Warships of Italy: Regia Marina Cruisers Alberico da Barbiano, Alberto di Giussano, Armando Diaz, Bari, Bartolomeo Colleoni, Bolzano, Attilio Regolo, Giulio Germanico, Pompeo Magno, Scipione Africano, and Condottieri-class cruisers

Regia Marina Cruisers Alberico da Barbiano, Alberto di Giussano, Armando Diaz, Bari, Bartolomeo Colleoni, Bolzano, Attilio Regolo, Giulio Germanico, Pompeo Magno, Scipione Africano, and Condottieri-class cruisers

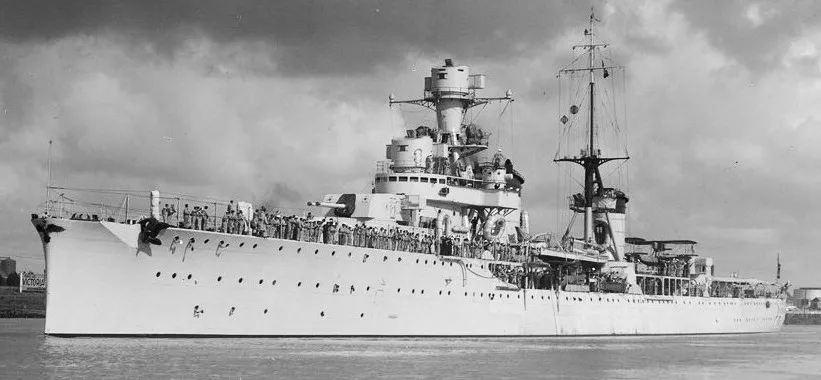

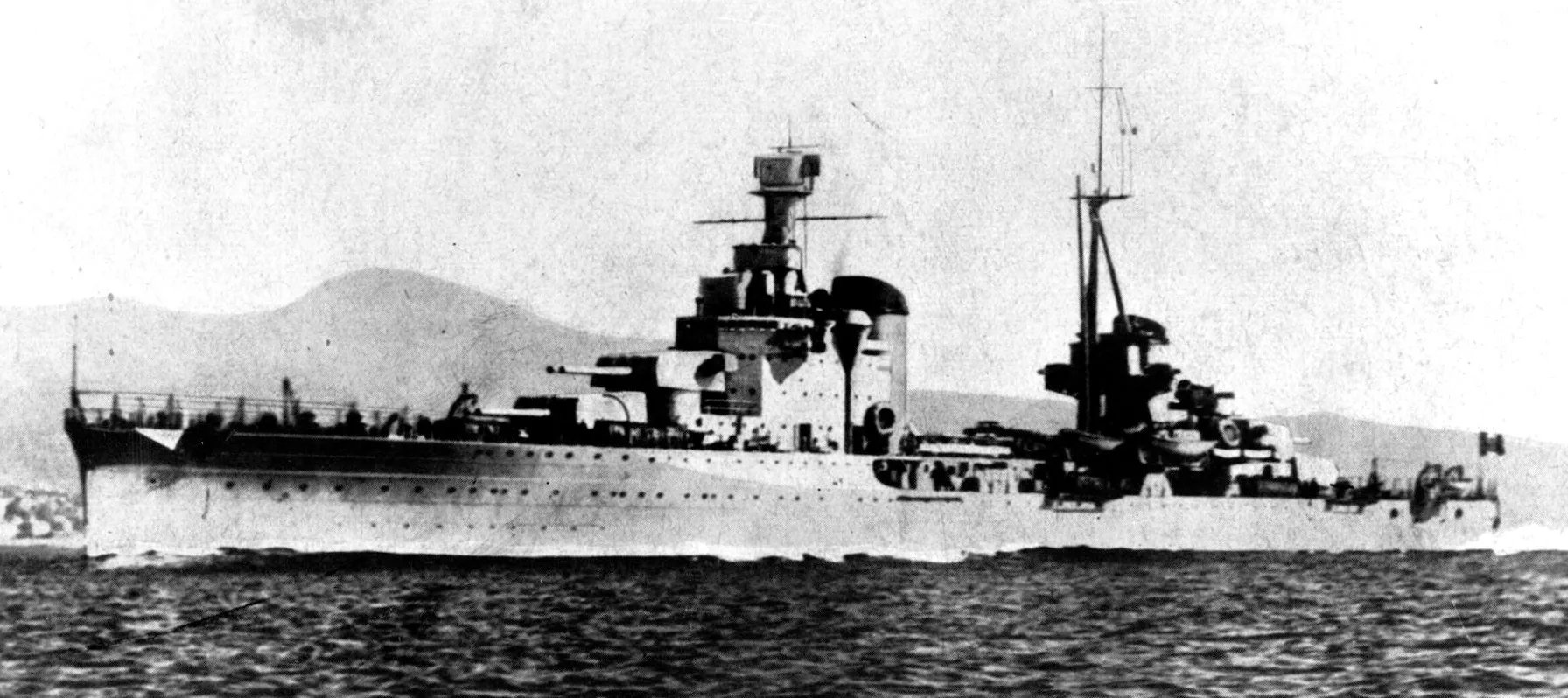

Italian cruiser Alberico da Barbiano

(Regia Marina Photo)

Alberico da Barbiano was an Italian Giussano-class light cruiser, that served in the Regia Marina during the Second World War. She was named after Alberico da Barbiano, an Italian condottiero of the 14th century.

During the Second World War, Alberico Da Barbiano was part of the 4th Cruiser Division. On 9 July 1940 Da Barbiano was present at the Battle of Calabria (Punto Stilo). In summer 1940 she also participated in some escort and minelaying missions between Italy and North Africa. Due to the weakness of the class, on 1 September 1940 she was assigned as a training ship in Pola, but on 1 March 1941 was returned to active service.In December 1941 the Italian naval staff, in the face of a deteriorating supply situation between Italy and Libya, decided to use the 4th Cruiser Division, then composed of Da Barbiano (flagship of ammiraglio di divisione Antonino Toscano, the commander of the Division) and her sister ship Alberto di Giussano, for an urgent transport mission to North Africa.Da Barbiano and Di Giussano left Taranto at 8:15 on 5 December 1941, reached Brindisi at 17:50 and there loaded about 50 tons of supplies, then proceeded to Palermo on 8 December, where they loaded an additional 22 tons of aviation fuel, which was especially needed in Libya (otherwise, aircraft based there would soon become unable to escort incoming convoys with vital supplies). The fuel, contained in unsealed barrels, was placed on the stern deck, thus posing great danger in case of enemy attacks (not only it would be set afire by mere strafing, but even by the flames of the ships' own guns, thus preventing the use of the stern turrets).

The two cruisers sailed unescorted from Palermo at 17:20 on 9 December, heading for Tripoli, but at 22:56 they were spotted by a British reconnaissance plane north of Pantelleria. The plane, which had located Toscano's ships thanks to Ultra intercepts, started to shadow them.[2] At 23:55 Toscano (who was at that time in the middle of the Sicilian Channel), since the surprise (required for the success of the mission) had vanished, heavy enemy radio traffic foreshadowed upcoming air strikes, and worsening sea conditions would delay his ships, further exposing them to British attacks, decided to turn back to base. Da Barbiano and Di Giussano reached Palermo at 8:20 on 10 December, after overcoming a British air attack off Marettimo. Toscano was heavily criticized by Supermarina for his decision to abort the mission.As for 13 December a new convoy operation, called M. 41, was planned, and the air cover by aircraft based in Libya would only be possible if they received new fuel, on 12 December it was decided that the 4th Division would attempt again the trip to Tripoli. The cruiser Giovanni delle Bande Nere was to join Da Barbiano and Di Giussano to carry more supplies, but she was prevented from sailing by a breakdown, thus her cargo had to be transferred to the other two cruisers. Da Barbiano and Di Giussano were overall loaded with 100 tons of aviation fuel, 250 tons of gasoline, 600 tons of naphtha and 900 tons of food stores, as well as 135 ratings on passage to Tripoli. As the stern of Da Barbiano (and, to a lesser extent, Di Giussano) was packed with fuel barrels, so thickly that it was not possible anymore to bring the guns to bear, Toscano held a last assembly with his staff and officers from both ships, where it was decided that, in case of encounter with enemy ships, the barrels would be discarded overboard, and then the cruisers would open fire (otherwise, the fuel would have been set afire by the firing of the cruisers' own guns).

Da Barbiano, Di Giussano and their only escort, the torpedo boat Cigno (a second torpedo boat, Climene, was left in the port due to a breakdown), sailed from Palermo at 18:10 on 12 December.[2] The 4th Division was ordered to pass northwest of the Aegadian Islands and then head for Cape Bon and follow the Tunisian coast; the ships would keep a speed of 22-23 knots (not more, because they were to spare part of their own fuel and deliver it at Tripoli).[2] Air cover, air reconnaissance and defensive MAS ambushes were planned to safeguard the mission.The British 4th Destroyer Flotilla, consisting of the destroyers HMS Sikh, HMS Maori, HMS Legion, and the Dutch destroyer HNLMS Isaac Sweers, (Commander G. H. Stokes), had departed Gibraltar on 11 December, to join the Mediterranean Fleet at Alexandria. By 8 December, the British had de-coded Italian C-38 wireless signals about the Italian supply operation and its course for Tripoli. The RAF sent a Wellington bomber on a reconnaissance sortie to sight the ships as a deception and on 12 December, the 4th Destroyer Flotilla, heading east from Gibraltar towards the Italian ships, was ordered to increase speed to 30 knots (56 km/h; 35 mph) and intercept.

In the afternoon of 12 December, a CANT Z. 1007 bis of Regia Aeronautica spotted the four destroyers heading east at an estimated speed of 20 knots, 60 miles (97 km) off Algiers; Supermarina was immediately informed but calculated that, even in the case the destroyers would increase their speed to 28 knots, they would have reached Cape Bon around 3:00 AM on 13 December, about one hour after the 4th Division, so Toscano (who learned of the sighting while he was still in harbour) was not ordered to increase speed or alter course to avoid them. Following new Ultra decodes, a new reconnaissance plane was sent and spotted Toscano's ships at sunset on 12 December, after which the 4th Destroyer Flotilla was directed to intercept the two cruisers, increasing speed to 30 knots. This speed, along with a one-hour delay that the 4th Division had accrued (and that Toscano omitted to report to Supermarina), frustrated all previous Supermarina calculations about the advantage that the 4th Division would have. At 22:23 Toscano was informed that he would possibly meet "enemy steamers coming from Malta", and at 23:15 he ordered action stations.The 4th Destroyer Flotilla sighted the Italian cruisers near Cap Bon, at 02:30 on 13 December.

At 2:45 on 13 December, seven miles off Cape Bon, the Italian ships heard the noise of a British plane (a radar-equipped Vickers Wellington, which located the ships and informed Stokes about their position), and at 3:15 they altered course to 157° to pass about one mile off Cape Bon. Five minutes later, Toscano suddenly ordered full speed ahead and to alter course to 337°, effectively reversing course; this sudden change disrupted the Italian formation, as neither Cigno (which was about two miles ahead of the cruisers) neither Di Giussano (which was following Da Barbiano in line) received the order, and while Di Giussano saw the flagship reverse course and imitated her (but remained misaligned), Cigno did not noticed the change till 3:25, when she also reversed course, but remained much behind the two cruisers. The reasons for Toscano's decision of reverse course have never been fully explained: it has been suggested that, upon realizing that he had been spotted by aircraft, he decided to turn back like on 9 December (but in this case, a course towards the Aegadian islands would have made more sense, instead that the northwesterly course ordered by Toscano; and the change was suddenly ordered more than 30 minutes after the cruisers had been spotted); that he wanted to mislead the reconnaissance plane about his real course, wait for it to go away, and then go back on the previous course to Tripoli; that he thought from the noise that torpedo bombers were coming, and he wanted to get in more open waters (farther away from the shore and the Italian minefields) to obtain more freedom of manoeuvre; or that he had spotted the Allied destroyers astern and, not wanting to present his stern to them (as the aft turrets were unusable and most fuel was stowed there), he decided to reverse course to fire on them with his bow turrets (upon ordering the change of course, he also ordered the gunners to keep ready).

Stokes's destroyers were, indeed, just off Cape Bon by then, and they had spotted the Italian ships. Arriving from astern, under the cover of darkness and using radar, the British ships sailed close inshore and surprised the Italians who were further out to sea, by launching torpedoes from short range. The course reversal accelerated the approach between the two groups, and the Allied destroyers attacked together; Sikh fired her guns and four torpedoes against Da Barbiano (the distance was less than 1,000 meters) and Legion did the same, while Maori and Isaac Sweers attacked Di Giussano. Toscano ordered full speed and to open fire (and also, to Di Giussano, to increase speed to 30 knots) and Da Barbiano also started a turn to port (on orders from the ship's commanding officer, Captain Giorgio Rodocanacchi), but at 3:22, before her guns were able to fire (only some machine guns managed to), the cruiser was hit by a torpedo below the forwardmost turret, which caused her to list to port.

Da Barbiano was then raked with machine gun fire, which killed or wounded many men and set fire to the fuel barrels, and hit by a second torpedo in the engine room. At 3.26 Maori also fired two torpedoes at Da Barbiano, and opened fire with her guns, hitting the bridge. Moments after, the cruiser was hit by another torpedo in the stern (possibly launched by Legion); meanwhile, Di Giussano was disabled as well. Da Barbiano rapidly listed to port, while the fires quickly spread all over the ship and also into the sea, fueled by the floating fuel, and the crew started to abandon ship. At 3:35, Da Barbiano capsized and sank in a sea of flame. 534 men, including Admiral Antonino Toscano, the commander of Italian Fourth Naval Division, his entire staff and the commanding officer of Alberico Da Barbiano, Captain Giorgio Rodocanacchi, were lost with the ship. 250 survivors reached the Tunisian coast or were picked up by rescuing vessels. (Wikipedia)

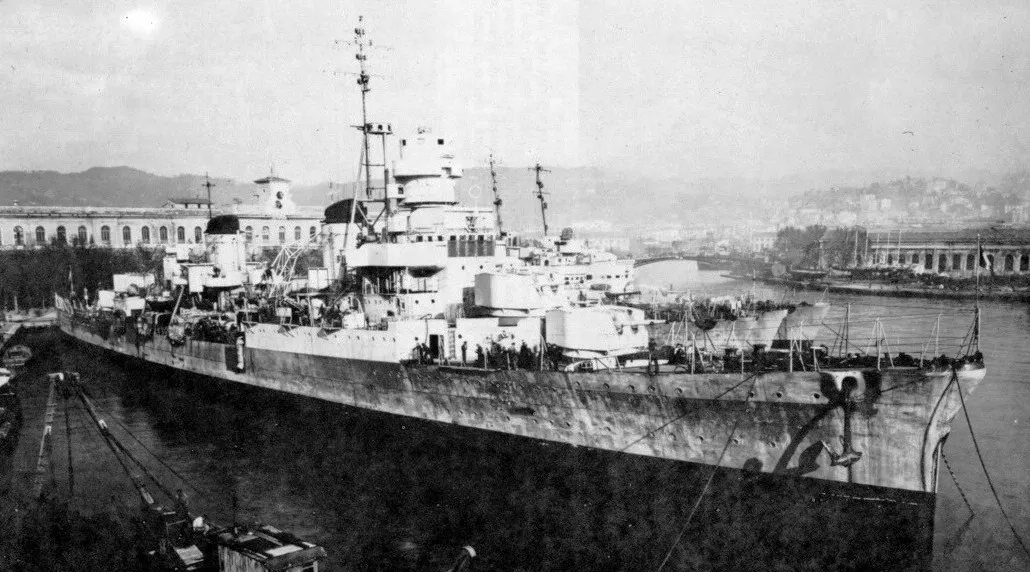

Italian cruiser Alberto di Giussano

(Regia Marina Photo)

Alberto di Giussano (named after Alberto da Giussano, a fictional[2] medieval military leader condottiero) was an Italian Giussano-class cruiser, which served in the Regia Marina during the Secobnd World War. She was launched on 27 April 1930.She participated in the normal peacetime activities of the fleet in the 1930s as a unit of the 2nd Squadron, including service in connection with the Spanish Civil War. On 10 June 1940 she was part of the 4th Cruiser Division, with the 1st Squadron, together with her sister ship Alberico da Barbiano and was present at the Battle of Punta Stilo in July. She carried out a minelaying sortie off Pantelleria in August, and for the rest of the year acted as distant cover on occasions for troop and supply convoys to North Africa.On 12 December 1941 she left port together with her sister ship Alberico da Barbiano. Both she and her sister were being used for an emergency convoy to carry gasoline for the German and Italian mobile formations fighting with the Afrika Korps. Jerrycans and other metal containers filled with gasoline were loaded onto both cruisers and were placed on the ships' open decks. The thinking behind using these two cruisers for such a dangerous mission was that their speed would act as a protection. Nonetheless, the ships were intercepted by four Allied destroyers guided by radar on 13 December 1941, in the Battle of Cape Bon. Alberto di Giussano was able to fire only three salvos before being struck by a torpedo amidships and hit by gunfire, which left her disabled and dead in the water. After vain struggle to halt the fire, the crew had to abandon the ship, which broke in two and sank at 4.22. 283 men out of the 720 aboard lost their lives. The ship's commanding officer, Captain Giovanni Marabotto, was among the survivors. (Wikipedia)

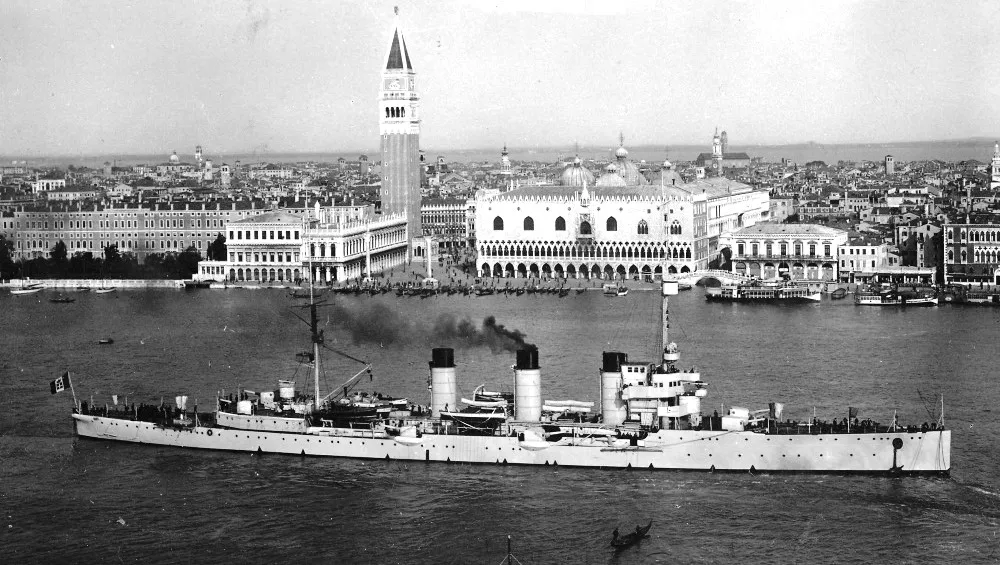

Italian cruiser Armando Diaz

(State Library of Victoria Photo)

Armando Diaz was a light cruiser of the Condottieri class and the sister-ship of the Luigi Cadorna. She served in the Regia Marina during the Second World War. She was built by OTO, La Spezia, and named after Armando Diaz, an Italian Field Marshal of the First World War.She was launched on 29 April 1933 and served in the Mediterranean after her completion. From 1 September 1934 until February 1935 she made a cruise to Australia and New Zealand.During the Spanish Civil War she served in the western Mediterranean and was based at Palma de Mallorca and Melilla. In July 1940, she was present at the Battle of Calabria, also called the battle of Punta Stilo. In October she took part in a mission to Albania, and in December she came under direct orders of Supermarina (Naval Headquarters) for special duties in connection with the protection of traffic to Albania from January 1941. However, the following month an important supply convoy to Tripoli required her use for cover, in company with the light cruiser Giovanni dalle Bande Nere and some destroyers.In the course of this operation the ship was torpedoed and sunk by the British submarine HMS Upright off the Kerkennah Islands in the early hours of 25 February. It took the Italian cruiser only six minutes to sink after her magazine detonated, with the loss of 484 men. (Wikipedia)

.webp)

(Regia Marina Photo)

Italian light cruiser Armando Diaz on a visit to Sydney, Australia, 27 October 1934.

Italian cruiser Bari

(Regia Marina Photo)

SMS Pillau was a light cruiser of the Imperial German Navy. The ship, originally ordered in 1913 by the Russian navy under the name Maraviev Amurskyy, was launched in April 1914 at the Schichau-Werke shipyard in Danzig (now Gdańsk, Poland). However, due to the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, the incomplete ship was confiscated by Germany and renamed SMS Pillau for the East Prussian port of Pillau (now Baltiysk, Russia). Pillau was commissioned into the German Navy in December 1914. She was armed with a main battery of eight 15 cm SK L/45 (5.9-inch) guns and had a top speed of 27.5 kn (50.9 km/h; 31.6 mph). One sister ship was built, Elbing.After the end of the First World War, Pillau was ceded to Italy as a war prize in 1920. Renamed Bari, she was commissioned in the Regia Marina (Royal Navy) in January 1924. She was modified and rebuilt several times over the next two decades. In the early years of the Second World War, she provided gunfire support to Italian troops in several engagements in the Mediterranean. In 1943, she was slated to become an anti-aircraft defense ship, but while awaiting conversion, she was sunk by USAAF bombers in Livorno in June 1943. The wreck was partially scrapped by the Germans in 1944, and ultimately raised for scrapping in January 1948. (Wikipedia)

Italian cruiser Bartolomeo Colleoni

(Regia Marina Photo)

Bartolomeo Colleoni was an Italian Giussano-class light cruiser, that served in the Regia Marina (Royal Navy) during the Second World War. She was named after Bartolomeo Colleoni, an Italian military leader of the 15th century. She was sunk at the Battle of Cape Spada early in the war.

Bartolomeo Colleoni and Giovanni delle Bande Nere left Tripoli on the evening of 17 July and sailed to the north of Crete, bound for the Aegean. On the 19th, the four British destroyers HMS Hyperion, Ilex, Hero, and Hasty were sent on an anti-submarine patrol in the area, while the Australian light cruiser HMAS Sydney and the British destroyer Havock searched the Gulf of Athens. At around 06:00 on 19 July, the Italians spotted the four British destroyers off Cape Spada of western Crete, which were some 17,000 m (19,000 yd) away; Sydney and Havock were around 60 nautical miles (110 km; 69 mi) to the north. The British ships immediately signaled Sydney and turned to flee at high speed. The Italian commander, Rear Admiral Ferdinando Casardi aboard Giovanni delle Bande Nere, ordered his ships to pursue the retreating British ships, believing them to be part of the escort for a convoy he hoped to attack. At 06:27, the Italian cruisers opened fire on the destroyers, but the faster destroyers were able to pull out of range without having been hit.

At around this time, a Greek freighter passed between the formations but quickly withdrew from the area.Casardi pursued the British blindly, deciding not to launch any of his reconnaissance aircraft (both because of the sea state and not wanting to slow down to launch them), and he was also not supported by any land based aircraft in the area. As a result, they had no way to know that Sydney was in the area, and when she arrived on the scene at around 07:30 and opened fire, it took the Italians completely by surprise. The Australian cruiser had opened fire from a range of about 12,000 m (13,000 yd) while in the middle of a fog bank; almost immediately, she hit Giovanni delle Bande Nere near her aft funnel. The Italian cruisers quickly returned fire, but had difficulty locating the target in the fog, as they only had Sydney's muzzle flashes to aim at. They also rolled badly in the heavy seas, which further hampered their gun laying.

Captain Collins of Sydney detached Havock to join the other destroyers, Collins ordered to make a torpedo attack on the cruisers. Casardi responded by turning his ships south and then southwest to move to less restricted waters further from Crete. As the Italians withdrew, Sydney alternated fire between the two cruisers, depending on which was more visible, but she focused her fire on Bartolomeo Colleoni, as she was generally closer.At 08:24, Sydney struck Bartolomeo Colleoni with a salvo of 152 mm shells; one of the rounds jammed her rudder in the neutral position. The ship was now unable to steer, but she remained on the course she had been steaming. Shortly thereafter, another salvo from Sydney hit the ship amidships, causing extensive damage and starting several fires. One shell struck her conning tower and killed much of the bridge crew. The ship lost speed, which allowed the British destroyers to come into range. Further hits disabled two of the boilers and destroyed the main steam condenser, which was used to feed water back into the boilers. Without water to boil, the engines quickly shut down, leaving Bartolomeo Colleoni dead in the water. The ammunition hoists for her main battery guns were also disabled. Her 100 mm guns kept firing, as they could be operated manually. Within six minutes of the first hit, the ship had been effectively neutralized and Captain Umberto Novaro issued the order to abandon ship.At about that time, Ilex and Havock closed to launch torpedoes at the stricken cruiser, though their initial attacks missed. Hyperion joined the two destroyers, which had launched a further round of torpedoes, one of which hit Bartolomeo Colleoni. The torpedo, from Ilex, struck forward and blew off the first 30 m (98 ft) of her bow.

Casardi circled back at 08:50 to attempt to come to her aid, but quickly determined that the situation was hopeless, so he turned back to the west and fled at high speed.[18] Hyperion then launched a torpedo that struck amidships. The second hit caused serious flooding, and Bartolomeo Colleoni quickly capsized and sank. Sydney, Hero, and Hasty continued the pursuit of Giovanni delle Bande Nere, but Ilex, Havock, and Hyperion approached the area that survivors from Bartolomeo Colleoni were floating. They picked up 525 men, of whom eight died of their wounds and were buried at sea. The British had to suspend rescue efforts when Italian bombers appeared and attacked the ships. A further fifty men attempted to swim to the coast of Crete, but only seven survived to be picked up by a Greek fishing boat. Four more men, including captain Novaro, died aboard hospital ship Maine at Alexandria, Egypt. These men were buried there, and the captains of Sydney and the destroyers served as the pallbearers. In total, 121 out of a crew of 643 were killed in the sinking. (Wikipedia)

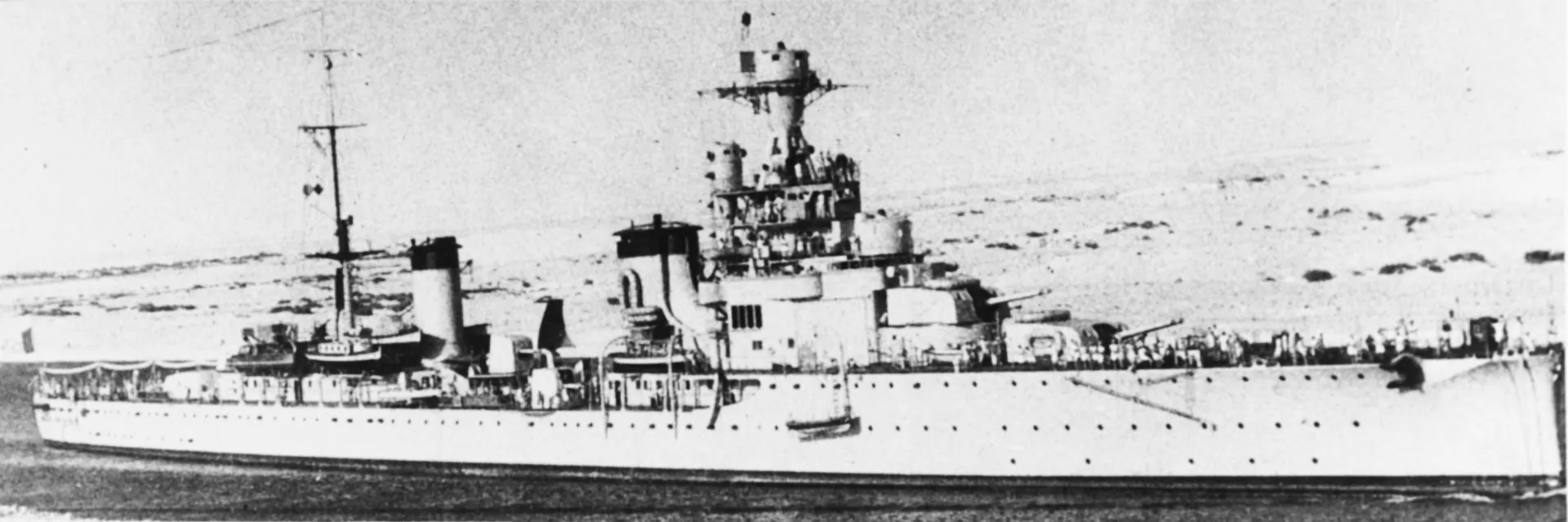

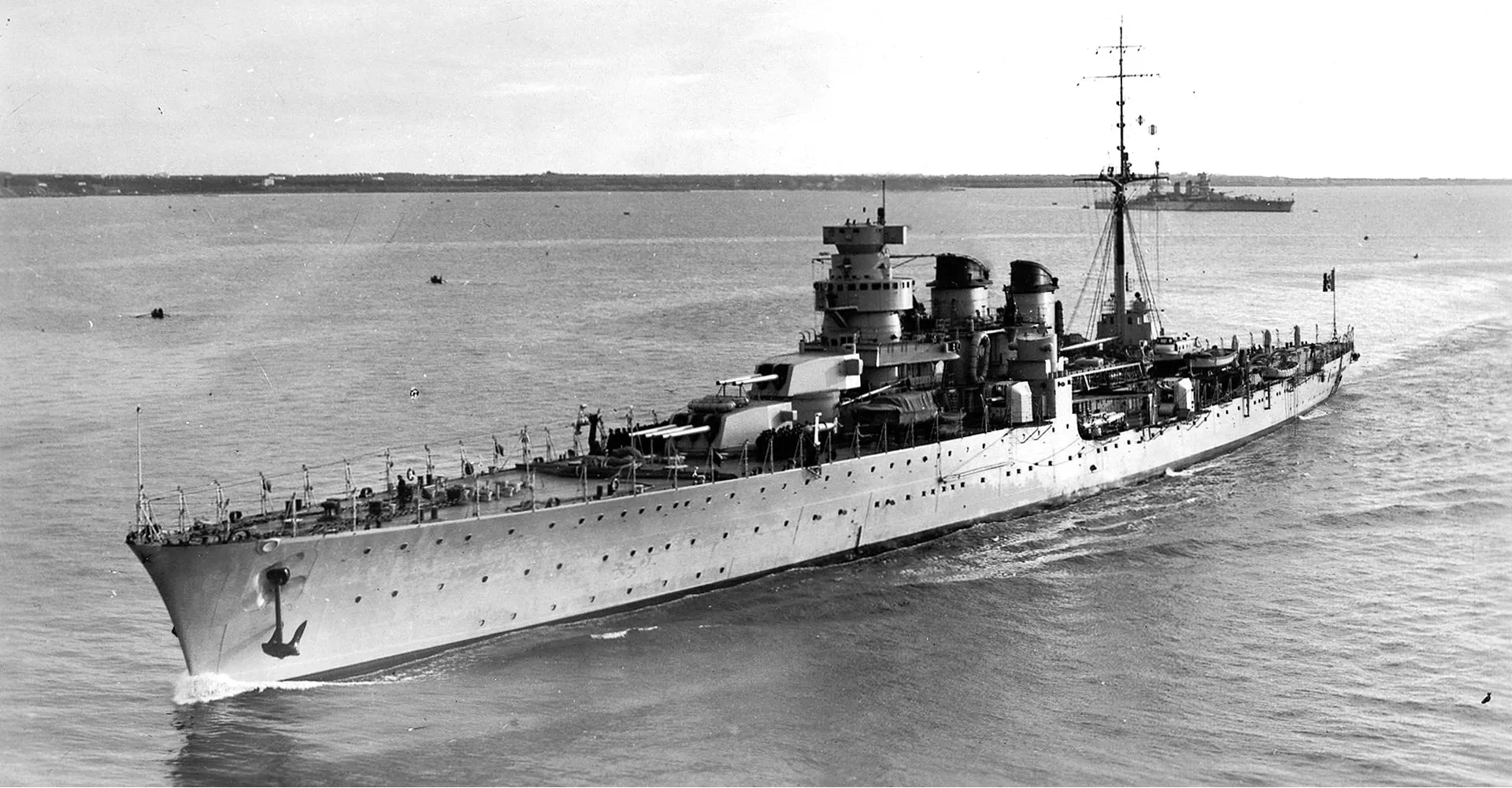

Italian cruiser Bolzano

(Regia Marina Photo)

Bolzano was a unique heavy cruiser, sometimes considered to be a member of the Trento class, built for the Italian Regia Marina (Royal Navy) in the early 1930s, the last vessel of the type to be built by Italy. A modified version of the earlier Trento class, she had a heavier displacement, slightly shorter length, a newer model of 203 mm (8 in) gun, and a more powerful propulsion system, among other differences influenced by the Zara class that had followed the Trentos. Bolzano was built by the Gio. Ansaldo & C. between her keel laying in June 1930 and her commissioning in August 1933.Bolzano had a fairly uneventful peacetime career, which primarily consisted of naval reviews for Italian and foreign dignitaries. She saw extensive action in the first three years of Italy's participation in the Second World War. She took part in the Battles of Calabria, Taranto, Cape Spartivento, and Cape Matapan. The ship was lightly damaged at Calabria, but she emerged from the other engagements unscathed. She also frequently escorted convoys to North Africa in 1941 and 1942 and patrolled for British naval forces in the central Mediterranean Sea.

Bolzano was torpedoed twice by British submarines; the first, in July 1941, necessitated three months of repairs. The second, in August 1942, caused extensive damage and ended the ship's career. She was eventually towed back to La Spezia, where repairs were to be completed. Resources were unavailable, however, and Bolzano remained there, out of action. Plans to convert her into a hybrid cruiser-aircraft carrier came to nothing for the same reason. After Italy surrendered to the Allies in September 1943, La Spezia was occupied by German forces; to prevent them from using her as a blockship, Italian and British frogmen sank Bolzano using Chariot manned torpedoes in June 1944. The Italian Navy ultimately raised the ship in September 1949 and broke her up for scrap. (Wikipedia)

(Regia Marina Photo)

Italian cruiser Bolzano.

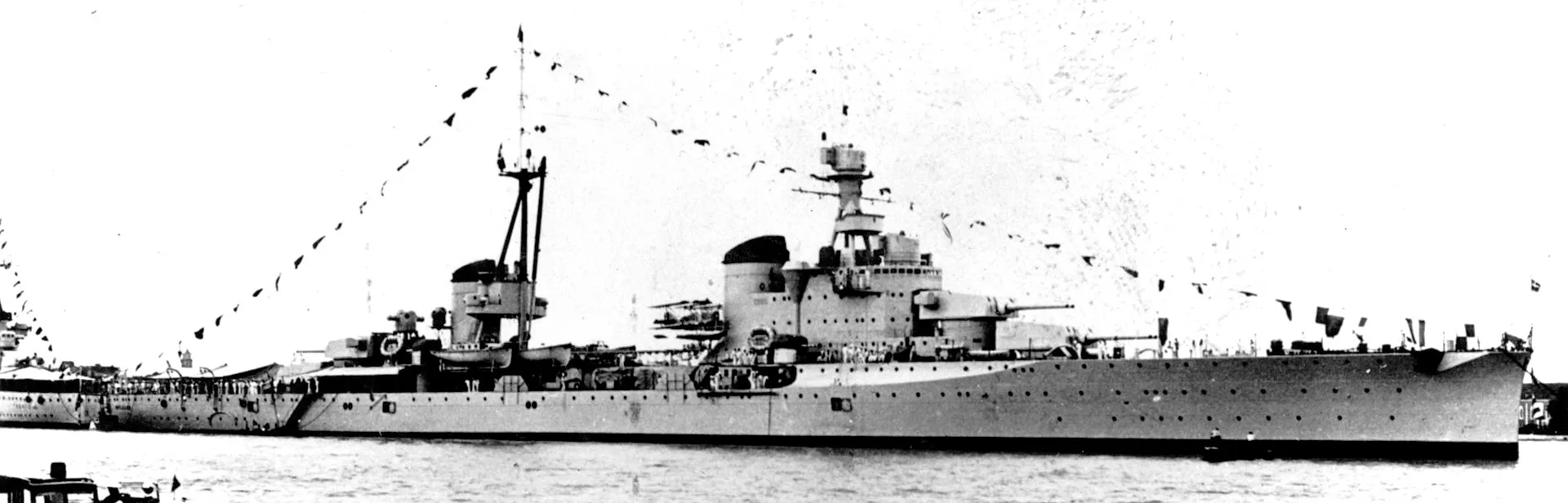

Capitani Romani-class cruiser

The Capitani Romani class was a class of light cruisers acting as flotilla leaders for the Regia Marina (Italian Navy). They were built to outrun and outgun the large new French destroyers of the Le Fantasque and Mogador classes. Twelve hulls were ordered in late 1939, but only four were completed, just three of these before the Italian armistice in 1943. The ships were named after prominent ancient Romans (Capitani Romani), (Roman Captains).

Italian cruiser Attilio Regolo

(Regia Marina Photo)

Atillio Regolo was commissioned in August 1942 in Livorno. She was torpedoed by the submarine HMS Unruffled on 7 November 1942, and remained in drydock for several months with her bow shattered. She was interned in Port Mahon in the island of Menorca, Spain, after the armistice on 9 September 1943. In Italian service, the ship was named Attilio Regolo after Marcus Atilius Regulus the Roman statesman and general who was a consul of the Roman Republic in 267 BC and 256 BC.After the Peace Treaty on 10 February 1947, she and her sister ship Scipione Africano were transferred to France as war reparations (Scipione Africano was renamed Guichen). The ships were extensively rebuilt for the French Navy by La Seyne dockyard with new anti-aircraft-focused armament and fire-control systems in 1951–1954. Chateaurenault (D 606) was a French Capitani Romani-class light cruiser, acquired as war reparations from Italy in 1947 which served in the French Navy from 1948 to 1961. She was named in honour of François Louis de Rousselet, Marquis de Châteaurenault. (Wikipedia)

Italian San Giorgio-class cruisers

The San Giorgio class was a class of two destroyers of the Italian Navy. They entered service in 1955, with the last one being decommissioned in 1980. Formerly Capitani Romani-class cruisers of the Regia Marina (Royal Italian Navy) during the Second World War, they were rebuilt as destroyers during the Cold War. San Giorgio (ex Pompeo Magno) was the first to enter service in 1955 and was modified again from 1963 to 1965 to become a training ship until 1980. San Marco (ex Giulio Germanico) was scuttled by the Germans after the incomplete ship fell into German hands following the Italian Armistice. Following the war, the vessel was raised, rebuilt and renamed and entered service in 1956. San Marco served until 1971. (Wikipedia)

Italian cruiser Giulio Germanico

(Regia Marina Photo)

Giulio Germanico was captured by the Germans in Castellammare di Stabia while under completion, and scuttled by them on 28 September 1943. She was raised and completed for the Italian Navy after the war. Renamed San Marco, she served as a destroyer leader until her decommission in 1971. Giulio Germanico cruiser

Giulio Germanico was built in the Royal Shipyard of Castellammare di Stabia. Laid down in 1939 and launched in 1941, the cruiser was completing the set-up when the armistice of 8 September was signed. Falling into the hands of the Germans who had taken control of the shipyard, the ship was scuttled when the following 28 September the German occupation troops left the city. After the war the hull of Giulio Germanico was recovered in the port of Castellammare and marked the designation FV 2. Given the good overall condition of the hull in 1950 it was decided to rebuild the ship as a destroyer and renamed San Marco. Once the work was completed, the ship entered service in the Italian Navy on 1 January 1956 with the pennant number D 563, serving until 1971 when it was disarmamed.

Italian cruiser Pompeo Magno

.webp)

(Regia Marina Photo)

Pompeo Magno entered service in the Regia Marina (Royal Italian Navy) in 1943 shortly before the armistice. After removal from the Navy list it was marked by the designation FV 1. In 1950 it was chosen for reconstruction as a destroyer and renamed San Giorgio. Once the work was completed, the ship entered service in the Italian Navy on 1 July 1955 with the pennant number D 562. From 1963 and until 1965, San Giorgio was again subjected to modification works at the Arsenal of La Spezia to be transformed into a training ship for the students of the Naval Academy of Livorno, carrying out this task until it was disarmed in 1980.

Italian Capitani Romani-class light cruisers

The Capitani Romani class was a class of light cruisers acting as flotilla leaders for the Regia Marina (Italian Navy). They were built to outrun and outgun the large new French destroyers of the Le Fantasque and Mogador classes. Twelve hulls were ordered in late 1939, but only four were completed, just three of these before the Italian armistice in 1943. The ships were named after prominent ancient Romans (Capitani Romani). The Capitani Romani class were originally designed as scout cruisers for ocean operations ("ocean scout", esploratori oceanici), although some authors consider them to have been heavy destroyers.

(Regia Marina Photo)

Italian light cruiser Scipione Africano

Scipione Africano was an Italian Capitani Romani-class light cruiser, which served in the Regia Marina during the Second World War. As she was commissioned in the spring of 1943, the majority of her service took place on the side of the Allies - 146 wartime missions after the Armistice of Cassibile versus 15 before. She remained commissioned in the Italian navy after the war, until allocated to France as war reparations by the Paris Peace Treaties of 1947. Scipione Africano was decommissioned from the Marina Militare in August 1948 and subsequently commissioned into the Marine Nationale as Guichen, after briefly being known as S.7.Scipione Africano was named after Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus, the Roman general and later consul. Her name under French service was in honour of Luc Urbain de Bouëxic, comte de Guichen. (Wikipedia)

Uncompleted Capitani Romani–class cruisers

Caio Mario. Captured by the Germans in La Spezia, with only the hull completed; used as a floating oil tank and scuttled in 1944.

Claudio Druso, Nero Claudius Drusus; scrapped between 1941 and February 1942.

Claudio Tiberio Emperor Tiberius; scrapped between November 1941 and February 1942.

Cornelio Silla Lucius Cornelius Sulla. Captured by the Germans in Genoa while fitting out; sunk in an air raid in July 1944.

Ottaviano Augusto Emperor Augustus. Captured by the Germans in Ancona while under completion; sunk in an air attack on 1 November 1943.

Paolo Emilio Lucius Aemilius Paullus Macedonicus; scrapped between October 1941 and February 1942.

Ulpio Traiano Emperor Trajan. Sunk 3 January 1943 by British human torpedo attack while fitting out in Palermo.

Vipsanio Agrippa Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa; scrapped between July 1941 and August 1942.

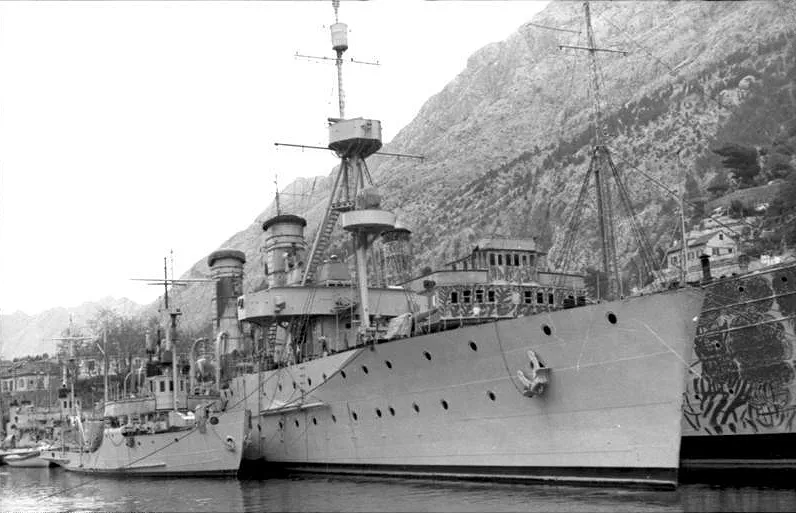

Italian cruiser Cattaro

(Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-185-0116-27A)

Yugoslavian cruiser Dalmacija (ex. German Niobe, later used by the Italians as Cattaro, then by the Germans as Niobe) and minelayer Mljet and Meljine (left)

Cattaro was initially the German SMS Niobe, the second of ten Gazelle-class light cruisers that were built for the German Kaiserliche Marine ('Imperial Navy') in the late 1890s and early 1900s. In 1925, Germany sold the ship to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later Yugoslavia). There, she was renamed Dalmacija and served in the Royal Yugoslav Navy until April 1941, when she was captured by the Italians during the Axis invasion of Yugoslavia. Renamed Cattaro, she served in the Italian Regia Marina (Royal Navy) until the Italian surrender in September 1943. She was then seized by the German occupiers of Italy, who restored her original name. She was used in the Adriatic Sea briefly until December 1943, when she ran aground on the island of Silba, and was subsequently destroyed by British motor torpedo boats. The wreck was ultimately salvaged and broken up for scrap between 1947 and 1952. (Wikipedia)

Condottieri-class cruiser

The Condottieri class was a sequence of five light cruiser classes of the Regia Marina (Italian Navy), although these classes show a clear line of evolution. They were built before the Second World War to gain predominance in the Mediterranean Sea. The ships were named after condottieri (military commanders) of Italian history.

Alberto di Giussano.

Alberico da Barbiano.

Bartolomeo Colleoni.

.webp)

(Regia Marina Photo)

Giovanni delle Bande Nere.

(Regia Marina Photo)

Luigi Cadorna.

Armando Diaz.

(State Library of Victoria Photo)

Raimondo Montecuccoli.

Muzio Attendolo.

Emanuele Filiberto Duca d'Aosta.

(Regia Marina Photo)

Eugenio di Savoia.

(Regia Marina Photo)

Luigi di Savoia Duca degli Abruzzi.

(Regia Marina Photo)

Luigi di Savoia Duca degli Abruzzi.

(Regia Marina Photo)

Giuseppe Garibaldi

The first group, the four Giussanos, were built to counter the French large destroyers (contre-torpilleurs), the first being the 2,500 ton Le Fantasque-class, and therefore they featured very high speed, in exchange for virtually no armour protection. The following two Cadornas retained the main characteristics, with minor improvements to stability and hull strength. Major changes were introduced for the next pair, the Montecuccolis. About 2,000 tons heavier, they had significantly better protection, and upgraded power-plants to maintain the required high speed.The two Duca d'Aostas continued the trend, thickening the armour and improving the power plant again.The final pair, the Luigi di Savoia Duca degli Abruzzis completed the transition, sacrificing a little speed for good protection (their armour scheme was the same of the Zara-class heavy cruisers) and for two more 6-inch /55 guns.

All ships served in the Mediterranean during the Second World War. The ships of the first two subclasses (with the exception of Luigi Cadorna) were all lost by 1942, primarily to enemy torpedoes (with Bartolomeo Colleoni sunk by destroyers at the Battle of Cape Spada after being crippled by HMAS Sydney, Alberico da Barbiano and Alberto di Giussano suffering a similar fate at in a night action of the Battle of Cape Bon, Giovanni delle Bande Nere sunk by British submarine HMS Urge, and Armando Diaz sunk by the British submarine HMS Upright) that led many authors (including Preston) to question their real value as fighting ships. The subsequent vessels fared considerably better with all surviving the war, except Muzio Attendolo (torpedoed in August 1942 and sunk by an Allied bombing in December 1942). After the end of the war, Eugenio di Savoia and Emanuele Filiberto Duca d'Aosta were given to the Greek Navy and the Soviet Navy respectively as war reparations; Luigi Cadorna was quickly stricken, Raimondo Montecuccoli became a training ship, and the Luigi di Savoia Duca degli Abruzzi subclass served on in the Marina Militare until the 1970s, with Giuseppe Garibaldi becoming the first European guided missile cruiser in 1961. (Wikipedia)