Castles in Germany: Medieval Fortresses, Burgen, Festung, and Schlosser, Part 2

German Medieval Castles and Fortresses

(Burgen, Festung und Schlosser)

(Author's artwork)

Burg Gutenfels overlooking Pfalzgrafenstein, on the Rhine River, Germany, Oil on canvas, 18 X 24.

(Author Photo)

Kaub: Burg Gutenfels and Pfalzgrafenstein on the Rhine River.

(Author Photos)

Burg Gutenfels on the Rhine River, Germany.

(Author Photo)

Kaub: Burg Pfalzgrafenstein is a toll castle on Falkenau island, otherwise known as Pfalz Island in the Rhine River

near Kaub, Germany. Known as "the Pfalz," this former stronghold is famous for its picturesque and unique setting.

The keep of this island castle, a pentagonal tower with its point upstream, was erected 1326 to 1327 by King Ludwig

the Bavarian. Around the tower, a defensive hexagonal wall was built between 1338 to 1340. In 1477

Pfalzgrafenstein was passed as deposit to the Count of Katzenelnbogen. Later additions were made in 1607 and

1755, consisting of corner turrets, the gun bastion pointing upstream, and the characteristic baroque tower cap.

The castle functioned as a toll-collecting station that was not to be ignored. It worked in concert with Gutenfels

Castle and the fortified town of Kaub on the right side of the river. Due to a dangerous cataract on the river's left,

about a kilometer upstream, every vessel would have to use the fairway nearer to the right bank, thus floating

downstream between the mighty fortress on the vessel's left and the town and castle on its right. A chain across

the river drawn between those two fortifications forced ships to submit, and uncooperative traders could be kept

in the dungeon until a ransom was delivered. The dungeon was a wooden float in the well.

Unlike the vast majority of Rhine castles, "the Pfalz" was never conquered or destroyed, withstanding not only

wars, but also the natural onslaughts of ice and floods by the river. Its Spartan quarters held about twenty men.

(Author Photo)

Burg Pfalzgrafenstein on the Rhine River. There is a plaque marking this as site where General Blucher crossed the

ice-covered river with his army during the Napoleonic Wars before 1815.

(Ulli1105 Photo, 19 June 2005)

Burg Berwartstein was one of the most interesting castles that I have a clear memory of, with my parents taking us to visit it

on 27 March 1960. It stands on a rocky mount in southwestern Germany, and was one of the rcok castles that were

part of defences of the Palatinate during the Middle Ages. First documented in 1152, Berwarstein is one of three

significant examples of rock castles in the region with the other two being Drachenfels and Altdahn. They are most

notable because their stairs, passages and rooms are carved out of the living rock to form part of the accommodation

essential to the defence of the castle. Although Berwartstein Castle appears more complete when compared to the ruins

of neighboring castles, it is only a restoration of the original rock castle. It is the only castle in the Palatinate that was

rebuilt and re-inhabited after its demolition. (Visited 27 Mar 1982, 28 Nov 1982, 5 March 1990, 16 May 1990, May 2008, fall 1997)

(Claus Ableiter Photo)

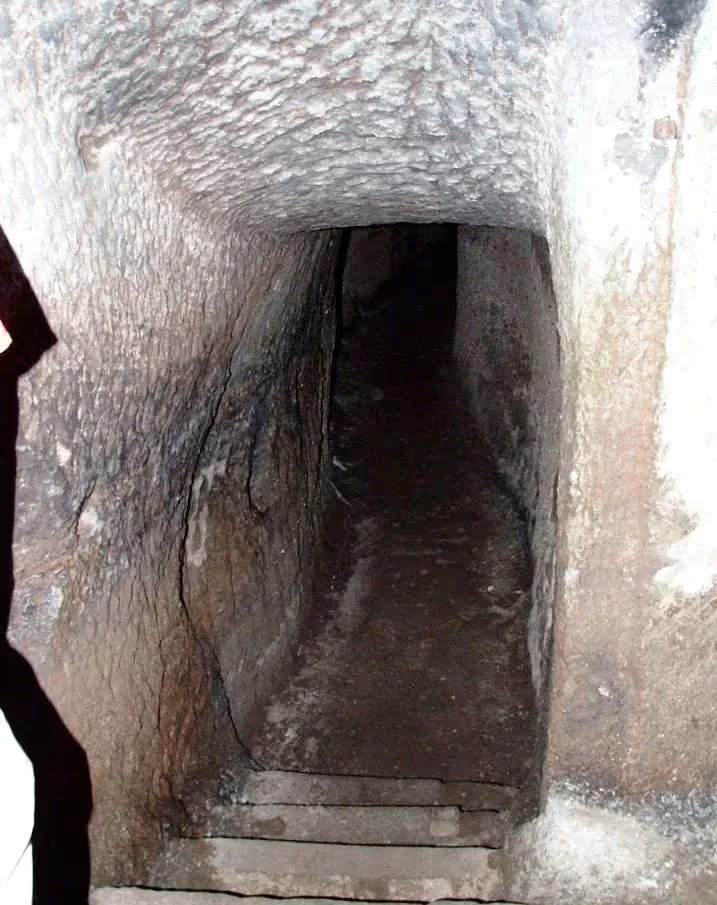

Rock cut passageways leading under Berwartstein. Carved out of the cliff and accessible even today are corridors

and passageways which used to be part of the large underground defence network. Although not accessible today,

there was once a tunnel from the castle to the village below. These tunnels were hewn out with hammer and chisel

and partly dug through the soil.

One memory I have from those days, is that the guide took a group of us through an underground tunnel that wound

some distance from the entrance to the interior storage chamber. The guide was the only one with a flashlight, so

we all joined hands in a chain link to go through the dark path (cobwebs and all). On reaching the other end we

came into a room dubbed "casemate II", with a central pillar holding up the ceiling - it had been carved out of the

living rock!

(CB Photo)

Casemate II, as it appeared when we came out of the tunnel - quite the introduction to castle tunnel spelunking!

I remember my father explaining that the robber knights operating from this castle created a problem for the rulers

in the area, so they commissioned one of their best knights to go and sort them out. He managed to get the best of

them, but on reflection decided they had a pretty good scheme going, and so he joined them, taking over the business,

so to speak. Even more remarkable, the fortress was so well defended, the Robber Knight died of old age, quite

rare for the profession. I am going to include some details of this castle, much of which is typical of the many I

have explored during our time in Germany.

(Franz Photo, 1 Oct 2011)

Armour and stone catapult/cannon balls. At the age of eight, these were the first I had seen.

During the 13th century, feudal tenants, who carried the name "von Berwartstein" inhabited the castle, which they

used as a base for raids in the manner of robber barons. The imperial cities of Strasbourg and Hagenau joined

forces against the von Berwartsteins. Following several weeks of futile attacks against the castle, they succeeded

in taking it in 1314, with the help of a traitor. A large amount of booty and about 30 prisoners were taken to

Strasbourg. The knights of Berwartstein were permitted to buy the prisoners back for a large ransom. The

knights of Berwartstein were forced to sell their castle to the brothers Ort and Ulrich von Weingarten. Four

years later the castle became the property of Weissenburg Abbey.

The monastery at Weissenburg placed the castle in stewardship and established a feudal system. This allowed

for the dismissal of vassals who became too presumptuous. Thus the monastery held possession of the castle

for some time. This could have continued indefinitely had the last steward of the castle (Erhard Wyler) not gone

too far. When he began feuding with the knights of Drachenfels, the Elector of the Palatinate took the opportunity

to bring the Berwartstein Castle under his control.

Because of his dynastic ambitions, the Elector of the Palatinate wanted to bring all of the Weissenburg estate under

his control. To accomplish this, in 1480 he ordered the knight, Hans von Trotha, who was Marshal and Commander

in Chief of the Palatinate forces, to acquire to Berwartstein. In this way he could enlarge the property at a cost to

the Monastery of Weissenburg. For the quarrelsome knight this was a pleasure to fulfil, since this gave him a chance

to take personal revenge on the Abbot of Weissenburg. Years before, Abbot Heinrich von Homburg had imposed a

church fine on his brother, Bishop Thilo. As a starting point for this conquering expedition, this experienced warrior

first renovated the castle to improve its appearance. He built strong ramparts and bastions as well as the outwork

and tower called Little France castle.

After von Trotha's death, Berwartstein Castle was inherited by his son Christoph and, when he died, it went to his

son-in-law, Friedrich von Fleckenstein and remained in the hands of this family for three generations. During this

time, the castle was destroyed by fire in 1591, and, since there is no mention of any attacks, it is presumed that the

castle was hit by lightning. Even though the main sections of the castle were not destroyed by the fire, it stood

empty and unused for many years. In the Peace of Westphalia (1648), Berwartstein received special mention,

when it was granted to Baron Gerhard von Waldenburg, known as Schenkern, a favorite of Emperor Ferdinand III.

Since he did not restore the castle, it fell into ruins.

A certain Captain Bagienski purchased the castle in 1893. In 1922, it was sold to Aksel Faber of Copenhagen,

and thus went into foreign ownership. Since he was seldom in Germany, he asked Alfons Wadlé to be his steward.

Later Wadlé he was able to purchase the castle.

The village of Erlenbach below the castle was completely destroyed during the Second World War, and its

inhabitants sought shelter in the castle. After the war, the roof had gone as well as the woodwork around windows,

doors, staircases and other furnishings. Since the castle was not financially supported, Alfons Wadlé went about

the renovation himself. At first he was only able to do what was essential to protect the castle from the elements.

Berwartstein has an opening on the southeast side of the cliff, commonly referred to as Aufstiegskamin (entrance

chimney). During the early years of the castle only the rooms and casemates in the upper cliff were complete and

the shaft was the only entrance to the castle. To make it easier to ascend the shaft, a portable wooden staircase or

rope ladder was placed into the castle. In the event of attack, the staircase or ladder was hoisted up into the castle.

This enabled the entrance to be defended by just one man who was supplied with boiling sap, oil or liquid to pour

on any intruder attempting to ascend the shaft. This limited access to the castles inner rooms was probably the

main reason it was never conquered during the Middle Ages. The narrow, almost vertical cliff on which the castle

stands, rises to a height of approximately 45 metres.

(H. Zell Photo)

The extremely deep well is one of the castle builders' greatest accomplishments. The well has a diameter of 2 metres

(6 ft) and was hacked out of the rock to the bottom of the valley some 104 metres (341 feet) below. This was

essential to the castle's survival when under siege.

The historic Great Hall or Rittersaal has a cross-vaulted ceiling. An engraving on the supporting central pillar

shows that it dates to the 13th century. The south wall of the hall is made from rock and includes a hewn-out lift

shaft used by the knights of Berwartstein to deliver supplies to the table and deliver food and drink from the kitchen

above.

(Ulli1105 Photo)

To the south on the opposite side of the valley from the castle on a spur of the Nestelberg can still be seen the tower

of Little France. This tower was part of an outwork or small subsidiary castle built by the well known knight and

castellan of the Berwartstein, Hans von Trotha. The tower was an important observation post and defensive position,

and meant that any attackers would have found themselves caught in a crossfire between the tower and the castle.

The open ground in the valley below between the tower and castle still bears the name Leichenfeld (Corpse Field),

a reference to the battles fought here. There is also evidence of an underground passage between the tower and

castle which is no longer accessible today since it has largely collapsed.

(ArtMechanic Photo)

Nürnberger Burg with a view of the Palas, Imperial Chapel, Heathens' Tower on the left, Sinwell Tower in the

middle left, the Pentagonal Tower, the Imperial Stables and Luginsland Tower on the right. In the Middle Ages,

German Kings, (respectively Holy Roman Emperors after their coronation by the Pope) did not have a capital,

but travelled from one of their castles (Kaiserpfalz or Imperial castle) to the next. For this reason, the castle at

Nürnberg became an important imperial castle, and in the following centuries, all German kings and emperors

stayed at the castle, most of whom did so on several occasions. Nuremberg Castle is comprised of three sections:

the Imperial castle (Kaiserburg), the former Burgraves' castle (Burggrafenburg), and the buildings erected by the

Imperial City at the eastern site (Reichsstädtische Bauten).

The first fortified buildings appear to have been erected around 1000. Thereafter, three major construction periods

may be distinguished: The castle was built under the Salian kings respectively Holy Roman Emperors (1027–1125).

A new castle was built under the Hohenstaufen emperors (1138–1254). Reconstruction of the Palas as well as various

modifications and additions in the late medieval centuries took place.

The castle lost its importance after the Thirty Year's War (1618 to 1648). In the 19th century with its general

interest in the medieval period, some modifications were added. During the Nazi period, in preparation of the

Nuremberg party rally in 1936, it was "returned to its original state." A few years later, during the Second World

War and its air raids in 1944/1945, a large part of the castle was laid in ruins. It took some thirty years to complete

the rebuilding and restoration to its present state.

(Kolossos Photo)

Nürnberger Burg, Tiefer Brunnen (deep well, small building with gable roof in the middle) and Sinwellturm

(Sinwell Tower). The complex consists of a group of medieval fortified buildings on a sandstone ridge ridge

dominating the historical center of Nuremberg in Bavaria, Germany. The castle, together with its city walls, was

considered to be one of Europe's most formidable medieval fortifications. It represented the power and importance

of the Holy Roman Empire and the outstanding role of the Imperial City of Nuremberg.

(Author Photo)

Eisenach: Wartburg Castle, overlooking the town of Eisenach in the state of Thuringia, Germany, 27 May 2016. Originally

built in Middle Ages, The Wartburg stands on a cliff rising 410 meters (1,350 ft) to the southwest of and overlooking

the town of Eisenach, in the state of Thuringia, Germany. It was the home of St. Elisabeth of Hungary, the place

where Martin Luther translated the New Testament of the Bible into German, the site of the Wartburg festival of

1817 and the supposed setting for the possibly legendary Sängerkrieg. It was an important inspiration for Ludwig II

when he decided to build Neuschwanstein Castle. The Wartburg castle contains substantial original structures from

the 12th through 15th centuries, but much of the interior dates back only to the 19th century.

The castle's foundation was laid about 1067 by the Thuringian count of Schauenburg, Ludwig der Springer, a

relative of the Counts of Rieneck in Franconia. Together with its larger sister castle Neuenburg in the present-day

town of Freyburg, the Wartburg secured the extreme borders of his traditional territories. Ludwig der Spring is

said to have had clay from his lands transported to the top of the hill, which was not quite within his lands, so he

might swear that the castle was built on his soil.

The castle was first mentioned in a written document in 1080 by Bruno, Bishop of Merseburg, in his De Bello

Saxonico ("The Saxon War") as Wartberg. During the Investiture Controversy, Ludwig's henchmen attacked a

military contingent of King Henry IV of Germany. The count remained a fierce opponent of the Salian rulers, and

upon the extinction of the line, his son Louis I was elevated to the rank of a Landgrave in Thuringia by the new

German king Lothair of Supplinburg in 1131.

From 1172 to 1211, the Wartburg was one of the most important princes' courts in the German Reich. Hermann I

supported poets like Walther von der Vogelweide and Wolfram von Eschenbach who wrote part of his Parzival

here in 1203.

The castle thus became the setting for the legendary Sängerkrieg, or Minstrels' Contest in which such Minnesänger

as Walther von der Vogelweide, Wolfram von Eschenbach, Albrecht von Halberstadt (the translator of Ovid) and

many others supposedly took part in 1206/1207. The legend of this event was later used by Richard Wagner in

his opera Tannhäuser.

At the age of four, St. Elisabeth of Hungary was sent by her mother to the Wartburg to be raised to become consort

of Landgrave Ludwig IV of Thuringia. From 1211 to 1228, she lived in the castle and was renowned for her charitable

work. In 1221, Elisabeth married Ludwig. In 1227, Ludwig died on the Crusade and she followed her confessor

Father Konrad to Marburg. Elisabeth died there in 1231 at the age of 24 and was canonized as a saint of the Roman

Catholic Church, just five years after her death.

In 1247, Heinrich Raspe, the last landgrave of Thuringia of his line and an anti-king of Germany, died at the Wartburg.

He was succeeded by Henry III, Margrave of Meissen.

In 1320, substantial reconstruction work was done after the castle had been damaged in a fire caused by lightning in

1317 or 1318. A chapel was added to the Palas. The Wartburg remained the seat of the Thuringian landgraves until

1440. From May 1521 to March 1522, Martin Luther stayed at the castle under the name of Junker Jörg (the Knight

George), after he had been taken there for his safety at the request of Frederick the Wise following his

excommunication by Pope Leo X and his refusal to recant at the Diet of Worms. It was during this period that Luther

translated the New Testament from ancient Greek into German in just ten weeks. Luther's work was not the first

German translation of the Bible but it quickly became the most well known and most widely circulated.

From 1540 until his death in 1548, Fritz Erbe, an Anabaptist farmer from Herda, was held captive in the dungeon

of the south tower, because he refused to abjure anabaptism. After his death, he was buried in the Wartburg near

the chapel of St. Elisabeth. In 1925, a handwritten signature of Fritz Erbe was found on the prison wall. Over the

next few centuries, the castle fell increasingly into disuse and disrepair, especially after the end of the Thirty Years'

War when it had served as a refuge for the ruling family. In 1777, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe stayed at the

Wartburg for five weeks, making various drawings of the buildings.

On 18 October 1817, the first Wartburg festival took place. About 500 students, members of the newly founded

German Burschenschaften (fraternities), came together at the castle to celebrate the German victory over Napoleon

four years before and the 300th anniversary of the Reformation, condemn conservatism and call for German unity

under the motto "Honour - Freedom - Fatherland". Speakers at the event included Heinrich Hermann Riemann, a

veteran of the Lützow Free Corps, the philosophy student Ludwig Rödiger, and Hans Ferdinand Massmann. This

event and a similar gathering at Wartburg during the Revolutions of 1848 are considered seminal moments in the

movement for German unification.

During the rule of the House of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, Grand Duke Karl Alexander ordered the reconstruction of

Wartburg in 1838. The lead architect was Hugo von Ritgen, for whom it became a life's work. In fact, it was

finished only a year after his death in 1889. Drawing on a suggestion by Goethe that the Wartburg would serve

well as a museum, Maria Pavlovna and her son Karl Alexander also founded the art collection (Kunstkammer) that

became the nucleus of today's museum. The reign of the House of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach ended in the German

Revolution in 1918. In 1922, the Wartburg Stiftung (Wartburg Foundation) was established to ensure the castle's

maintenance.

After the end of the Second World War, Soviet occupation forces took the renowned collection of weapons and

armour. Its whereabouts still remain unknown. The Rüstkammer (armoury) of the Wartburg once contained a

notable collection of about 800 pieces, from the splendid armour of King Henry II of France, to the items of

Frederick the Wise, Pope Julius II and Bernhard von Weimar. All these objects were taken by the Soviet

Occupation Army in 1946 and have disappeared in Russia. Two helmets, two swords, a prince's and a boy's

armour, however, were found in a temporary store at the time and a few pieces were given back by the USSR

in the 1960s. The new Russian Government has been petitioned to help locate the missing treasures.

Under communist rule during the time of the GDR extensive reconstruction took place in 1952-54. In particular,

much of the palas was restored to its original Romanesque style. A new stairway was erected next to the palas.

In 1967, the castle was the site of celebrations of the GDR's national jubilee, the 900th anniversary of the Wartburg's foundation, the 450th anniversary of the beginning of Luther's Reformation and the 150th anniversary of the

Wartburg Festival. In 1983, it was the central point of the celebrations on account of the 500th birthday of Martin

Luther. The largest structure of the Wartburg is the Palas, originally built in late Romanesque style between 1157

and 1170. It is considered the best-preserved non-ecclesial Romanesque building north of the Alps. (Wikipedia)

(Author Photo)

Burg Gleichen, Thuringia, Germany. Gleichen Castle owes its fame to the legend of the bigamous Count von Gleichen,

who returned home from the Crusades with a second wife. The three castles known collectively as the "Drei Gleichen"

are Gleichen Castle, Mühlburg Castle and Wachsenburg Castle. They are approx. 20 km from Erfurt in the Drei

Gleichen conservation area.

Burg Gleichen, the Wanderslebener Gleiche (1221 ft. above sea level), was besieged unsuccessfully by the emperor

Henry IVin 1088. It was the seat of a line of counts, one of whom, Ernest III, a crusader, is the subject of a romantic

legend. Having been captured, he was released from his imprisonment by a Turkish woman, who returned with him

to Germany and became his wife, a papal dispensation allowing him to live with two wives at the same time. After

belonging to the elector of Mainz the castle became the property of Prussia in 1803.

(Zerbie Photo)

Burg Gleichen, aerial view.

(Author Photo)

Burg Muhlberg, Thuringia, Germany. Mühlburg (1309 ft. above sea level), the second castle of the Drei Gleichen

group, existed as early as 704 and was besieged by Henry IV in 1087. It came into the hands of Prussia in 1803.

(CTHOE Photo)

Veste Wachsenburg (1358 ft.), the third castle of the Drei Gleichen group, was still inhabited in 1911 and contained a

collection of weapons and pictures belonging to its owner, the duke of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, whose family obtained

possession of it in 1368. It was built about 935. The castle was extensively rebuilt in the 17th and 19th century. The

well-preserved castle (most recently restored in the 1990s) now houses a museum, a hotel and a restaurant. It was built

by Hersfeld Monastery. The castle stand on a hill approximately 93 meters high. In 1441 a notorious robber baron took

control of the castle and made it his base for his raids on the merchants of Erfurt.

(Author's artwork)

Burg Hohenzollern, Germany. Oil on canvas, 18 X 24.

(A. Kniesel Photo, 1 Nov 2006)

Burg Hohenzollern is the ancestral seat of the imperial House of Hohenzollern. It is the third of three castles

built on the site, and is located on top of Mount Hohenzollern, above and south of the town of Hechingen, on the

edge of the Swabian Jura of central Baden-Würtemberg, Germany.

The first castle on the mountain was constructed in the early 11th century. Over the years the House of Hohenzollern

split several times, but the castle remained with the branch of the family, that later acquired its own imperial throne.

This castle was completely destroyed in 1423 after a ten-month siege by the free imperial cities of Swabia.

The second castle, a larger and sturdier structure, was constructed from 1454 to 1461, which served as a refuge for

the Catholic Swabian Hohenzollerns, including during the Thirty Year's War. By the end of the 18th century it was

thought to have lost its strategic importance and gradually fell into disrepair, leading to the demolition of several

dilapidated buildings.

The third, and current, castle was built between 1846 and 1867 as a family memorial by Hohenzollern King Frederick

William IV of Prussia. No member of the Hohenzollern family was in permanent or regular residence when it was

completed, and none of the three German Emperors of the late 19th and early 20th century German Empire occupied

the castle; in 1945 it briefly became the home of the former Crown Prince Wilhelm of Germany, son of the last

Hohenzollern monarch, Kaiser Wilhelm II.

(Author's artwork)

Heidelberger Schloss, as it might have looked before its destruction. Oil on canvas, 11 X 14.

(Pumuckel42 Photo)

Schloss Heidelberg, Germany, as it appears now (Heidelberg-Schloß, 1 May 2005).

Many Canadians with the Canadian Forces and their families lived in Heidelberg, while their military members

served with the Allied Air Forces Central Europe (AAFCE), which was the NATO command tasked with air and

air defence operations in NATO's Allied Forces Central Europe (AFCENT) area of command. AAFCE had initially

been activated on 2 April 1951 at Fontainebleau, France through General Dwight D. Eisenhower's General Order No. 1.

AAFCE consisted of two allied tactical air forces, Second Tactical Air Force, comprising British-Dutch No. 2 Group,

RAF, Belgian-Dutch 69 Group, and British-Belgian No. 83 Group, RAF. Fourth Allied Tactical Air Force,

comprised of the Twelfth Air Force, French 1er Air Division, and No. Canadian Air Division, RCAF. The

peacetime headquarters of 4 ATAF was in Heidelberg, which is why many Canadians served there.

Schloss Heidelberg is a ruin in Germany and landmark of the city of Heidelberg. Heidelberg

was first mentioned in 1196 as "Heidelberch". The castle ruins are among the most important Renaissance structures

north of the Alps. The castle has only been partially rebuilt since its demolition in the 17th and 18th centuries. It is

located 80 metres (260 ft) up the northern part of the Konigstuhl ,hillside, and thereby dominates the view of the

old town. The earliest castle structure near this site was built before 1214 and later expanded into two castles c1294;

however, in 1537, a lightning bolt destroyed the upper castle. The present structures had been expanded by 1650,

before damage by later wars and fires. In 1764, another lightning bolt caused a fire which destroyed some rebuilt sections.

When Ruprecht became the King of Germany in 1401, the castle was so small that on his return from his coronation,

he had to camp out in the Augustinians' monastery, on the site of today's University Square. What he desired was

more space for his entourage and court and to impress his guests, but also additional defences to turn the castle into

a fortress. After Ruprecht's death in 1410, his land was divided between his four sons.

During the reign of Louis V, Elector Palatine (1508–1544) that Martin Luther came to Heidelberg to defend one

of his theses (Heidelberg Disputation) and paid a visit to the castle. He was shown around by Louis's younger

brother, Wolfgang, Count Palatine, and in a letter to his friend George Spalatin praised the castle's beauty and its defences.

In 1618, Protestants rebelling against the Holy Roman Empire offered the crown of Bohemia to Frederick V, Elector

Palatine, who accepted despite misgivings and in doing so triggered the outbreak of the Thirty Year's War. The

Thirty Years' War was a religious war fought primarily in Central Europe between 1618 and 1648. It resulted in

the deaths of over 8 million people, including 20% of the German population, making it one of the most destructive

conflicts in human history.

It was during the Thirty Years War that arms were raised against the castle for the first time. This period marks the

end of the castle's construction; the centuries to follow brought with them destruction and rebuilding.

After his defeat at the Battle of White Mountain on 8 November 1620, Frederick V was on the run as an outlaw

and had to release his troops prematurely, leaving the Palatinate undefended against General Tilly, the supreme

commander of the Imperial and Holy Roman Empire's troops. On 26 August 1622, Tilly commenced his attack

on Heidelberg, taking the town on 16 September, and the castle few days later.

When the Swedes captured Heidelberg on 5 May 1633 and opened fire on the castle from the Königstuhl hill

behind it, Tilly handed over the castle. The following year, the emperor's troops tried to recapture the castle, but it

was not until July 1635 that they succeeded. It remained in their possession until the Peace of Westphalia ending

the Thirty Years War was signed. The new ruler, Chalres Louis (Karl Ludwig) and his family did not move into

the ruined castle until 7 October 1649.

Schloss Heidelberg on the Neckar River showing the Alte Bruecke (Old Bridge), Heilgigeistkirche (Church of the

Holy Ghost), from a 1643 engraving by Matthäus Merian.

After the death of Charles II, Elector Palatine, Louis XIV of France demanded the surrender of the allodial title in

favour of the Duchess of Orléans, Elizabeth Charlotte, Princess Palatine, who he claimed was the rightful heir to

the Simmern lands. On 29 September 1688, the French troops marched into the Palatinate of the Rhine and on 24

October moved into Heidelberg, which had been deserted by Philipp Wilhelm, the new Elector Palatine. At war

against the allied European powers, France's war council decided to destroy all fortifications and to lay waste to

the Palatinate (Brûlez le Palatinat!), in order to prevent an enemy attack from this area. As the French withdrew

from the castle on 2 March 1689, they set fire to it and blew the front off the Fat Tower. Portions of the town were

also burned, but the mercy of a French general, René de Froulay de Tessé, who told the townspeople to set small

fires in their homes to create smoke and the illusion of burning prevented wider destruction.

Immediately upon his accession in 1690, Johann Wilhelm, Elector palatine had the walls and towers rebuilt. When

the French again reached the gates of Heidelberg in 1691 and 1692, the town's defenses were so good that they did

not gain entry. On 18 May 1693, the French were yet again at the town's gates and took it on 22 May. However,

they did not attain control of the castle and destroyed the town in attempt to weaken the castle's main support base.

The castle's occupants capitulated the next day. The French then took the opportunity to finish the destruction of

Heidelberg that they began in 1689, after their hurried exit from the town. The towers and walls that had survived

the last wave of destruction, were blown up with mines.

In 1697 the Treaty of Ryswick was signed, marking the end of the War of the Grand Alliance and finally bringing

peace to the town. Plans were made to pull down the castle and to reuse parts of it for a new palace in the valley.

When difficulties with this plan became apparent, the castle was partially repaired. In the following decades, basic

repairs were made, but Heidelberg Castle remained essentially a ruin. In 1767, the south wall was quarried for

stone to build Schwetzingen Castle. In 1784, the vaults in the Ottoheinrich wing were filled in, and the castle

used as a source of building materials.

The question of whether the castle should be completely restored was discussed for a long time. Eventually, a

detailed plan was developed for preserving or repairing the main building. The planners completed their work

in 1890, which led a commission of specialists from across Germany to decide that while a complete or partial

rebuilding of the castle was not possible, it was possible to preserve it in its current condition. Only the Friedrich

Building, whose interiors were fire damaged, but not ruined, would be restored. This reconstruction was done

from 1897 to 1900 by Karl Schäfer at the enormous cost of 520,000 Marks.

The forecourt is the area enclosed between the main gate, the upper prince's well, the Elisabeth gate, the castle

gate and the entrance to the garden. Around 1800 it was used by the overseer for drying laundry. Later on, it was

used for grazing cattle, and chickens and geese were kept here. The approach to the forecourt takes you across a

stone bridge, over a partially filled-in ditch. The main gate was built in 1528. The original watchhouse was

destroyed in the War of the Grand Alliance, and replaced in 1718 by a round-arched entrance gate. The gate to

the left of the main entrance was closed by means of a drawbridge. The former harness room, originally a coach

house, was in reality begun as a fortification. After the Thirty Year's War, it was used as a stables as well as a

toolshed, garage and carriage house. (Harry B. Davis: "What Happened in Heidelberg: From Heidelberg Man to

the Present": Verlag Brausdruck GmbH, 1977)

(Storfix Photo, 16 Oct 2005)

Coburg: Veste Coburg (Fortress Coburg), is one of the most well-preserved medieval fortresses of Germany. It is situated

on a hill above the town of Coburg, in the Upper Franconia region of Bavaria. Veste Coburg dominates the town

of Coburg on Bavaria's border with Thuringia. It is located at an altitude of 464 meters above sea level, 167 meters

above the town. Its size (around 135 meters by 260 meters) makes it one of the medium sized fortresses in Germany.

The hill on which Veste Coburg stands was inhabited from the Neolithic to the early Middle Ages according to the

results of excavations. The first documentary mention of Coburg occurs in 1056, in a gift by Richeza of Lotharingia.

Richeza gave her properties to Anno II, Archbishop of Cologne, to allow the creation of Saalfeld Abbey in 1071.

In 1075, a chapel dedicated to Saint Peter and Saint Paul is mentioned on the fortified Coberg. This document also

refers to a Vogt named Gerhart, implying that the local possessions of the Saalfeld Benedictines were administered

from the hill.

A document signed by Pope Honorius II in 1206 refers to a mons coburg, a hill settlement. In the 13th century, the

hill overlooked the town of Trufalistat (Coburg's predecessor) and the important trade route from Nuremberg via

Erfurt to Leipzig. A document dated from 1225 uses the term sloss (palace) for the first time. At the time, the

town was controlled by the Dukes of Merania (or Meran). They were followed in 1248 by the Counts of Henneberg,

who ruled Coburg until 1353, save for a period from 1292-1312, when the House of Ascania (Askanien) was in charge.

In 1353, Coburg fell to Friedrich, Markgraf von Meißen of the House of Wettin. His successor, Friedrich der

Streitbare, was awarded the status of Elector of Saxony in 1423. Thus, Coburg – despite being in Franconia – was

now referred to as "Saxony", like other properties of the House of Wettin. As a result of the Hussite Wars, the

fortifications of the Veste were expanded in 1430.

In 1485, in the Partition of Leipzig, Veste Coburg fell to the Ernestine branch of the family. A year later, Elector

Friedrich der Weise and Johann der Beständige took over the rule of Coburg. Johann used the fortress as a

residence from 1499. In 1506/07, Lucas Cranach the Elder, lived and worked in the Fortress. From April to

October 1530, during the Diet of Augsburg, Martin Luther sought protection at the Fortress, as he was under

an Imperial ban at the time. During his stay at the fortress, Luther continued with his work translating the Bible

into German. In 1547, Johann Ernst moved the residence of the ducal family to a more convenient and fashionable

location, Ehrenburg Palace in the town center of Coburg. The Veste then served as a fortification only.

In the further splitting of the Ernestine line, Coburg became the seat of the Herzogtum von Sachsen-Coburg, the

Duchy of Saxe-Coburg. The first duke was Johann Casimir (1564-1633), who modernized the fortifications. In

1632, the fortress was unsuccessfully besieged by Imperial and Bavarian forces commanded by Albrecht von

Wallenstein for seven days during the Thirty Years' War. Its defence was commanded by Georg Christoph von

Taupadel. On 17 March 1635, after a renewed siege of five months' duration, the Veste was handed over to the

Imperials under Guillaume de Lamboy.

From 1638 to 1672, Coburg and the fortress were part of the Duchy of Saxe-Altenburg. In 1672, they passed to

the Dukes of Saxe-Gotha, and in 1735 it was joined to the Duchy of Saxe-Saalfeld. Following the introduction of Primogeniture by Duke Franz Josias (1697-1764), Coburg went by way of Ernst Friedrich (1724-1800) to

France (1750-1806), noted art collector, and to Duke Ernst III (1784-1844), who remodeled the castle.

In 1826, the Duchy of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha was created and Ernst now styled himself "Ernst I". Military use of

the fortress had ceased by 1700 and outer fortifications had been demolished in 1803-38. From 1838-60, Ernst

had the run-down fortress converted into a Gothic revival residence. In 1860, use of the Zeughaus as a prison

(since 1782) was discontinued. Through a successful policy of political marriages, the House of Saxe-Coburg and

Gotha established links with several of the major European dynasties, including that of the United Kingdom.

The dynasty ended with the reign of Herzog Carl Eduard (1884-1954), also known as Charles Edward, Duke of

Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, a grandson of Queen Victoria, who until 1919 also was the 2nd Duke of Albany in the

United Kingdom. Under his rule, many changes made to the Veste Coburg in the 19th century were reversed

under architect Bodo Ebhardt, with the aim of restoring a more authentic medieval look. Along with the other

ruling princes of Germany, Carl Eduard was deposed in the revolutions of 1918-1919. After Carl Eduard abdicated

in late 1918, the fortress came into possession of the state of Bavaria, but the former duke was allowed to live there

until his death. The works of art collected by the family were gifted to the Coburger Landesstiftung, a foundation,

which today runs the museum (see below.

In 1945, the fortress was seriously damaged by artillery fire in the final days of the Second World War. After 1946,

renovation works were undertaken by the new owner, the Bavarian Administration of State-owned Palaces,

Gardens and Lakes.

Veste Coburg is open to the public and today houses museums, including a collection of art objects and paintings

that belonged to the ducal family of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, a large collection of arms and armor, significant

examples of early modern coaches and sleighs, and important collections of prints, drawings and coins. (Daniel

Burger: Festungen in Bayern. Schnell + Steiner, Regensburg 2008)

(Störfix Photo)

Veste Coburg.

(Presse03 Photo)

Veste Coburg, aerial view.

(GZagatta Photo)

Mechernich: Burg Satzvey is a medieval moated castle, originally built in the 12th century, located on the

northeastern edge of the Eifel in Mechernich (district Satzvey) in Euskirchen, North Rhine-Westphalia. It is one

of the best preserved moated castles in the Rhineland, retaining much of its original Rhenish structure. It was built

by the ministerial nobility of the 14th and 15th centuries in the lowland (high nobility tended to build hilltop castles

that were difficult to conquer). Without mountains to build on as a natural obstacle for attackers, lowland castle

builders had to rely on moats and water ditches that were difficult to overcome. For this reason, moated castles

were usually built on two islands and were almost always near a stream that supplied the trenches with water. The

more strongly fortified main castle was thereby additionally protected by an outer castle built on a second island.

Satzvey castle was originally built on two islands surrounded by moats.

In the 12th century, Satzvey castle was held by the Hofanlage family, who had named it after the river flowing

through the Veybach field. The Archbishop of Cologne, Engelbert II von der Mark, gave Satzvey as a fief to Otto

von Vey, who was mentioned in a document in 1368 as the first Vogt of this name. When his male line died out,

his granddaughter brought her husband Heinrich von Krauthausen to the castle in 1391. In 1396, Heinrich built

the first originally free-standing, two-story Gothic castle to serve as the new administrative seat.

In the 15th century, the fortification of the facility was increased. The gatehouse with the twin towers was built,

a kennel was built and the outer bailey was reinforced. In the second half of the 15th century the castle belonged

to the von Meller family, after 1512 it was owned by various noble families until it was taken over by Wilhelm

von Büllesheim in 1561. The Archbishop of Cologne supported the appropriation to maintain peace in the country.

In 1578 the Duke of Jülich, Wilhelm V the Rich, occupied the castle. After three years the lord of the castle Spies

von Büllesheim, pledged his oath of allegiance to both the sovereign of Jülich and the sovereign of Cologne,

Archbishop Gebhard I von Waldburg.

At the end of the 16th century the bailiwick became the imperial seat of power. In 1747, Johann Spies von

Büllesheim sold the castle to Karl Otto von Gymnich, placeing it in the possession of the Rhenish noble family

von und zu Gymnich. In 1794, the subordinate rule of Satzvey was lost and from then on only had the status of

a manor suitable for the state assembly. In 1882 the moated castle passed to the Imperial Count Dietrich

Wolff-Metternich after the Gymnich died out.

Prior to 1882, there had been no major structural changes at Satzvey Castle since the 16th century. Under Dietrich

Wolff-Metternich, extensive renovations and extensions were made the castle. Moats were drained, the castle

house was expanded with porches and extensions and new towers were built. Buildings in the style of English

stables were built on the former outer bailey, and an estate with farm buildings was added. The core and these

construction measures was the existing original structure from the early 15th century.

For centuries, the castle was largely spared from military destruction. However , it was badly damaged in the

Second World War. In 1942, Countess Adeline Wolff Metternich zur Gracht (1919-2010) took over the inheritance

after her brother Dietrich, died in the war. In 1944 she married Franz Josef Count Beissel von Gymnich zu Frens

(1916–2008), a younger branch of the von and zu Gymnich family. Satzvey Castle was passed to Count Beissel

von Gymnich. The young couple moved into the castle and repaired the most important components in the

following years. Their four sons were born here. The couple now live in Bad Münsteifel.

In 1977 the parents transferred the property to their eldest son, Count Franz Josef Beissel von Gymnich. In order

to be able to preserve the castle and to preserve the history and traditions of bygone eras, he decided to make the

complex accessible to the public and organized the historical knight festival there together with his wife Jeannette

and his daughter.

Satzvey Castle is a well-preserved moated castle. The original castle house, the two-tower gatehouse, the north

wall and the north tower are the oldest components. They have survived for 600 years and, together with the

construction work of the late 19th century, form a typical German moated castle. On 19 April 2020, the attached

castle bakery burned down. (Elke Lutterbach: Burg Satzvey guide, reference work and picture book ( knight castles.

Volume 2). JP Bachem-Verlag, Cologne 2005)

(Charlie1965nrw Photo)

Burg Satzvey, main house.

(Dguendel Photo)

Burg Satzvey, gate house.

(Alf van Beem Photo)

Burg Satzvey.

(ElizabethMargit Photo)

Schloss Braunfels, is a stately home that had been built from a castle built in the 13th century by the Counts of Nassau.

From c1260, the castle served as the Solms-Braunfels noble family's residential castle. After Solms Castle was destroyed

by the Rhenish League of Towns in 1384, Braunfels Castle became the seat of the Counts of Solms. Over the castle's

more than 750-year-long history, building work was done many times. Particularly worthy of mention is the town and

castle fire of 1679, which burnt much of Braunfels and its stately seat down. Both were then built into a Baroque

residence. Braunfels Castle was rebuilt out of materials that were still on hand.

Schloss Braunfels as it appeared in 1655. Matthäus Merian.

(Ulrich Mayring Photo)

Schloss Braunfels.

(I, ArtMechanic Photo, 22 June 2005)

Schloss Braunfels.

(R. Wallenstein Photo, 29 Jan 2006)

Anweiler: Reichsburg Trifels, first mentioned in documents dated 1081. This castle was designated as a

secure site for preserving the Imperial Regalia of the Hohenstaufen Emperors until they were moved to Walburg

Caste in Swabia in 1220. Richard the Lionheart, King of England was kept a prisoner here, after he was captured

by Duke Leopold V of Austria near Vienna in Dec 1192 as he was returning from the Third Crusade. He was

handed over to Emperor Henry VI of Hohenstaufen and his period of captivity from 31 March to 19 April 1193 is

well documented. Our family visited this castle often during our postings to Germany. Its a steep climb.

Reichsburg Trifels was one of many castles our family visited over the years, and in fact, it was the very first for me

on Saturday, 27 June 1959.

(jens@storchenhof-pap…Photo)

Singen: Festung Hohentwiel (Fortress Hohentwiel) is a ruin standing on top of Hohentwiel mountain (an extinct

volcano). It was built in 914 using stone taken from the mountain by Burchard II, Duke of Swabia. Originally,

the Monastery of St. Georg stood was within the fortress, but in 1005 it was moved to Stein am Rhein (now in

Switzlerland), and the Swabian dukes lost control of Hohentwiel. In the later Middle Ages the noble families

von Singen-Twiel (12th–13th centuries), von Klingen (to 1300) and von Klingenberg (to 1521) resided here. In

1521, it was passed on to Duke Ulrich von Württemberg, who developed Hohentwiel into one of the strongest

fortresses of his duchy. During this time, it began to be used as a prison, and in 1526, Hams Müller von Bulgenbach,

a peasant commander, was imprisoned there before he was executed.

The fortress resisted five Imperial sieges sieges in the Thirty Years' War, under the command of Konrad Widerholt

between 1634 and 1648. The effect was that Württemberg remained Protestant, while most of the surrounding areas

returned to Catholicism in the Counterreformation. The castle served as a Württemberg prison in the 18th century

and was destroyed in 1800 after being peacefully handed over by the French. Today the former fortress Hohentwiel

is the largest castle ruin in Germany. The modern city of Singen nestles at the foot of the mountain.

Festung Hohentwiel, 1643, Merian illustration.

(Frank Vincentz Photo)

Festung Hohentwiel.

(Hansueli Krapf Photo)

Festung Hohentwiel, aerial view.

(Frank Vincentz Photo)

Festung Hohentwiel.

(Gladys80 Photo)

Festung Hohentwiel.

Siege of Festung Hohentwiel, 1641.

Blockade of Festung Hohentwiel, 1644.

Festung Hohentwiel, 1692.

Festung Hohentwiel, ground plan, 1735.

(Peter Stein Photo)

Festung Hohentwiel, aerial view.

(Heribert Pohl Photo)

Neuffen: Burg Hohenneuffen is a large hill fort now in ruins, standing above the town of Neuffen in the district of

Esslingen in Baden-Württemberg. The high medieval castle ruins are located east of Neuffen at 745.4 m above

sea level on "fortress mountain", a white Jurassic rock on the edge of the Swabian Alb. The castle guards a

strategically favorable location on the Albantrauf.

The Hohenneuffen was already settled in ancient times. In the late Celtic La Tène period (450 to 1 BC) it served as

an outpost of the well-known Heidengraben -oppidum (Celtic fort c1 BC), which included the entire

"Erkenbrechtsweiler peninsula" of the Swabian Alb. The origin of the name (1206 Niffen ) is controversial. On the

one hand, it is traced back to a Celtic word * Nîpen and then interpreted as a " battle castle ". Another etymology

derives the name of the other hand Germanic * hnîpa meaning "steep slope, mountainside".

The castle was built between 1100 and 1120 by Mangold von Sulmetingen, who later called himself von Neuffen.

The first mention of the castel is found in a document dated 1198, indicating that at that time it was owned by the

noble free von Neuffen family, to which the minstrel Gottfried von Neifen belonged. At the end of the 13th century

the castle went to the Lords of Weinsberg, who sold it to the House of Württemberg in 1301. In 1312, the castle

proved its ability to defend itself in the internal conflicts of the Holy Roman Empire (the Imperial War),

demonstrating that it could not be taken.

The expansion of the Hohenneuffen into a state fortress began as early as the 15th century. The decisive building

measures for the fortified complex were not undertaken by Duke Ulrich until the middle of the 16th century. The

outer works, round towers, bastions, a commandant's office, casemates, stables the armoury and two cisterns were

built. The fotification thus created existed for two centuries without any major changes. In 1519, Hohenneufen

was forced to surrender to the Swabian Federation. In the German Peasant Wars in from 1524, it could not be taken

again.

The Hohenneuffen was besieged for more than a year during the Thirty Years' War. In November, the fortress

commander, Captain Johann Philipp Schnurm, and the troubled crew decided to negotiate a surrender with the

enemy, which provided for a free withdrawal with weapons and all belongings. On 22 November 1635, Schnurm

handed the fortress over to the imperial troops after a 15-month siege. Contrary to the promises made, the team

was forced to serve in the imperial army, and Schnurm lost his property.

A legend, which does not correspond to the historical events, says the following: The people at the castle gave

their donkeys the last grain that they had left, slaughtered it and threw the filled stomach of the animal into the

camp of the enemy. Because they believed that the besieged still had enough supplies, they lost patience and

moved away. Since then, the donkey has been the “mascot” of the city of Neuffen.

The Württemberg Duke Karl Alexander planned to develop the Hohenneuffen into a fortress based on the French

model in the 18th century; but he died before completion. His successor Carl Eugen abandoned the plan in view

of the high costs and dubious military benefits. In 1793 plans were made to raze the fortress and the remains were

to be sold for use as building materials. These plans were approved, and from 1795 it was no longer used. It was

finally released for demolition in 1801, which began in 1803. The residents of the area were happy about having

access to cheap building material. It was not until 1830 that they began to secure the remains, and in the 1860s

the ruins were made accessible to the public. In 1862 a restaurant was set up in the building in the upper courtyard.

Like other fortresses, the Hohenneuffen served at times as a state prison, where important prisoners were arrested

and, if necessary, tortured. The fates of some are known. A young Count von Helfenstein, Friedrich, fell to his

death in 1502 while attempting to escape. In 1512 Duke Ulrich had the abbot of the Zwiefalten monastery, Georg

Fischer, detained here. The elderly Tübingen Vogt Konrad Breuning was also subjected to the prince's arbitrariness

in 1517 and was beheaded after imprisonment and torture in Stuttgart. In the 17th century, Mattäus Enzlin, Duke

Friedrich's Chancellor, suffered a similar fate. In 1737 Joseph Suss became Oppenheimer, the Jewish court factor

and personal financial advisor to Duke Karl Alexander. Joseph was imprisoned in the Hohenneuffen for a few

weeks before he was transferred to the Hohenasperg fortress and executed in 1738, as a victim of judicial murder

at the gates of Stuttgart.

During the Second World War, the Hohenneuffen was an air station. The military governments of the zones of

occupation founded the states of Württemberg-Baden in the American zone in 1945/46 and Württemberg-

Hohenzollern and Baden (although it only included the southern part of the country) in the French zone. When it

became clear in 1948 that a constitution was being drawn up for western Germany, some politicians took the

initiative; they wanted the countries in the south-west to merge. The head of government of Württemberg-Baden,

Reinhold Maier, invited the governments of the three countries to a conference on 2 August 1948, which took

place in the Hohenneuffen. He wanted to make a first approximation. A delegation led by Leo Wohleb, who was

an uncompromising advocate for the restoration of the state of Baden. Württemberg-Hohenzollern was represented

by its Interior Minister Viktor Renner. The delegations included ministers, party leaders, MPs and officials from the

three countries.

The venue was chosen with care. The wide view of the country and, above all, the drastic zone boundary between

the districts of Reutlingen and Nürtingen, a few kilometers away, is impressive. Separated from their governments

and the public, the participants wanted to debate objectively, well served with valley wine . In the end, an agreement

did not come about, but the meeting had given impetus and important groundwork had been set. This three-country

conference which took place in the Hohenneuffen thus marks the beginning of the long-term dispute over the

formation of the south-western state of Baden-Württemberg, which was launched in 1952. Today the Hohenneuffen

with its restaurant, beer garden and kiosk is a popular destination. Entry to the castle is free. The casemates, some of

which are accessible, are worth seeing .

The lighting of the outer walls on Sundays and public holidays is also very impressive. The facility, originally

donated by the Neuffen citizen Otto Krieg in the 1950s, was completely renovated in 1984 by the Stadt- und

Kulturring Neuffen eV and is also maintained by the latter. (Walter Bär: The Neuffen, history and stories about the

Hohenneuffen. Published by the city of Neuffen, 1992)

(ufo 709 Photo)

Burg Hohenneufen, aerial view.

(Swabian Tourismusverband Photo)

Burg Hohenneufen, aerial view.

(MFSG Photo)

Burg Hohenneufen, aerial view.

(Aerial video capture Photo)

Burg Hohenneufen, aerial view.

(Genet Photo)

The Heidengraben, a Celtic oppidum (a fortified, urban-like settlement from the La Tène period - late Iron Age),

that dates to the 1st century BC. It was located on the Swasbian Alb near Grabenstetten. The remains of the

fortification of the oppidum are still visible as a rampart. The oppidum had an outer and an inner ring of fortifications,

inside the latter was the settlement called Elsachstadt (after the Elsach brook, which rises below the oppidum in

the Falkensteiner cave).

The oppidum is located on the Grabenstetten peninsula , a part of the Alb plateau that is only connected to the rest

of the Alb plateau by a narrow strip south of Grabenstetten, so that the Alb is a natural fortification. This location

made it possible to enclose an area of around 16.6 km² by building four short fortifications. These fortifications

separated the present day area of the municipality of Hülben, the Burgwald area between Beurener Fels and Brucker

Fels , the connection to the rest of the Alb plateau and the Lauereck area bordering the inner fortification in the

south. The Elsachstadt settlement had an area of 1.53 km² and was located west of the present day municipality

of Grabenstetten.

Apparently the Grabenstetten peninsula was settled a few centuries before the oppidum was established. There

are graves from around 1000 BC near today's Burrenhof. Some of the burial mounds that can still be seen date

from c500 BC. This may have been the locationof Riusiava, indicatged in the ancient atlas of Ptolemy. Scientific

excavations are continuing. The Heidengraben played a major role in the so-called Celtic concept of the state of

Baden-Württemberg. (The Heidengraben - A Celtic oppidum in the Swabian Alb . Theiss Verlag, 2012)

(Aspirinics Photo)

The tree-covered wall is a remnant of the inner fortification ring on the northern edge of Elsachstadt.

Course of the Heidengraben.

(BKLuis Photo)

Burg Pappenheim (Burg Kalteneck) was the scene of numerous confrontations of the dukes of Bavaria and King Henry Raspe against the imperial forces in the 13th Century. Battles andconflict circled the castle in several waves until the 14th and 15 Century. In 1633, during the Thirty Yearsè War, the castle and town were conquered and destroyed by Swedish regiments. In 1703 during the Spanish war of succession, Pappenheim was again looted, this time by French troops and the castle was partially destroyed after bombardment. During the War of the Spanish Succession, the castle was shelled for two days by French troops, until it was finally captured. Since then the castle has been uninhabited. Pappenheim is a town in the Weißenburg-Gunzenhausen district, in Bavaria, situated on the Altmühl river.

(Tilman2007 Photo)

Burg Pappenheim.

(Dark Avenger Photo)

Burg Pappenheim.

(Derzno Photo)

Burg von Pappenheim.

(Author's artwork)

Schloss Neuschwanstein, Germany. Oil on canvas, 18 X 24.

(Cezary Piwowarski Photo, 1 June 2007)

Hohenschwangau: Schloss Neuschwanstein is a 19th-century Romanesque Revival palace on a rugged hill

above the village of Hohenschwangau, near Füssen in southwest Bavaria, Germany. The palace was commissioned

by King Ludwig II of Bavaria as a retreat and in honour of Richard Wagner. Ludwig paid for the palace out of his

personal fortune and by means of extensive borrowing, rather than Bavarian public funds. The castle was intended

as a home for the King, until he died in 1886. It was open to the public shortly after his death. Since then more

than 61 million people have visited Neuschwanstein Castle. More than 1.3 million people visit annually, with as

many as 6,000 per day in the summer.

The municipality of Schwangau stands at an elevation of 800 m (2,620 ft) at the southwest border of the German

state of Bavaria. Its surroundings are characterised by the transition between the Alpine foothillss in the south

(toward the nearby Austrian border) and a hilly landscape in the north that appears flat by comparison. In the

Middle Ages, three castles overlooked the villages. One was called Schwanstein Castle. In 1832, Ludwig's father

King Maximilian II of Bavaria bought its ruins to replace them with the comfortable neo-Gothic palace known

as Hohenschwangau Castle. Finished in 1837, the palace became his family's summer residence, and his elder

son Ludwig (born 1845) spent a large part of his childhood here.

Vorderhohenschwangau Castle and Hinterhohenschwangau Castle sat on a rugged hill overlooking Schwanstein

Castle, two nearby lakes (Alpsee and Schwansee), and the village. Separated by only a moat, they jointly consisted

of a hall, a keep, and a fortified tower house. In the nineteenth century only ruins remained of the twin medieval

castles, but those of Hinterhohenschwangau served as a lookout place known as Sylphenturm.

The ruins above the family palace were known to the crown prince from his excursions. He first sketched one of

them in his diary in 1859. When the young king came to power in 1864, the construction of a new palace in place

of the two ruined castles became the first in his series of palace building projects. Ludwig called the new palace

New Hohenschwangau Castle; only after his death was it renamed Neuschwanstein. The confusing result is that

Hohenschwangau and Schwanstein have effectively swapped names: Hohenschwangau Castle replaced the ruins

of Schwanstein Castle, and Neuschwanstein Castle replaced the ruins of the two Hohenschwangau Castles.

In a letter to Richard Wagner, Ludwig wrote,

"It is my intention to rebuild the old castle ruin of Hohenschwangau near the Pöllat Gorge in the authentic style

of the old German knights' castles, and I must confess to you that I am looking forward very much to living there

one day [...]; you know the revered guest I would like to accommodate there; the location is one of the most beautiful

to be found, holy and unapproachable, a worthy temple for the divine friend who has brought salvation and true

blessing to the world. It will also remind you of "Tannhäuser" (Singers' Hall with a view of the castle in the

background), "Lohengrin'" (castle courtyard, open corridor, path to the chapel) ..."

(Ludwig II, Letter to Richard Wagner, May 1868)

The building design was drafted by the stage designer Christian Jank, and realised by the architect Eduard Riedel.

For technical reasons, the ruined castles could not be integrated into the plan. The king insisted on a detailed plan

and on personal approval of each and every draft. The palace can be regarded as typical for nineteenth-century

architecture. The shapes of Romanesque (simple geometric figures such as cuboids and semicircular arches),

Gothic (upward-pointing lines, slim towers, delicate embellishments) and Byzantine architecture and art (the

Throne Hall décor) were mingled in an eclectic fashion and supplemented with 19th-century technical achievements.

The palace was primarily built in Romanesque style.

In 1868, the ruins of the medieval twin castles were completely demolished and the remains of the old keep were

blown up. The foundation stone for the palace was laid on 5 September 1869; in 1872 its cellar was completed and

in 1876, everything up to the first floor, the gatehouse being finished first. At the end of 1882 it was completed

and fully furnished, allowing Ludwig to take provisional lodgings there and observe the ongoing construction work.

In 1874, management of the civil works passed from Eduard Riedel to Georg von Dollmann. The topping out

ceremony for the Palas was in 1880, and in 1884, the King was able to move in to the new building. In the same

year, the direction of the project passed to Julius Hofmann, after Dollmann had fallen from the King's favour. The

palace was erected as a conventional brick construction and later encased in various types of rock. The white

limestone used for the fronts came from a nearby quarry.

The sandstone bricks for the portals and bay windows came from Schlaitdorf in Württemberg. Marble from

Untersberg near Salzberg was used for the windows, the arch ribs, the columns and the capitals. The Throne

Hall was a later addition to the plans and required a steel framework. The transport of building materials was

facilitated by scaffolding and a steam crane that lifted the material to the construction site. Another crane was

used at the construction site. The recently founded Dampfkessel-Revisionsverein (Steam Boiler Inspection

Association) regularly inspected both boilers.

For about two decades the construction site was the principal employer in the region. In 1880, about 200 craftsmen

were occupied at the site, not counting suppliers and other persons indirectly involved in the construction. At times

when the King insisted on particularly close deadlines and urgent changes, reportedly up to 300 workers per day

were active, sometimes working at night by the light of oil lamps. Statistics from the years 1879/1880 support an

immense amount of building materials: 465 tonnes (513 short tons) of Salzburg marble, 1,550 t (1,710 short tons)

of sandstone, 400,000 bricks and 2,050 cubic metres (2,680 cu yd) of wood for the scaffolding. In 1870, a society

was founded for insuring the workers, for a low monthly fee, augmented by the King. The heirs of construction

casualties (30 cases are mentioned in the statistics) received a small pension.

In 1884, the King was able to move into the (still unfinished) Palas, and in 1885, he invited his mother Marie to

Neuschwanstein on the occasion of her 60th birthday. By 1886, the external structure of the Palas (hall) was mostly

finished. In the same year, Ludwig had the first, wooden Marienbrücke over the Pöllat Gorge replaced by a steel

construction.

Despite its size, Neuschwanstein did not have space for the royal court, but contained only the King's private

lodging and servants' rooms. The court buildings served decorative, rather than residential purposes: The palace

was intended to serve King Ludwig II as a kind of inhabitable theatrical setting. As a temple of friendship it was

also dedicated to the life and work of Richard Wagner, who died in 1883 before he had set foot in the building.

In the end, Ludwig II lived in the palace for a total of only 172 days.

Neuschwanstein, the symbolic medieval knight's castle, was not King Ludwig II's only huge construction project.

It was followed by the rococo style Lustschloss of Linderhof Palace and the baroque palace of Herrenchiemsee, a

monument to the era of absolutism. Linderhof, the smallest of the projects, was finished in 1886, and the other two

remain incomplete. All three projects together drained his resources. The King paid for his construction projects by

private means and from his civil list income. Contrary to frequent claims, the Bavarian treasury was not directly

burdened by his buildings. From 1871, Ludwig had an additional secret income in return for a political favour given

to Otto von Bismarck.

Neuschwanstein was still incomplete when Ludwig II died in 1886. The King never intended to make the palace

accessible to the public. No more than six weeks after the King's death, however, the Prince-Regent Luitpold,

ordered the palace opened to paying visitors. The administrators of King Ludwig's estate managed to balance the

construction debts by 1899. From then until the First World War, Neuschwanstein was a stable and lucrative source

of revenue for the House of Wittelsbach, indeed King Ludwig's castles were probably the single largest income s

ource earned by the Bavarian royal family in the last years prior to 1914. To guarantee a smooth course of visits,

some rooms and the court buildings were finished first. Initially the visitors were allowed to move freely in the

palace, causing the furniture to wear quickly.

When Bavaria became a republic in 1918, the government socialised the civil list. The resulting dispute with the

House of Wittelsbach led to a split in 1923: King Ludwig's palaces including Neuschwanstein fell to the state and

are now managed by the Bavarian Palace Department, a division of the Bavarian finance ministry. Nearby

Hohenschwangau Castle fell to the Wittelsbacher Ausgleichsfonds, whose revenues go to the House of Wittelsbach.

The visitor numbers continued to rise, reaching 200,000 in 1939.

Due to its secluded location, the palace survived the destruction of two World Wars. Until 1944, it served as a

depot for Nazi pluner that was taken from France by the Reichsleiter Rosenberg Institute for the Occupied Territories

(Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg für die besetzten Gebiete), a suborganisation of the Nazi Party. The castle

was used to catalogue the works of arts. After the end of the Second World War, 39 photo albums were found in

the palace documenting the scale of the art seizures. The albums are now stored in the United States National Archives.

In April 1945, the SS considered blowing up the palace to prevent the building itself and the artwork it contained f

rom falling to the enemy. The plan was not carried out, and at the end of the war the palace was surrendered

undamaged to representatives of the Allied forces. Thereafter the Bavarian archives used some of the rooms as a

provisional store for salvaged archivalia, as the premises in Munich had been bombed. (Ammon, Thomas (2007),

Ludwig II. für Dummies: Der Märchenkönig—Zwischen Wahn, Wagner und Neuschwanstein, Wiley-VCH)

(Taxiarchos228 Photo)

Schloss Neuschwanstein, inner court.

(Zeppelubil Photo)

Schloss Neuschwanstein.

(Woffka rus Photo)

Hohenschwangau: Schloss Hohenschwangau is located directly across from Schloss Neuschwanstein, above the village of

Hohenschwangau in the municipality Schwangau in Fussen, Bavaria. A "Castrum Swangowe" was first mentioned

in a document in 1090. This referred to a pair castles, the Vorder and Hinterschwangau, the ruins of which stood

on the site until Neuschwanstein was built. The Lords of Schwangau lived on this double castle as ministerials of

the Welfs. When Welf VI died in 1191 the Guelph property in Swabia fell to the Staufer family. After the death

of Konradin in 1268, the land went to the empire. The Knights of Schwangau then continued to rule over it as an

imperial fied until they in turn died out in 1536.

When Duke Rudolf IV of Austria brought Tyrol under Habsburg rule in 1363, Stephan von Schwangau and his

brothers committed their fortresses Vorder and Hinterschwangau to his rule, along with the Frauenstein Castle.

They also promised to keep the Sinwellenurn open to the Austrian duke. A document from 1397 mentions the

Schwanstein, today's Hohenschwangau Castle, for the first time. It was less fortified but easier to reach, and was

built below the older double castle on a hill above the Alpsee.

After Ulrich von Schwangau had divided his rule over his four sons in 1428, the once proud family of the Lords of

Schwangau experienced a steady downward trend. Mismanagement and inheritance disputes led Georg von

Schwangau to sell his inheritance, the Hohenschwangau castles and the Frauenstein, in 1440 to Duke Albrecht III.

It was later sold to Bayern-Munich, although the Schwangau residents remained on site, maintaining the castle for

the Dukes of Bavaria. In 1521 the two brothers Heinrich and Georg von Schwangau were again enfeoffed with

their property by Emperor Charles V at the Reichstag in Worms, but in 1535 they were forced to sell it to the

Imperial Councilor Wolf for 35,000 florins. Both brothers died in 1536, the last of their line.

Johann Paumgartner was adviser and financier of the emperor Charles V, who ennobled him to imperial baron in

1537, after which he called himself Paumgartner von Hohenschwangau zum Schwanstein. He had the neglected

Schwanstein Castle restored by Italian craftsmen as the center of his new rule, while Vorder and

Hinterhohenschwangau and Frauenstein continued to fall into disrepair. The architect Lucio di Spazzi, who

worked at the Innsbruck Hofburg, used the existing building fabric, kept the outer walls with crenellated crowns

and towers, but redesigned the interior for contemporary living requirements, creating the current floor plan with

the regular grouping of three suites of rooms on both sides of a continuous central fleece, which is identical on all

floors. He put a ring of bastions around the residential building. In 1547 the construction work was completed.

In 1549 Paumgartner died and the rule fell to his two sons David and Georg, who got into debt. In 1561 David

Paumgartner pledged the imperial rule to Margrave Georg-Friedrich of Brandenburg-Ansbach-Kulmbach, who

sold it to Duke Albrecht V of Bavaria in 1567. The sale also brought with it the claims of Paumgartner's creditors

and as a result, the castle was enfeoffed with Hohenschwangau under imperial law. In 1604 Duke Max I of

Bavaria was alloted the entitlement to the imperial fiefs associated with Hohenschwangau. In 1670 the castle

went to Elector Ferdinand Maria of Bavaria.

The castle went to the later sons of the Wittelsbach electors. Whe the Thirty Years' War, came, the castle began

to fall into disrepair again. In 1743, during the War of the Austrian Succession, it was plundered by the Austrians.

It was later repaired by the court building department as the seat of the nursing court. After the new office building

was built in 1786, it fell into disrepair again. It was not until 1803 that the Hohenschwangau Reichslehen was

incorporated into the Electorate of Bavaria through the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss, which rose to become the

Kingdom of Bavaria in 1805. During the coalition wars, from 1800 to 1809, the castle came under a brief but

unsuccessful bombardment and siege by the French. Later, the castle was used as a barracks for French and Austrian

troops. In 1820, under King Maximilian I, the castle was sold for demolition for 200 guilders. Prince Ludwig

von Oettingen-Wallerstein, whose family had owned the Sankt Mang monastery in nearby Füssen since 1802,

heard of the intended destruction in 1821 and bought the castle for 225 guilders to save it. He was enthusiastic

about the location of the castle, situated in its charming landscape. The prince had repairs carried out on the castle,

but sold it in 1823. Johann Adolph Sommer, the next owner, intended to set up a flax spinning mill in the castle,

but this did not happen.

King Ludwig I gave his son, Crown Prince Maximilian, the Hohenfüssen Castle, which had been the former

summer residence of the Augsburg bishops. After visiting Füssen in 1829 the Crown Prince Hohenfüssen and,

after three years of purchase negotiations, acquired Schwanstein Castle in 1832, which he re-named Hohenschwangau

Castle. Crown Prince Max had the palace rebuilt in neo-Gothic style up to 1837. In 1842 the Crown Prince married Princess Marie of Prussia, whereupon new rooms and outbuildings were furnished. Almost at the same time as

the renovation of Hohenschwangau, from 1836 to 1842, Marie's cousin, the Crown Prince and, since 1840, Prussian

King Friedrich Wilhem IV, rebuilt Stolzenfels Castle on the Rhine again in a similar style.

In 1848 Max ascended the throne as Maximilian II. At that time, new wings were built for the court, including the

cavalier's building in 1855. The palace served the royal family as a summer residence and was the nursery two of

the king's sons, the later kings Ludwig II and Otto. Ludwig II frequently used the palace, including during the

construction of Neuschwanstein Castle from 1869 to 1884, which was officially named Neue Burg Hohenschwangau

until 1886. Ludwig II did not change anything in Hohenschwangau except his own bedroom, in which he had a

display of rocks built in 1864, over which a waterfall flowed, as well as an apparatus for generating an artificial

rainbow and a night sky with moon and stars, which is visible from the upper floor through a complicated system

of mirrors were illuminated from. After Ludwig's death in 1886, Queen Marie had the room restored to its original

condition. She died almost three years after the death of her son in 1889 at Hohenschwangau Castle.

From 1923 until the present, the castle has belonged to the Wittelsbach Compensation Fund and is used as a museum.

It is still occasionally used by members of the Wittelsbach family on special occasions. Prince Adalbert of Bavaria

retired to Hohenschwangau Castle in 1941 after he had left the Wehrmacht.

Hohenschwangau Castle was built into the partially preserved outer walls of Schwanstein Castle from the 14th

century between 1537 and 1547. The four-storey complex of the main building, which was redesigned in a

neo-Gothic style both inside and out from 1833–1837, with a yellow facade, has three round towers with polygonal

superstructures, the gate building is three-stories high. The main building houses a museum. The interior furnishings

from the Biedermeier period, have been preserved unchanged. The rooms are still furnished with the furnishings

from the restoration period. (Marcus Spangenberg / Bernhard Lübbers (eds.): Dream castles? The buildings of

Ludwig II as tourism and advertising objects. Dr. Peter Morsbach, Regensburg 2015)

(Zairon Photo)

Schloss Hohenschwangau.

(Softeis Photo)

Ettal: Schloss Linderhof is a palace, in southwest Bavaria near the village of Ettal. It is the smallest

of the three palaces built by King Ludwig II of Bavaria and the only one which he lived to see completed.

Ludwig already knew the area around Linderhof from his youth when he had accompanied his father King

Maximilian II of Bavaria on his hunting trips in the Bavarian Alps. When Ludwig II became King in 1864, he

inherited the so-called Königshäuschen from his father, and in 1869 began enlarging the building. In 1874, he