RCN and Allied Naval Operations off the coast of Normandy, June 1944

RCN and Allied naval operations off the coast of Normandy in 1944

(DND/PUBLIC ARCHIVES CANADA Photo)

The view from LCI (L) 306 of the 2nd Canadian (262nd RN) Flotilla shows ships of Force J en route to France on D-Day.

Although the Second World War’s Normandy campaign is primarily viewed from the perspective of the related ground fighting, it is also worthwhile to note the extensive naval combat that accompanied the operation. On the eve of the Allied invasion of Normandy, the German Kriegsmarine (navy) possessed 517 surface warships in the Channel area and French Atlantic coast. Large though this force sounded, only a fraction of these vessels (five destroyers, six torpedo boats and 39 E-boats) were suited for offensive action while the rest consisted of various minesweepers, patrol craft and escorts that were mostly conversions from civilian types. Against this, the Allies possessed an invasion fleet consisting of some 7,000 ships and craft including seven battleships, 23 cruisers, 94 fleet destroyers and 143 assorted escort destroyers, frigates and sloops. Despite this disparity, the Kriegsmarine did what it could to counter the Allied onslaught. On the morning of the invasion (6 June 1944) the Germans scored a minor success when a flotilla of torpedo boats and patrol vessels from Le Havre sank the Norwegian-manned destroyer Svenner off Sword Beach for the loss of one of the attending patrol vessels, which was sunk by gunfire from the battleship HMS Warspite.

(Norwegian military museum (Forsvarets Museer) Photo, MMU.941527)

Royal Norwegian Navy destroyer Svenner (G03).

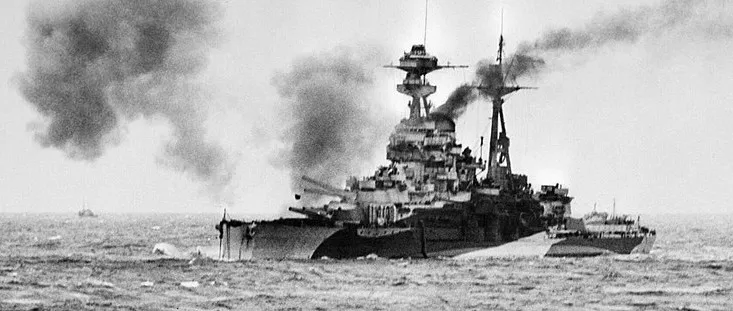

(Royal Navy Photo)

HMS Warspite bombarding the Normandy beaches.

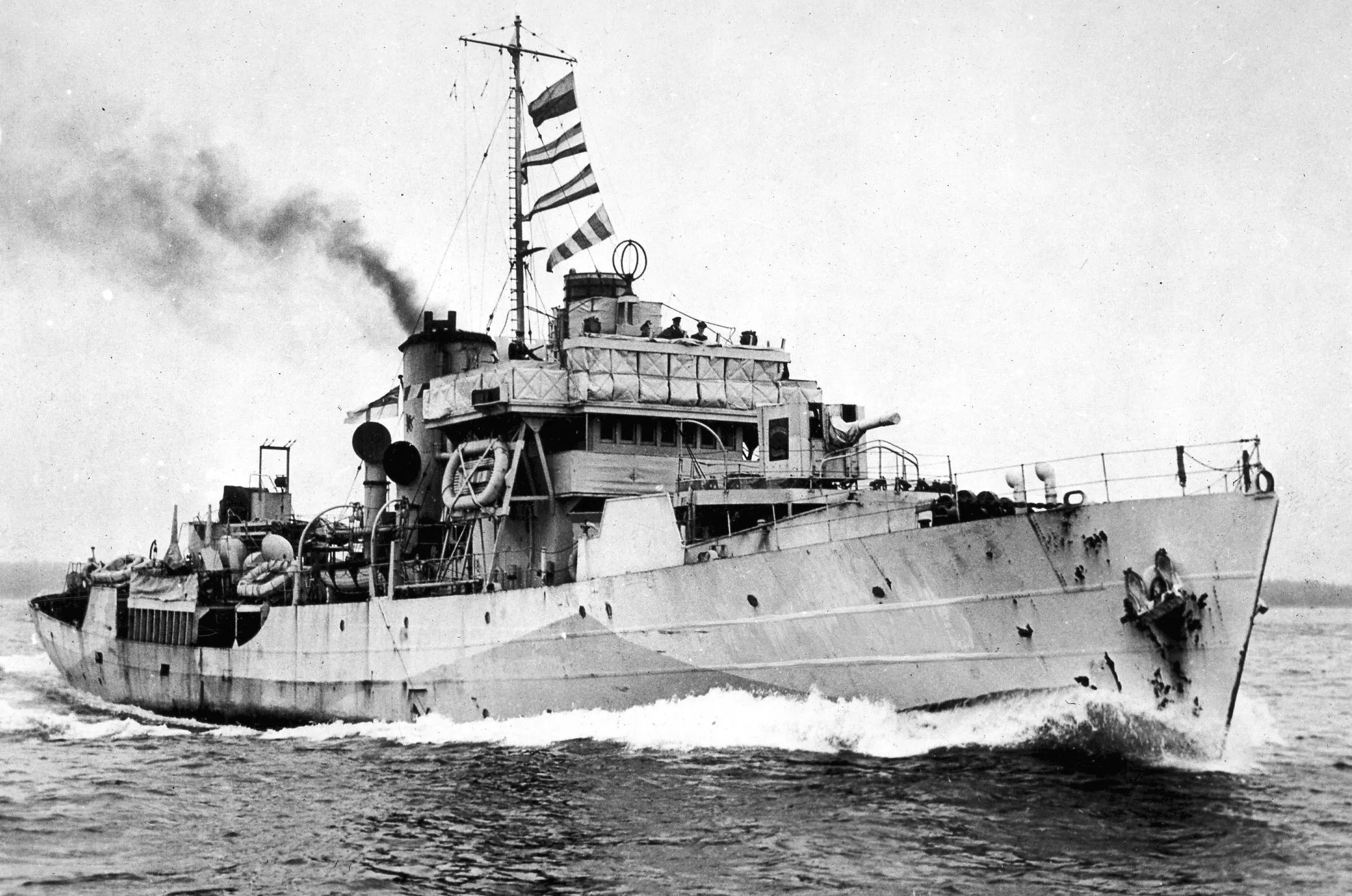

(USN Photo)

The former German destroyer Z39 underway off Boston, Massachusetts, on 22 August 1945. The U.S. Navy designated the destroyer DD-939.

In the days immediately following this event, the German Kriegsmarine attempted to interdict the continuous flow of Allied ships carrying reinforcements and supplies to the landing areas. This included an early effort by three German destroyers (Z32, Z24 and ZH1) and one torpedo boat (T24) to attack the invasion fleet’s western flank. On the night of 8/9 June this force was intercepted and engaged by the British 10th Destroyer Flotilla consisting of four British, two Canadian and two Polish destroyers and under the command of Captain Basil Jones off the Breton coast. In a running fight, these Allied warships destroyed the German destroyers ZH1 and Z32 and drove off the remaining two German warships inflicting heavy damage on Z24 in the process. With this and for no loss to themselves, the British decisively reduced the German destroyer threat from the west, and two months later Z24 and T24 were destroyed by RAF Coastal Command aircraft.

Meanwhile, in the east, German E-boats and occasional torpedo boats sortied out of Cherbourg, Le Havre and Boulogne to conduct minelaying and conventional attacks against the Allied invasion forces on nearly a nightly basis. In the ten days following D-day these German surface craft sank three LSTs, one motor torpedo boat, three coasters, two landing craft and two tugs for the loss of six E-boats. Throughout this process, British Intelligence tracked the movements and whereabouts of these German warships, and on 14 June they determined that most had congregated in Le Havre. That evening 234 Lancaster and Mosquito bombers from RAF Bomber Command attacked Le Havre in three waves. For the loss of one bomber, these aircraft dropped 1,230 tons of bombs on the hapless naval base resulting in the destruction of some 60 assorted vessels including four torpedo boats and 14 E-boats that were either sunk or damaged so severely that they would have to be scuttled. The next night Bomber Command followed this up with a raid against Boulogne that destroyed another 27 German vessels including four fleet minesweepers. The results of these actions effectively eliminated the German surface threat in the English Channel for the remainder of June, and this substantially contributed to the successful Allied build-up in Normandy during this period.

In a future post, I will cover the concurrent U-boat operations that took place in the region during this period. Pictured here are crewman from the British destroyer Tartar displaying the ship’s torn battle ensign following its participation in the action on 8/9 June described above. Hales, G (Sub Lt), Royal Navy official photographer, public Domain. For more information on this and other related topics, see The Longest Campaign, Britain’s Maritime Struggle in the Atlantic and Northwest Europe, 1939-1945. (Brian Walter)

(IWM Photo)

SWORD beach, 6 June 1944. This image is taken from a Royal Air Force Mustang aircraft of II (Army Cooperation) Squadron.

The Royal Canadian Navy and D-Day

By CPO1 (ret’d) Patrick Devenish,

Canadian Naval Memorial Trust

Soldiers, Sailors and Airmen of the Allied Expeditionary Force! You are about to embark on a great crusade, toward which we have striven these many months. The eyes of the world are upon you. The hopes and prayers of liberty loving people everywhere march with you. In company with our brave Allies and brothers in arms on other fronts, you will bring about the destruction of the German war machine, the elimination of Nazi tyranny over the oppressed peoples of Europe, and security for ourselves in a free world. Your task will not be an easy one. Your enemy is well trained, well equipped and battle hardened; he will fight savagely.

But this is the year 1944! Much has happened since the Nazi triumphs of 1940-41. The United Nations have inflicted upon the Germans great defeats, in open battle, man to man. Our air offensive has seriously reduced their strength in the air and their capacity to wage war on the ground. Our home fronts have given us an overwhelming superiority in weapons and munitions of war, and placed at our disposal great reserves of trained fighting men. The tide has turned! The free men of the world are marching together to victory!

I have full confidence in your courage, devotion to duty and skill in battle. We will accept nothing less than full victory. Good Luck! And let us beseech the blessings of Almighty God upon this great and noble undertaking.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower

In his speech to Allied Forces on the eve of D-Day, June 6, 1944, Supreme Allied Commander Europe General Dwight David Eisenhower praised those involved and hinted at the problems to be faced associated with such an undertaking. Conversely (and not widely known), he had prepared a second speech for the next day had the landings been a failure, accepting full responsibility for that failure.

Events like the landings on D-Day do not come together overnight and so it goes without saying that the story of the Royal Canadian Navy’s contributions to that endeavour commenced months before. No story of the RCN’s involvement would be complete without prefacing with the events of one night six weeks prior to the landings.

Operational TUNNEL had three goals: destroy enemy warships in the English Channel, disrupt the enemy’s coastal convoys, and map German strongpoints on the French coast in potential landing areas. As an aside, they also acted as escort for minelayers seeding coastal areas to harass any German shipping. Ships of the Royal Navy’s 10th Flotilla included HMC Ships Haida, Athabaskan and Huron as well as two Polish destroyers, several RN destroyers and the RN cruiser HMS Black Prince. To ensure the success of D-Day, the roughly 230 German surface ships as well as untold numbers of U-boats present in the English Channel needed to be neutralized in the Normandy area. In the five months spanning TUNNEL operations before and after D-Day, the 10th Flotilla alone sank 35 surface vessels and severely damaged 14 more. 10th Flotilla’s sole loss was that of the Tribal class destroyer HMCS Athabaskan along with 128 of her crew in a night action off the Brittany coast, on 29 April 1944.

(DND Photo)

HMCS Athabaskan (G07), ca 1944.

Just prior to the landings, 16 of the RCN’s Bangor class minesweepers as part of the RN’s 14th and the RCN’s 31st and 32nd Flotillas commenced minesweeping operations from their English and Scottish ports and in the hours leading up to the first landings, cleared lanes into several of the anchorage points for the launch of landing craft off the actual invasion beaches at Juno and Omaha.

In the week leading up to the June 5 scheduled landing date (OVERLORD was postponed 24 hours due to bad weather in the Channel), a huge Allied antisubmarine force including 11 Canadian frigates, nine destroyers and five corvettes carried out sweeps in some of the most U-boat infested waters of the Second World War. Nineteen Canadian corvettes were earmarked to escort the huge armada of ships laden with men and equipment destined for one of five landing areas; Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno and Sword. The seaborne portion of Operation OVERLORD was known as Operation NEPTUNE and included just under 7,000 Allied vessels from Infantry Landing Craft and Motor Torpedo Boats to battleships of the Royal and United States Navies and everything in between. The number of Allied sailors involved in the NEPTUNE portion of OVERLORD actually outnumbered the number of troops put ashore on June 6. Canadian Naval Units in the Support and Assault roles included HMC Ships:

Armed Merchant Cruisers (Infantry Landing Ships)

HMCS Prince Henry

HMCS Prince David

Destroyers

HMCS Algonquin

HMCS Sioux

HMCS Haida

HMCS Huron

HMCS Athabaskan*

HMCS Assiniboine

HMCS Chaudiere

HMCS Gatineau

HMCS Kootenay

HMCS Ottawa

HMCS Qu’Appelle

HMCS Saskatchewan

HMCS Skeena*

HMCS St. Laurent

HMCS Restigouche

Minesweepers

HMCS Caraquet

HMCS Canso

HMCS Bayfield

HMCS Blairmore

HMCS Cowichan

HMCS Fort William

HMCS Georgian

HMCS Guysborough*

HMCS Kenora

HMCS Malpeque

HMCS Milltown

HMCS Minas

HMCS Mulgrave

HMCS Thunder

HMCS Vegraville

HMCS Wasaga

Frigates

HMCS Cape Breton

HMCS Grou

HMCS Matane

HMCS New Waterford

HMCS Outremont

HMCS Meon

HMCS Port Colbourne

HMCS Stormont

HMCS St. John

HMCS Swansea

HMCS Teme*

HMCS Waskesiu

Corvettes

HMCS Alberni*

HMCS Baddeck

HMCS Calgary

HMCS Camrose

HMCS Drumheller

HMCS Kitchener

HMCS Lindsay

HMCS Lunenburg

HMCS Mayflower

HMCS Mimico

HMCS Moosejaw

HMCS Rimouski

HMCS Port Arthur

HMCS Prestcott

HMCS Regina*

HMCS Summerside

HMCS Trentonian*

HMCS Woodstock

Other:

29th Motor Torpedo Boat Flotilla*

65th Motor Torpedo Boat Flotilla

528th Landing Craft Assault Flotilla (HMCS Prince Henry)

529th Landing Craft Assault Flotilla (HMCS Prince David)

1st Canadian Landing Craft Infantry Flotilla (ex-RN 260th)

2nd Canadian Landing Craft Infantry Flotilla (ex-RN 262nd)

3rd Canadian Landing Craft Infantry Flotilla (ex-RN 264th)

* Vessels lost either as part of NEPTUNE or in the months following.

On that first day, an Allied Fleet unprecedented in size prior to and since, landed over 90,000 troops, 10,000 vehicles and artillery pieces and over 5,000 tons of food and ammunition. The roughly 10,000 RCN and Canadian Merchant sailors can be justifiably proud of their part in OVERLORD: the beginning of the end for Hitler’s Third Reich.

Seven battleships took part: four Royal Navy and three USN:

_-_80-G-229753.webp)

(USN Photo, 11 April 1944)

USS Arkansas (BB-33), Wyoming-class battleship, eastern Omaha Beach (Wyoming class, 26,100 tons, main armament: twelve 12" guns) primarily in support of the US 29th Infantry Division.

On 18 April, Arkansas departed for Northern Ireland, where she trained for shore bombardment duties, as she had been assigned to the shore bombardment force in support of Operation Overlord, the invasion of northern France. She was assigned to Group II, along with Texas and five destroyers. Her float plane artillery observer pilots were temporarily assigned to VOS-7 flying Spitfires from RNAS Lee-on-Solent (HMS Daedalus). On 3June, she left her moorings, and on the morning of 6 June, took up a position about 4,000 yd (3,700 m) from Omaha Beach. At 05:52, the battleship's guns fired in anger for the first time in her career. She bombarded German positions around Omaha Beach until 13 June, when she was moved to support ground forces in Grandcamp les Bains. On 25 June, Arkansas bombarded Cherbourg, in support ofthe American attack on the port; German coastal guns straddled her several times, but scored no hits. Cherbourg fell to the Allies the next day, after which Arkansas returned to port, first in Weymouth, England, and then to Bangor, Northern Ireland, on 30 June. (Wikipedia)

(USN Photo, 17 September 1944)

USS Nevada (BB-36), Utah Beach (Nevada class, 29,000 tons, main armament: ten 14" guns).

After completion, in mid-1943 Nevada wenton Atlantic convoy duty. Old battleships such as Nevada were attached to manyconvoys across the Atlantic to guard against the chance that a German capitalship might head out to sea on a raiding mission. After completing more convoy runs, Nevada set sail for the United Kingdom toprepare for the Normandy Invasion, arriving in April 1944, with Captain PowellM. Rhea (21 July 1943 – 4 October 1944) in command. Her float plane artilleryobserver pilots were temporarily assigned to VOS-7 flying Spitfires from RNASLee-on-Solent (HMS Daedalus).

She was chosen as Rear Admiral Morton Deyo's flagship for the operation. Duringthe invasion, Nevada supported forces ashore from 6–17 June, and again on 25June; during this time, she employed her guns against shore defenses on theCherbourg Peninsula, "[seeming] to lean back as [she] hurled salvo aftersalvo at the shore batteries." Shells from her guns ranged as far as 17nmi (20 mi; 31 km) inland in attempts to break up German concentrations and counterattacks, even though she was straddled by counterbattery fire 27 times (though never hit).

Nevada was later praised for her "incredibly accurate" fire insupport of beleaguered troops, as some of the targets she hit were just 600 yd(550 m) from the front line. Nevada was the only battleship present at bothPearl Harbor and the Normandy landings.

After D-Day, the Allies headed to Toulon for another amphibious assault,codenamed Operation Dragoon. To support this, many ships were sent from thebeaches of Normandy to the Mediterranean, including five battleships (theUnited States' Nevada, Texas, Arkansas, the British Ramillies, and the FreeFrench Lorraine), three US heavy cruisers (Augusta, Tuscaloosa and Quincy), andmany destroyers and landing craft were transferred south. (Wikipedia)

_fire_on_positions_ashore.webp)

(USN Photo)

Forward 14/45 guns of Nevada fire on positions ashore, during the landings on Utah Beach, 6 June 1944.

(Royal Navy Photo)

HMS Ramillies (1915, Revenge class, 36,125 tons, main armament: eight 15-inch guns).

(IWM Photo, A 23919)

HMS Ramillies bombarding enemy positions on the Normandy Coast on D-Day off Le Havre, France. After her refit in early 1944 to augmenther anti-aircraft defences was completed, HMS Ramillies was assigned to Bombardment Force D, supporting the invasion fleet during the Normandy landings in June. In company with Warspite, the monitor Roberts, five cruisers andfifteen destroyers, the bombardment force operated to the east of Sword Beach,supporting Assault Force S.[65] After assembling in the Clyde area, the forcejoined the main invasion fleet on the morning of 6 June off the French coast. Thetwo battleships opened fire at around 05:30, Ramillies targeting the Germanbattery at Benerville-sur-Mer. Shortly afterwards, three German torpedo boats sortied from Le Havre to attack the bombardment group. Although engaged by both Ramillies and Warspite as well as the cruisers, the German vessels were able toescape after launching fifteen torpedoes at long range. Two torpedoes passedbetween Warspite and Ramillies, and only one vessel, the Norwegian-manneddestroyer Svenner, was struck and sunk.

The battleships resumed shelling the coastal batteries for the rest of the day,suppressing the heavy German guns, which allowed cruisers and destroyers tomove closer in to provide direct fire support to the advancing troops Ramilliescarried out eleven shoots against Bennerville battery with considerableobserved success, to the extent that the battery showed no sign of life in theafternoon. As a result, the planned commando landing to neutralise it(Operations Frog and Deer) were cancelled. The pair of battleships returned totheir station the next day, this time in company with the battleship Rodney.Over the course of the next week, the battleships—with Rodney alternating withher sister Nelson—continually bombarded German defences facing the British andCanadian invasion beaches at Sword, Gold, and Juno. Over the course of herbombardment duties off the Normandy coast, Ramillies fired 1,002 shells fromher main battery. Her worn-out guns had to be replaced afterwards at HMDockyard, Portsmouth. (Wikipedia)

_year_unknown_(50151874546).webp)

(Royal Navy Photo)

HMS Rodney (1925, Nelson-class, 45,500 tons, main armament: nine 16-inch guns).

(IWM Photo, A 23977)

HMS Rodney bombarding gun positions in the Caen area in support of the Normandy landings, June 1944. HMS Rodney was initially in reserve for the Normandy landings (Operation Overlord). HMS Rodney did engage coast-defence guns near Le Havre with two armour-piercing 16-inch shells on 6 June. The ship was ordered forward to support operations off Sword Beach that night and accidentally rammed and sank LCT 427, killing all 13 crewmen, in the darkness and congested waters off the Isle of Wight. Soon afterwards, another LCT rammed HMS Rodney's bow, tearing a9 ft-long (2.7 m) hole in her hull plates and crumpling the bow of the landing craft.

After reaching her assigned position, HMS Rodney engaged targets north of Caen, possibly belonging to the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend which was attacking British and Canadian troops near there. During her day's shooting Rodney expended 99 sixteen- and 132 six-inch shells. That night the ship moved to the waters off Juno Beach to avoid attacks by German light forces. Returning to Sword Beach on 8 June, she bombarded German troops and vehicles near Caen. The following morning Rodney began engaging targets in Caen proper, beginning the gradual devastation of the city, including the destruction of the spire of the Church of Saint-Pierre. That day the ship also fired at coast-defence guns at Houlgate and Benerville-sur-Mer. After an ineffectual air raid on the ships off Sword Beach that afternoon, HMS Rodney withdrew to replenish her ammunition at Milford Haven.

The ship was kept in reserve until 18 June when her sister struck a mine and had to withdraw. A severe storm began the following day and caused all operations to cease. An LCT took shelter in the lee of the battleship for the duration ofthe storm and a trawler collided with Rodney on 21 June but was not seriously damaged. On the night of 23/24 June, the ship was ineffectively attacked twice by Junkers Ju 88 bombers, with her gunners claiming one aircraft shot down. Firing for the first time since her return, HMS Rodney's guns began bombarding targets during Operation Epsom, which began on the 26th. These included a sporadic, 30-hour operation firing an occasional shell 22 miles (35 km) inland, to prevent a Panzer division from crossing a bridge. The ship also provided fire support during Operation Windsor, a partially successful Canadian assault on Carpiquet and its airfield west of Caen on 4 to 5 July, and Operation Charnwood, a frontal assault on Caen proper on 8 to 9 July. Some of the targets engaged were normally beyond the maximum range of HMS Rodney's guns, but oil was pumped to one side to give the ship a temporary list which acted to increase the guns' elevation and range. After the end of Charnwood, the ship was withdrawn as Allied forces drove deeper into France. She had expended a totalof 519 sixteen-inch and 454 six-inch shells during her sojourn off the Normandy coast.

Long-range artillery on the German-occupied island of Alderney was disrupting Allied operations off the north west corner of the Cotentin Peninsula after the landings in Normandy. Rodney was tasked to eliminate the problem and bombarded Batterie Blücher on 12 August, taking up a position on the other side of the Cap de la Hague to avoid return fire. She fired 75 sixteen-inch shells at the artillery position, believing that three of the four guns had been damaged. Postwar analysis showed that although 40 shells had fallen within 200-metres (660 ft) of the centre of the battery, only one gun had actually been damaged, and it was back in service by November. The other three guns resumed shooting at Allied ships by 30 August. (Wikipedia)

(USN Photo, 15 March 1943)

USS Texas (BB-35), western Omaha Beach (New York class, 27,000 tons, main armament: ten 14-inch guns, Flagship of Rear Admiral Carleton F. Bryant) primarily in support of the US 1st Infantry Division. At 03:00 on 6 June 1944, Texas and the British cruiser Glasgow entered the Omaha Western fire support lane and arrived at her initial firing position 12,000 yards (11,000 m) offshore near Pointe du Hoc at 04:41, as part of a combined total US-British flotilla of 702 ships, including seven battleships and five heavy cruisers. The initial bombardment commenced at 05:50, against the site of six 15-centimetre (6 in) guns, atop Pointe du Hoc. When Texas ceased firing at the Pointe at 06:24, 255 14-inch shells had been fired in 34 minutes—an average rate of fire of 7.5 shells per minute, which was the longest sustained period of firing for Texas in the Second World War. While shells from the main guns were hitting Pointe du Hoc, the 5-inch guns were firing on the area leading up to Exit D-1, the route to get inland from western Omaha. At 06:26, Texas shifted her main battery gunfire to the western edge of Omaha Beach, around the town of Vierville. Meanwhile, her secondary battery went to work on another target on the western end of Omaha beach, a ravine laced with strong points to defend an exit road. Later, under control of airborne spotters, she moved her major-caliber fire inland to interdict enemy reinforcement activities and to destroy batteries and other strong points farther inland.

By noon, the assault on Omaha Beach was in danger of collapsing due to stronger than anticipated German resistance and the inability of the Allies to get needed armour and artillery units on the beach. In an effort to help the infantry fighting to take Omaha, some of the destroyers providing gunfire support closed near the shoreline, almost grounding themselves to fire on the Germans. Texas also closed to the shoreline; at 12:23, Texas closed to only 3,000 yd (2,700 m) from the water's edge, firing her main guns with very little elevation to clear the western exit D-1, in front of Vierville. Among other things, she fired upon snipers and machine gun nests hidden in a defile just off the beach. At the conclusion of that mission, the battleship attacked an enemy anti-aircraft battery located west of Vierville.

On 7 June, the battleship received word that the Ranger battalion at Pointe Du Hoc was still isolated from the rest of the invasion force with low ammunition and mounting casualties; in response, Texas obtained and filled two LCVPs with provisions and ammunition for the Rangers. Upon their return, the LCVPs brought thirty-five wounded Rangers to Texas for treatment of whom one died on the operating table. Along with the Rangers, a deceased Coast Guardsman and twenty-seven prisoners (twenty Germans, four Italians, and three French) were brought to the ship. The prisoners were fed, segregated, and not formally interrogated aboard Texas, due to the ship bombarding targets or standing by to bombard, before being loaded aboard an LST for transfer to England. Later in the day, her main battery rained shells on the enemy-held towns of Formigny and Trévières to break up German troop concentrations. That evening, she bombarded a German mortar battery that had been shelling the beach. Not long after midnight, German planes attacked the ships offshore, and one of them swooped in low on Texas's starboard quarter. Her anti-aircraft batteries opened up immediately but failed to hit the intruder. On the morning of 8 June, her guns fired on Isigny, then on a shore battery, and finally on Trévières once more.

After that, she retired to Plymouth to rearm, returning to the French coast on 11 June. From then until June 15, she supported the army in its advance inland. By 15 June, the troops had advanced to the edge of Texas's gun range; her last fire support mission was so far inland that to get the needed range, the starboard torpedo blister was flooded with water to provide a list of two degrees which gave the guns enough elevation to complete the fire mission. With combat operations beyond the range of her guns on 16 June, Texas left Normandy for England on 18 June. (Wikipedia)

(IWM Photo, A 117870

HMS Warspite (1913, Queen Elizabeth class, 38,700 tons, main armament eight 15-inch guns, only six operational).

She left Greenock on 2 June 1944 with six15-inch guns, eight 4-inch anti-aircraft guns and forty pom poms, joining Bombardment Force D of the Eastern Task Force of the Normandy invasion fleetoff Plymouth two days later.

At 0500 on 6 June 1944, Warspite was the first ship to open fire, bombarding the German battery at Villerville from a position 26,000 yards offshore, to support landings by the British 3rd Division on Sword Beach. She continued bombardment duties on 7 June, but after firing over 300 shells she had to rearm and crossed the Channel to Portsmouth. She returned to Normandy on 9 June to support American forces at Utah Beach and then, on 11 June, she took upposition off Gold Beach to support the British 69th Infantry Brigade near Cristot. On 12 June, she returned to Portsmouth to rearm, but her guns were worn out so she was ordered to sail to Rosyth via the Straits of Dover, the first British battleship to have done so since the war began. She evaded German coastal batteries, partly due to effective radar jamming, but hit a mine 28 miles off Harwich early on 13 June. Repairs to her propeller shafts and the replacement of the guns took until early August; she sailed to Scapa Flow to calibrate the new barrels with only three functional shafts, limiting her top speed to 15 knots, although by now the Admiralty considered her main role was that of a bombardment vessel.

Warspite arrived off Ushant on 25 August 1944 and attacked the coastal batteries at Le Conquet and Pointe Saint-Mathieu during the Battle for Brest.The U.S. VIII Corps eventually captured "Festung Brest" on 19 September, but by then Warspite had moved on to the next port. In company withthe monitor Erebus, she carried out a preparatory bombardment of targets around Le Havre prior to Operation Astonia on 10 September, leading to the capture of the town two days later. Her final task was to support an Anglo-Canadian operation to open up the port of Antwerp, which had been captured in September, by clearing the Scheldt Estuary of German strongholds and gun emplacements. With the monitors Erebus and Roberts, she bombarded targets on Walcheren Island on 1 November 1944, returning to Deal the next day, having fired her guns for the last time. (Wikipedia)

In addition HMS Nelson (Nelson class main armament: nine 16-inch guns) was held in reserve until June 10.

Five heavy cruisers (main guns of 8 inches) took part, three from the United States and two from Britain:

HMS Hawkins had her original armament of seven 7.5-inch guns while HMS Frobisher's main gun armament had been reduced from seven to five single-mounted 7.5-inch guns. USS Augusta (Flagship of Rear Admiral Alan Kirk – Lt. General Omar Bradley embarked).

HMS Frobisher.

HMS Hawkins.

USS Quincy.

USS Tuscaloosa.

17 British light cruisers took part along with two of the Free French navy, and one of the Polish navy. All carried either 6-inch or 5.25-inch guns of varying numbers:

HMS Argonaut, HMS Ajax, HMS Arethusa, HMS Belfast (Flagship of Rear Admiral Frederick Dalrymple-Hamilton), HMS Bellona - also carried jamming equipment against radio controlled bombs, HMS Black Prince, HMS Capetown, HMS Ceres (Flagship of U.S. Service Force), HMS Danae, HMS Diadem, ORP Dragon (Polish, damaged in July and then used as a blockship in "Gooseberry" breakwater), HMS Emerald, HMS Enterprise, Georges Leygues (Free French), HMS Glasgow, HMS Mauritius (Flagship of Rear Admiral Patterson), Montcalm (Free French, Flagship of Rear Admiral Jaujard), HMS Orion (which fired the first shell of the coastal bombardment), HMS Scylla (Rear Admiral Philip Vian's flagship, mined and seriously damaged, out of action until after the war), HMS Sirius In reserve until June 10.

139 destroyers and escort ships (eighty-five British and Dominion, 40 US, 10 Free French and 7 other Allied), including RCN HMCS Alberni, HMCS Algonquin, and HMCS Kitchener.

(DND Photo)

HMCS Alberni (K103) (Flower-class Corvette).

(DND Photo)

HMCS Algonquin (R17).

(RCN Photo)

HMCS Kitchener (K225) (Flower-class Corvette).

Monitors: HMS Erebus, monitor with two 15-inch gunsHMS Roberts, monitor with two 15-inch guns.

Troop Transports: USS Joseph T. Dickman, attack transport, USS Samuel Chase, attack transport operated by the US Coast Guard, USS Charles Carroll, attack transport, USS Bayfield, attack transport, USS Henrico, attack transport.

508 other warships (352 British, 154 US and 2 other Allied), including the minesweeper HMCS Cowichan.

(DND Photo)

HMCS Cowichan (J146) (Bangor-class).

D-Day Support ships

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 4233774)

British Everard cased petrol carrier MV Signality, off the French coast on 6 June 1944.

British Everard cargo vessel SIGNALITY 487/37 provided support for the Allied forces going ashore during the Normandy landings. After loading her cargo, she left London from the King George V dock on 19 May 1944. On 31 May she sailed down the Thames River to her staging base in the Solen Anchorage 3N/e9. The Signality arrived off Juno beach on 6 June in a follow-up Convoy and discharged her cargo of cased petrol and stores between 2100 hrs on the 6th and 1500 hrs on the 7th. She then returned to London, Purfeet B.

The Everard cased petrol carrier MV Signality and her sister ship MV Sedulity joined a group of 33 coasters deployed in the Solent. In addition to their cargo of fuel, they had loaded Royal Engineer equipment and Bailey bridging. They were part of a fleet of at least 128 coasters which had been waiting in the 20-mile stretch of the Thames between Blackwall and Tilbury. They were among more than 500 ships in a vast anchorage, extending from Hurst Castle in the west to Benbridge in the east, in which every suitable space had been allocated for vessels assembling in the run-up to D-Day.

Although these ships were initially directed to sail directly to the French coast on 5 June, bad weather caused a 24-hour delay.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 423377)

British Everard cased petrol carrier MV Signality, with DUKWs alongside, off the French coast on 6 June 1944.

(Everard Photo)

British Everard cased petrol carrier MV Signality, post-war.