similar to kites. The Drachenballon would be used in several wars over its lifetime, including widespread use during the First World War. Here, it saw service on almost all fronts, and would even be copied by the Allies. The type would eventually be replaced by the much more stable Caquot/Type Ae 800 observation balloons in 1916, but despite this would continue to see service until the 1920s.

The Drachenballon was a captive observation balloon developed for the German Empire. The main body consisted of a large cylinder shape made out of rubberized fabric that was filled with hydrogen gas. Gas pressure and release was regulated by a valve in the nose of the balloon. It could do so automatically, or manually via rope. At the rear of the body was an internal air bag, or ballonet, that was filled with air via the wind to keep the balloon’s shape if the hydrogen gas bag was not fully filled yet. Underneath the ballonet was an air inlet that was fed directly by the wind. On the underside of the front of the balloon was its neck, where the hydrogen gas would be pumped into the gas bag while it was on the ground. Two valves placed on each side of the gas bag/ballonet could be opened to quickly release the gas/air and descend. On each side of the balloon’s body was a small stabilizing fin. Early examples of these were triangular in shape, but they became rectangular near the outbreak of World War I. At the back of the body was a steering bag that was sewn on. The steering bag was made of regular fabric and was designed to keep the balloon stable and facing into the wind. The steering bag was inflated by wind via a large intake at the bottom of the bag facing forward, and a smaller intake located on the bag itself. At the top of the steering bag was a safety valve that permitted excess air to escape. The steering bag was held together via rigging to the main body. Connected to the steering bag was the tail of the balloon, which was a long cable with up to 6 removable tail cups, resembling small parachutes which trailed behind the main balloon, that helped with stabilization. The balloon would face towards the wind at an angle of 30-40 degrees. Slightly below the equator of the balloon was the balloon girdle. This was made of rubber and served as the attachment point for all of the balloon’s rigging. Various ropes were used for the rigging, which kept the different parts of the balloon together. Three colors of rope were used to differentiate their specific sections; white, red and blue. Blue rope was rigging for the steering bag, white rope was for cable rigging and red ropes connected to the observer’s basket. It is unknown if rope colors were used throughout its service or if the copies used by the Allies also used colored ropes. The cable that connected the balloon to the ground and the ropes that connected the basket were different ropes and were not connected together. On the ground, the steel mooring line was connected to a pulley that prevented the balloon from moving and could lower or raise the balloon at will.

(US National Archives Photo)

A balloon operator fires a signal gun in the basket of a German Drachenballon.

The basket of the Drachenballon was made of willow and bamboo and was secured to the balloon by four ropes. These ropes were adjustable by the crew to prevent the basket from swinging around. Accommodations for the observer were located in the basket. A telephone could be placed in the basket and would have its cable connected to the ground via an internal wire that went through the mooring cable. Two pockets were located inside the basket to store equipment, as well as ten metal cases to protect valuable reports. Once a report was finished, it was put into a case and dropped from the balloon to the ground. Flags were put on the cases to help the ground crew find them more easily. Standard operating height for captive observation balloons were 500m, but if the weather was rough, the balloon would be raised to 300m instead. The larger Drachenballon variants created during the First World War would be able to achieve a maximum height of 2,000 meters. Inflation of the balloon would take 15 minutes, with ascension taking 10 minutes and descent taking 5 minutes. Equipment used by the observer included maps, notebooks, two signal flags (one red, one white), a barometer, a knife, two looking glasses of varying magnification, and a signal disk to show what commands could be done with the flags. Later on during the First World War, parachutes would also become standard onboard equipment. Additional equipment that could be carried included signal flares, a flare gun, or a camera. On Drachenballons used by the Navy or aboard ships, life preservers were standard issue. A single observer would remain in the basket during operations but up to 48 men made up the ground crew that would handle moving, inflating, deflating, and transporting the balloon and its associated equipment.

(Australian War Memorial Photo collection, H13497)

A German observation balloon fitted with a long distance camera about to ascend with one observer in the basket. The observer’s escape parachute can be seen attached to the outside of the basket.

The Drachenballon would be used for observation of enemy troop positions and movements, and would report on the current situation of the battle. Gun sighting and fire correction were also reported during battle to adjust the accuracy of artillery used near the balloon. Aboard ships, the Drachenballon was used for rangefinding purposes. During the First World War, submarine spotting was an additional duty naval Drachenballons were used for.

Drachenballons of the German Army were standard tan or dark green in color. On the sides and on the underside was an Iron Cross emblem to identify its operator. Allied countries would not have these emblems on their balloons and their exact colors are unknown. Russian Drachenballons were known to be white.

(Rolf Kranz)

A German Drachenballon prepares to go up, 1915.

The Drachenballon would see its first operational use in wartime in 1904 during the Russo-Japanese war. Imperial Russia had acquired several Drachenballons from Germany around the outbreak of the war, and would use them in the conflict. The first battle Drachenballons would be used in would be the Battle of Port Arthur. Aside from land usage, the balloons were also used by the Russian Navy, one such Drachenballon was used aboard the Armored Cruiser Rossia for observational duties and for directing fire of the main guns. The balloons would be used through the war until the final battle at Mukden.

(Australian War Memorial Photo collection, H13483)

A German soldier jumping from his observation balloon. German observers followed this procedure when their balloon was attacked by Allied aircraft.

Because of their importance as observation platforms, balloons were defended by anti-aircraft guns, groups of machine guns for low altitude defence and patrolling fighter aircraft. Attacking a balloon was a risky venture but some pilots relished the challenge. The most successful were known as balloon busters, including such notables as Belgium’s Willy Coppens, Germany’s Friedrich Ritter von Röth, America’s Frank Luke, and the Frenchmen Léon Bourjade, Michel Coiffard and Maurice Boyau. Many expert balloon busters were careful not to go below 1,000 feet (300 m) in order to avoid exposure to anti-aircraft guns and machine-guns.

First World War observation crews were the first to use parachutes, long before they were adopted by fixed-wing aircrews. These were a primitive type, where the main part was in a bag suspended from the balloon, with the pilot only wearing a simple body harness around his waist, with lines from the harness attached to the main parachute in the bag. When the balloonist jumped, the main part of the parachute was pulled from the bag, with the shroud lines first, followed by the main canopy. This type of parachute was first adopted by the Germans and then later by the British and French for their observation balloon crews.

Barrage Balloons in service during the Second World War

During the Second World War, Britain established a Balloon Command to protect cities and key targets such as industrial areas, ports and harbours. The balloons were designed to defend against German Stuka dive bombers operating at altitudes of 1.5 km/5,000 feet with the aim of forcing them to fly higher and into the range of concentrated anti-aircraft fire. By the summer of 1940 there were 1,400 barrage balloons in service, with a third of them protecting London. By 1944, there were 3,000 in use in the UK. They proved to be moderately effective against the V-1 flying bomb, which usually flew at an altitude of 600 metres/2,000 feet or lower, although these early cruise missiles had wire-cutters on their wings to counter balloons. 231 V-1s are officially claimed to have been destroyed by balloons.

In 1942 Canada and the USA conducted joint operations using barrage balloons to protect the sensitive locks and shipping channel at Sault Ste. Marie on the Great Lakes to deter potential air attacks. Between Aug and Oct 1942, severe storms caused some of the barrage balloons to break loose, and the trailing cables short-circuited power lines causing serious disruption to mining and manufacturing. In particular, the metals production vital to the war effort was disrupted. Canadian military historical records indicate that the “October incident, the most serious, caused an estimated loss of 400 tons of steel and 10 tons of ferro-alloys. Following these incidents, new procedures were put in place, which included stowing the balloons during the winter months, with regular deployment exercises and a standby team on alert to deploy the balloons in case of attack. (Wikipedia)

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 4950991)

Members of the Women’s Royal Canadian naval Service (WRCNS) visiting a barrage balloon site with The Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) operating the balloons inthe UK, 1944.

Post War

After the war, some surplus barrage balloons were used as tethered shot balloons for nuclear weapon tests throughout most of the period when nuclear weapons were tested in the atmosphere. The weapon or shot was carried to the required altitude slung underneath the barrage balloon, allowing test shots in controlled conditions at much higher altitudes than test towers. Project Mogul saw the use of high-altitude observation balloons to monitor Soviet nuclear tests.

New Brunswick connection:

Although fairly recent to the Maritimes, hot air ballooning has a rich history, with the first manned flight taking place on 21 November 1783 in Paris. Upon the balloon’s descent, its pilots were greeted with champagne, a tradition that has stood the test of time and deemed ballooning as “the champagne sport.” Ballooning didn’t take off in Canada until 1840 when Louis Lauriat left Saint John, New Brunswick, piloting a 1.5 hour flight.

On 10 August 1840, professor of chemistry and aerostatic exhibitions Louis Anslem Lauriat inflated his massive balloon “Star of the East” with hydrogen gas in a lot in Saint John, New Brunswick, ascended in its basket and drifted out of sight over the countryside. Louis Anselm Lauriat, (c. 1786 – c. 1857), was a Boston aeronaut who reportedly made 48 balloon ascensions during his lifetime. He was born in Marseilles, France, and came to America in the early 1800s, where he settled in Boston and established a business at the corner of Washington and Springfield Streets in Boston producing gold leaf. He also developed an interest in science and balloons, and began making ascensions of his own.

On 8 Sep 1856, Eugene Godard took three local men for a balloon flight from Montreal across the St. Lawrence River. Godard’s trio became Canada’s first aerial passengers. An ascent beginning in Watertown, NY, on 24 Sep 1858, and ending hours later in the Quebec bush seems to qualify as the first USA to Canada trans-border flight.