(Mike Freer – Touchdown Aviation Photo)

English Electric Canberra TT1.

The English Electric Canberra is a British first-generation jet powered medium bomber. It was developed by English Electric during the mid-to-late 1940s in response to a 1944 Air Ministry requirement for a successor to the wartime de Havilland Mosquito fast bomber. Among the performance requirements for the type was an outstanding high-altitude bombing capability and high speed. These were partly accomplished by making use of newly developed jet propulsion technology. When the Canberra was introduced to service with the Royal Air Force (RAF), the type’s first operator, in May 1951, it became the service’s first jet-powered bomber.

In February 1951, a Canberra set another world record when it became the first jet aircraft to make a non-stop transatlantic flight. Throughout most of the 1950s, the Canberra could fly at a higher altitude than any other aircraft in the world and in 1957, a Canberra established a world altitude record of 70,310 feet (21,430 m). Due to its ability to evade the early jet interceptor aircraft and its significant performance advancement over contemporary piston-engine bombers, the Canberra became a popular aircraft on the export market, being procured for service in the air forces of many nations both inside and outside of the Commonwealth of Nations. The type was also license-produced in Australia by the Government Aircraft Factories and by USAF Martin as the B-57 Canberra. The latter produced both the slightly modified B-57A Canberra and the significantly updated B-57B.

In addition to being a tactical nuclear strike aircraft, the Canberra proved to be highly adaptable, serving in varied roles such as tactical bombing and photographic and electronic reconnaissance. Canberras served in the Suez Crisis, Vietnam War, Falklands War, Indo-Pakistani wars and numerous African conflicts. In several wars, each of the opposing sides had Canberras in their air forces.

The Canberra had a lengthy service life, serving for more than 50 years with some operators. In June 2006, the RAF retired the last of its Canberras, 57 years after its first flight. “Three of the USAF Martin B-57 variant remain in service, performing meteorological and re-entry tracking work for NASA, as well as providing electronic communication (Battlefield Airborne Communications Node or BACN) testing for deployment to Afghanistan”. (Wikipedia)

On 3 May 1966, RCAF Flight Lieutenant George Russell Jenkins, CD, was killed in a flying accident (KIFA) while flying an RAF Canberra B.2 (Serial No. WH857), No. 97 (Straits Settlements) Squadron Royal Air Force. The Canberra stalled while attempting to overshoot from a misjudged asymmetric approach to Watton, Norfolk. It cartwheeled and burnt out short of the runway. The navigator and the AEO were ejected at ground level but the navigator was killed. The pilot did not eject and was killed in the crash.

Crew: AEO: Flt Lt Ken Topaz injured. Pilot: Flt Lt R. Jackson (killed). Navigator: Flt Lt R. Jenkins. RCAF (killed). Jenkins was flying his last sortie with the RAF before returning to Canada. When he ejected, Flt Lt Topaz became the first AEO to eject from an RAF aircraft. (https://aviation-safety.net/wikibase/21042)

Flight Lieutenant Topaz recounted his experience with the crash:

The 3rd of May 1966 was a sunny morning as the crew of Canberra B2, WH857 was flying on an Electronic Counter Measures Training flight. Soon after launch a piece of mission required equipment failed rendering the mission incomplete. To get some value out of the flight, the pilot decided to carry out a simulated engine out approach. They began the radar controlled letdown and were soon approaching the field. Flt. LT. Ken Topaz, the Air Electronics officer on board picks up the story:”Once we had settled down onto the radar approach I busied myself with my pre-landing checks, making sure that all my equipment was shut down correctly, this procedure which also entailed my tightening my harness for landing usually took about a couple of minutes.I heard the radar controller announce “you are one mile from touch down, look ahead and land” this was standard patter. At this point the navigator who was sitting close by on my left drew my attention to the air speed indicator which was reading 85 knots and falling rapidly (at this weight we should have been doing about 110 knots. Nothing was said because at the same time the pilot applied full power to both engines very rapidly, I was looking forward and saw the RPM gauges winding up, but the starboard engine (which had been set to zero thrust for the asymmetric practice) must have flamed out as the RPM unwound.

The aircraft, which was very low by this time, rolled very rapidly to starboard and then flicked back to port, the port wingtip struck the ground as the aircraft rolled almost vertical, cart wheeled and destroyed itself just to the left of the main runway.Between the time that the wingtip hit and the nose of the Canberra struck the ground, both the navigator and I ejected (again not a word was said!) As the ejector seats in the rear of the Canberra are side by side the seats are angled slightly to ensure that the seats separate as they leave the aircraft. The navigator being on the port side effectively ejected into the ground and died shortly after. Myself, being on the starboard had a degree of upward motion and separated from the seat (at what height no one knows but speculation is about 20 feet) Although not fully conscious due to the acceleration of the seat, I was immediately fully aware as I hit the ground. It would appear that I landed on my feet with absolutely no forward motion whatsoever as I was able to stop myself toppling with just one hand on the ground on which I now found myself sitting, or rather on my still fully packed parachute. The precise time of impact was 10:44 as the first thing I did was look at my watch, seems strange but it seemed important at the time.

The first person on the scene was my Squadron Commander who appeared out of the smoke, he paused for a moment and then ran past me, I didn’t realise that the Navigator was just behind me and obviously looking a lot worse than I did. The next person was the Station Dentist, who had been driving around the peri track, he appeared on the scene waving a knife with which, despite my protestations about the destruction of government property, he proceeded to use to cut me out of my harness. “I’ve been carrying this thing for years,” he said, “and am determined to use it now!” As you can see from the cut cords on the parachute he did a good job. I suppose I must have been in shock, but at no time did I feel any pain and the worst part of the incident was the ride in a rather bumpy ambulance to the RAF Hospital at Ely, it seemed to take an awfully long time. The pilot had stayed with the aircraft and was killed instantly in the wreck.

I sustained two broken ankles, a broken right hip joint, a fractured pelvis and minor damage to my spine. After about 18 months of hospitalisation and rehabilitation I returned to flying, albeit I was banned from further aircraft fitted with ejector seats. “So, in this case the Martin-Baker Mk. 1CN ejection seat did function far beyond what it was designed for, which was a minimum ejection altitude of 1000 feet and a minimum airspeed of 125 knots. It gave Flt. LT. Ken Topaz a chance at life. These cases are extremely rare, and rarer still are the ones without injury. The case for the Navigator was complicated by his drogue chute becoming entangled with the jettisoned hatch cover. In FltLt Topaz’s case, the majority of his forward velocity was cancelled by the catapult stroke of the seat. (https://www.pprune.org/military-aviation/120127-other-e-e-classic-canberra-merged-23rd-july-04-a.html)

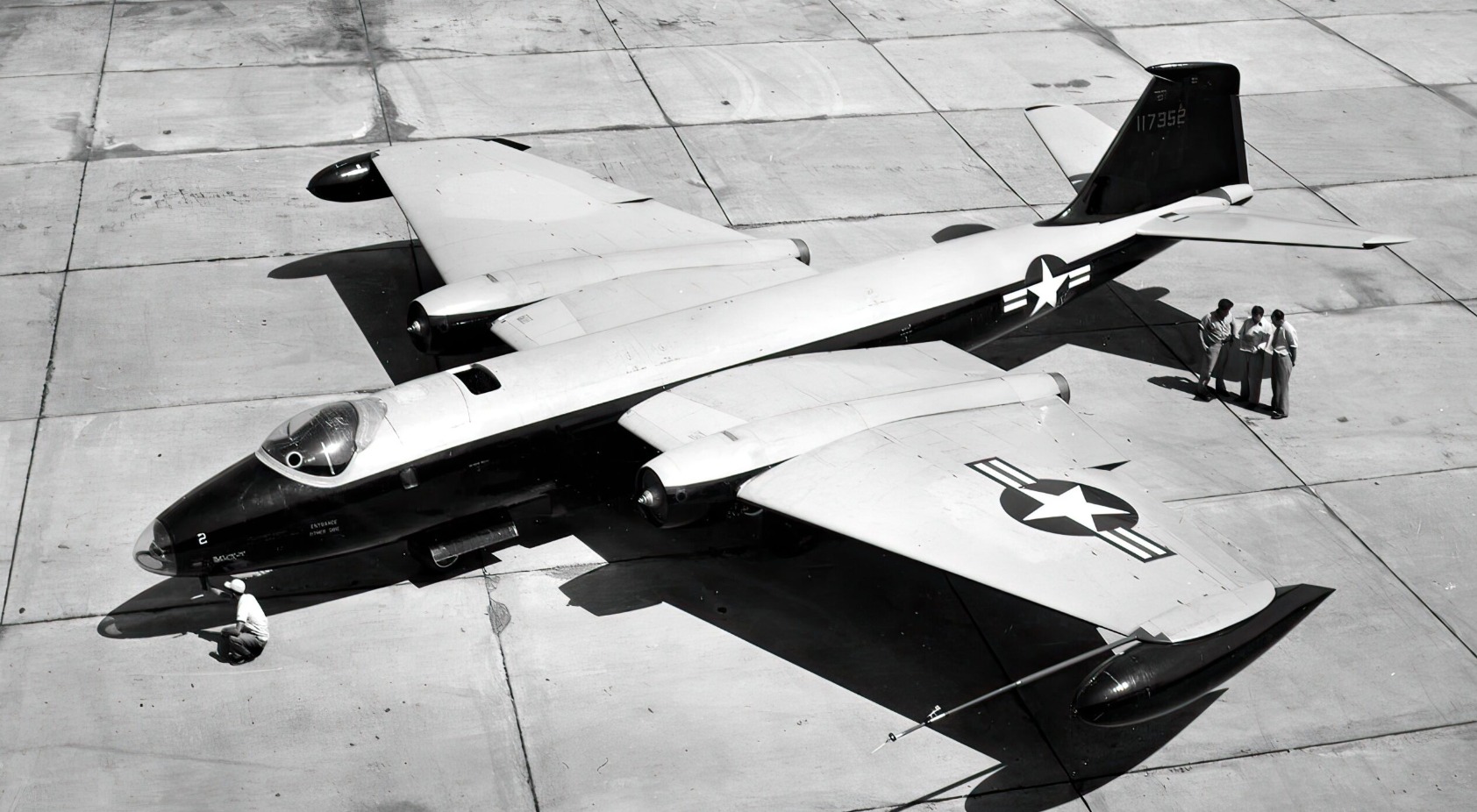

(USAF Photo)

English Electric Canberra: First Generation Jet Bomber. This Canberra is in USAF livery but has the original cockpit. It is likely one of the first built by English Electric and flown to the USA. It was later modified as the Martin B-57.

Martin B-57 Canberrra