The 1759 Campaign in Québec

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theatre of the Seven Years’ War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various First Nations warriors. When the war be3gan, the French colonies had a population of roughly 60,000 settlers, compared with 2 million in the British colonies. The outnumbered French particularly depended on their First Nations allies. French Canadians call it the guerre de la Conquête (War of the Conquest). The British colonists were supported at various times by the Iroquois, Catawba, and Cherokee tribes, and the French colonists were supported by Wabanaki Confederacy member tribes Abenaki and Mi’kmaq, and the Algonquin, Lenape, Ojibwa, Ottawa, Shawnee, and Wyandot (Huron) tribes. Fighting took place primarily along the frontiers between New France and the British colonies, from the Province of Virginia in the south to Newfoundland in the north.

In 1755, six colonial governors met with General Edward Braddock, the newly arrived British Army commander, and planned a four-way attack on the French. None succeeded, and the main effort by Braddock proved a disaster; he lost the Battle of the Monongahela on July 9, 1755, and died a few days later. British operations failed in the frontier areas of the Province of Pennsylvania and the Province of New York during 1755–57 due to a combination of poor management, internal divisions, effective Canadian scouts, French regular forces, and Native warrior allies.

(Saltwire Photo)

Aerial view of the Fort Beausejour-Fort Cumberland site in Aulac, New Brunswick.

In 1755, the British captured Fort Beauséjour on the border separating Nova Scotia from Acadia.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 2835041)

Embarkation of the Acadians, 1755, C.W. Jeffreys artwork.

Following the capture of Fort Beauséjour, the British ordered the expulsion of the Acadians (1755–64) soon afterwards. Orders for the deportation were given by Commander-in-Chief William Shirley without direction from Great Britain. The Acadians were expelled, both those captured in arms and those who had sworn the loyalty oath to the King. First Nations residents were also driven off the land to make way for settlers from New England. (Eccles, France in America)

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 2836823)

Montcalm focused his meager resources on the defence of the St. Lawrence, with primary defenses at Carillon, Quebec City, and Louisbourg, while Vaudreuil argued unsuccessfully for a continuation of the raiding tactics that had worked quite effectively in previous years. Between 1758 and 1760, the British military launched a campaign to capture French Canada. They succeeded in capturing territory in surrounding colonies and ultimately Quebec City in 1759.

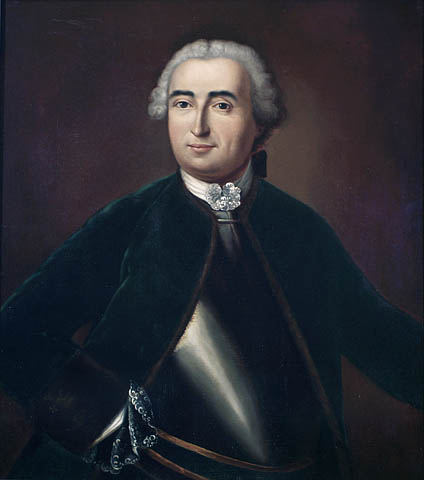

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 2895029)

Louis-Joseph, Marquis de Montcalm.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 2936201)

View of Quebec in 1755.

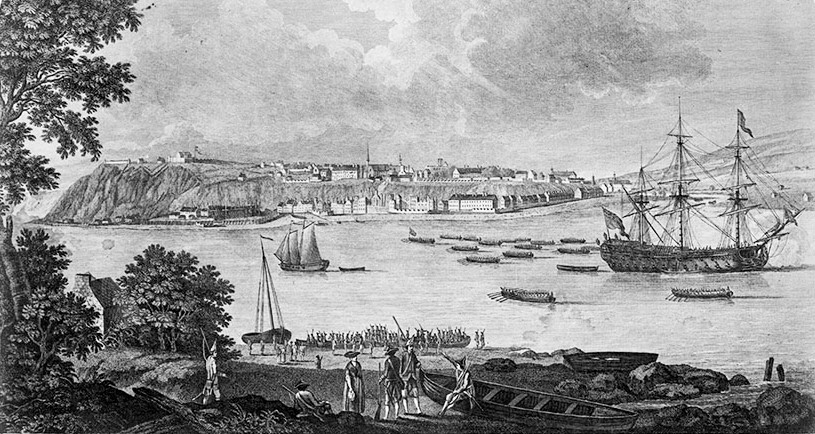

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 2935947)

Quebec, the capital of New France, 1 January 1759, engraving by Thomas Johnston.

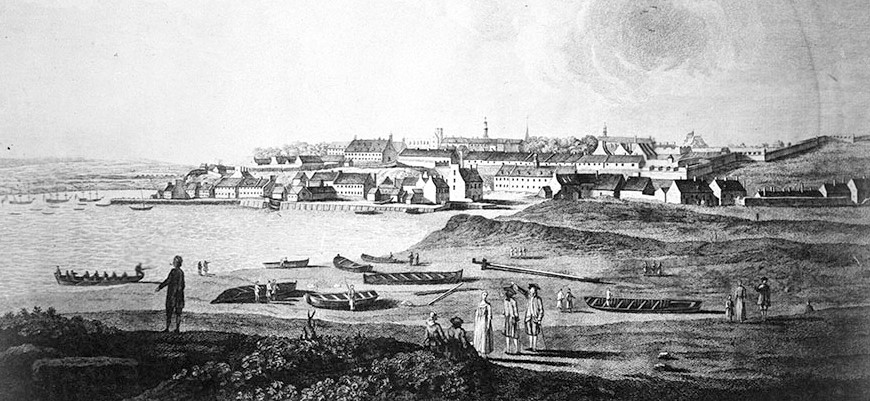

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3574556)

View of Quebec from Point-Levis, 1759.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3574558)

View of Quebec from St. Charles River, 1759.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 2890412)

French Fireships attacking the British Fleet at Anchor before Quebec, 28 June 1759.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3574571)

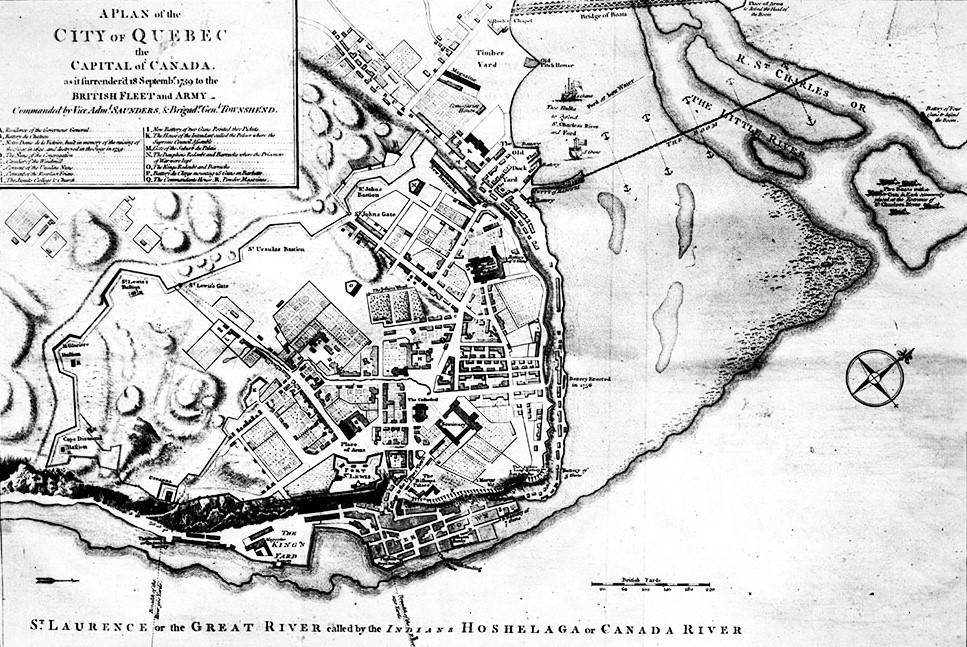

Plan view of Quebec at the time of the 1759 siege.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3574570)

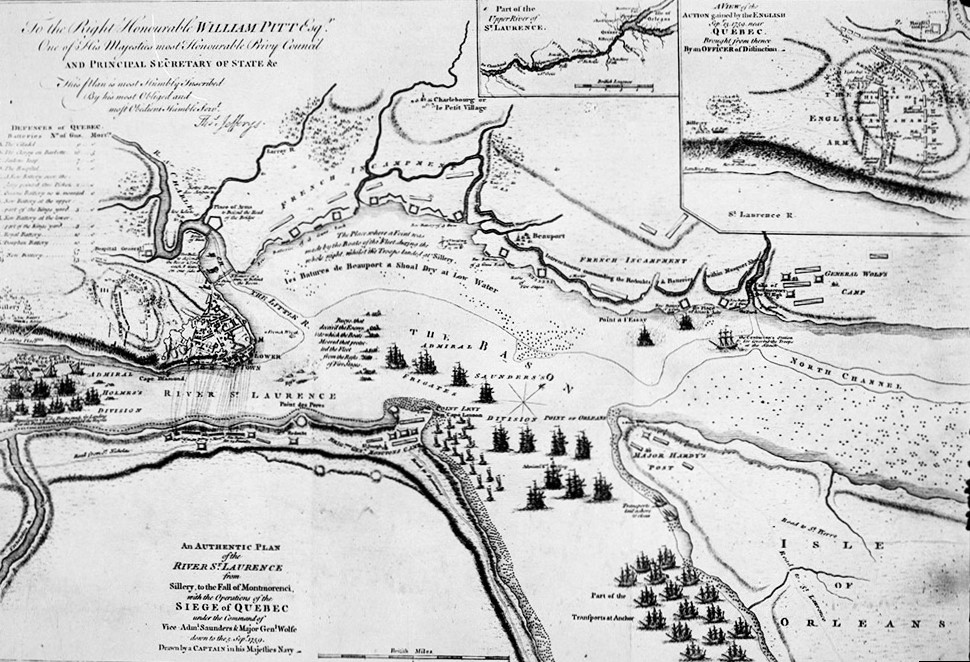

Plan of the St. Lawrence, operations of the siege and the environs of Quebec and the Battle fought on the Plains of Abraham on 13 July 1759. Details include the details of The French Lines and Batteries, and also of the Encampments, Batteries and attacks of the British Army, and the Investiture of that City under the Command of Vice Admiral Saunders, Brigadier General Wolfe, Brigadier General Moncton and Brigadier General Townshend. Drawn from the original surveys taken by the Engineers of the Army. Engraved by Thomas Jefferys, Geographer to His Majesty.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN 2877337)

Vice Admiral Charles Saunders.

“The British army under Wolfe was transported by a fleet of over 200 sail, commanded by Vice Admiral Charles Saunders.[1] Entering the St. Lawrence on the 6th of June, Admiral Saunders appointed Captain James Cook (of later Pacific fame) to sail ahead, take soundings, and buoy a channel through the Traverse, the narrow, tortuous channel between Ile d’Orleans and the south shore.[2] He then performed the amazing feat of sailing his entire fleet up to Québec in three weeks, without a single grounding or other casualty.[3]

Major-General Jeffery Amherst, later governor of British North America.

General Amherst, marching overland from New York, was supposed to cooperate. He recaptured Crown Point and Ticonderoga but was slow and methodical to get within striking distance of Québec.[4] Three times in previous wars this failure in coordination had saved Québec for France, and in 1775-76 and 1812-13 similar American failures kept it British. Wolfe, however, took his total force of 4,000 (not including sailors and marines) “including some of the crack units of the British army.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3362014)

Re-enactors in the uniforms of Montcalm’s soldiers in 1908.

Owing to Amherst’s delay, the Marquis de Montcalm was able to concentrate some 14,000 French troops and militia in around Québec. His position appeared to be impregnable. The guns of the citadel commanded the river, and two smaller rivers barred the land approach from the east.[5]

On the 27th of June Admiral Saunders landed an armed force on the on the Ile d’Orleans, four miles below Québec. General Montcalm had deployed his army along the north shore of the river, between the St. Charles and the Montmorency. He also had a detachment under Colonel Bougainville to the west of the city; but he neglected to secure the south bank. General Wolfe took immediate advantage of this weakness and seized Point Lévis, approximately 1000 yards across the river from Québec. From this position, he was able to place his guns in range to bombard the lower town. On the 9th of July, Wolfe reinforced his position by landing the better part of two brigades on the north shore, just below Montmorency falls. This was also intended to act as a decoy to fox Montcalm. Ten days later, one of the frigates and several smaller vessels, slipped past the guns of Québec under cover of a heavy bombardment from Point Lévis. The miniature fleet proceeded to sail over twenty miles upstream with the object of confusing Montcalm and also to provide Wolfe with possible alternative points of attack. Because of their command of the river, the British were now able to select an optimal time and place for their main assault.[6]

Wolfe initially probed along the Montmorency front, but he failed to make any gains there. He then quietly reinforced the up-river part of his force with additional men and ships, sailing them up and downstream with the wind and tide. This in turn forced Colonel Bougainville to march and countermarch his soldiers until they were exhausted. While this was going on, Wolfe’s scouts discovered a narrow defile that led up the steep cliffs of the St. Lawrence River’s north bank to the Plains of Abraham. Montcalm had thought that route was inaccessible and had therefore posted only a small picket guard to cover this approach.[7] His mis-appreciation of the situation would prove to be costly.

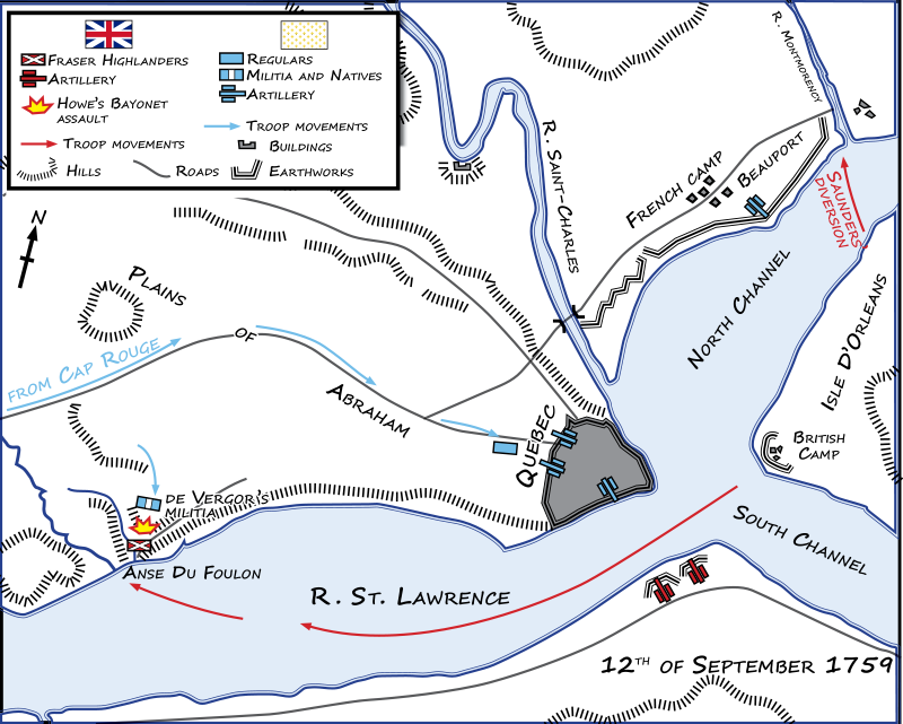

Admiral Saunders carried out a simulated landing on the Montmorency front at sunset on the 12th of September. This maneuver pulled a large part of Montcalm’s force out of their position. Late that evening 1,700 English soldiers embarked in boats from the transports up-river, and at 2 o’clock on the morning of the 13th of July, they began floating downstream. They were aided in the venture by a fresh breeze astern and an ebb tide under their keels and succeeded in carrying out the operation unobserved by Colonel Bougainville’s sentries.[8]

[1] Sir Charles Saunders (1715-1775) entered the Royal Navy in 1727 under the patronage of a relative and in 1739 was appointed first lieutenant of the Centurion, the flagship of Commodore George Anson in his circumnavigation of the world from 1740 to 1744. Saunders sailed a sloop around Cape Horn, captured Spanish shipping in the Pacific, and returned to England a post-captain. During the remainder of the War of the Austrian Succession he commanded several ships of the line with success; in 1746, in the Gloucester, he took part in the capture of a treasure ship bound for Spain and acquired about 40,000 pounds of the booty. The following year, in the Yarmouth, he took two enemy warships when Admiral Sir Edward Hawke defeated Admiral L’ Ètenduère off Cape Ortegal, Spain, on the 19th of October. Saunders was promoted to the rank of rear-admiral of the blue on the outbreak of the Seven Years’ War in January 1756. On the 9th of January 1759, recommended by Anson, he was appointed commander of the fleet bound for the St. Lawrence. One month later he was promoted vice-admiral of the blue. Major-General James Wolfe joined Saunders aboard his flagship Neptune on the 13th of February. Both men had been warned by Pitt that success depended “on an entire Good Understanding between our Land and Sea Officers.” Saunders was ordered to “cover the army against French naval intervention and keep control of the line of communication. He was left however, to decide to what extent his fleet would directly aid Wolfe’s forces. This he did with a great deal of success. Saunder’s achievement at Québec had been to organize and conduct a large expedition up a difficult river and maintain it there. The success reflected not only his professionalism, but also the advances that had been made in the navy in recent years, such as the development of reliable navigational devices, the improvements in marine surveying and charting, and the development of landing craft for amphibious operations. His contribution did not end with the capture of the fortress of Québec, for had he not supplied the garrison with cannon, ammunition, and provisions before he left, even to the extent of reducing ships’ stores, Québec might well have been recaptured by the French under Lévis the following spring.” The Encyclopedia Americana, International Edition. Connecticut, Grolier Inc, Danbury, 1988, pp. 698-701.

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham, PC, FRS, (15 November 1708 – 11 May 1778). Pitt was a member of the British cabinet and its informal leader from 1756 to 1761 (with a brief interlude in 1757), during the Seven Years War. It is said that Pitt’s power was based not on his family connections but on the extraordinary parliamentary skills by which he dominated the House of Commons. He displayed a commanding manner, brilliant rhetoric, and sharp debating skills that cleverly utilised broad literary and historical knowledge.

[2] In 1758 James Cook served at the siege of Louisbourg during the Seven Years War. He charted part of Gaspé and helped to prepare the map that enabled James Wolfe’s armada to navigate the St Lawrence. The campaign against Québec in 1759 led to the making of a chart of the St Lawrence by James Cook and other naval surveyors. He extensively mapped Newfoundland’s coast including St Johns’ harbour. He later circumnavigated the South Pacific in 1768-71 and 1772-75. In July 1776 he began a third voyage to search for a Northwest Passage. Anchored in Nootka Sound on Vancouver Island 29 Mar 1778. Sailed to Bering Strait but ran into a wall of ice. Cook was killed (and eaten) in the Sandwich Islands in an altercation with the local people. George Vancouver sailed with him on his second and third voyages.

[3] Samuel Eliot Morison, The Oxford History of the American People, New York, 1965, p. 167.

[4] At the Battle of Dettingen on the 12th of June 1743, four young English officers, Jeffrey Amherst, George Townshend, Robert Moncton, and James Wolfe had received their baptism of fire (Wolfe had his horse shot out from under him). Samuel Eliot Morison, The Oxford History of the American People, New York, 1965, p. 165. Dettingen was a battle fought between the French and the English during the War of the Austrian Succession. Oliver Warner, With Wolfe to Quebec, p. 18.

[5] Ibid, p. 167.

[6] Ibid, p. 167.

[7] Ibid, p. 167.

[8] Ibid, p. 167.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 2894990)

Portrait of General James Wolfe by Joseph Highmore (1692-1780).

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 165505)

A correct plan of the environs of Quebec, and of the battle fought on the 13th September, 1759: together with a particular detail of the French lines and batteries, and also of the encampments, batteries and attacks of the British army, and the investiture of that city under the command of Vice Admiral Saunders, Major General Wolfe, Brigadier General Monckton, and Brigadier General Townshend. Drawn from the original surveys taken by the engineers of the army. Engraved by Thomas Jefferys, geographer to His Majesty.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 2873842)

Brigadier General Monckton, later Major General, the Honorable Robert Monckton, (1726-1782).

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 2895905)

Wolfe’s assault boats heading to shore above Quebec, 13 Sep 1759, painted in 1763.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No.3007596)

A view of the taking of Quebec, 13 September 1759. Engraving based on a sketch made by Hervey Smyth (1734-1811), General Wolfe’s aide-de-camp during the siege of Quebec. General Wolfe was positioned in one of the leading boats, and as the men rowed to their destination with destiny, it is reported that he was overheard reciting the words from Gray’s “Elegy in a Country Churchyard” to a young midshipman. In an eerie prediction of what would be his fate on the following morning, he solemnly pronounced the famous line “The paths of glory lead but to the grave.”[1]

Map showing the route of Wolfe’s assault boats as they reached the bottom of the defile alongside the steep cliffs of Quebec’s north shoreline.

The French sentries had been expecting a convoy of boats carrying badly needed provisions to slip down-river that night, and the British landing craft were therefore mistaken for them. Only one French sentry on the shore challenged them with the traditional: “Qui vive?” A French-speaking Scot replied: “Française!” “De quel régiment?” “De la Reine,” replied the Scot. The events that followed did not unfold in the disaster for the English that had occurred when the same challenge that had been issued to Howe’s men at Lake George. It would appear that the Scot must have gotten the accent right, because “the sentry was satisfied.”[2]

Wolfe’s boats reached the bottom of the defile alongside the steep cliffs of Quebec’s north shoreline. Quickly and efficiently, 25 rugged volunteers climbed up the cliff and immediately put the French picket guard to the sword. They then gave a prearranged signal, and the troops waiting in the boats below jumped ashore and swarmed up the steep path with their muskets slung over their backs. As soon as the assault landing boats were emptied, they quickly returned to the support ships or to the south shore for additional reinforcements. The end result of this effective execution of a difficult tactical operation was that, by break of day, on the 13th of September 1759, some 4,500 British were deployed a grassy field forming part of the Québec plateau, close to the walls of the citadel. This field would soon give its name to one of the most important military actions in North American history, the Battle on the Plains of Abraham.[3]

[1] Ibid, p. 168.

[2] Ibid, p. 168.

[3] Ibid, p. 168.

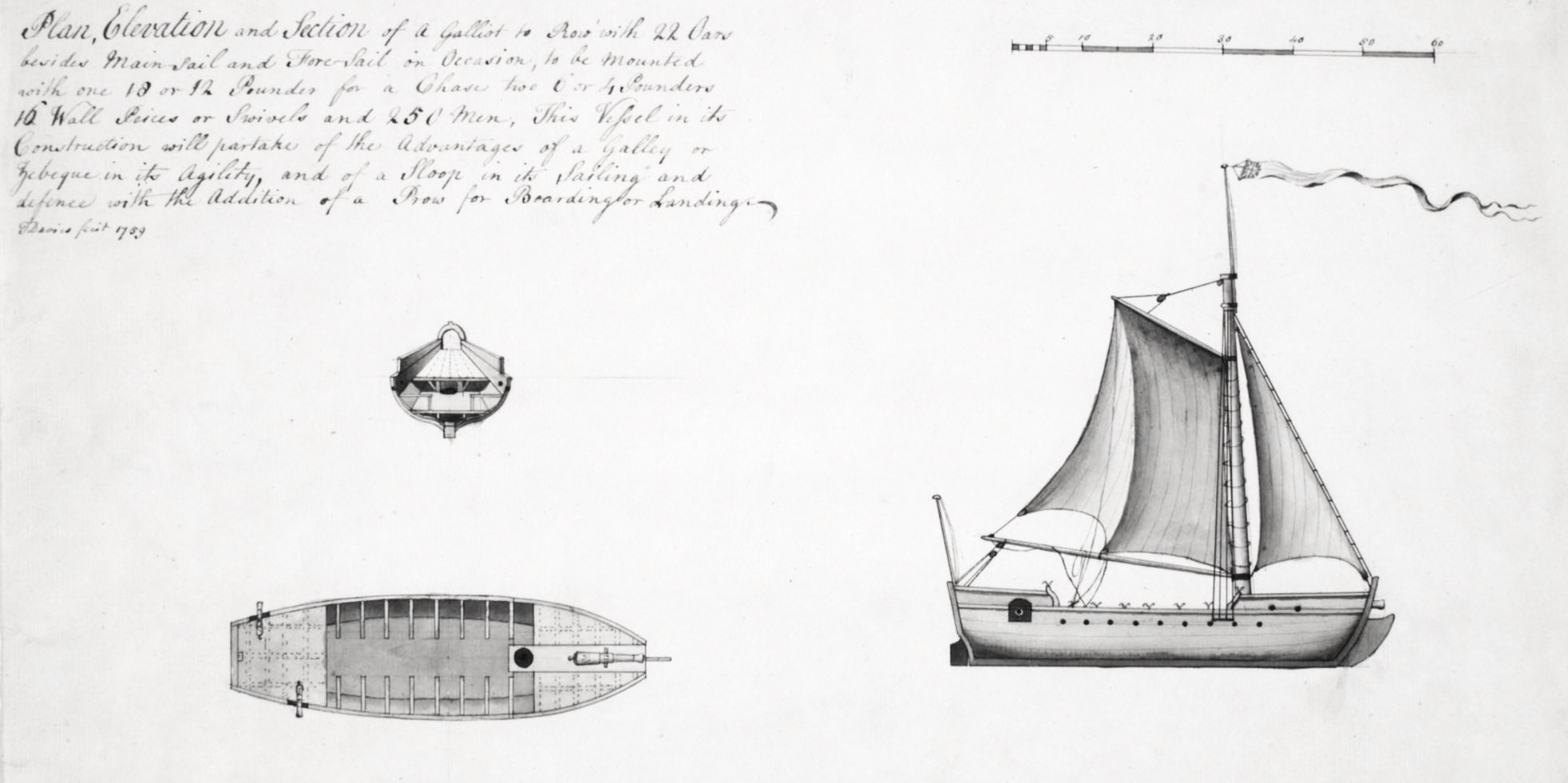

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 2834121)

Plan, Elevation and Section of a Galliot used to take Wolfe’s troops ashore, 1759.

The Plains of Abraham

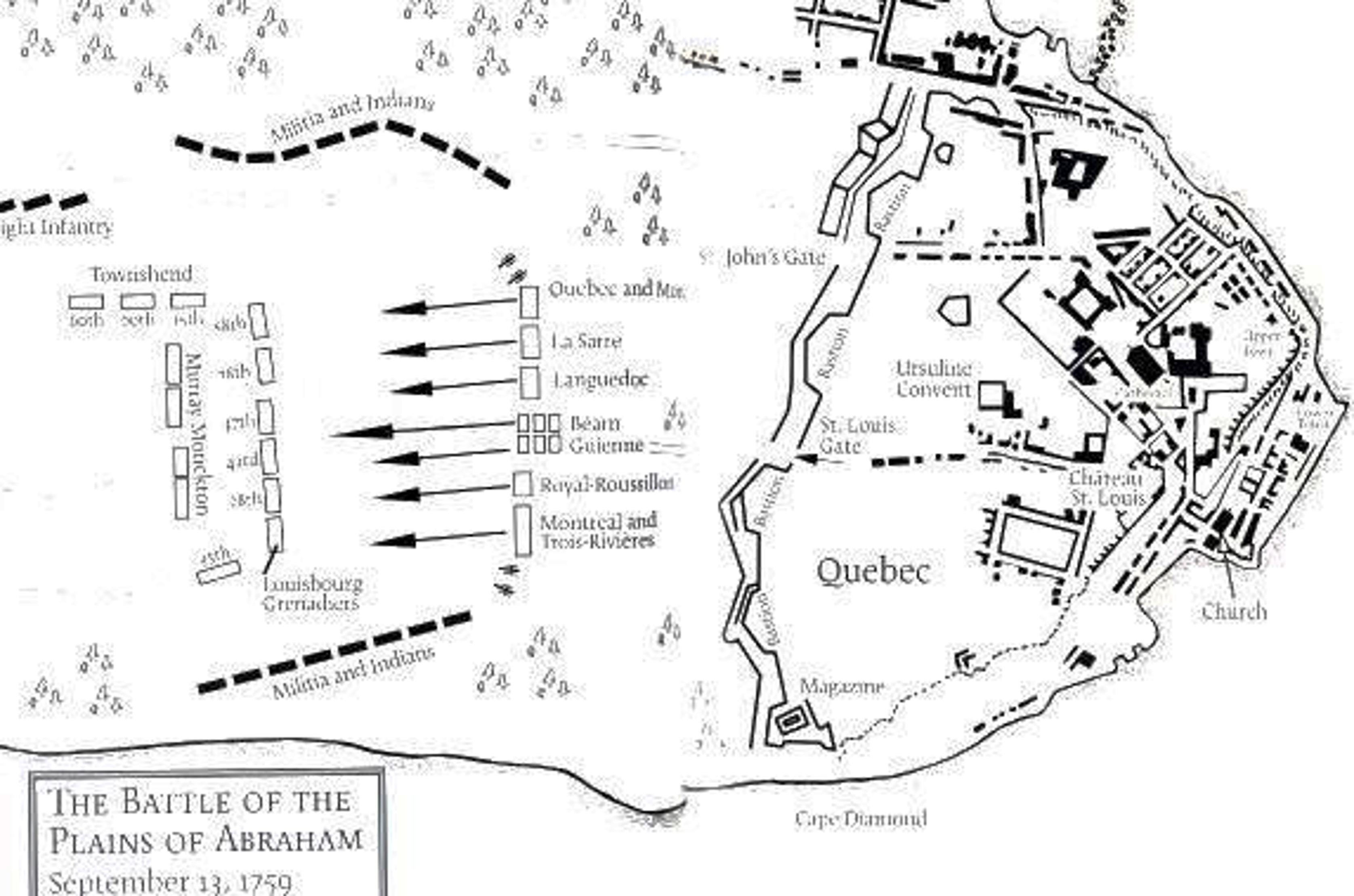

(Map courtesy of Hoodinski)

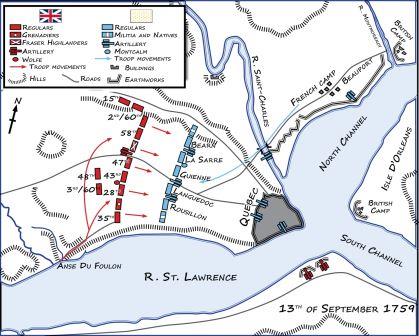

Map of the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, 1759.

With his forces formed up in battle formation on the Plains of Abraham facing the city, Wolfe’s primary objective was to challenge Montcalm to an open-field battle. This was the only kind he knew how to fight; and the French accepted.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 2933739)

Engraving of General Wolfe and his troops on the heights of Abraham, Quebec, 13 September 1759.

Accompanied by his aides-de-camp (ADCs), “who were his means of conveying orders, Wolfe had first made a reconnaissance towards the city to decide the best ground to take up. By 8 o’clock, with the light excellent, additional British soldiers commanded by Colonel Ralph Burton had been brought “over from Point Lévis, and the army was concentrated.”[1]

Wolfe knew that he had to have open ground for the effective deployment of his forces. The ground that comprised the Plains of Abraham lay in front of him and was between him and Québec. The ground appeared to be ideal for the kind of combat that his European trained regular soldiers needed. It afforded them a certain amount of cover and concealment (and therefore protection), with its contours, although there were “danger zones” on either flank. Woods and shrubs on each side gave Canadians and Indians good cover to infiltrate and ambush his troops. The protective cover the woods offered and the ground in front of them were exactly the sort of terrain to which the woodsmen of New France were best suited, and from the earliest hour they seized every chance to harass their British enemies. Long before Montcalm carried out his main advance, skirmishing was continuous, though it was never becoming serious enough to hold up Wolfe’s detachment.[2]

By 6 o’clock, three of Wolfe’s battalions and the Louisbourg Grenadiers were in line and arranged so that they faced the walls of the city of Québec. The lines continued to be adjusted, revised, and extended as more units came up. In the end, the British force arrayed on the field consisted, from right to left, of the 35th battalion, which was on the flank facing the cliff, the Louisbourg Grenadiers, the 28th, 43rd, 47th, 78th (Highlanders), 58th, and then, on the left flank, the 15th and the Royal Americans.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 2833382)

78th Regiment of Foot Guards: Fraser’s Highlanders 1759

(Library and Archives Canada, MIKAN No. 2837335)

French Canadian Militia, 1759.

Wolfe’s Light Infantry were already dealing with the Canadian militia and Indians in the wooded area still further to the left, and he had deployed a detachment of Royal Americans to guard the route back to the Foulon. The 48th battalion under Colonel Ralph Burton formed a reserve and occupied a place behind General Robert Monckton, who had command of the right. Brigadier General James Murray was in charge of the centre and General George Townshend had command of the left flank.[3]

Wolfe positioned himself at the head of the Louisbourg Grenadiers on the right flank. When his forces were finally deployed in their pre-arranged order of battle, they were slightly nearer to the walls of Québec that any other part of the line. He was needed to be close at hand to direct Colonel Ralph Burton’s reserve forces should the need arise.[4]

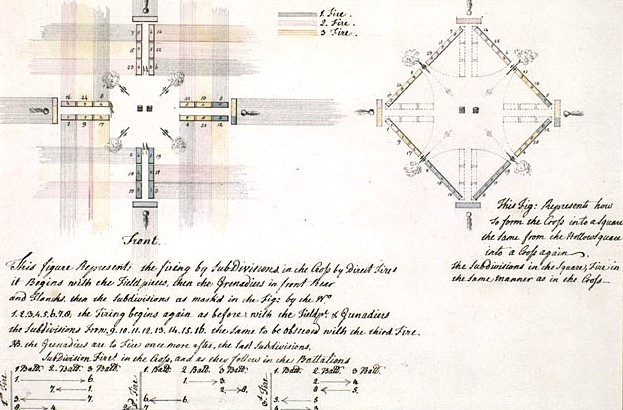

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 2834123)

Cross and Square Formations, 1759.

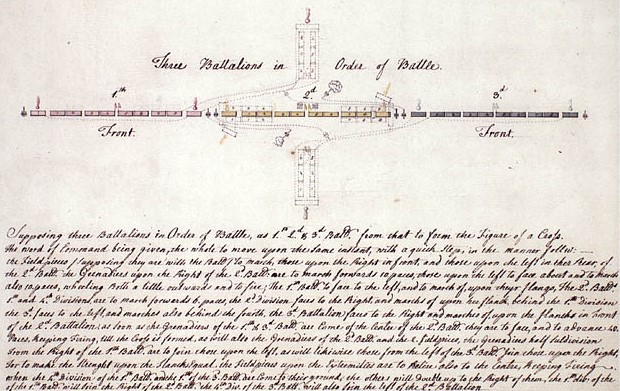

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 2834122)

Three battalions in Order of Battle, 1759.

The English forces consisted of the six battalions previously named and the detached Grenadiers from Louisbourg, which were all drawn up in ranks three deep. Wolfe’s right wing was near the brink of the heights along the St Lawrence; but the left could not reach those along the St Charles. On this side a wide space was left open, and there was a danger of being outflanked there. To prevent this, Brigadier George Townshend was stationed there with two battalions, drawn up at right angles with the rest, and fronting St Charles. The battalion of Major General Daniel Webb’s regiment, under Colonel Ralph Burton, formed the reserve; the third battalion of Royal Americans (mentioned by Elijah), was left to guard the landing site; and Howe’s light infantry occupied a wood far in the rear. James Wolfe, with Robert Monckton and James Murray, commanded the front line, on which the heavy fighting was to fall, and which, when all the troops had arrived, numbered less than 3,500 men.

Brigadier George Townshend later estimated that Wolfe had about 4,400 men at his disposal and reckoned that Montcalm would have opposed on the battlefield with about the same number of troops.[5]

Although the Canadians and Indians were firing at his forces from the flanks, Wolfe was able to issue his battle-orders relatively undisturbed by the French opposition. Montcalm, however, was in a hugely different situation. Whenever he was at Beaufort, he would customarily spend his time booted and spurred, regardless of the time of day or night, in order to be prepared to meet any challenge.[6] As he came riding up from the Beauport shore on a black charger he looked towards Vaudreuil’s house. This was Montcalm’s first view of the red ranks of the British soldiers forming on the heights across the St Charles some two miles away. “This is serious business,” he said, and sent off Chevalier Johnstone at the full gallop to bring up the troops from the centre and left of the camp. The troops on his right were already in motion, no doubt because of an order to do so by the Governor.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 2896948)

Montcalm on the Plains of Abraham., painting by A.H. Hider.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 2895086)

Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil de Cavagnial, Marquis de Vaudreuil (1698-1778).

Vaudreuil came out and spoke briefly with Montcalm, who then put the spurs to his horse, and rode over the St Charles bridge to bring himself to the scene of danger. It is reported that he rode with a fixed look, not saying a word. Major Malartic, of the Béarn battalion of French regulars, rode beside his chief as he made his way towards his opponent. As a rule, Montcalm was an animated talker, now he was silent. To Major Malartic, it seemed “as though he felt his fate upon him.”[7]

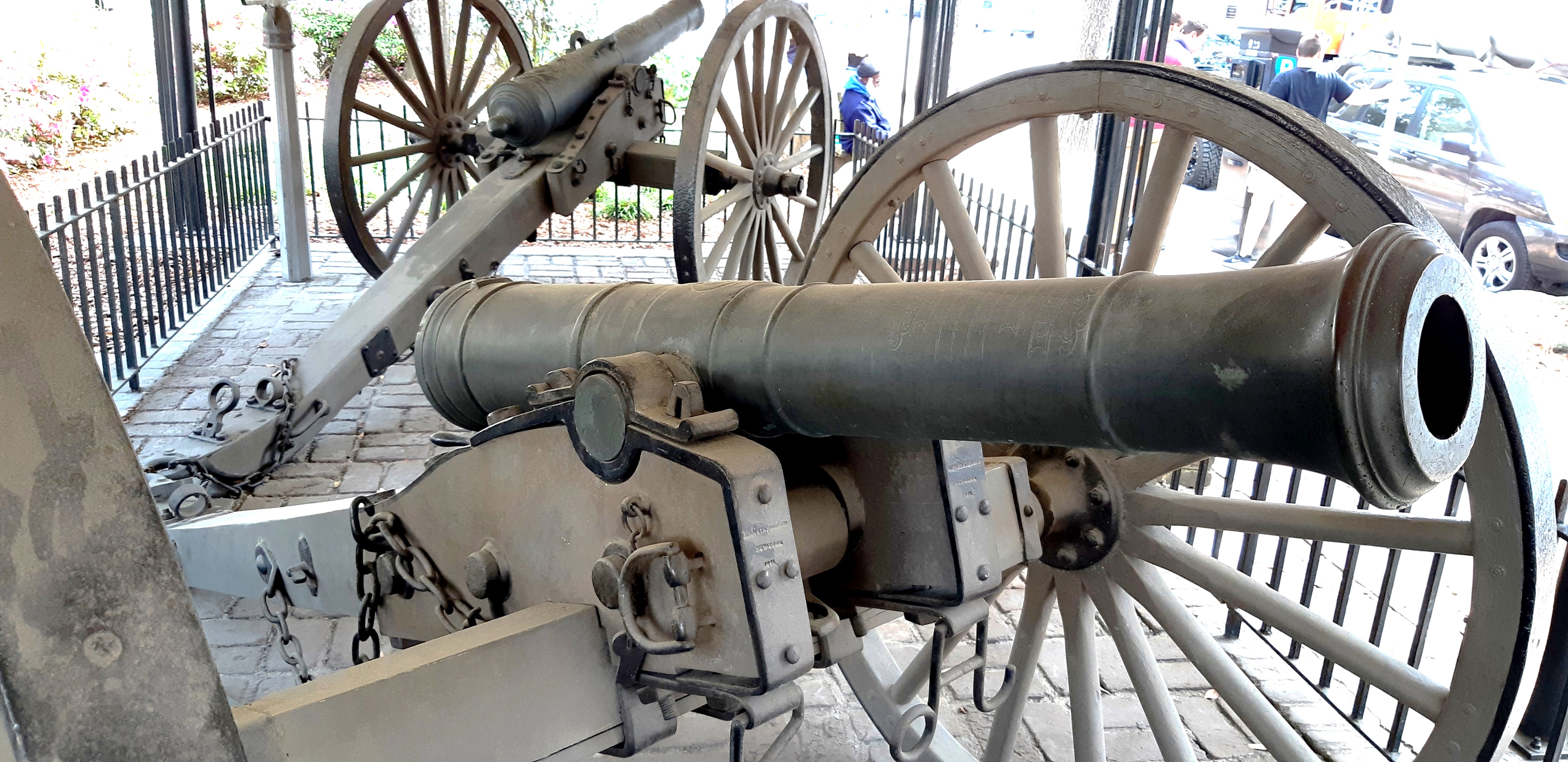

(Author Photo)

French bronze 6-pounder SBML Gun mounted on a field carriage, Savannah, Georgia.

Montcalm was incredulous. He had expected a detachment, and instead he found an army. In the face of this force, Vaudreuil held back the forces that Montcalm had ordered to join him. The Québec garrison also refused to come to his aid. He sent to Ramesay, its commander, for 25 fieldpieces, which were on the palace battery. Ramesay would only give him three, saying that he wanted them for his defence.[8]

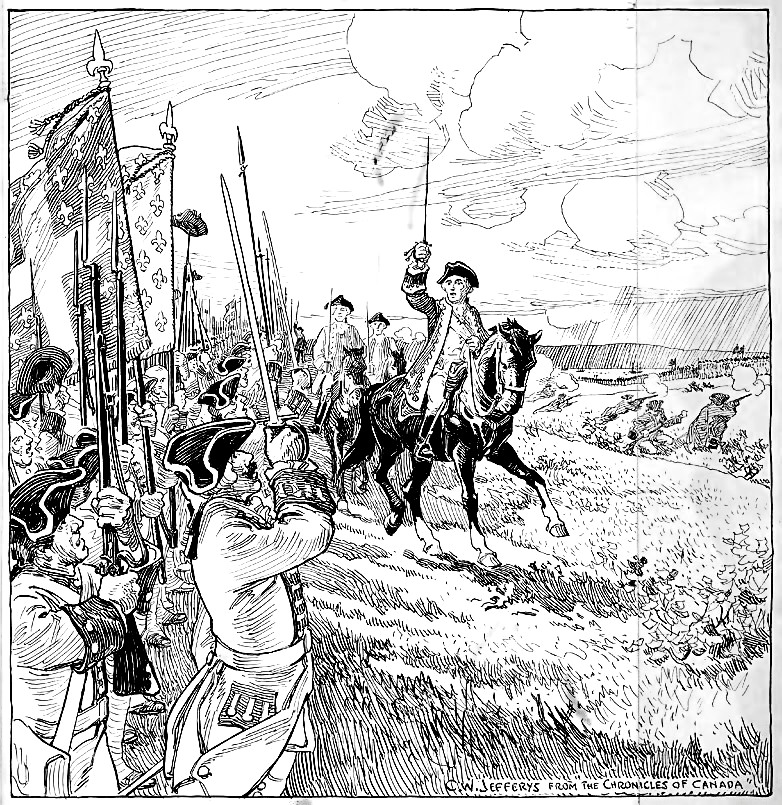

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 2897202)

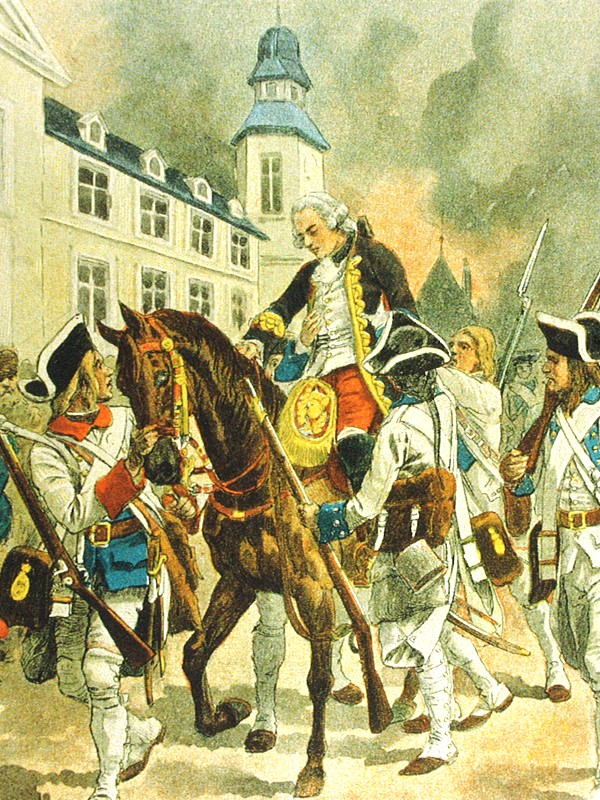

Montcalm leading his troops at the Plains of Abraham by Charles William Jeffreys (1869 – 1951).

Montcalm held a council of war with his chief officers, and they agreed on an immediate attack, believing that there was no time to lose, for he thought that Wolfe would be reinforced. Montcalm has been blamed not only for fighting too soon, but also for fighting at all. In this he could not choose. He had to fight, because Wolfe was now in a position to cut off all of his supplies. His men were primed for battle, and he resolved to attack before they lost their eagerness. He spoke a few words to them in his keen, vehement way, riding a black or dark bay horse along the front of the lines, brandishing his sword. He wore a coat with wide sleeves, which fell back as he raised his arm, and showed the white linen of the wristband.[9]

[1] Oliver Warner, With Wolfe to Québec, p.159.

[2] Ibid, p.159.

[3] Ibid, pp.159-160.

[4] Ibid, p.160.

[5] Ibid, p.161.

[6] Ibid, p. 161.

[7] Ibid, p. 164

[8] Francis Parkman, Montcalm and Wolfe, p. 476.

[9] Ibid, pp. 476-477.

The French army followed in such order as it might, crossed the bridge in haste, passed under the northern rampart of Québec, entered at the Palace Gate, and pressed on in a headlong march along the narrow streets of the old town. Troops of Indians joined them in scalplocks and warpaint, along with bands of Canadians for whom much was at stake in this battle, in addition to the colony regulars; the battalions of Old France, white uniforms and bayonets of the veterans of famous regiments of La Sarre, Languedoc, Royal Roussillon, Béarn, who had fought at Oswego, Fort William Henry and Ticonderoga. They poured out through the gates of St Louis and St John and raced to where the banners of Guyenne still fluttered on the ridge, racing at the double from the Montmorency front, rushing through the narrow streets of Québec and deploying on the other side to face the English.[1]

Montcalm had deployed his forces in the following order: on his right was the regular contingent from Québec and Montréal, flanked in the woods by Canadian militia and Indians under Dumas. In the centre came the five attenuated French battalions, La Sarre, Languedoc, Béarn, Guyenne and Royal Roussillon. On his left flank he had deployed the men of Trois Rivières and Montréal; with the militia and Indians being spread out, just slightly ahead of them near the edge of the cliff. Montcalm had only five guns to bring to bear on the British forces facing him. He might have been able to put more on the line had he and his forces been given time to organize. This was one of the most important advantages Wolfe had achieved when he gained the element of surprise by seizing the heights. Even so, the five French guns were three more than Wolfe’s men had thus far been able to haul up the cliff.[2]

As he was crossing the battlefield on one of his errands, Montbelliard stopped to speak with Montcalm just before the general gave the word to advance. Montcalm informed him that, “We cannot avoid action. The enemy is entrenching. He already has two pieces of cannon. If we give him time to establish himself, we shall never be able to attack him successfully with the sort of troops we have.”[3]

[1] Ibid, p. 477.

[2] Oliver Warner, With Wolfe to Québec, p. 165.

[3] Ibid, p. 165.

(C.W. Jefferys, Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 2835227)

Montcalm Riding Along the French Lines Before the Battle of the Plains.

At about 10 o’clock, Montcalm gave the command, and the French advanced. The British were not entrenched, as Montcalm supposed. They were lying down, except for those actively engaged on the flanks, having been employed in making sure that their first volley, double-shotted, was ready. That seen to, no doubt they consumed some of the two days’ rations, and the rum, which they had taken with them into the boats. Wolfe placed his battalions in open order, with forty-yard intervals between them, and as the line was extended, and many troops were needed to guard the flanks, the ranks were only two deep.[1]

Roughly 4,000 French soldiers had by now formed up outside the walls. They began their advance to the attack, flying regimental colours and cheering “Vive le Roi!” According to Major Malartic, who as a regimental officer would have noted such an important detail, “The French came on too fast, at a run.” The result was that the formations began to go to pieces almost at once, taking on a ragged appearance. “We had not gone twenty paces,” said Malartic, “before the left was too far in the rear, and the centre was too far in front.” Worse even than that, the first French volley was fired too far from the British to be fully effective, and the second was feeble or non-existent, for the Canadian-born troops who reinforced the French battalions, “according to their custom, threw themselves on the ground to reload.” When they rose, it was not to fire again, but to retreat. They had no stomach for the sort of fighting, volleys followed up by an assault with the bayonet, for which the regulars had been drilled. “The scarlet-coated British and the white-coated French were now in direct contact, but as yet, no firing had come from Wolfe’s ranks.”[2]

For fifteen or twenty minutes they marched, and not a shot rang out; Wolfe had learned the value of precise, accurate, and concentrated firepower. Three-quarters of his 4,500 troops were deployed in one line, which waited silently until the enemy was only 40 yards away. Their Brown Bess muskets had already been loaded, following a complex sequence of orders: “Handle Cartridge,” (draw the cartridge from the pouch and bit the top off), “Prime,” (shake the powder into the priming pan), “Load,” (put the ball and wadding into the barrel), “Draw ramrods” (press down with ramrod and withdraw), “Return ramrods,” (return to loop on the musket and fix bayonet), “Make ready,” (face to front), “Present,” (take aim and prepare to fire). Only the order “Give Fire” was reserved until the last second.[3]

The English waited and watched. The three field pieces sent by Ramesay fired on the English with canister-shot, and 1,500 Canadians and Indians fusilladed them in front and on the flanks. Skirmishers were sent out to hold them in check, and the soldiers were ordered to lie on the grass to avoid the shot. Casualties were heavy among Brigadier George Townshend’s men. Towards 10 o’clock the French formed themselves into three bodies on the ridge, with their regulars in the centre, and other regulars and Canadians on the left and right.

(Author Photo)

British bronze 6-pounder SBML gun, Savannah, Georgia.

Two fieldpieces, which had been dragged up the heights at Anse du Foulon, fired on them with grapeshot, and the troops, rising from the ground, prepared to receive them.

In a few moments they were in motion. They came on rapidly, uttering loud shouts, and firing as soon as they were within range. Their ranks, ill ordered at the best, were further confused by a number of Canadians who had been mixed among the regulars, and who, after hastily firing, threw themselves on the ground to reload.

The British advanced a few rods, then halted and stood still. When the French were within forty paces the word of command rang out and a crash of musketry answered all along the English line. The volley was delivered with remarkable precision. To the battalions of the centre, the simultaneous explosion sounded like a single cannon shot. Another volley followed, and then a furious clattering of fire that lasted just a minute or two. When the smoke cleared, the ground was littered with French dead and wounded, the advancing masses stopped short and turned into a frantic mob, shouting and cursing.[4]

Sir John Fortescue, historian of the British Army, spoke of this volley as:

the most perfect ever fired on a battlefield, and it was decisive. It was not quite instantaneous, except in the centre, where it seems to have been delivered like a single cannon shot, but it was near enough. The climax came within seconds, not minutes, and as a regular formation, Montcalm’s army broke and fled. In those seconds, Wolfe had the fullest justification for years of rigorous discipline and training.

The volley was among the last sounds he heard coherently.[5]

[1] Ibid, pp. 165-166.

[2] Ibid, pp. 166.

[3] Ibid, pp. 166.

[4] Francis Parkman, Montcalm and Wolfe, p. 478.

[5] Oliver Warner, With Wolfe to Québec, p. 167.

The Loss of Wolfe and Montcalm

The order was given to charge and over the field rose a British cheer mixed with the fierce yell of the Highlanders. Some of the corps pushed forward with the bayonet, others advanced firing. The clansmen drew their broadswords and crashed on. [1]

[1] Francis Parkman, Montcalm and Wolfe, p. 478.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 2835895)

Wolfe at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. C.W. Jefferys.

Off to the right flank of the English forces, a steady small arms fire continued to be maintained, even though the attacking column had been broken. This fire was being sustained by a number of mainly from sharpshooters who were laying in the brush and cornfields. This is where Wolfe chose to lead a charge at the head of the Louisbourg Grenadiers. He had been exposing himself recklessly throughout the French advance, and within minutes he had been wounded three times. The first shot that hit him shattered his right wrist. He wrapped his handkerchief around it and continued to press on. Shortly afterwards, he was hit by a second shot, which struck him in the groin. The bullet may have already spent its penetrating power because of the range, since Wolfe continued to move about freely. He was still leading the advance when he was hit by a third shot, which struck him squarely in the chest. This wound ultimately led to his death shortly afterwards.[1]

Library and Archives Canada Image, MIKAN No. 2897297)

Death of General Wolfe on the Plains of Abraham. 1857 engraving.

According to Brigadier George Townshend’s dispatch, the shot that killed General Wolfe did not come until after the famous volley. He wrote, “our General fell at the head of Braggs (the 35th) and the Louisbourg Grenadiers advancing with their Bayonets.” Whether it was a chance shot, or was aimed deliberately, “it was likely to have come from a marksman on the edge of the cliff above the St. Lawrence.”[2]

[1] Oliver Warner, With Wolfe to Québec, p. 167.

[2] Ibid, p. 167.

Death of General Wolfe. Painting by Benjamin West.

(Klaus-Dieter Keller Photo)

Statue of James Wolfe, by Robert Tait McKenzie 1927, on a hill in Greenwich Park, London.

General Montcalm wounded but still mounted on his horse, is brought back to Quebec after being wounded at thee Battle of the Plains of Abraham, 13 September 1759. Illustration for La Nouvelle-France by Eugene Guenin (Hachette, 1900).

Montcalm, still on horseback, was borne with the tide of fugitives towards the town. As he approached the walls a shot passed through his body. “Montcalm’s wound was in the stomach. It had probably been caused by grape-shot from one of Colonel Williamson’s two brass 6-pounders, for he had been a conspicuous target as he rode, drawn sword in hand, urging on his infantry.” He kept his seat, while two soldiers supported him, one on each side, and led his horse through the St Louis Gate of Québec, where a group of women replaced the escort of soldiers.[1] A woman who recognized him screamed, “O mon Dieu! mon Dieu! le Marquis est tué!” [“My God! My God! The Marquis is shot!”][2]

“Ce n’est rien, ce n’est rien,” answered the general, “ne vous affligez pas pour moi, mes bonnes amies.” [“It’s nothing, it’s nothing,” replied Montcalm, “don’t be troubled for me, my good friends.”][3]

[1] Francis Parkman, Montcalm and Wolfe, p. 478.

[2] Oliver Warner, With Wolfe to Québec, p. 170.

[3] Ibid, p. 170.

When he was brought wounded from the field, he was placed in the house of the Surgeon Arnoux, who examined the wound and pronounced it mortal. “So much the better,” he said, “I am happy that I shall not live to see the surrender of Québec.” He is reported to have said, since he had lost the battle it consoled him to have been defeated by a brave enemy. Some of his last words were in praise of his successor, Lévis, for whose talents and fitness for command he expressed high esteem. He thought to the last about those who had been under his command, and sent a note to Brigadier George Townshend:

“Monsieur, the humanity of the English sets my mind at peace concerning the fate of the French prisoners and the Canadians. Feel towards them as they have caused me to feel. Do not let them perceive that they have changed masters. Be their protector as I have been their father.”[1]

Montcalm died peacefully at 4 o’clock on the morning of the 14th. He was 48 years old. (He was buried in a shell crater under the floor of the Ursulines’ chapel). It has been said, “the funeral of Montcalm was the funeral of New France.”[2]

François-Gaston, duc de Lévis, Chevalier de Lévis.

“The Chevalier de Lévis came post-haste from Montréal when he received word of the defeat, assumed command, and set about restoring order. Despite the valiant efforts of Lévis and the reorganized forces he now commanded, Vaudreuil, over the protests of Lévis, was obliged to capitulate the following September to General Jeffrey Amherst at Montréal.”[3]

[1] Francis Parkman, Montcalm and Wolfe, pp. 485-486.

[2] Ibid, p. 486.

[3] W.J. Eccles, Montcalm, The Encyclopedia Canadiana, p. 467.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3330889)

Monument to Montcalm on Plains of Abraham, 1911.

After the Battle

As for the aftermath of the battle on the Plains of Abraham, the French losses were placed by Vaudreuil at about 1,640, and by the English official reports at about 1,500. Measured by the numbers engaged the battle of Québec could be described as a heavy skirmish; measured by the results, it was one of the great battles of the world.[1] Morison, however, reports that “each side suffered about equal losses, 640 killed and wounded.”[2]

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 2896918)

A view of the damage to the Church of Notre Dame de la Victoire, Quebec, 1760.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 2896917)

A view of the damage to the Treasury and the College of the Jesuts, Quebec, 1760.

Although Québec promptly surrendered to the British, Canada was soon cut “off from Europe by ice. In the spring of 1760, a reorganized French and Canadian army under the Chevalier de Lévis moved against Québec. Brigadier General James Murray, commanding a small, half-starved British garrison in the city, managed to hold them off.”[3] The outcome could not be completely decided until either the French or English navy arrived with supplies and supporting forces. Because the ice blocked access to Québec by either side’s reinforcements, much depended on whose fleet got through first. The first warship to arrive on the 9th of May 1760 was British, the frigate Lowestoffe. She was followed within a week by the Vanguard, a ship-of-the-line and by a second frigate, thus sealing the fate of New France. Chevalier de Lévis abandoned his siege on Québec and fell back to Montréal. “On the 8th of September 1760, after Generals Jeffrey Amherst, William Haviland and James Murray had invested Montréal, Governor the Marquis de Vaudreuil-Cavagnal, deserted by many French regulars and the Canadian militia, surrendered the whole of Canada to Great Britain.”[4] De Lévis moved to Ile Ste. Helene and his men burnt their colours and cut them up so that the British would not take them.[5]

[1] Francis Parkman, Montcalm and Wolfe, p. 474-486.

[2] Samuel Eliot Morison, The Oxford History of the American People, p. 168.

[3] Ibid, p. 168.

[4] Ibid, p. 169.

[5] Internet. http://odur.let.rug.nl/~usa/E/7yearswar2/7years03.htm, p. 2.

[6] Fred Anderson, A People’s Army, p. 21.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 2837481)

Illustration of the Battle of Sainte-Foy), 28 April 1760.

In April 1760, François Gaston de Lévis led French forces to launch an attack to retake Quebec. Although he won the Battle of Sainte-Foy, Lévis’ subsequent siege of Quebec ended in defeat when British ships arrived to relieve the garrison. After Lévis had retreated he was given another blow when a British naval victory at Restigouche brought the loss of French ships meant to resupply his army. In July Jeffrey Amherst then led British forces numbering around 18,000 men in a three pronged attack on Montreal. After eliminating French positions along the way all three forces met up and surrounded Montreal in September. Many Canadians deserted or surrendered their arms to British forces while the Native allies of the French sought peace and neutrality. De Lévis and the Marquis de Vaudreuil reluctantly signed the Articles of Capitulation of Montreal on 8 September which effectively completed the British conquest of New France.

(Musee Virtuel Illustration)

French authorities surrendering Montréal to British forces in 1760.

Governor Vaudreuil in Montreal negotiated a capitulation with General Amherst in September 1760. Amherst granted his requests that any French residents who chose to remain in the colony would be given freedom to continue worshiping in their Roman Catholic tradition, to own property, and to remain undisturbed in their homes. The British provided medical treatment for the sick and wounded French soldiers, and French regular troops were returned to France aboard British ships with an agreement that they were not to serve again in the present war.

Most of the fighting ended in America in 1760, although it continued in Europe between France and Britain. The notable exception was the French seizure of St. John’s, Newfoundland. General Amherst heard of this surprise action and immediately dispatched troops under his nephew William Amherst, who regained control of Newfoundland after the Battle of Signal Hill in September 1762.

The French surrender ended the war in Canada after six years of hard fighting. Great celebrations were held in Massachusetts and everywhere its soldiers served on hearing the news.[1]

[1] Fred Anderson, A People’s Army, p. 21.

The Seven Years War officially ended on the 10th of February 1763 with the Treaty of Paris, which was signed to settle differences between France, Spain, and Great Britain. Among the terms was the acquisition of almost the entire French Empire in North America by Great Britain. The British also acquired Florida from Spain and the French retained their possessions in India only under severe military restrictions. The continent of Europe remained free from territorial changes.

At the close of the Seven Years War with the Peace of Paris in 1763, “no living soul in Massachusetts could foresee the coming separation from Great Britain, and no one desired it.” With the conclusion of the war in 1763, American commitment to the empire reached its zenith. The people of Massachusetts would have been pleased to be part of the British system and equally proud to have participated in the British triumph. Their heroes were William Pitt and Jeffrey Amherst, Viscount Howe, and James Wolfe. During the war and in its aftermath, settlements were named in honor of Pitt in Massachusetts and Amherst in Nova Scotia.

It is a strange twist of history indeed, that within a dozen years veterans of the Seven Years War would again take up arms in 1775, to fight the British redcoats, many of whom they would have served alongside at battle fields such as Ticonderoga, Louisbourg and Quebec.

Aftermath

The Seven Years’ War had a significant effect on the future of Canada for two important reasons. North America had both English and French settlers. Initially, the British wanted the French settlers in Quebec to adopt English customs. Laws were written in English, and Catholics, who mostly spoke French, weren’t allowed to have government jobs. Within a very few years it became obvious that this approach wasn’t working, and in 1774, the ruling government created a law called the Quebec Act, which gave people in Quebec freedom of religion and the right to use some French laws. This was the beginning of Canada as a legally bilingual and bicultural nation.

The war also changed the relationship between Britain and First Nations living in what would become Canada. After the war, King George III made a new law called the Royal Proclamation of 1763. Uritain didn’t control in North America belonged to the Indigenous people who lived on it. Indigenous peoples could keep those lands unless they wanted to sell them to the King. This meant that only the British government could buy land and make treaties with Indigenous nations. This law is still an important part of the Government of Canada’s relationship with Indigenous peoples today.

One hundred and fifty years of French-British conflict in North America ended in the Seven Years’ War. It led to the creation of Canada as we know it today. (The Canadian Encyclopedia)