Warships of the US Navy: aircraft carriers: USS Langley (CV-1), USS Lexington (CV-2), USS Saratoga (CV-3), USS Ranger (CV-4), USS Yorktown (CV-5), USS Enterprise (CV-6), USS Wasp (CV-7), USS Hornet (CV-8)

USN Aircraft Carriers: Lexington-class, Ranger-class, Yorktown-class, and Wasp-class in the Second Word War

Between 1941 and 1945, the United States Navy commissioned several classes of aircraft carriers, namely the Lexington, Ranger, Wasp, Yorktown, and Essex classes, which became instrumental in establishing air and naval superiority. USS Langley (CV-1), USS Lexington (CV-2), USS Saratoga (CV-3), USS Ranger (CV-4), USS Yorktown (CV-5), USS Enterprise (CV-6), USS Wasp (CV-7), USS Hornet (CV-8). (Essex class aircraft carriers are listed on a separate page on this website).

USS Langley (CV-1/AV-3)

USS Langley (CV-1/AV-3) was the United States Navy's first aircraft carrier, converted in 1920 from the collier USS Jupiter (Navy Fleet Collier No. 3), and also the US Navy's first turbo-electric-powered ship. Langley was named after Samuel Langley, an American aviation pioneer. She was the sole member of her class to be rebuilt as a carrier. Conversion of another collier was planned but canceled when the Washington Naval Treaty required the cancellation of the partially built Lexington-class battlecruisers Lexington and Saratoga, freeing up their hulls for conversion to the aircraft carriers Lexington and Saratoga. Following another conversion to a seaplane tender, Langley saw service in the Second World War. On 27 February 1942, while ferrying a cargo of USAAF P-40s to Java, she was attacked by nine twin-engine Japanese bombers of the Japanese 21st and 23rd naval air flotillas and so badly damaged that she had to be scuttled by her escorts. (Wikipedia)

.webp)

(USN Photo)

USS Langley (CV 1) going by the oil docks at Pearl Harbor, Territory of Hawaii, 4 May 1925.

_underway_in_June_1927_(cropped).webp)

(USN Photo)

USS Langley (CV-1) underway in June 1927.

Lexington-class

The Lexington-class aircraft carriers were a pair of aircraft carriers built for the United States Navy (USN) during the 1920s, the USS Lexington (CV-2) and USS Saratoga (CV-3). The ships were built on hulls originally laid down as battlecruisers after World War I, but under the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922, all U.S. battleship and battlecruiser construction was cancelled. The Treaty, however, allowed two of the unfinished ships to be converted to carriers. They were the first operational aircraft carriers in the USN[N 1] and were used to develop carrier aviation tactics and procedures before the Second World War in a series of annual exercises.They proved extremely successful as carriers and experience with the Lexington class convinced the Navy of the value of large carriers. They were the largest aircraft carriers in the USN until the Midway-class aircraft carriers were completed beginning in 1945. The ships served in the Second World War, seeing action in many battles. Although Lexington was sunk in the first carrier battle in history (the Battle of the Coral Sea) in 1942, Saratoga served throughout the war, despite being torpedoed twice, notably participating in the Battle of the Eastern Solomons in mid-1942 where her aircraft sank the Japanese light carrier Ryūjō. She supported Allied operations in the Indian Ocean and South West Pacific Areas until she became a training ship at the end of 1944. Saratoga returned to combat to protect American forces during the Battle of Iwo Jima in early 1945, but was badly damaged by kamikazes. The continued growth in the size and weight of carrier aircraft made her obsolete by the end of the war. In mid-1946, the ship was purposefully sunk during nuclear weapon tests in Operation Crossroads. (Wikipedia)

USS Lexington (CV-2)

USS Lexington (CV-2). Commissioned 14 Dec 1927. She was the first of two carriers in the Second World War to be named Lexington. Lexington was one of the few carriers to be commissioned well before the war started. During the attack on Pearl Harbor, Lexington was en route to Midway Island, delivering aircraft. It later engaged in diversionary attacks in the Marshall Islands. Alongside USS Yorktown, it fought in the Battle of the Coral Sea. After enduring torpedo and aerial bomb hits, Lexington was scuttled, marking the first loss of an American aircraft carrier in the war. (USN)

_leaving_San_Diego_on_14_October_1941_(80-G-416362).webp)

(USN Photo)

USS Lexington (CV-2) leaving San Diego, California (USA), on 14 October 1941. Planes parked on her flight deck include Brewster F2A-1 fighters (parked forward), Douglas SBD scout-bombers (amidships) and Douglas TBD-1 torpedo planes (aft). Note the false bow wave painted on her hull, forward, and badly chalked condition of the hull's camouflage paint.

_with_tugs_in_January_1928.webp)

(USN Photo)

Commercial tugboats assist the U.S. Navy aircraft carrier USS Lexington (CV-2) during her transit from the Fore River Shipyard in Quincy, Massachusetts (USA), to the Boston Navy Yard for her final dry docking before her shakedown cruise.

(USN Photo)

The forward starboard 8" (203mm) and 5" (127mm) guns of USS Lexington (CV-2). Lexington originally only carried eight 8" (split forward and aft in twin turrets) and twelve 5" guns as her armament (three single mounts to each quadrant of the flightdeck).

_burning_and_sinking_on_8_May_1942_(NH_51382).webp)

(USN Photo)

USS Lexington (CV-2), burning and sinking after her crew abandoned ship during the Battle of the Coral Sea, 8 May 1942. Note the planes parked aft, where the fires have not yet reached.

(USN Photo)

Crewmen abandon ship on board the U.S. aircraft carrier USS Lexington (CV-2) after the carrier was hit by Japanese torpedoes and bombs during the Battle of the Coral Sea, on 8 May 1942. Note the destroyer alongside taking on survivors.

Battle of the Coral Sea

The Japanese and American forces needed to refuel, but TF 17 finished first, and Fletcher tookYorktown and her consorts northward toward the Solomon Islands on 2 May. TF 11 was ordered to rendezvous with TF 17 and Task Force 44, the former ANZAC Squadron, further west into the Coral Sea on 4 May. The Japanese opened Operation Mo by occupying Tulagi on 3 May. Alerted by Allied reconnaissance aircraft, Fletcher decided to attack Japanese shipping there the following day. The air strike on Tulagi confirmed that at least one American carrier was in the vicinity, but the Japanese had no idea of its location. They launched reconnaissance aircraft the following day to search for the Americans, but without result. One H6K flying boat spotted Yorktown but was shot down by one of Yorktown's Wildcat fighters before she could radio a report. US Army Air Forces (USAAF) aircraft spotted Shōhō southwest of Bougainville Island on 5 May, but she was too far north to be attacked by the American carriers, which were refueling. That day, Fletcher received Ultra intelligence that placed the three Japanese carriers known to be involved in Operation Mo near Bougainville Island, and predicted 10 May as the date of the invasion. It also predicted airstrikes by the Japanese carriers in support of the invasion several days before 10 May. Based on this information, Fletcher planned to complete refueling on 6 May and to move closer to the eastern tip of New Guinea to be in a position to locate and attack Japanese forces on 7 May.

Another H6K spotted the Americans during the morning of 6 May and successfully shadowed them until 1400. The Japanese, however, were unwilling or unable to launch air strikes in poor weather or without updated spot reports. Both sides believed they knew where the other force was and expected to fight the next day. The Japanese were the first to spot their opponents when one aircraft found the oiler Neosho escorted by the destroyer Sims at 0722, south of the strike force. They were misidentified as a carrier and a cruiser so the fleet carriers Shōkaku and Zuikaku launched an airstrike 40 minutes later that sank Sims and damaged Neosho badly enough that she had to be scuttled a few days later. The American carriers were west of the Japanese carriers, not south, and they were spotted by other Japanese aircraft shortly after the carriers had launched their attack on Neosho and Sims.

American reconnaissance aircraft reported two Japanese heavy cruisers northeast of Misima Island in the Louisiade Archipelago off the eastern tip of New Guinea at 07:35 and two carriers at 08:15. An hour later Fletcher ordered an airstrike launched, believing that the two carriers reported were Shōkaku and Zuikaku. Lexington and Yorktown launched a total of 53 Dauntlesses and 22 Devastators escorted by 18 Wildcats. The 08:15 report turned out to be miscoded, as the pilot had intended to report two heavy cruisers, but USAAF aircraft had spotted Shōhō, her escorts and the invasion convoy in the meantime. As the latest spot report plotted only 30 nautical miles (56 km; 35 mi) away from the 08:15 report, the aircraft en route were diverted to this new target.

Shōhō and the rest of the main force were spotted by aircraft from Lexington at 10:40. At this time, Shōhō's patrolling fighters consisted of two Mitsubishi A5M "Claudes" and one Mitsubishi A6M Zero. The dive bombers of VS-2 began their attack at 1110 as the three Japanese fighters attacked the Dauntlesses in their dive. None of the dive bombers hit Shōhō, which was maneuvering to avoid their bombs; one Zero shot down a Dauntless after it had pulled out of its dive; several other Dauntlesses were also damaged. The carrier launched three more Zeros immediately after this attack to reinforce its defenses. The Dauntlesses of VB-2 began their attack at 11:18 and they hit Shōhō twice with 1,000-pound (450 kg) bombs. These penetrated the ship's flightdeck and burst inside her hangars, setting the fueled and armed aircraft there on fire. A minute later the Devastators of VT-2 began dropping their torpedoes from both sides of the ship. They hit Shōhō five times and the damage from the hits knocked out her steering and power. In addition, the hits flooded both the engine and boiler rooms. Yorktown's aircraft finished the carrier off and she sank at 11:31. After his attack, Lieutenant Commander Robert E. Dixon, commander of VS-2, radioed his famous message to the American carriers: "Scratch one flat top!"

After Shōkaku and Zuikaku had recovered the aircraft that had sunk Neosho and Sims, Rear Admiral Chūichi Hara, commander of the 5th Carrier Division, ordered that a further air strike be readied as the American carriers were believed to have been located. The two carriers launched a total of 12 Aichi D3A "Val" dive bombers and 15 Nakajima B5N "Kate" torpedo bombers late that afternoon. The Japanese had mistaken Task Force 44 for Lexington and Yorktown, which were much closer than anticipated, although they were along the same bearing. Lexington's radar spotted one group of nine B5Ns at 17:47 and half the airborne fighters were directed to intercept them while additional Wildcats were launched to reinforce the defences. The intercepting fighters surprised the Japanese bombers and shot down five while losing one of their own. One section of the newly launched fighters spotted the remaining group of six B5Ns, shooting down two and badly damaging another bomber, although one Wildcat was lost to unknown causes. Another section spotted and shot down a single D3A. The surviving Japanese leaders canceled the attack after such heavy losses and all aircraft jettisoned their bombs and torpedoes. They had still not spotted the American carriers and turned for their own ships, using radio direction finders to track the carrier's homing beacon. The beacon broadcast on a frequency very close to that of the American ships and many of the Japanese aircraft confused the ships in the darkness. A number of them flew right beside the American ships, flashing signal lights in an effort to confirm their identity, but they were not initially recognized as Japanese because the remaining Wildcats were attempting to land aboard the carriers. Finally, they were recognized and fired upon, by both the Wildcats and the anti-aircraft guns of the task force, but they sustained no losses in the confused action. One Wildcat lost radio contact and could not find either of the American carriers; the pilot was never found. The remaining 18 Japanese aircraft successfully returned to their carriers, beginning at 20:00.

8 May 1942

On the morning of 8 May, both sides spotted each other about the same time and began launching their aircraft about 09:00. The Japanese carriers launched a total of 18 Zeros, 33 D3As and 18 B5Ns. Yorktown was the first American carrier to launch her aircraft, and Lexington began launching hers seven minutes later. These totaled 9 Wildcats, 15 Dauntlesses and 12 Devastators. Yorktown's dive bombers disabled Shōkaku's flight deck with two hits and Lexington's aircraft were only able to further damage her with another bomb hit. None of the torpedo bombers from either carrier hit anything. The Japanese CAP was effective and shot down 3 Wildcats and 2 Dauntlesses for the loss of 2 Zeros.

The Japanese aircraft spotted the American carriers around 11:05 and the B5Ns attacked first because the D3As had to circle around to approach the carriers from upwind. American aircraft shot down four of the torpedo bombers before they could drop their torpedoes, but 10 survived long enough to hit Lexington twice on the port side at 11:20, although 4 of the B5Ns were shot down by anti-aircraft fire after dropping their torpedoes. War correspondent Stanley Johnston, who was on the signal bridge during the battle, noted five torpedo hits on the port side from 11:18 to11:22. The shock from the first torpedo hit at the bow jammed both elevators in the up position and started small leaks in the port avgas storage tanks. The second torpedo hit her opposite the bridge, ruptured the primary port watermain, and started flooding in three port fire rooms. The boilers there had to be shut down, which reduced her speed to a maximum of 24.5 knots (45.4 km/h;28.2 mph), and the flooding gave her a 6–7° list to port. Shortly afterward, Lexington was attacked by 19 D3As. One was shot down by fighters before it could drop its bomb and another was shot down by the carrier. She was hit by two bombs, the first of which detonated in the port forward five-inch ready ammunition locker, killing the entire crew of one five-inch gun and starting several fires. The second hit struck the funnel, doing little significant damage although fragments killed many of the crews of the .50-caliber machineguns positioned near there. The hit also jammed the ship's siren in the "on" position. The remaining bombs detonated close alongside and some of their fragments pierced the hull, flooding two compartments.

Fuel was pumped from the port storage tanks to the starboard side to correct the list and Lexington began recovering damaged aircraft and those that were low on fuel at 11:39. The Japanese had shot down three of Lexington's Wildcats and five Dauntlesses, plus another Dauntless crashed on landing. At 12:43, the ship launched five Wildcats to replace the CAP and prepared to launch another nine Dauntlesses. A massive explosion at 12:47 was triggered by sparks that ignited gasoline vapours from the cracked port avgas tanks. The explosion killed 25 crewmen and knocked out the main damage control station. The damage did not interfere with flight deck operations, although the refueling system was shutdown. The fueled Dauntlesses were launched and six Wildcats that were low on fuel landed aboard. Aircraft from the morning's air strike began landing at 13:22 and all surviving aircraft had landed by 14:14. The final tally included three Wildcats that were shot down, plus one Wildcat, three Dauntlesses and one Devastator that were forced to ditch.

Another serious explosion occurred at 14:42 that started severe fires in the hangar and blew the forward elevator 12 inches (305 mm) above the flight deck. Power to the forward half of the ship failed shortly afterward. Fletcher sent three destroyers to assist, but another major explosion at 15:25 knocked out water pressure in the hangar and forced the evacuation of the forward machinery spaces. The fire eventually forced the evacuation of all compartments below the waterline at 16:00 and Lexington eventually drifted to a halt. Evacuation of the wounded began shortly afterward, and Sherman ordered "abandonship" at 17:07. A series of large explosions began around 18:00 that blew the aft elevator apart and threw aircraft into the air. Sherman waited until 18:30 to ensure that all of his crewmen were off the ship before leaving himself. Some 2,770 officers and men were rescued by the rest of the task force. The destroyer Phelps was ordered to sink the ship and fired a total of five torpedoes between 19:15 and 19:52. Immediately after the last torpedo hit, Lexington finally slipped beneath the waves at 15°20′S 155°30′E. Some 216 crewmen were killed and 2,735 were evacuated. 17 SBD Dauntless dive bombers, 13 F4F Wildcat fighters, and 12 TBD Devastator torpedo bombers, 42 planes total, went down with Lexington. (Wikipedia)

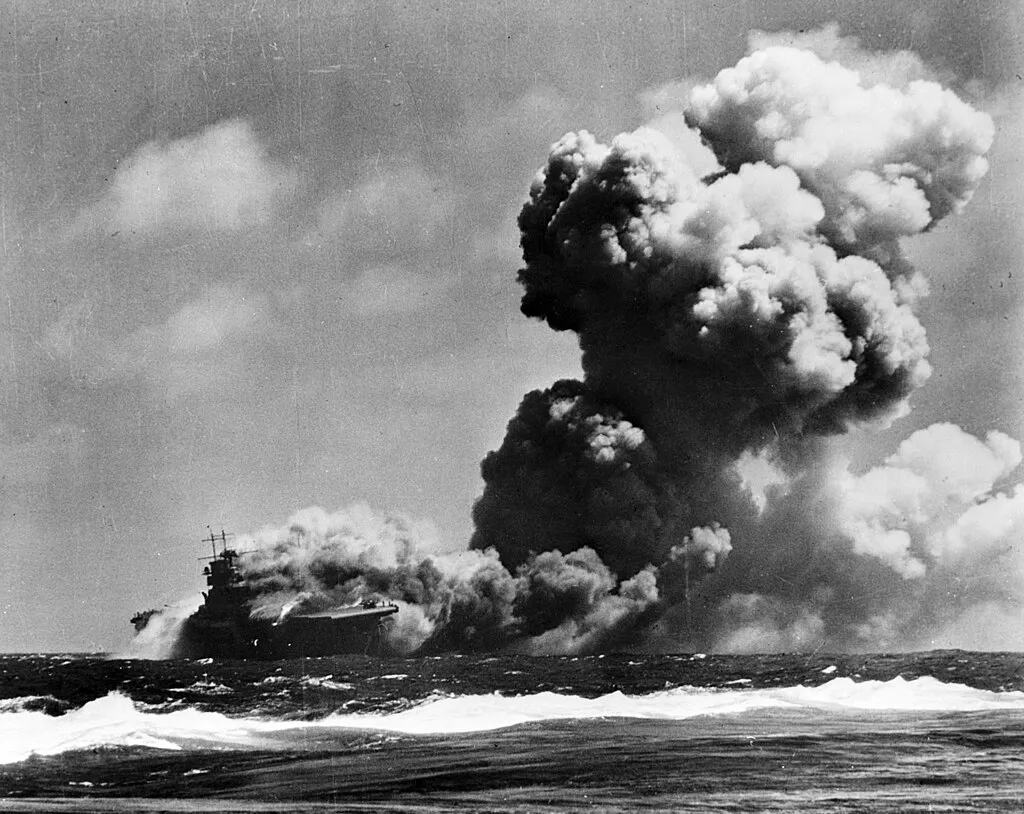

%2C_8_May_1942_(80-G-16651).webp)

(USN Photo)

A mushroom cloud rises after a heavy explosion on board the U.S. Navy aircraft carrier USS Lexington (CV-2), 8 May 1942. This is probably the great explosion from the detonation of torpedo warheads stowed in the starboard side of the hangar, aft, that followed an explosion amidships at 1727 hrs. Note USS Yorktown (CV-5) on the horizon in the left center, and destroyer USS Hammann (DD-412) at the extreme left.

USS Saratoga (CV-3)

USS Saratoga (CV-3). Commissioned 16 Nov 1927. She was built in 1927, initially as a battle cruiser but later completed as an aircraft carrier, and she served as the U.S. Navy’s first fast carrier. Saratoga played a key role in the Guadalcanal campaign, sinking the Japanese carrier Ryujo and providing air cover for the landings. Saratoga survived torpedo hits and continued operations until the end of the war. After the war, the ship was destroyed in atomic bomb testing at Bikini Atoll.

_underway%2C_May_1945.webp)

(USN Photo)

USS Saratoga (CV-3) running full power trials in Puget Sound, Washington (USA), following battle damage repairs, 15 May 1945.

_underway%2C_circa_in_1942_(80-G-K-459).webp)

(USN Photo)

USS Saratoga (CV-3), circa 1942. Planes on deck include five Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat fighters, six Douglas SBD-3 Dauntless dive bombers and one Grumman TBF-1 Avenger torpedo plane.

_underway_in_Puget_Sound_on_7_September_1944_(19-N-72626).webp)

(USN Photo)

USS Saratoga (CV-3) underway in Puget Sound, Washington (USA), making 12 knots, 7 September 1944. Saratoga wears her single Camouflage Measure 32 Design 11A.

(USN Photo)

The U.S. Navy aircraft carrier USS Saratoga (CV-3) under repair at Tongatabu, Tonga Islands, in September 1942. She had been torpedoed by the Japanese submarine I-26 on 31 August. The torpedo struck Saratoga on her starboard side, just aft of the island. The torpedo wounded a dozen of her sailors, including Vice Admiral Fletcher, and it flooded one fireroom, giving the ship a 4° list, but it caused multiple electrical short circuits. These damaged Saratoga's turbo-electric propulsion system and left her dead in the water for a time. The heavy cruiser USS Minneapolis (CA-36) took Saratoga in tow while she launched her aircraft for Espiritu Santo, retaining 36 fighters aboard. By noon, the list had been corrected and she was able to steam under her own power later that afternoon.Note: The list seen in this photo is probably deliberate, to bring the damaged part of Saratoga's hull out of water as she had been hit on the starboard side, amidships.

.webp)

(USN Photo)

Aerial view from a U.S. Navy Martin PBM Mariner (callsign "U") of the Crossroads Baker atomic test, less than one second after the detonation. Identifiable ships are (l-r): USS Pensacola (CA-24), USS Saratoga (CV-3), USS Pennsylvania (BB-38), the former Japanese battleship Nagato, USS New York (BB-34), and USS Salt Lake City (CA-25).

Ranger-class

USS Ranger (CV-4) was an interwar United States Navy aircraft carrier, the only ship of its class. As a Treaty ship, Ranger was the first U.S. vessel to be designed and built from the keel up as a carrier. She was relatively small, just 730 ft (222.5 m) long and under 15,000 long tons (15,000 t), closer in size and displacement to the first US carrier—Langley—than later ships. An island superstructure was not included in the original design, but was added after completion. Deemed too slow for use with the Pacific Fleet's carrier task forces against Japan, she spent most of the Second World War in the Atlantic Ocean, where the German fleet, the Kriegsmarine, was a weaker opponent. Ranger saw combat in that theater and provided air support for Operation Torch. In October 1943, she fought in Operation Leader, air attacks on German shipping off Norway. She was sold for scrap in 1947. (Wikipedia)

USS Ranger (CV-4)

USS Ranger (CV-4). Commissioned 4 Jun 1934. Sher was the first US aircraft carrier to be built as such, rather than being repurposed from an existing ship hull. During the war, Ranger mostly fulfilled escort carrier duties. Lacking the speed and capacity of larger carriers, Ranger served in convoy escort, aircraft transport, and amphibious support roles. It survived the war along with two other pre-war carriers, USS Enterprise and USS Saratoga. After the war, it underwent overhaul and was ultimately decommissioned in 1946 before being sold for scrapping in 1947.

_anchored_in_Guantanamo_Bay_on_10_November_1939.webp)

(USN Photo)

USS Ranger (CV-4) anchored in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, on 10 November 1939.

_in_Panama_Canal_1945.webp)

(USN Photo)

USS Ranger (CV-4) transits through the Panama Canal in 1945.

Yorktown-class

The Yorktown class was a class of three aircraft carriers built for the United States Navy and completed shortly before the Second World War, the USS Yorktown (CV-5), USS Enterprise (CV-6), and USS Hornet (CV-8). They immediately followed USS Ranger (CV-2), the first U.S. aircraft carrier built as such, and benefited in design from experience with Ranger and the earlier Lexington class, which were conversions into carriers of two battlecruisers that were to be scrapped to comply with the Washington Naval Treaty, an arms limitation accord. These ships bore the brunt of the fighting in the Pacific during 1942, and two of the three were lost: Yorktown, sunk at the Battle of Midway, and Hornet, sunk in the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands. Enterprise, the sole survivor of the class, was the most decorated ship of the U.S. Navy in the Second World War. After efforts to save her as a museum ship failed, she was scrapped in 1958. (Wikipedia)

USS Yorktown (CV-5)

USS Yorktown (CV-5). Commissioned 30 Sep 1937. Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Yorktown passed through the Panama Canal to reinforce the Pacific Fleet. Despite damage sustained during the battle of the Coral Sea, Yorktown participated in the Battle of Midway, contributing to the sinking of Japanese carriers. Eventually, she was sunk by the Japanese submarine I-168. The wreck was discovered in 1998.

_Jul1937.webp)

(USN Photo)

USS Yorktown (CV-5) underway, on 21 July 1937.

_anchored_in_Hampton_Roads_on_30_October_1937.webp)

(USN Photo)

USS Yorktown (CV-5) anchored in Hampton Roads, Virginia, on 30 October 1937.

.webp)

(USN Photo)

USS Yorktown (CV-5) in Dry Dock No. 1 at the Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard, 29 May 1942, receiving urgent repairs for damage received in the Battle of Coral Sea. She left Pearl Harbor the next day to participate in the Battle of Midway. USS West Virginia (BB-48), sunk in the 7 December 1941 Japanese air attack, is being salvaged in the left distance.

_underway_at_Midway_1942.webp)

(USN Photo)

USS Yorktown (CV-5) underway with her air group on the flight deck, 4 June 1942, probably about 0630-0730 hrs, following recovery of her morning search and respotting the flight deck with her strike group. Several Douglas SBD Dauntless scout bombers are on deck alongside and forward of the island, with many other planes densely parked aft. Douglas TBD-1 Devastator torpedo bombers are at the flight deck's rear.

(USN Photo)

USS Yorktown (CV-5) burning after the first attack by Japanese dive bombers during the Battle of Midway on 4 June 1942

Battle of Midway

U.S. naval intelligence had gained enough information from decoded Japanesenaval messages to estimate that the Japanese were on the threshold of a majoroperation aimed at the northwestern tip of the Hawaiian chain. These were twoislets in a low coral atoll known as Midway Island. Armed with thisintelligence, Admiral Nimitz began methodically planning Midway's defense,rushing all possible reinforcement in the way of men, planes and guns toMidway. In addition, he began gathering his comparatively meager naval forcesto meet the enemy at sea. As part of those preparations, he recalled TF 16,Enterprise and Hornet to Pearl Harbor for a quick replenishment.

Yorktown, too, received orders to return to Hawaii; she arrived at Pearl Harboron 27 May, entering dry dock the following day. The damage the ship hadsustained after Coral Sea was considerable, and led to the Navy Yard inspectorsestimating that she would need at least two weeks of repairs. However, AdmiralNimitz ordered that she be made ready to sail alongside TF 16. Furtherinspections showed that Yorktown's flight elevators had not been damaged, andthe damage to her flight deck and hull could be patched easily. Yard workers atPearl Harbor, laboring around the clock, made enough repairs to enable the shipto put to sea again in 48 hours. The repairs were made in such a short timethat the Japanese Naval Air Commanders would mistake Yorktown for anothercarrier as they thought she had been sunk during the previous battle. However,one critical repair to her power plant was not made: her damaged superheaterboilers were not touched, limiting her top speed. Her air group was augmentedby planes and crews from Saratoga which was then headed for Pearl Harbor afterher refit on the West Coast. Yorktown sailed as the core of TF 17 on 30 May.

Northeast of Midway, Yorktown, flying Vice Admiral Fletcher's flag,rendezvoused with TF 16 under Rear Admiral Raymond A. Spruance and maintained aposition 10 miles (16 km) to the northward of him.

Patrols, both from Midway and the carriers, were flown during early June. Atdawn on 4 June Yorktown launched a 10-plane group of Dauntlesses from VB-5which searched a northern semicircle for a distance of 100 miles (160 km) outbut found nothing.

Meanwhile, PBYs flying from Midway had sighted the approaching Japanese andbroadcast the alarm for the American forces defending the key atoll. AdmiralFletcher, in tactical command, ordered Admiral Spruance's TF 16 to locate andstrike the enemy carrier force.

Yorktown's search group returned at 08:30, landing soon after the last of thesix-plane CAP had left the deck. When the last of the Dauntlesses wererecovered, the deck was hastily respotted for the launch of the ship's attackgroup: 17 Dauntlesses from VB-3, 12 Devastators from VT-3, and six Wildcatsfrom "Fighting Three". Enterprise and Hornet, meanwhile, launchedtheir attack groups.

The torpedo planes from the three American carriers located the Japanesestriking force, but met disaster. Of the 41 planes from VT-8, VT-6, and VT-3,only six returned to Enterprise and Yorktown; none made it back to Hornet.

As a reaction to the torpedo attack the Japanese CAP had broken off theirhigh-altitude cover for their carriers and had concentrated on the Devastators,flying "on the deck", allowing Dauntlesses from Yorktown andEnterprise to arrive unopposed.

Virtually unopposed, Yorktown's dive-bombers attacked Sōryū, making threelethal hits with 1,000 pounds (450 kg) bombs and setting her on fire.[8]Enterprise's planes, meanwhile, hit Akagi and Kaga, effectively destroyingthem. The bombs from the Dauntlesses caught all of the Japanese carriers in themidst of refueling and rearming operations, causing devastating fires andexplosions.

Three of the four Japanese carriers had been left burning wrecks. The fourth,Hiryū, separated from her sisters, launched a striking force of 18"Vals" and soon located Yorktown.

As soon as the attackers had been picked up on Yorktown's radar at about 13:29,she discontinued fueling her CAP fighters on deck and swiftly cleared foraction. Her returning dive bombers were moved from the landing circle to openthe area for antiaircraft fire. The Dauntlesses were ordered aloft to form aCAP. An auxiliary 800-US-gallon (3,000 L) gasoline tank was pushed over thecarrier's fantail, eliminating one fire hazard. The crew drained fuel lines andclosed and secured all compartments.[5]

All of Yorktown's fighters were vectored out to intercept the oncoming Japaneseaircraft at a distance of 15 to 20 miles (24 to 32 km) out. The Wildcatsattacked vigorously, breaking up what appeared to be an organized attack bysome 18 "Vals" and 6 "Zeroes".[9] "Planes were flyingin every direction", wrote Captain Buckmaster after the action, "andmany were falling in flames."[5] The leader of the "Vals",Lieutenant Michio Kobayashi, was probably shot down by the VF-3's commandingofficer, Lieutenant Commander John S. Thach. Lieutenant William W. Barnes alsopressed home the first attack, possibly taking out the lead bomber and damagingat least two others.

Despite an intensive barrage and evasive maneuvering, three "Vals"scored hits. Two of them were shot down soon after releasing their bomb loads;the third went out of control just as his bomb left the rack. It tumbled inflight and hit just abaft the number two elevator on the starboard side,exploding on contact and blasting a hole about 10 feet (3 m) square in theflight deck. Splinters from the exploding bomb killed most of the crews of thetwo 1.1-inch (28 mm) gun mounts aft of the island and on the flight deck below.Fragments piercing the flight deck hit three planes on the hangar deck,starting fires. One of the aircraft, a Yorktown Dauntless, was fully fueled andcarrying a 1,000 pounds (450 kg) bomb. Prompt action by LT A. C. Emerson, thehangar deck officer, prevented a serious fire by activating the sprinklersystem and quickly extinguishing the fire.

The second bomb to hit the ship came from the port side, pierced the flightdeck, and exploded in the lower part of the funnel, in effect a classic"down the stack shot." It ruptured the uptakes for three boilers,disabled two boilers, and extinguished the fires in five boilers. Smoke andgases began filling the firerooms of six boilers. The men at Number One boilerremained at their post and kept it alight, maintaining enough steam pressure toallow the auxiliary steam systems to function.

A third bomb hit the carrier from the starboard side, pierced the side ofnumber one elevator and exploded on the fourth deck, starting a persistent firein the rag storage space, adjacent to the forward gasoline stowage and themagazines. The prior precaution of smothering the gasoline system with carbondioxide undoubtedly prevented the gasoline from igniting.

While the ship recovered from the damage inflicted by the dive-bombing attack,her speed dropped to 6 knots (11 km/h; 6.9 mph); and then at 14:40, about 20minutes after the bomb hit that had shut down most of the boilers, Yorktownslowed to a stop, dead in the water.

At about 15:40, Yorktown prepared to get underway; and, at 15:50, thanks to theblack gang in No. 1 Fireroom having kept the auxiliaries operating to clear thestack gas from the other firerooms and bleeding steam from No. 1 to the otherboilers to jump-start them, Chief Engineer Delaney reported to CaptainBuckmaster that the ship's engineers were ready to make 20 knots (37 km/h; 23mph) or better. Yorktown yanked down her yellow breakdown flag and up went anew hoist-"My speed 5." Captain Buckmaster had his signalmen hoist ahuge new (10 feet wide and 15 feet long) American flag from the foremast.Sailors, including Ensign John d'Arc Lorenz called it an incalculableinspiration: "For the first time I realized what the flag meant: all of us— a million faces — all our effort — a whisper of encouragement." Damagecontrol parties were able to temporarily patch the flight deck and restorepower to several boilers within an hour, giving her a speed of 19 knots (35km/h; 22 mph) and enabling her to resume air operations.

Simultaneously, with the fires controlled sufficiently to warrant theresumption of fueling, Yorktown began refueling the fighters then on deck; justthen the ship's radar picked up an incoming air group at a distance of 33 miles(53 km). While the ship prepared for battle, again smothering gasoline systemsand stopping the fueling of the planes on her flight deck, she vectored four ofthe six fighters of the CAP in the air to intercept the raiders. Of the 10fighters on board, eight had as little as 23 US gallons (87 L) of fuel in theirtanks. They were launched as the remaining pair of fighters of the CAP headedout to intercept the Japanese planes.

At 16:00, maneuvering Yorktown churned forward, making 20 knots. The fightersshe had launched and vectored out to intercept had meanwhile made contact withthe enemy. Yorktown received reports that the planes were "Kates".The Wildcats shot down at least three, but the rest began their approach whilethe carrier and her escorts mounted a heavy antiaircraft barrage.

Yorktown maneuvered radically, avoiding at least two torpedoes before anothertwo struck the port side within minutes of each other, the first at 16:20. Thecarrier had been mortally wounded; she lost power and went dead in the waterwith a jammed rudder and an increasing list to port.

As the ship's list progressed, Commander Clarence E. Aldrich, the damagecontrol officer, reported from central station that, without power, controllingthe flooding looked impossible. The Chief Engineer, Lieutenant Commander JohnF. Delaney, soon reported that all boiler fires were out, all power was lost,and that it was impossible to correct the list. Buckmaster ordered Aldrich,Delaney, and their men to secure the fire and engine rooms and lay up to theweather decks to put on life jackets.

The list, meanwhile, continued to increase. When it reached 26 degrees,Buckmaster and Aldrich agreed that capsizing was imminent. "In order tosave as many of the ship's company as possible", the captain wrote later,he "ordered the ship to be abandoned".

Over the next few minutes the crew lowered the wounded into life rafts andstruck out for the nearby destroyers and cruisers to be picked up by theirboats, abandoning ship in good order. After the evacuation of all wounded, theexecutive officer, Commander Dixie Kiefer left the ship down a line on thestarboard side. Buckmaster, meanwhile, toured the ship one last time, to see ifany men remained. After finding no "live personnel", Buckmasterlowered himself into the water by means of a line over the stern, by which timewater was lapping the port side of the hangar deck.[5]

After being picked up by the destroyer USS Hammann, Buckmaster transferred tothe cruiser Astoria and reported to Vice Admiral Fletcher, who had shifted hisflag to the heavy cruiser after the first dive-bombing attack. The two menagreed that a salvage party should attempt to save the ship since she hadstubbornly remained afloat despite the heavy list and imminent danger ofcapsizing.

While efforts to save Yorktown had been proceeding apace, her planes were stillin action, joining those from Enterprise in striking the last Japanesecarrier—Hiryū—late that afternoon. Taking four direct hits, the Japanesecarrier was soon helpless. She was abandoned by her crew and left to drift outof control.

Yorktown, as it turned out, floated throughout the night. Two men were stillalive on board her; one attracted attention by firing a machine gun, heard bythe sole attending destroyer, Hughes. The escort picked up the men, one of whomlater died. Buckmaster selected Executive Officer Dixie Kiefer commander of thesalvage crew which also included 29 officers and 141 men to return to the shipin an attempt to save her. Five destroyers formed an antisubmarine screen whilethe salvage party boarded the listing carrier on the morning of 6 June. Thefleet tug USS Vireo, summoned from Pearl and Hermes Reef, commenced towing theship, although progress was painfully slow.

Yorktown's repair party went on board with a carefully predetermined plan ofaction to be carried out by men from each department—damage control, gunneryair engineering, navigation, communication, supply and medical. To assist inthe work, Lieutenant Commander Arnold E. True brought Hammann alongside tostarboard, aft, furnishing pumps and electric power.

By mid-afternoon, the process of reducing topside weight was proceeding well;one 5-inch (127 mm) gun had been dropped over the side and a second was readyto be cast loose, planes had been pushed over the side, and a large quantity ofwater had been pumped out of engineering spaces. These efforts reduced the listby about two degrees.

Unknown to Yorktown and the six nearby destroyers, however, Japanese submarineI-168 had discovered the disabled carrier and achieved a favorable firingposition. The I-boat eluded detection—possibly due to the large amount ofdebris and wreckage in the water—until 15:36, when lookouts spotted a salvo offour torpedoes approaching the ship from the starboard beam.

Hammann went to general quarters, with a 20-millimeter gun going into action inan attempt to explode the torpedoes in the water as she tried to get underway.One torpedo hit Hammann directly amidships and broke her back. The destroyerjackknifed and went down rapidly. Two torpedoes struck Yorktown at the turn ofthe bilge at the after end of the island structure. The fourth torpedo passedastern of the carrier.

About a minute after Hammann sank there was an underwater explosion, possiblycaused by the destroyer's depth charges going off. The concussion killed manyof Hammann's and a few of Yorktown's men who had been thrown into the water,battered the damaged carrier's hull, dislodged Yorktown's auxiliary generatorand numerous fixtures from the hangar deck, sheared rivets in the starboard legof the foremast, and injured several onboard crew members. The remainingdestroyers initiated a search for the enemy submarine (which escaped), andcommenced rescue operations for Hammann survivors and the Yorktown salvagecrew. Vireo cut the tow and doubled back to assist in rescue efforts.

Throughout the night of 6 June and into the morning of 7 June, Yorktown remained afloat; but by 05:30 on 7 June, observers noted that her list wasrapidly increasing to port. Shortly afterwards, the ship turned over onto herport side, and lay afloat for several minutes, revealing the torpedo hole inher starboard bilge- the result of the submarine attack. Captain Buckmaster'sAmerican flag was still flying. All ships half-masted their colors in salute;all hands who were topside with heads uncovered came to attention, with tearsin their eyes. Two patrolling PBYs appeared overhead and dipped their wings ina final salute. At 07:01, the ship rolled upside-down, and slowly sank, sternfirst, in 3,000 fathoms (5,500 m) of water with her battle flags flying. Tomost who witnessed the sinking, the Yorktown went quietly and with enormousdignity- "like the great lady she was," as one of them put it. Inall, Yorktown's sinking on 7 June 1942 claimed the lives of 141 of her officersand crewmen. (Wikipedia)

_is_hit_by_a_torpedo_on_4_June_1942.webp)

(USN Photo)

USS Yorktown (CV-5) is hit on the port side, amidships, by a Japanese Type 91 aerial torpedo during the mid-afternoon attack by planes from the carrier Hiryu, in the Battle of Midway, on 4 June, 1942. Yorktown is heeling to port and is seen at a different aspect than in other views taken by USS Pensacola (CA-24), indicating that this is the second of the two torpedo hits she received. Note very heavy anti-aircraft fire.

USS Enterprise (CV-6)

USS Enterprise (CV-6). Commissioned 12 May 1938. She was the most decorated naval vessel in the Second World War, and played a vital role in the Pacific. At the decisive Battle of Midway, she sank enemy warships, including three carriers. The ship supported the Guadalcanal Campaign and engaged in battles at Eastern Solomons and Santa Cruz Islands. Enterprise participated in major operations, including the Marianas and Philippine Sea, and the Battle of Leyte Gulf. Despite kamikaze damage, it stayed active, transporting U.S. servicemen before being decommissioned and sold for scrapping.

_and_USS_Lexington_(CV-16)_at_sea_in_June_1944.webp)

(USN Photo)

USS Enterprise (CV-6) (foreground) steaming with USS Lexington (CV-16) in the Central Pacific in June 1944.

(USN Photo)

U.S. Navy destroyer USS Fanning (DD-385) maneuvers near the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6) on the day the "Doolittle Raid" aircraft were launched from the USS Hornet (CV-8), on 18 April 1942. The photo was taken from the heavy cruiser USS Salt Lake City (CA-25).

_docked_at_Ford_Island%2C_in_May_1942.jpg)

(USN Photo)

U.S. Navy aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6) at Ford Island, Pearl Harbor, in May 1942, shortly before the Battle of Midway. Note the "nest" with 2x20mm Oerlikon guns on her bow under the flying deck which were installed at the end of March before the Doolittle Raid. The sunken battleship USS West Virginia (BB-48) is visible on the left.

(USN Photo)

U.S. Navy Torpedo Squadron 6 (VT-6) Douglas TBD-1 Devastator aircraft are prepared for launching aboard the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6) at about 0730-0740 hrs, 4 June 1942. Eleven of the fourteen TBDs launched from Enterprise are visible. Three more TBDs and ten Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat fighters must still be pushed into position before launching can begin. The TBD in the left front is Number Two (BuNo 1512), flown by Ensign Severin L. Rombach and Aviation Radioman 2nd Class W.F. Glenn. Along with eight other VT-6 aircraft, this plane and its crew were lost attacking Japanese aircraft carriers somewhat more than two hours later. The heavy cruiser USS Pensacola (CA-24) is in the right distance and a destroyer is in plane guard position at left.

(USN Photo)

U.S. Navy Douglas SBD-2 Dauntless dive bomber of either Bombing Squadron 6 (VB-6) or Scouting Squadron 6 (VS-6) aboard the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6) prepares for takeoff during the 1 February 1942 Marshall Islands Raid.

(USN Photo)

A Japanese bomb explodes off the port side of the U.S. Navy aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6) during the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, 26 October 1942.

(USN Photo)

Crash landing of a U.S. Navy Grumman F6F-3 Hellcat (Number 30) of Fighting Squadron 2 (VF-2) aboard the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6), into the carrier's port side 20mm gun gallery, 10 November 1943. Lieutenant Walter L. Chewning, Jr., USNR, the Catapult Officer, is seen climbing up the plane's side to assist the pilot from the burning aircraft. The pilot, Ensign Byron M. Johnson, escaped without significant injury. Enterprise was then en route to support the Gilberts Operation. Note the plane's ruptured belly fuel tank.

(USN Photo)

A U.S. Navy Grumman TBF-1 Avenger of Torpedo Squadron 6 (VT-6) flies over the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6) as she conducts flight operations in the Central Pacific while supporting the Gilberts Operation, 22 November 1943.

_in_Puget_Sound%2C_September_1945.jpg)

(USN Photo)

U.S. Navy aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6) making 20 knots during post-overhaul trials in Puget Sound, Washington (USA), on 13 September 1945

(USN Photo)

In mid-1944, the USS Enterprise (CV-6), was anchored off Saipan, a key island in the Marianas.At this time, the ship was painted in camouflage Measure 33, Design 4Ab, a pattern designed to confuse enemy radar and visual targeting systems, blending the ship into the surrounding sea and sky.The Measure 33, Design 4Ab camouflage was a complex pattern of light and dark colours, using shades of gray and blue, designed to reduce the visibility of the ship from various angles.This camouflage was particularly useful in the Pacific theater, where the intense sunlight and vast distances between islands made it difficult to hide massive ships like the Enterprise.The pattern helped break up the ship's outline, making it harder for enemy aircraft or surface ships to target accurately.

(USN Photo)

U.S. Navy aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6) steams toward the Panama Canal on 10 October 1945, while en route to New York (USA) to participate in Navy Day celebrations

USS Hornet (CV-8)

USS Hornet (CV-8). Commissioned 20 Oct 1941. She was the first of two carriers to be named Hornet and fight in the Second World War. She participated in pivotal moments of the war, including the Doolittle Raids, Battle of the Coral Sea, and the Battle of Midway. The Hornet’s planes contributed to the sinking of the Japanese cruiser Mikuma. Severely damaged during the Battle of Santa Cruz, the carrier remained afloat until eventually sunk by Japanese submarines. In 2019, the wreckage of the Hornet was discovered near the Solomon Islands.

_underway_in_Hampton_Roads_on_27_October_1941.webp)

(USN Photo)

USS Hornet (CV-8) underway in Hampton Roads, Virginia, on 27 October 1941.

(USN Photo)

A Japanese Type 99 Aichi D3A1 dive bomber (Allied codename "Val") trails smoke as it dives toward the U.S. Navy aircraft carrier USS Hornet (CV-8), during the morning of 26 October 1942. This plane struck the ship's stack and then her flight deck. A Type 97 Nakajima B5N2 torpedo plane ("Kate") is flying over Hornet after dropping its torpedo, and another "Val" is off her bow. Note anti-aircraft shell burst between Hornet and the camera, with its fragments striking the water nearby.

Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands

The Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands took place on 26 October 1942 withoutcontact between surface ships of the opposing forces. That morning,Enterprise's planes bombed the carrier Zuihō, while planes from Hornet severelydamaged the carrier Shōkaku and the heavy cruiser Chikuma. Two other cruiserswere also attacked by Hornet's aircraft. Meanwhile, Hornet was attacked by acoordinated dive bomber and torpedo plane attack.[12] In a 15-minute period,Hornet was hit by three bombs from Aichi D3A "Val" dive bombers. One"Val", after being heavily damaged by antiaircraft fire whileapproaching Hornet, crashed into the carrier's island, killing seven men andspreading burning aviation gas over the deck. A flight of Nakajima B5N"Kate" torpedo bombers attacked Hornet and scored two hits, whichseriously damaged the electrical systems and engines. As the carrier came to ahalt, another damaged "Val" deliberately crashed into Hornet's portside near the bow.

With power knocked out to her engines, Hornet was unable to launch or landaircraft, forcing her aviators to either land on Enterprise or ditch in theocean. Rear Admiral George D. Murray ordered the heavy cruiser Northampton totow Hornet clear of the action. Japanese aircraft were attacking Enterprise,allowing Northampton to tow Hornet at a speed of about five knots (9 km/h; 6mph). Repair crews were on the verge of restoring power when another flight ofnine "Kate" torpedo planes attacked. Eight of these aircraft wereeither shot down or failed to score hits, but the ninth scored a fatal hit onthe starboard side. The torpedo hit destroyed the repairs to the electricalsystem and caused a 14° list. After being informed that Japanese surface forceswere approaching and that further towing efforts were futile, Vice AdmiralWilliam Halsey ordered Hornet sunk, and an order of "abandon ship" was issued. Captain Mason, the last man on board, climbed over the side, and the survivors were soon picked up by the escorting destroyers.

American warships attempted to scuttle the stricken carrier, which absorbednine torpedoes, many of which failed to explode, and more than 400 5-inch (127mm) rounds from the destroyers Mustin and Anderson. The destroyers steamed awaywhen a Japanese surface force entered the area. The Japanese destroyers Makigumo and Akigumo finally finished off Hornet with 4 24-inch (610 mm) LongLance torpedoes. At 01:35 on 27 October, Hornet finally capsized to starboardand sank, stern first, with the loss of 140 of her 2,200 sailors. 21 aircraftwent down with the ship. (Wikipedia)

Wasp-class

USS Wasp (CV-7) was a United States Navy aircraft carrier commissioned in 1940 and lost in action in 1942. She was the eighth ship named USS Wasp, and the sole ship of a class built to use up the remaining tonnage allowed to the U.S. for aircraft carriers under the treaties of the time. As a reduced-size version of the Yorktown-class aircraft carrierhull, Wasp was more vulnerable than other United States aircraft carriers available at the opening of hostilities.

USS Wasp (CV-7)

Wasp was initially employed in the Atlantic campaign, where Axis naval forces were perceived as less capable of inflicting decisive damage. After supporting the occupation of Iceland in 1941, Wasp joined the British Home Fleet in April 1942 and twice ferried British fighter aircraft to Malta. Wasp was then transferred to the Pacific in June 1942 to replace losses at the battles of Coral Sea and Midway. After supporting the invasion of Guadalcanal, Wasp was hit by three torpedoes from Japanese submarine I-19 on 15 September 1942. The resulting damage set off several explosions, destroyed her water-mains and knocked out the ship's power. As a result, her damage-control teams were unable to contain the ensuing fires that blazed out of control. She was abandoned and scuttled by torpedoes fired from USS Lansdowne later that evening. Her wreck was found in early 2019. (Wikipedia)

_on_27_December_1940_(520814).webp)

(USN Photo)

USS Wasp (CV-7) on 27 December 1940.

_entering_Hampton_Roads_on_26_May_1942.webp)

(USN Photo)

USS Wasp (CV-7) entering Hampton Roads, Virginia, on 26 May 1942. The escorting destroyer USS Edison (DD-439) is visible in the background.

(USN Photo)

USS Wasp (CV-7) burning after receiving three torpedo hits from the Japanese submarine I-19 east of the Solomons, 15 September 1942.

USS Wasp (CV-7). Commissioned 25 Apr 1940. The first of two aircraft carriers in the Second World War to be named Wasp, she was commissioned in 1940 and lost in action in 1942. A smaller version of the Yorktown-class carriers, the Wasp began in the Atlantic campaign and later was transferred to the Pacific. She participated in the invasion of Guadalcanal but was hit by three torpedoes in September 1942, leading to its abandonment and scuttling.