Sieges, Part 4, Age of Gunpowder

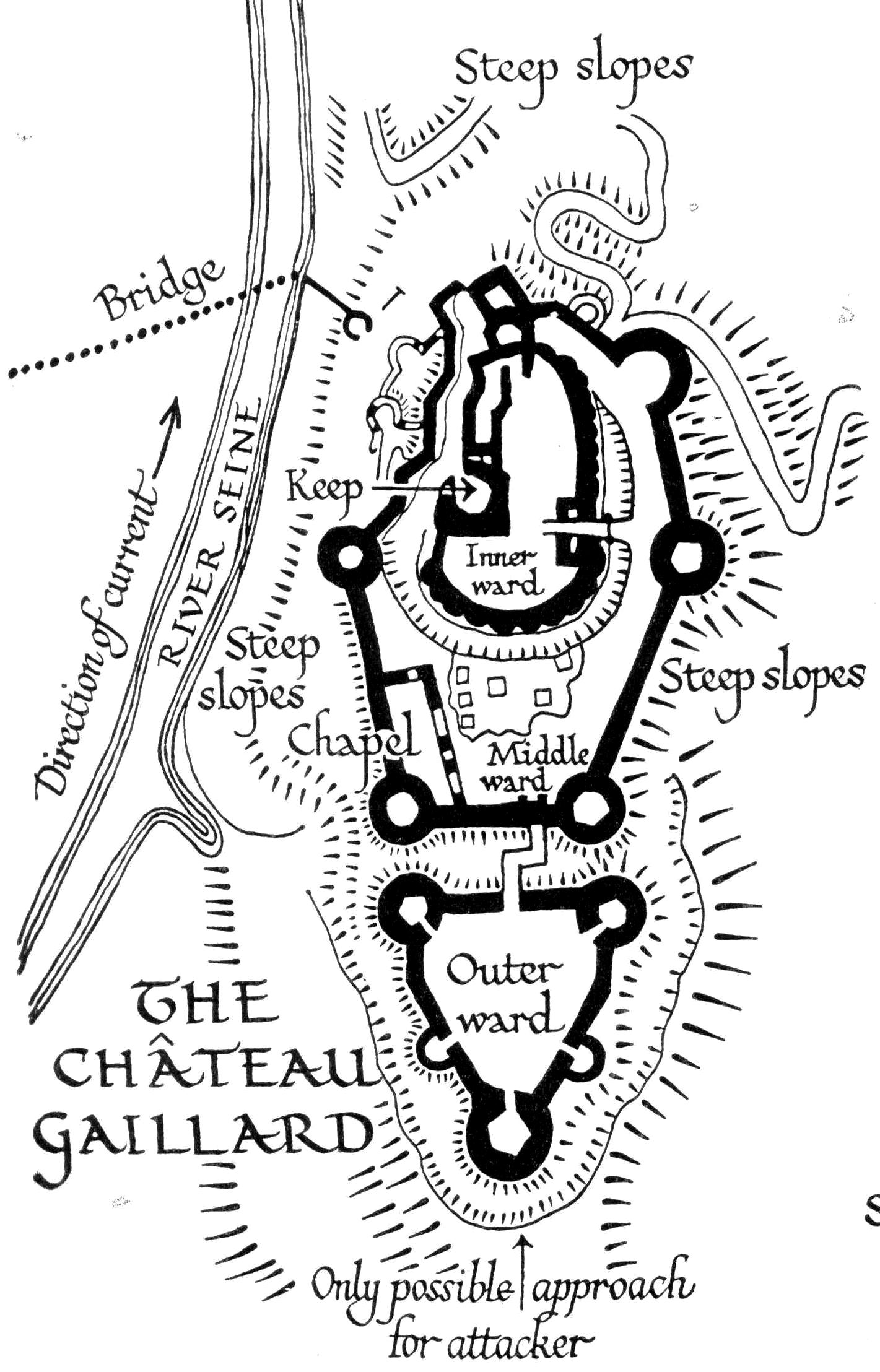

Siege of Château Gaillard, 1203-1204

(Sylvain Verlaine Photo)

Aerial view of Château Gaillard.

Plan view of Château Gaillard.

Richard Coeur de Lion’s career dramatizes the military trends and siege methods of his day. When he returned from the Crusades he began to apply the principles he had learned to castles he built in France. It has also been said that Syrian workmen were imported to build his most famous castle, the Château Gaillard.[148]

Château Gaillard, one of Europe’s earliest examples of rounded keeps and concentric fortifications and sighted to dominate Rouen in Normandy, was besieged in 1203-4 by Philip II. The siege of this famous Château come about as a result of the long struggle between the Angevin and Capetian kings in the 12th century. The rivalry was brought to a head when Richard built Château Gaillard in order to compensate for the loss of Gisors, which had been ceded to Philip by the Treaty of Issoudun in 1195.[149]

(Nitot Photo)

Chateau de Gisors. When Richard built the stronghold in 1197 he introduced the design of outer wards and foreworks beyond the main walls. The castle had a strong keep and occupied a well chosen strategic position on a steep height defending Rouen, the capital of Normandy, from every direction. The outer defenses included a bridgehead covering the Seine. Although Richard believed his fortress was impregnable, he never had the chance to prove it, as he was mortally wounded by a crossbow shot in 1199 during a minor siege at Chalus. The defense of the Château therefore fell to Richard’s brother John, who was no match for Philip.[150]

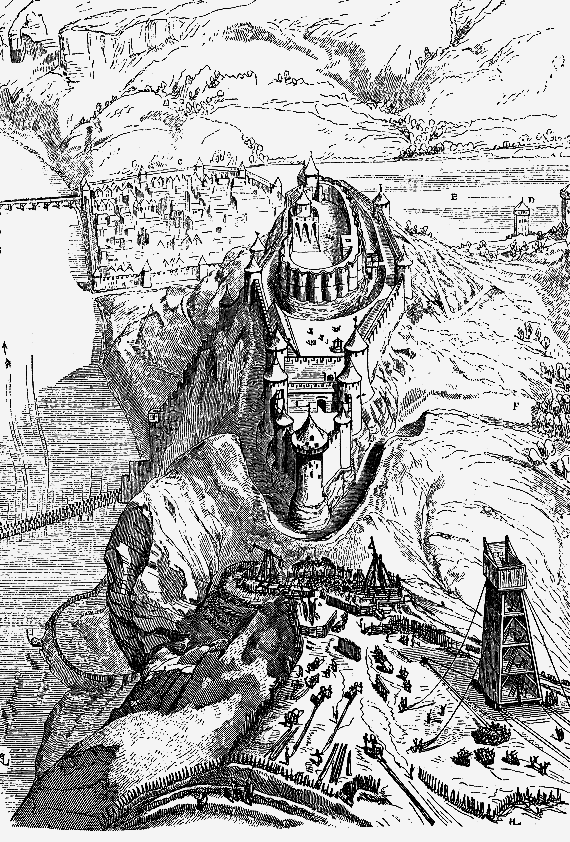

An impression by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, a 19th-century architect experienced in renovating castles, of how the Siege of Château Gaillard would have looked.

In August 1203 Philip brought a great army with him, to lay siege to Château Gaillard as the first stage in his conquest of Normandy. Philip gained an almost immediate success in destroying Richard’s elaborate system of defenses across the Seine. Strong swimmers broke up a palisade built across the river, and a fort on the island was taken. Another swimmer who had carried a sealed pot of coals managed to burn down a wooden stockade around the township of Les Andelys. The unfortunate citizens fled into the castle. The only offensive by John’s forces was a night attack, which failed miserably. In September, Philip built double lines of circumvallation and sat down to wait.

The garrison of Château Gaillard was capably commanded by constable Roger de Lacy, with 40 knights, 200 foot sergeants, and about 60 engineers and crossbowmen. Hundreds of refugees however, had fled to the shelter of the castle on the approach of the French forces. To save his supplies, de Lacy expelled many who were allowed to pass through the French lines. A second wave of about 400 were not, however, allowed to pass through by the French, who hoped de Lacy would take them back. De Lacy refused to do so, and these unfortunate people had to spend the winter outside the castle, in between the warring factions and in danger of missiles from both sides. When Philip finally relented and let them through, it was too late for most of them, as they died of the effects of starvation and exposure. The blockade went on for six months.

By February 1204 the French towers and siege-engines were ready and the assault began. Ground was leveled and materials were brought up to fill in the castles protective ditch. Catapults and siege towers were constructed on site, and hurried into action. Both sides employed picked marksmen. The first success, however, went to the miners. While working under the cover of mantelets for protection, they picked holes in the foundation of the curtain wall of the outer bailie, and set fire to wooden props, which caused the wall to collapse. The defenders burned everything behind them and retreated to the next obstacle. This was a 30’ deep ditch forward of the inner bailie, whose walls rose flush from the ditch and gave no purchase for the miners.

The siege would have dragged on for some time, but a small group of Philip’s soldiers suddenly noticed that a latrine shaft was open on the west side of the castle just below an unbarred window of the castle chapel. One man managed to crawl up the drain of the privy, entered the chapel, and reached the window through which he pulled up other soldiers. There they raised an uproar, which made the defenders believe a great many of them had gained entrance. In the ensuing confusion they managed to get to the drawbridge and let it down. The defenders failed in an attempt to smoke them out, panicked, and fled to the safety of the inner bailie. The paradox is that it was John who had added the chapel, and had thus introduced a weakness into Richard’s design.[151]

Siege engines made no impression on the walls of the inner bailie, which had an odd scalloped design that made it particularly difficult for the miners to attack. There was however, one place under a stone bridge, which afforded them some protection. Philip brought in a great catapult named Cabalus to reinforce their efforts. The defenders made a brave attempt at counter-mining but their efforts only weakened the wall further without driving off the attackers. There was a huge fall of masonry and the defenders, not even bothering to retreat to the keep, tried to flee by a postern gate where they were met and forced to surrender.

The unusual strength of Philip’s army, and the length of the winter siege were the important factors in the castles fall, rather than the design of the fortress. It would not have fallen if adequate steps had been taken for its relief.[152] The seizure of Normandy rapidly followed the fall of Château Gaillard, and Philip Augustus eventually gained the Angevin Empire.[153]

(Bill Taroli Photo)

Mural of seige warfare Genghis Khan Exhibit, Tech Museum, San Jose.

In the 13th century, the Mongols invaded Europe.[154] They had developed a cold and efficient method of siegecraft based on their extensive battlefield experience.[155] Their system made use of secret agents who took advantage of cowardice or treachery. If they failed, the next step was a blockade and bombardment by their war engines, whose essential parts were carried on packhorses. Finally, if a city could not be betrayed, battered or starved into submission, a continuous day and night attack was carried on by troops serving in relays.[156]

Mongols Besieging A City In The Middle-East, 1 Jan 1307.

The Mongols themselves had no illusions as to their own invincibility, and their primary interest was in plunder. The wooden castles and log palisades of Russia, Poland and Hungary offered few difficulties for them, but the remainder of Europe was principally a terrain of forests and mountains, of miserable roads and massive stone fortifications. The invaders, it appears, prudently took note of these obstacles, and decided not to venture outside their own tactical element.[157]

Polish soldiers armed with early firearms, 1674-1696.

Simple handguns first began to appear in the second quarter of the 14th century, in the form of short tubes of brass or iron closed at one end. Near the closed end, the breech was pierced by a small hole through which the charge could be fired with a piece of burning slow-match or tinder. This barrel could be fixed to the end of a wooden staff and aimed rather roughly, by tucking it under the arm, or by supporting it on a rest. In either case, the rear end of the staff could be stuck into the ground to take the recoil.[158]

Swiss soldier firing a hand cannon, with powder bag and ramrod at his feet, c. late 14th century (produced in 1874)

Handguns were reportedly in use at the Battle of Crécy in 1346, and again at Agincourt in 1415, but without noticeable effect or influence on the outcome of either battle.[159] In 1521 France’s Francis I went to war with the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, making use of guns with six-foot long barrels and one-inch bores. The French infantry used these long-barreled firearms to rake the parapets of Charles’ castles, forcing the defenders to take cover.

Hand-held firearms

Early handgunner.

The manufacture of firearms and cannon was an expensive business. In most cases, only kings or powerful overlords with considerable financial resources at hand could afford to have them made in numbers substantial enough to make a difference in a major siege or battle. Once they did have them, however, the effects could be devastating. In 1494, France’s Charles VIII invaded Italy, bringing with him a siege train that included 40 bronze cannon with barrels eight feet long. These guns were easily elevated or depressed because they moved on two prongs or trunions placed just forward of the barrel’s balancing point. Except for the heaviest, these cannon were easily moved by lifting the trail of the gun mount and shifting it to one side or the other. They fired iron balls at ranges equal to those of earlier cannon that were three times their caliber. Charles guns were transported on carriages that increased their ease of mobility. His cannon struck the Italian fortresses with an effect that resembled German Blitzkrieg warfare of the Second World War. The Italian fortress of San Giovanni had once been besieged for seven years. The French gunners destroyed it in eight hours and then slaughtered the defending garrison. The era of the long siege was closing, but would never be completely eliminated.

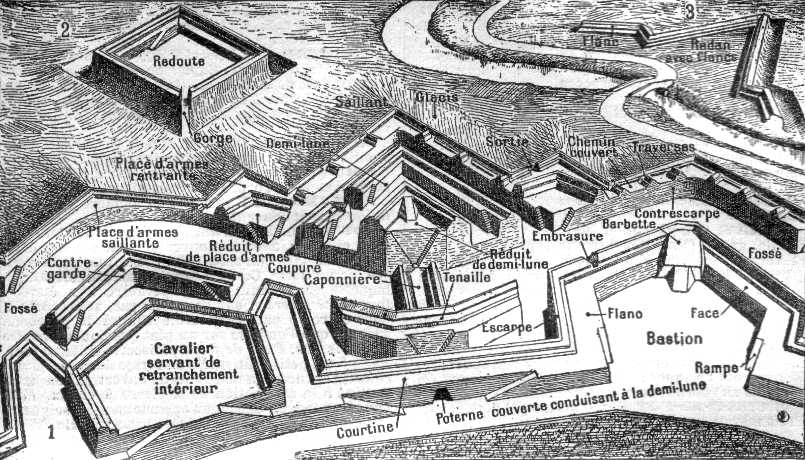

Engraving showing Bastions and elements of fortifications from the Vauban era.

To counter the increase in firepower, new designs in fortification were developed. Squared castle designs gave way to the lower silhouette of the square fort with corner bastions which were constructed to support a pro-active defense. The post-gunpowder era fortresses had to have walls thick enough to absorb cannon fire, and sloped enough to counter scaling. The bastions had to be sited to ensure there was no dead ground where an attacker go undermine the wall or otherwise get close to it unobserved. Inventive minds did not necessarily restrict themselves to designing fortresses using only increased stonework. Vauban and other fortress designers incorporated log and earthwork components into their outer walls to absorb cannon fire. When the Spanish attacked the fortress at Santhia in 1555, its multi-layered and reinforced earth walls reportedly absorbed some 6,300 artillery rounds over three days with suffering major damage. This put the onus back on the designer of siege weapons to develop new tactics, or to increase the capability of his cannon and firearms.

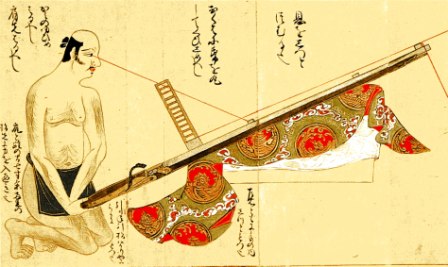

Japanese matchlock sighting instructions for indirect fire.

The increase in the availability of technologically advanced weapons played a major role in this change, and as will be shown in the following chapter, at the siege of Orleans, gunpowder took a leading part.

Siege of Orleans, 1428

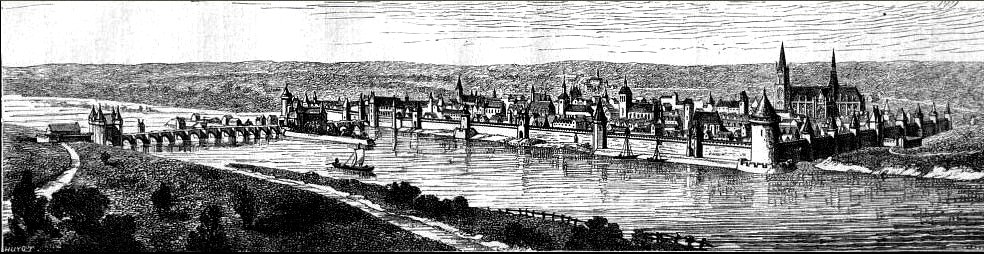

Orléans in September 1428, the time of the Siege.

The ancient city of Orleans on the Loire had withstood many assaults since the days of the Romans, including an attempt by Attila’s Huns in 451.[160] It came under siege during the Hundred Years War (1339-1453) when the French were trying to drive out the English forces. Orleans was protected by walls six feet thick, which rose from 13 to 33 feet above the moat, while five gates and 34 towers completed a system of outer defenses topped by stone battlements and parapets. In addition to war engines of all sorts, the city had provided itself with 70 mortars, bombards (heavy siege guns) and culverins. This may have been one of the most impressive concentrations of artillery ever seen in the Middle Ages, since many of the pieces were borrowed from other towns.

Siege of Orleans, 1429, Dunois defends thecity walls against the English, 1429. Dictionnaire populaire illustréd’histoire, de géographie, de biographie, de technologie, de mythologie,d’antiquités, des beaux-arts et de littérature, rédigé et édité par Edmond Alonnier& Joseph Décembre, tome 2, Paris : Imprimerie parisienneDictionnairepopulaire illustré d’histoire, de géographie, de biographie, de technologie, demythologie, d’antiquités, des beaux-arts et de littérature, rédigé et éditépar Edmond Alonnier & Joseph Décembre, tome 2, Paris : ImprimerieParisienne Illustration)

(Greenshed Photo)

English bombards abandonded by Thomas Scalles at Mont Saint-Michel on 17 June 1434. Calibre 380 – 420.

Orléans, was one of the towns Joan of Arc (1412-1431) defended from the English during the Hundred Years War (1337-1453). In the city’s defence, she was overwhelmingly successful, but her exploits did not stop there. In just over a year, this teenager led troops in 13 different battles and sieges, and captured more than 30 cities.

(Illustration by Paul Lehugeur 1854-1916)

Joanof Arc leading a siege on a city in the 15th Century.

Joan of Arc at the Siege of Orléans, painting by Jules Lenepveu.

A strong garrison manned the city when an English army of about 4,000 appeared in October 1428, with a siege train of mortars and bombards drawn by oxen. The first act of the assailants was to conscript the labor of the district to build two huge stone and wood bulwarks. These would be used later to storm the walls of the city.

During the siege, the town’s normal population of 15,000 swelled to 40,000 people, most of them men-at-arms or refugees from outlying regions. Tempers were worn thin by overcrowding, and constant friction occurred between the townsmen and soldiers. Despite a gross lack of sanitary precautions, Orleans managed to escape the usual epidemic. The English blockade could not prevent merchants from entering the gates with grain, cattle and gunpowder. This in fact put the besiegers in a worse position than the defenders, since they did not have adequate food and supplies.

The women and children were tasked with the manufacture of the thousands of darts and crossbow bolts that were shot from the battlements. Twelve master gunners, with many apprentices and laborers to do their bidding, served the myriad instruments of destruction employed by the city. For their part, the English managed several times to launch large stone balls weighing 150 pounds into the city, causing considerable destruction.

Despite such exceptions, the artillery of 1429, while potent against smaller strongholds, had not yet become a threat to walled cities of any strength. Attrition was the only result of the seven-month gunnery duel at Orleans. From the beginning of the battle, the material advantage had been on the side of the defenders, who were superior in numbers, guns and supplies. Orleans might still have fallen due to low morale, were it not for the appearance of Joan of Arc.[161] Her very innocence of military affairs proved an incentive to burghers who distrusted their own men-at-arms. They rallied behind her and stormed by sheer weight of numbers the two English bulwarks commanding the walls. After severe losses, the invaders lifted the siege in May 1429, and retreated in the conviction that they had been overcome by sorcery.[162] Joan was eventually captured by Burgundians and sold to the English.[163] She was put on trial and burnt at the stake in Rouen.[164]

Although the siege of Orleans was not successful, the use of gunpowder was to set the tone for most of the sieges that followed. The Wars of the Roses (1455-1485) saw many sieges involving firearms.[165] During the Hussite Wars (1419-1436) the Hussites adopted a distinguishing feature of battle in their employment of the wagon-fort as the unit of tactics. These wagon-forts could more accurately be described as an armored car pierced with loopholes for crossbows and handguns. Twenty warriors were attached to each unit, half of them pikemen who manned the gaps between vehicles to guard against cavalry assault. In line of battle, a ditch protected the front of wagon-forts linked by chains, though both drivers and horses were also trained for offensive maneuver. Contemporaries have left a legend of complex movements executed at a gallop, but the results indicate that mobility was not sacrificed with the use of the heavy iron cover on the cars.

(PHGCOM Photo)

Hand bombard, 1390–1400, Musee de l’Armee, Paris.

(PHGCOM Photo)

200 kg wrought iron bombard, circa 1450, Metz, France. It was manufactured by forging together iron bars, held in place by iron rings. It fired 6 kg stone balls. Length: 82 cm.

The handgun was most effective, and the Bohemian leader Ján Zizka armed one third of his infantry with this weapon. Here, the mobility of the wagon-fort had its tactical effect, since the rolling fortresses permitted cool and deliberate aim by sheltered men firing from a rest. Ziska was also the first to maneuver with artillery in the field, using heavy bombards of medium calibre. All of his cannon were mounted on four-wheeled carts which could be brought up into the gaps between wagon-forts for a concentration of fire upon any part of the enemy’s line. Stone balls weighing upwards of 100 pounds were thus sent with deadly effect into massed squadrons of feudal cavalry. In 14 years, Ziska’s tactics had won at least 50 battles, while accounting for the sack of 500 walled towns or monasteries, all without suffering a single noteworthy defeat.[166]

The armies of France were not slow to perceive the possibilities of artillery firepower, and the gun founders of the country soon led in creative experiment. In 1494, Charles VIII of France invaded Italy with a siege train that included 40 bronze cannon with barrels eight feet long, mounted on carriages to increase their mobility. These guns were used to destroy the fortress of San Giovanni, once besieged for seven years, in only eight hours.[167] The first significant effect of firearms then, was not to increase firepower on the battlefields, but to destroy the immunity of fortresses.[168]

Gunpowder may have originated in China where it was used in the production of fireworks, but the Europeans appear to have been the first to make use of it in firearms, as this is where the Chinese imported them from during the 1400s. The English Franciscan monk Roger Bacon described a formula for gunpowder in the early 14th century, which consisted of “seven parts saltpeter, five of young Hazelwood (charcoal), and five of sulphur.” It proved to be effective, for when this compound of traditional black powder is ignited, it expands to 4000 times its volume in a very short period of time. Small arms (firearms used by a single soldier) possibly came into use by 1284. By 1326, the city of Florence was paying for the construction of cannon and the manufacture of gunpowder. In 1331, cannon were used at the siege of Cividale in Italy, and by 1339, the first cast guns were being made. These guns were initially cast using the same techniques used to cast church bells. Artillery weapons were cast with bronze, a material with a low melting point and considerable toughness.[169]

Advances in the technique and use of the weight, power and destructive capability of artillery quickly led to the development of stronger and more effective fortifications. Most of the early works were Italian. Artists such as the Sangallo family working out of Rome, Leonardo da Vinci, and Michelangelo brought their fertile imaginations to fortress design. In Germany, the painter and printmaker Albrecht Durer contributed new designs. These designs in turn pointed the way towards the development of the military engineer as a specialist in his own right.[170] Engineering however, would not save the city of Constantinople in 1453 as we shall see in the next chapter.

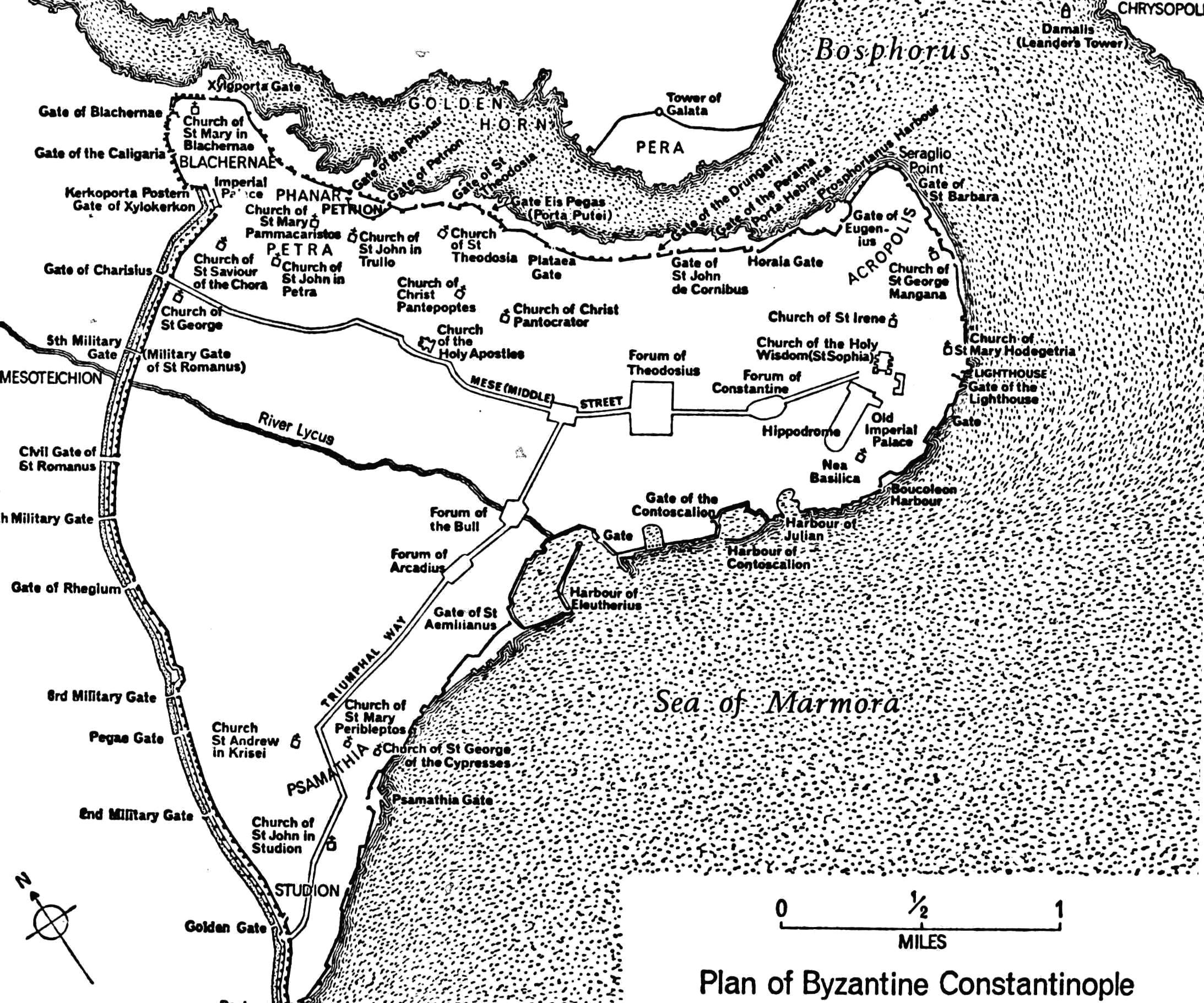

Siege of Constantinople, 1453

Constantinople had been heavily fortified since the sixth century with a strong system of triple walls, augmented with a moat 60 feet wide and 20 feet deep. The moat could be filled with water, which was piped from distant hills, although it was generally used as a dry ditch. Behind the scarp, a battlemented wall six feet high was constructed to provide cover for archers. Sixty feet behind this obstacle rose another wall 27 feet high, which was studded with 96 towers, which projected over the wall in such a manner that they were able to permit flanking fire. These towers were spaced 180 feet apart, and varied in height from 30 to 35 feet above the wall.

The third great wall was connected to the second by a covered way. This allowed the safe passage of troops, was 30 feet high and nearly as thick, and had a rear drop of 40 feet to the level of the city. Protruding from this barrier was another system of 96 towers, which in turn were twice the height of the second wall, and laid out in a checkerboard fashion along the wall.[171]

In spite of their strength, the walls fell to the armies of the Fourth Crusade. The defending garrison beat off wave after wave of attackers, but the Crusaders made good use of the torch. Advancing behind the flames, they had barely secured a foothold, when the Varangian Guards, the best troops of the city, chose this moment to demand arrears in pay.[172] With added to the fire, the morale of the defenders collapsed and Constantinople fell on 7 April 1203.[173]

The Ottoman Turks transport their fleet overland into the Golden Horn, painting by Kusatma Zonaro.

The defenses of Constantinople survived, but in 1453 there was only a small garrison of troops to defend the city when a Turkish army arrived to take it. Constantinople was defended by 7000 troops under (Giovanni) Giustiiniani. The Turks dragged 70 light ships one mile overland to by pass a heavy iron chain across the Golden Horn, completely blockading the city. On 18 Apr 1453 Turkish Sultan Mohammed II (Mehmet II) began to use 70 cannon and 80,000 troops to besiege and capture the city of Constantinople, which he succeeded in doing after a series of attacks on 7, 12,and 21 May 1453. The Major assault came on 29 May when 12,000 Jannisary Infantry stormed the gates. A key role was played by the artillery.

Sultan Mehmed II and the Ottoman Army approaching Constantinople with a giant bombard, painting by Fausto Zonaro.

(The Land Photo)

The Dardanelles Gun, a very heavy 15th-C bronze muzzle-loading cannon of type used by Turks in the siege of Constantinople in 1453, showing ornate decoration. It is currently on display at Fort Nelson, Hampshire, UK. (The Land Photo)

The siege resolved itself into a contest between the new weapons of gunpowder and Europe’s mightiest system of fortifications. Even in their decline, the walls were more formidable than any masonry yet conquered by cannon, although the Turks brought a siege train of 70 pieces which also merited comment. One of their enormous weapons was a bombard named Basilica. Drawn by 60 oxen, it fired a stone ball weighing 800 pounds. This monster cracked after a few days, but eleven other bombards continued to send projectiles crashing into the outer works. At first the Turkish artillery made the mistake of firing at random, hoping to make a few lucky hits. It initially appeared that the defenses might resist this hammering, but the repeated battering by the weighty stone balls eventually shook the defenses and even breached them in places. As they gained experience, the besiegers learned how to direct their fire more efficiently, and to concentrate their cannon fire against a previously selected section of the wall.[174]

After 40 days four towers were leveled and so many breaches had been opened that a general land and sea assault succeeded in a few hours. The fall of Constantinople proved that the mightiest walls were no longer safe against gunpowder.[175] (Constantinople was renamed Istanbul in 1930).

Plan view of the City of Constantinople at the time of the Turkish assault.

The evolution forced military architects to design defenses that were dug in for protection instead of building upward to create targets.[176] Defenses had to be made strong enough to withstand not only the battering of an enemy’s cannon, but allow adequate support for the mounting of bigger and better forms of artillery on the battlements of the defender.

The Turkish Sultan Suleiman the magnificent appeared with a large army before Shabetz in 1521 and carried the walls by storm. Marching 40 miles east, where Belgrade commanded the junction of the rivers Danube and Save, the Muslims bridged the latter and cut the great fortress off from supplies or reinforcements. Belgrade, like Shabetz, was woefully undermanned, and the Turkish sappers created breaches by means of gunpowder mines. The inevitable surrender, after a resistance of a few weeks, found only 400 able-bodied defenders in the citadel.

Sultan Mehmed II’s entry into Constantinople, painting by Fausto Zonaro.

For the next few years, Suleiman turned to developing a Muslim navy, with the intention of seizing control of the Mediterranean Sea. His next expedition was against Rhodes, the last great outpost of Christendom in the Aegean, and reputedly the world’s strongest fortress.

Reconquista, 1492

The Reconquista (reconquest) is a Spanish and Portuguese term used to describe the period in the history of the Iberian Peninsula of about 780 years between the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in 711 and the fall of the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada to the expanding Christian kingdoms in 1492. The completed Reconquista was the context of the Spanish voyages of discovery and conquest (Colón got royal support in Granada in 1492, months after its conquest), and the Americas, then known as the “New World”, ushering in the era of the Spanish and Portuguese colonial empires.

Western historians have marked the beginning of the Reconquista with the Battle of Covadonga (718 or 722), one of the first victories by Christian military forces since the 711 Islamic conquest of Iberia by the Umayyad Caliphate. In that small battle, a group led by the nobleman Pelagius defeated a caliphate’s army in the mountains of northern Iberia and re-established the independent Christian Kingdom of Asturias. The Spanish reconquest reached a climax with the fall of Seville in 1248 and the submission of the Moorish kingdom of Granada as a Castilian vassal state.

During the Reconquista, the Spanish captured and enslaved the Moors (North African Muslims) as new territories were liberated by advancing forces. The practice that developed during this extensive campaign against the Muslims, granting privileges (encomienda rights) to certain Christian warriors (adelantados) who reestablished Spanish control, was the same system that was later modified and employed to subjugate indegenous populations in the Americas.

Crusader privileges were given to those aiding the Templars, the Hospitallers, and the Iberian orders that merged with the orders of Calatrava and Santiago. The Christian kingdoms pushed the Muslim Moors and Almohads back in frequent Papal-endorsed Iberian Crusades from 1212 to 1265. By 1491, the city of Granada itself lay under siege. On 25 Nov 1491, the Treaty of Granada was signed, setting out the conditions for surrender. On 2 Jan 1492, the last Muslim leader, Muhammad XII, known as Boabdil to the Spanish, gave up complete control of Granada, to Ferdinand and Isabella, the Catholic Monarchs, at which point the Muslims and Jews were finally expelled from the peninsula.

The surrender of Granada, 1492, painting by Pradilla.

The Christian ousting of Muslim rule on the Iberian Peninsula with the conquest of Granada did not extinguish the spirit of the Reconquista. Isabella urged Christians to pursue a conquest of Africa. About 200,000 Muslims are thought to have emigrated to North Africa after the fall of Granada. Initially, under the conditions of surrender, the Muslims who remained were guaranteed their property, laws, customs, and religion. This however, was not the case, causing the Muslims to rebel against their Christian rulers, culminating with an uprising in 1500. The rebellion was seen as a chance to formally end the Treaty of Granada, and the rights of Muslims and Jews were withdrawn. Muslims in the area were given the choice of expulsion or conversion. In 1568–1571, the descendants of the converted Muslims revolted again, leading to their expulsion from the former Emirate to North Africa and Anatolia. For Jews as well, a period of mixed religious tolerance and persecution under Muslim rule in Spain came to an end with their expulsion by the Christian monarchy in 1492. (Barton, Simon. A History of Spain. Palgrave Macmillan, 2004)

Siege of Rhodes, 1522

Siege of Rhodes, 1522, engraving by Guillaume Caoursin.

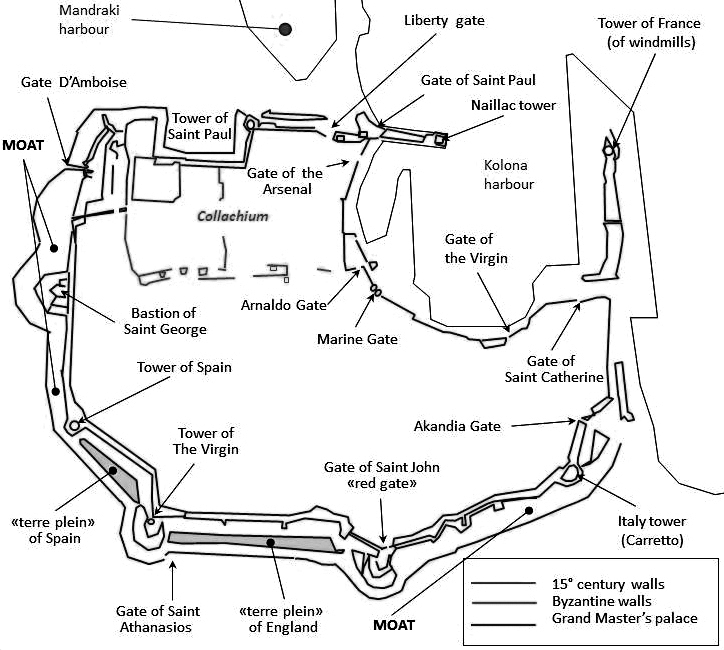

In 1522 the Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent prepared an expedition against Rhodes, the last great outpost of Christendom in the Aegean, and reputedly the world’s strongest fortress.[177] The Knights Hospitallers, as masters of Rhodes, had incorporated all of the leading improvements in defense-works into their fortress, at an enormous expenditure in time and money. Suleiman, however, crossed from the Asiatic shore with a great artillery train and an army of 150,000, which included a host of sappers from the mines of the Balkans. The siege of Rhodes was conducted throughout the summer and autumn of 1522, and proceeded to clearly prove the superiority of the new fortifications over the most powerful offensive of its time. Although the invaders brought huge mortars firing stone cannon balls, the bastion stood firm and returned a cannonade, which caused frightful losses among the assailants. The Turks excavated 54 gunpowder mines without gaining a permanent lodgment, being frustrated in most instances by countermines. In desperation, Suleiman made several attempts to carry Rhodes by storm, but few of his troops were able to penetrate beyond the shot-swept glacis and ditch.

(Norbert Nagle Photo)

Gate of Saint Athanasiou, Rhodes.

Rhodes fortifications, plan view.

(PHGCOM Photo)

Bombard-Mortar of the Knights of Saint John of Jerusalem, Rhodes, 1480-1500.

The fortress might have held out indefinitely except for a dire shortage of gunpowder, which in the end caused the Knights to accept the remarkably easy terms of victors whose losses were estimated as high as 60,000 slain. Ottoman sea power rather than siegecraft deserved the credit however, since neither Venice nor any other Christian state chose to risk a naval encounter with the blockading galleys.[178]

(Norbert Nagel Photo)

The English Post, the scene of heaviest fighting; the tenaille is on the left and the main wall is further behind it, visible in the background; on the right of the wide dry ditch is the counterscarp that the attackers had to climb down before storming the city wall. The ditch is enfiladed by the Tower of St. John, its bulwark and lower wall providing vertically stacked fields of overlapping fire. T he stone cannonballs seen in the ditch are from the fighting.

(Hannes Grobe Photo)

The Tower of Italy had a round bulwark built around by Grand Master Fabrizio del Carretto in 1515–17, and provided with gun ports at lowest level covering the ditch in every direction, for a total of three stacked tiers of cannon fire (two from the bulwark, one from the tower).

(Piotrus Photo)

The tower of St. John at the East end of the English sector. The tower was built under Grand Master Antonio Fluvian (1421–37), and it had a gate. Later a barbican was built around it under Grand Master Piero Raimundo Zacosta (1461–67). Finally the large pentagonal bulwark was built in front of it c. 1487, and the gate was removed.

Although the Knights had lost the Fortress of Rhodes, when Suleiman decided to attack them again in their new stronghold on Malta in 1565, they were better prepared.[179]

Kolossi Castle, Cyrpus

Kolossi Castle is a former Crusader stronghold on the south-west edge of Kolossi village 14 kilometres (9 mi) west of the city of Limossol on the island of Cyprus. It held great strategic importance in the Middle Ages, and contained large facilities for the production of sugar from the local sugarcane, one of Cyprus’s main exports in the period. The original castle was possibly built in 1210 by the Frankish military, when the land of Kolossi was given by King Hugh I to the Knights of the Order of St John of Jerusalem (Hospitallers)

(Michael Photo)

Kolossi Castle.

The present castle was built in 1454 by the Hospitallers under the Commander of Kolossi, Louis de Magnac, whose arms can be seen carved into the castle’s walls. Owing to rivalry among the factions in the Crusader Kingdom of Cyprus, the castle was taken by the Knights Templar in 1306, but returned to the Hospitallers in 1313 following the abolition of the Templars. The castle today consists of a single three-storey keep with an attached rectangular enclosure or bailey about 30 by 40 metres (98 by 131 ft).

As well as its sugar. the area is also known for its sweet wine, Commandaria. At the wedding banquet after King Richard the Lionheart’s marriage to Berengaria of Navarre at nearby Limassol, he allegedly declared it to be the “wine of kings and the king of wines.” It has been produced in the region for millennia, and is thought to be the oldest continually-produced and named wine in the world, known for centuries as “Commandaria” after the Templars’ Grand Commandery there.

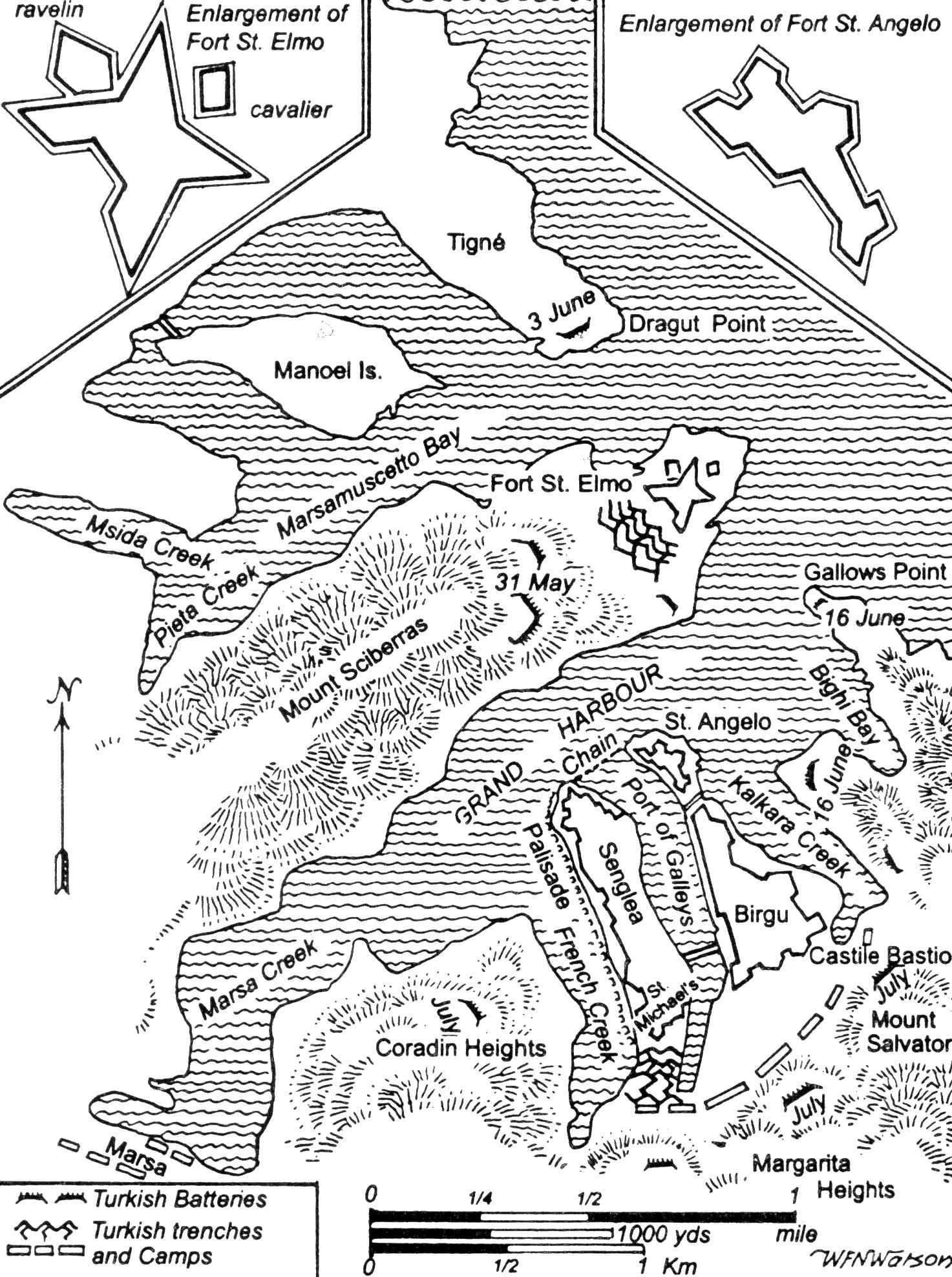

Siege of Malta, 1565

The Great Siege of Malta took place in 1565 when the Ottoman Empire tried to invade the island of Malta, then held by the Knight’s Hospitaller. The Knights, with approximately 2,000 footsoldiers and 400 Maltese men, women and children, withstood the siege and repelled the invaders. This victory became one of the most celebrated events in sixteenth-century Europe. The siege was the climax of an escalating contest between a Christian alliance and the Islamic Ottoman Empire for control of the Mediterranean, a contest that included the Turkish attack on Malta in 1551, the Ottoman destruction of an allied Christian fleet at the Battle of Djerba in 1560, and the decisive Battle of Lepanto in 1571.

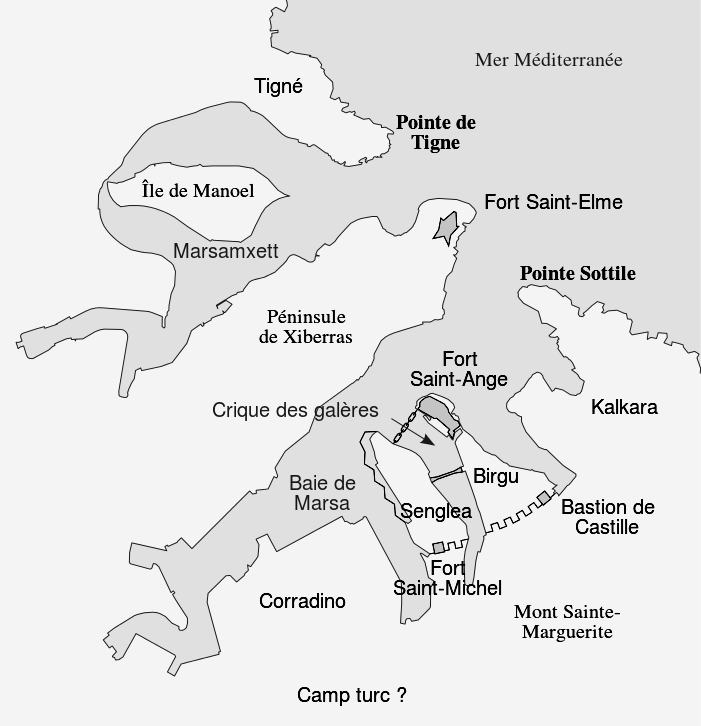

Plan view of the fortifications on Malta in 1565.

The island of Malta had command of the East-West trade routes and its strategic position could not be ignored. Once it was in Turkish hands, Suleiman could use the island as a base from which he could conquer Sicily and Southern Italy. A seaborne invasion was launched in the spring of 1565.[180]

Map of the Great Siege of Malta.

(5afd4770411ca76c Photo)

Fort Saint Angelo de la Valette on the Birgu peninsula.

The island had little to offer except for a good harbor, and much construction would be needed to build up its defenses. Although the capital, Medina, was initially poorly protected, the Fort Saint Angelo at the tip of the Birgu peninsula was strengthened as were the fortifications at Birgu where the order had its headquarters. Fort St Michael was built at the neck of the Senglea Peninsula, and on the sea point of Mount Sciberras construction was started on the star-shaped Fort St Elmo.[181]

The Grand Master of the Order, Jean Parisot de la Valette had made it his business to improve the island’s defenses and developed it into a powerful fortress. La Valette had fought at Rhodes and learned much from his many experiences in battle. He made good use of natural and artificial obstacles, repaired old watchtowers, enlarged ramparts, strengthened walls, and deepened ditches. La Valette realized that he could count on little in the way of aid, and set up his command to be as self-sufficient as possible. He was left to defend the island with a force of about 600 Knights and some 8500 soldiers including 3000 Maltese regulars who fought well.

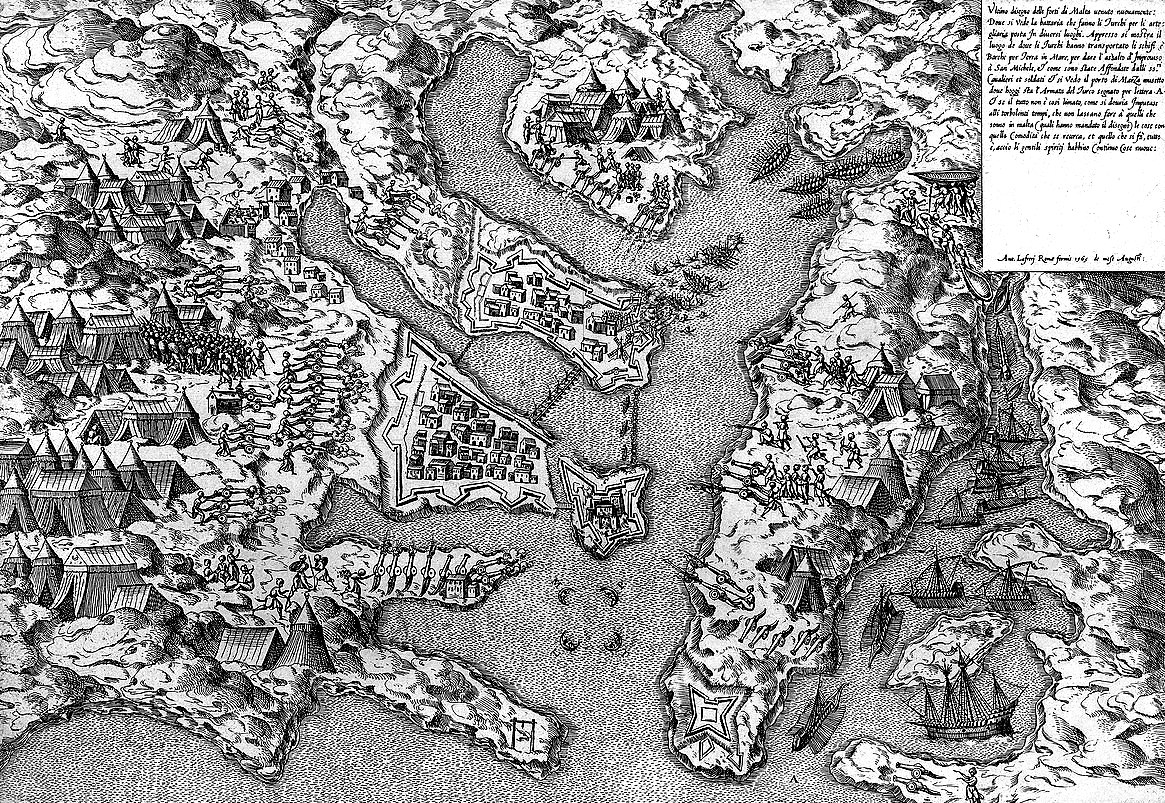

Detailed Map of the Siege of Malta, a fresco by Egnazio Dante.

Preparing for the forthcoming siege, foodstuffs were stored away, weapons and firebombs were made and training was stepped up. La Valette prepared his plans and eliminated any weaknesses in the island’s defenses, for he knew full well that if Malta fell, the Order was finished. The steel clad Knights carried a heavy two-handed sword and had an assortment of weapons that included pikes, spears, arquebuses (an early model matchlock hand-held firearm), muskets and a variety of fireworks that included a combustible pot used like a grenade/flame-thrower. They used a refined form of Greek fire in a device called a trump, as well as specially prepared flaming hoops. These were particularly deadly, for they could encircle three or four Janissaries at a time and set alight their voluminous robes with unquenchable flame. In the matter of cannon however, the Turks had the advantage in numbers and weight.[182]

The Turks assembled a huge armada of 181 vessels to transport the invasion army to Malta, and set off with troops well furnished with personal weapons, equipment and rations, and had been well briefed that they would find neither houses for shelter, nor earth, nor wood and would not be living off the land. Both sides appear to have had good intelligence on the ground and the coming battle.

Lookouts spotted the Turkish fleet and fired cannon shots to warn the Knights. Over 30,000 Turkish troops landed, including 6,300 Janissaries and 6,000 Spahis (who were expert bowmen), far too many for La Valette to counter attack with his force of 9000. He instead withdrew to the strongpoints and fortifications he had already prepared.

The command of the Turkish force was split, with the army commanded by Mustapha Pasha who had also fought at Rhodes, and the fleet commanded by Piali. They had a vast quantity of stores with them in a transport fleet, including food, powder, shot, tents and clothing, as well as a number of horses to drag the heavy guns. It was a well-executed logistic undertaking.[183]

The initial Turkish attacks against the strongpoints were thrown back with significant losses to the Turks. Two fortified islands at the entrance to the harbor, St Elmo and St Angelo, were now targeted for assault. 50 Knights and 500 men garrisoned St Angelo. St Elmo was a well-defended old-fashioned star fortress on a rocky headland, defended by some 53 knights and 800 soldiers. On 31 May the Turks had 24 guns aligned against the front of St Elmo, and shelled the fort for days, but suffered heavy losses while pressing home the attack. Pounded by a hail of stone, marble and iron cannon-balls, the walls of St Elmo began to crack. In desperation the garrison sortied out and inflicted huge casualties on the panic stricken Turks. The Janissaries of Mustapha Pasha checked their retreat and the attack was renewed.

More Turkish ships arrived with another 1500 soldiers under the command of Dragut, the Governor of Tripoli. He redirected the efforts against the walls of St Elmo and effected breaches in several places. Exhausted as the defenders were, however, they still managed to beat off a scaling party, driving the Turks back with musket shots, stone blocks, boiling pitch and Greek fire. Wave after wave of Janissaries were cut down by the defenders. After losing nearly 2000 men, Mustapha called off the first attack. A second attack was put in at night, leaving another 1500 Turks dead or dying just outside the fort, for the loss of only 60 defenders. Six days later the Turks tried again, after a prolonged bombardment. Fighting back with firebombs and incendiaries, the invaders were again thrown back with tremendous casualties, to the loss of 10 Knights and 73 soldiers for the defenders.

Dragut was killed on 18 June, but the fortress of St Elmo finally fell on 23 June. Although the crescent flag of Islam finally flew over the fort, the victory gave them little joy. For every one of the 1500 Christian casualties, the Turks lost seven. The only survivors of St Elmo were nine Knights taken as hostages and a handful of Maltese who swam across the harbor to safety. All the others were decapitated and their heads fixed on stakes turned towards the other fort of St Angelo. In retaliation, La Valette gave orders that all the Turkish prisoners were to lose their heads, which were then fired like cannon-balls into the captured St Elmo fort.

Mustapha’s next move was against the two peninsulas on Senglea and Birgu on the main island. The Grand Master strengthened the defenses of both and ensured that adequate food stocks were in place. A bridge of boats connecting the two peninsulas was maintained so that men on one could go to the help of the other if attacked. The Turks managed to bring some 80 ships overland and into the Grand Harbor, clearly indicating that the next attack would be against St Michael’s fort and the Senglea peninsula. The chain and the guns of St Angelo would keep these ships from the Birgu peninsula. This was confirmed when a Greek officer serving in the Turkish army defected and disclosed Mustapha’s intentions.

As a result, when Senglea was attacked simultaneously by land and sea on 15 July, the Knights and their Maltese supporters were able to counter both threats. Even the local inhabitants joined in, women and children flinging down missiles and pouring boiling water on the unlucky Turks who tried to scale the walls. This attack cost the Turkish forces another 3000 casualties. The Hospitallers had lost 250, but these included the commander of the spur.

The Turkish commander then attacked both garrisons simultaneously, so that one could not reinforce the other. Mustapha led the attack personally, but it again failed. In spite of the fact that he had lost over 10,000 men since his landing in Malta, he chose to continue the siege. La Valette confirmed that he had adequate supplies, but was unlikely to receive outside help. If the Turks were victorious however, he concluded that no one would be spared. He only course therefore, was to continue to resist.

The Turks now resorted to mining. They also brought up a special siege engine; a tall tower complete with drawbridge for use against the wall after their mines had exploded. They again preceded the grand assault with a massive bombardment. 26 guns rained shot on the Castile bastion, while St Angelo was under fire from two batteries, and those on Coradin took care of Senglea. The damage was considerable, but not nearly as great as Mustapha had hoped. Although they managed to blast a hole in the wall of one of the bastions, the attackers who pushed through the gap were beaten back on 02 August, in one of the bloodiest encounters of the siege. Although the offensive was resumed under cover of darkness, the Turks were forced to withdraw at dawn. The battle dragged on, and on 18 Aug Mustapha had a large mine detonated under the main wall of the Castile bastion, but owing to the personal intervention of the Grand Master this attack also failed. Mustapha then ordered a large siege tower laden with troops brought forward to the wall, but La Valette was ready for it. His workmen punched a hole in the wall opposite the base of the machine, trained a cannon on the lower part of the structure and shattered its foundations with chain shot. The whole affair collapsed and the men inside were thrown to the ground.

It was not a good day for the Turks. They prepared a second invention, a kind of homemade shrapnel bomb. It came in the form of a large cylinder filled with shot, stones and nails timed to explode when it had been maneuvered and dropped over the wall, but it had a faulty fuse and failed to explode. Profiting by the delay, the Knights hauled it to the top of the wall and dropped it in the ditch among the attacking party. It blew up almost at once with horrendous effect, scattering the Turks as they ran for their lives.

The Turks had fired some 70,000 cannonballs in the siege and they were running short of powder. They needed a success, and the attacks continued to the end of August, but without noticeable change in either position except the wearing down of the forces of both sides.

Lifting of the Siege of Malta, painting by Charles Philippe Lariviere.

Although Mustapha maintained his efforts, a new problem confronted him. The Viceroy of Sicily, an ally of the Knights, sailed to Malta on 25 August with a relief force of nearly 10,000 men. Misinformed by a slave who had been deliberately permitted to escape by la Valette, Mustapha was led to believe that the Viceroy had brought 16,000 troops. This led Mustapha to make up his mind to evacuate Malta. He discovered that he had been misled during the embarkation and immediately halted the evacuation, landed about 9000 men and unhesitatingly gave battle. La Valette’s Knights, led by Ascanio de la Corna, made a spectacular charge and utterly routed the Turks. Mustapha was only saved from capture by a devoted group of Janissaries. A Turkish rearguard of arquebusiers was formed and these men did their work well until forced to retire when confronted by the full weight of de la Corna’s force. The Turks lost another 1,000 men, and on the evening of 8 September 1565 the Turkish fleet finally sailed from Malta.

(R Muscat Photo)

Mdina, Malta, aerial view.

The cost to the island had been severe, as out of the original 9000 only 600 were strong enough to bear arms. Of the Knights, close to 250 had died, along with 7,000 Maltese, Spaniards and other nationals. The Turkish forces had suffered over 30,000 casualties, and it is thought that no more than 10,000 of the force of nearly 40,000 reached Constantinople, and many of those were wounded or sick. This unsuccessful siege marked the end of the Turkish dreams of conquest and domination, and as a result, the whole of Europe had good reason to be grateful to the island that refused to surrender.[184]

Tenochtitlan, 1521

The ideas of the old world were not long in coming to the new one. Conquest and the Spanish Inquisition soon followed.[185] Between May and August 1521, the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés and his forces attacked Tenochtitlan, the capital of Mexico’s Aztec empire in an assault that left more than 100,000 dead.[186] The Aztecs fought hard; in one gruesome, defiant act, they first humiliated their Spanish prisoners by making them dance and wear feathers, then ripped out their hearts and threw the bodies down a temple pyramid’s steps. After 80 days of onslaught, the Aztec king, with his people ill and starving, surrendered to Cortés, and the Aztec empire vanished.[187]

(Infrogmation Photo)

The Last Days of Tenochtitlan, Conquest of Mexico by Cortez”, a 19th-century painting by William de Leftwich Dodge.

Mexico fell to Cortés on 13 August 1521. The Aztec Empire then became New Spain under the authority of Cortes, who was named Captain General. In effect Cortés, with the aid of 600 soldiers, sixteen horses, ten cannons and thirteen arquebuses conquered a country that in 1519 had 20 million subjects under the reign of Motecuhzoma II. The valley of Mexico, which alone may have had as many as five million inhabitants, was at that time the greatest urban concentration in the world.

Siege of Nagshino, 1575

The Battle of Nagashino (Nagashino no Tatakai) took place in 1575 near Nagashino Castle on the plain of Shitarabara in the Mikawa Province of Japan. Takeda Katsuyori attacked the castle when Okudaira Sadamasa rejoined the Tokugawa, and when his original plot with Oga Yashiro for taking Okazaki Castle, the capital of Mikawa, was discovered.

Takeda Katsuyori attacked the castle on 16 June, using Takeda gold miners to tunnel under the walls, rafts to ferry samurai across the rivers, and siege towers. On 22 June the siege became a blockade, complete with palisades and cables strewn across the river. The defenders then sent Torii Suneemon to get help. He reached Okazaki, where Ieyasu and Nobunaga promised help. Conveying that message back to the castle, Torii was captured and hung on a cross before the castle walls. However, he was still able to shout out that relief was on the way before he was killed.

(Moccy Photo)

Site of Nagashino Castle, Shinshiro, Aichi Japan.

Both Tokugawa Ieyasu and Oda Nobunaga sent troops to assist Sadamasa and break the siege, and their combined forces defeated Katsuyori. Nobunaga’s skillful use of firearms to defeat Takeda’s cavalry tactics is often cited as a turning point in Japanese warfare; many cite it as the first “modern” Japanese battle. In fact, the cavalry charge had been introduced only a generation earlier by Katsuyori’s father, Takeda Shingen. Furthermore, firearms had already been used in other battles. Nobunaga’s innovation was the wooden stockades and rotating volleys of fire, which led to a decisive victory at Nagashino.

Nobunaga and Ieyasu brought a total of 38,000 men to relieve the siege on the castle by Katsuyori. Of Takeda’s original 15,000 besiegers, only 12,000 faced the Oda–Tokugawa army in this battle. The remaining 3000 continued the siege to prevent the garrison in the castle from sallying forth and joining the battle. Oda and Tokugawa positioned their men across the plain from the castle, behind the Rengogawa, a small stream whose steep banks would slow down the cavalry charges for which the Takeda clan was known.

Seeking to protect his arquebusiers, which he would later become famous for, Nobunaga built a number of wooden palisades in a zig-zag pattern, setting up his gunners to attack the Takeda cavalry in volleys. The stockades served to blunt the force of charging cavalry.

Of Oda’s forces, an estimated 10,000 Ashigaru arquebusiers, 3,000 of the best shots were placed in three ranks under the command of Sassa Narimasa, Maeda Toshiie and Honda Tadakatsu. Okubo Tadayo was stationed outside the palisade, as was Sakuma Nobumori, who feigned a retreat. Shibata Katsuie and Toyotomi Hideyoshi protected the left flank. Takeda Katsuyori arranged his forces in five groups of 3,000, with Baba Nobuharu on his right, Naito Kiyonaga in the center, Yamagata Masakage on the left, Katsuyori in reserve and the final group continuing the siege. A night attack on the eve of the battle by Sakai Tadatsugu killed Takeda Nobuzane, a younger brother of Shingen.

The Takeda army emerged from the forest and found themselves 200–400 meters from the Oda–Tokugawa stockades. The short distance, the great power of the Takeda cavalry charge and the heavy rain, which Katsuyori assumed would render the matchlock guns useless, encouraged Takeda to order the charge. His cavalry was feared by both the Oda and Tokugawa forces, who had suffered a defeat at the Mikatagahara.

The horses slowed to cross the stream and were fired upon as they crested the stream bed within 50 meters of the enemy. This was considered the optimum distance to penetrate the armor of the cavalry. In typical military strategy, the success of a cavalry charge depends on the infantry breaking ranks so that the cavalry can mow them down. If the infantry does not break, however, cavalry charges will often fail, with even trained warhorses refusing to advance into the solid ranks of opponents.

Between the continuous fire of the arquebusiers’ volleys and the rigid control of the horo-shu, the Oda forces stood their ground and were able to repel every charge. Ashigaru spearmen stabbed through or over the stockades at horses that made it past the initial volleys and samurai, with swords and shorter spears, engaged in single combat with Takeda warriors. Strong defenses on the ends of the lines prevented Takeda forces from flanking the stockades. By mid-day the Takeda broke and fled, and the Oda forces vigorously pursued the routed army. Takeda suffered a loss of 10,000 men, two-thirds of his original besieging force. Several of the 24 Generals of Takeda Shingen were killed in this battle. (Turnbull, Stephen. Battles of the Samurai. London: Arms and Armour Press, 1987)

Science of Fortification

The Spanish built one of the earliest fortified settlements in North America along the Florida coast at St Augustine in 1565. It included eight artillery bastions and a star citadel. Quebec City, founded in 1608 on the St Lawrence was sited on a defendable position and equipped with artillery emplacements covering both the land and river approaches from its walled citadel.[188]

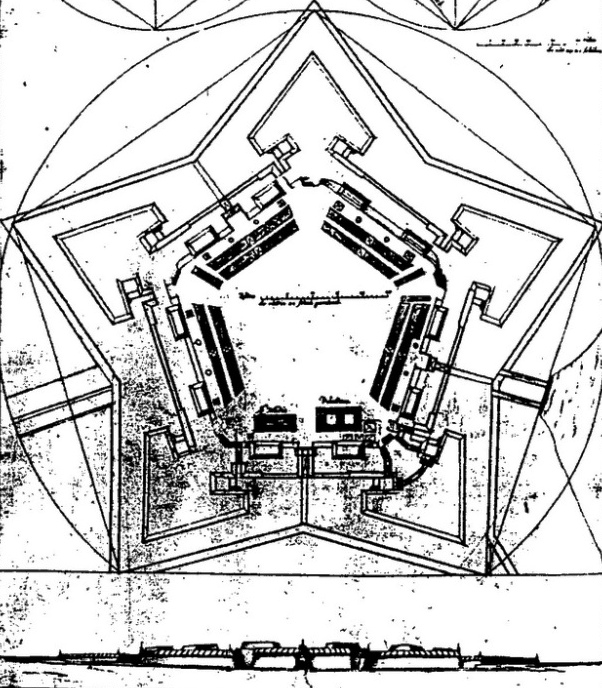

Star citadel of Antwerp, Belgium, diagram.

The citadel of Antwerp was built in 1567 in the wake of religious wars in the Netherlands. It was commissioned by the Duke of Alva sent by Philip II of Spain to quell any resistance in Antwerp. It served both as a defensive structure as well as a base of operations for Spanish, Austrian, French, Dutch and Belgian forces. The citadel features a five pointed star with bastions, and was constructed close to the Scheldt river. In 1572 the citadel was completed and a garrison moved in. It became notorious for the Spanish Fury in 1576 where the city was plundered and many citizens lost their lives. In a response to the atrocities committed during the Spanish Fury notables of Antwerp ordered the wall facing the city to be demolished in 1577. When hostilities resumed, it became a citadel once again. The five bastions were named Toledo, Pacietto, Alva, Duc and Hernando. The citadel featured many buildings including powder magazines and a chapel, and has been updated several times. The French refitted the citadel when Antwerp became the Arsenal for a Maritime assault force that was planned for an invasion force for England. The lunets named of Kiel and Saint Laurels were added at that time. During the Belgian occupation of the fort an extra battery on the terreplein was also added. 1832 it became the theater of Dutch resistance during the Belgian war of independence as a French army besieged this fortress under the command of Marshal Gérard. In 1870 King Leopold II of Belgium ordered the sale and leveling of the citadel, and thus, no visible traces exist.

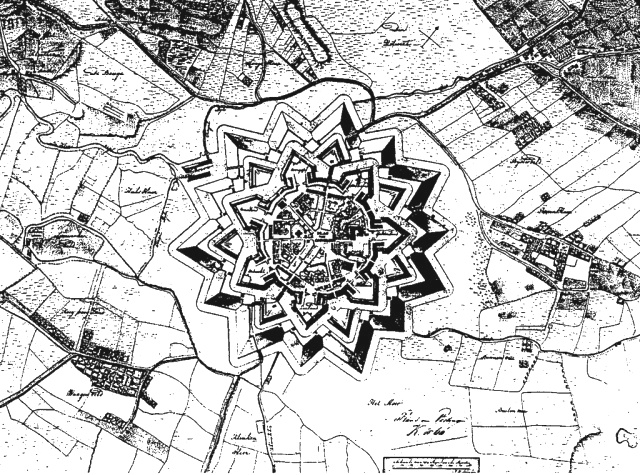

Coevorden citadel diagram, Netherlands.

(Rijkmuseum Photo)

Painting of the re-capture of Coevorden by Dutch troops commanded by Carl von Rabenhauptin December 1672, as part of the Franco-Dutch War.

The idea of using bastions in fort design was expanded and soon multi-pointed star forts were being developed towards the end of the 16th century. Maurice of Nassau for example, rebuilt Coevorden, Holland by adding bastions resulting in the formation of a 14-point star.

The city of Coevorden was captured from the Spanish in 1592 by a Dutch and English force under the command of Maurice, Prince of Orange. The following year it was besieged by a Spanish force but the city held out until its relief in May 1594. Coevorden was then reconstructed in the early seventeenth century to an ideal city design, similar to Palmanova. The streets were laid out in a radial pattern within polygonal fortifications and extensive outer earthworks.

The city of Coevorden may have indirectly given its name to the city of Vancouver, which is named after the 18th-century British explorer George Vancouver. The explorer’s ancestors (and family name) may have originally come to England “from Coevorden” (van Coevorden > Vancoevorden > Vancouver).

(itinari.com/palmanova-the-star-shaped-city-hkts)

Palmanova, Italy, was planned as an 18-point star. Palmanova was founded on October 1593 by the superintendent of the Venetian Republic. The city’s founding date commemorated the victory of the Christian forces (supplied primarily by the Italian states and the Spanish kingdom) over the Ottoman Turks in the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, during the War of Cyprus. Also honored on 7 October was Saint Justina, chosen as the city’s patron saint. Using all the latest military innovations of the 16th century, this small town was a fortress in the shape of a nine-pointed star, designed by Vincenzo Scamozzi. Between the points of the star, ramparts protruded so that the points could defend each other. A moat surrounded the town, and three large, guarded gates allowed entry. The construction of the first circle, with a total circumference of 7 kilometres (4 mi), took 30 years. Marcantonio Barbaro headed a group of Venetian noblemen in charge of building the town, Marcantonio Martinego was in charge of construction, and Giulio Savorgnan acted as an adviser. The second phase of construction took place between 1658 and 1690, and the outer line of fortifications was completed between 1806 and 1813 under the Napoleonic domination. The final fortress consists of: nine ravelins, nine bastions, nine lunettes, and eighteen cavaliers.In 1815 the city came under Austrian rule until 1866, when it was annexed to Italy together with Veneto and the western Friuli. Until 1918, it was the one of easternmost towns along the Italian-Austro Hungarian border and during the First World War the city worked as a military zone hosting even a hospital for the royal army. In 1960 Palmanova was declared a national monument. (John Rigby Hale, “Renaissance war studies”, (London Hambledon Press, 1983), pg. 18.

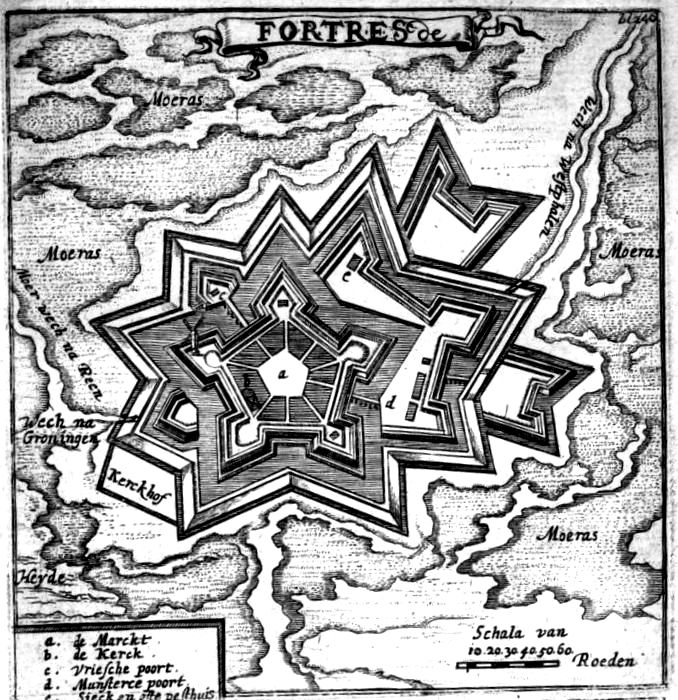

Fort Bourtange, Netherlands, diagram.

(onebigphoto.com)

Fort Bourtange, Netherlands, aerial view.

Fort Bourtange is a star fort located in the village of Bourtange, Groningen, Netherlands. Built in 1593 under the orders of William the I of Orange, its original purpose was to control the only road between Germany and the city of Groningen, controlled by the Spaniards during the time of the Eighty Years’ War. After experiencing its final battle in 1672, the Fort continued to serve in the defensive network on the German border until it was finally given up in 1851 and converted into a village. Fort Bourtange currently serves as a historical museum.

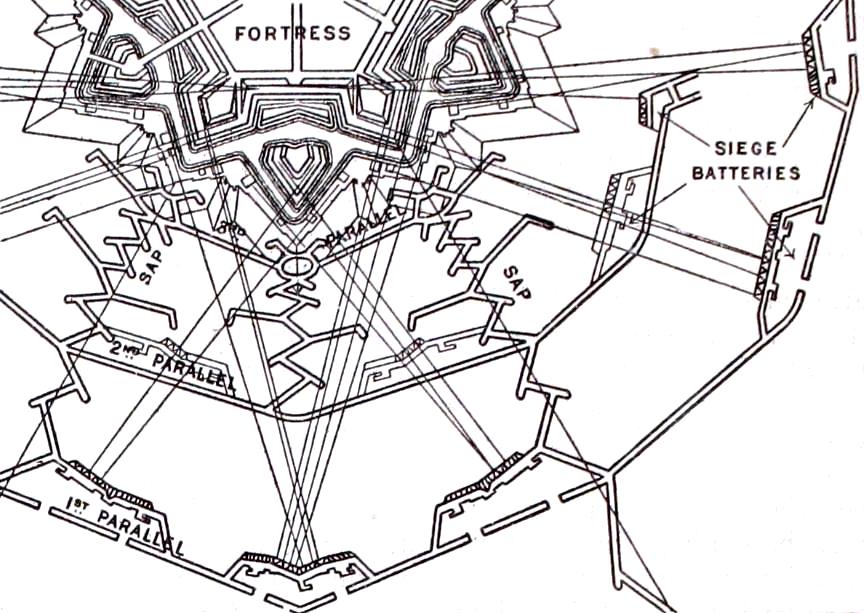

Vauban’s system of attack.

European engineers such as Marchi and Busca in Italy, and de Ville and Pagan in France, helped to develop the science of fortification. The two most prolific designers in Northern Europe were Sebastien le Prestre de Vauban (1633-1707), and Menno de Coehoorn (1641-1704). Vauban devised a method of conducting sieges that involved a geometric advancement of trenchworks and approaches that moved from parallel to parallel against enemy fortifications that was highly successful.[190] He used these parallels in the attack on Maastricht in 1673, capturing the “impregnable” fortress after an assault of only 13 days.[191] Vauban applied the use of common sense rather than untried theory to achieve these successes.[192] Be that as it may, his ideas were to be put into use for the next 200 years.[193]

Coehoorn is renowned not only for the small, mobile mortar that bears his name, but for his skill in strengthening fortifications at such places as Coevorden, Bergen-op-Zoom and Namur, and for his treatise on fortifications. He designed his systems with certain specific principles in mind: to provide powerful flank defense; to deprive an attacker of the means of making lodgments; to give ample facilities for sorties; and to avoid unnecessary expense. Whenever possible, he relied on water as a means of defense. While generally keeping to the usual bastioned polygon of his era, he adopted earthwork counterguards which he made too narrow for an attacker to use as gun platforms. He developed the fausse braye into a narrow embankment alongside the ditch protecting it by means of a counterscarp gallery (a loopholed passage behind the counterscarp wall), a wide promenade which was virtually the same as that of the water in the ditch and which was carefully flanked by artillery casemates and musketry galleries. Its level was deliberate; if an attacker attempted to cut a trench across, they would immediately strike water. Similarly the covered way was close to the water level so as to deter any attempts to sap or trench across it.[194]

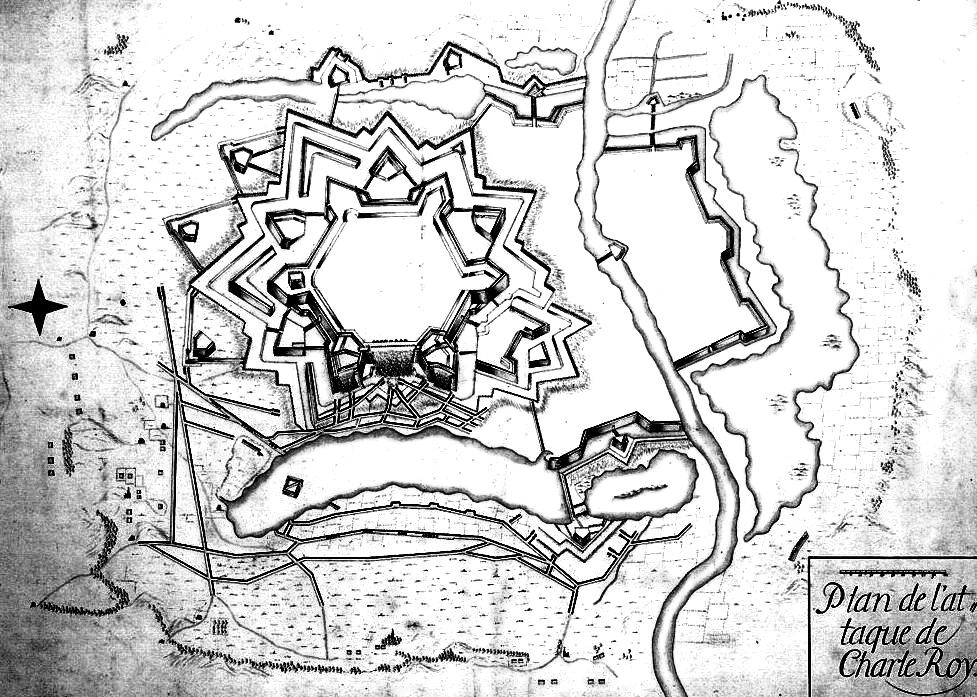

Fortress Charle Roy, France, diagram of the plan of attack, 1693.

(B.R. Davies)

Plan of Geneva, Switzerland and environs, showing the massive fortifications in 1841, less than ten years before the start of their demolition in 1850.

In 1777, the Marquis de Montalembert designed a fortress known as a caponiere. It was a heavily walled structure three stories high and at a right angle to the main wall. Each story was a great gun platform, effectively placing large numbers of guns and therefore concentrated firepower on any attacking force. These forts were primarily sited in the defense of harbors and have been built all over Europe at sites from Sebastopol in the Crimea, to Toulon in southern France, to Portsmouth, England and then across the Atlantic to Fort Sumter in South Carolina, and Fort Point in San Francisco Bay, California.[195] Eventually, fortified places could not be properly defended without large field armies supporting them. Even then, once the field army was defeated, it was almost inevitable that the fortresses would fall. Often armies would just bypass them altogether.[196]

Explosive technology also progressed. Although rockets may have been used as early as the 13th century in Asia, the British army noted what seems to have been the first modern use of a war-rocket by the Sultan Tipu at the siege of Seringapatam in 1799. Rockets were used in 1806 at the siege of Boulogne to set the town on fire, and at Walcheren and Copenhagen in 1807, at the battles of Leipzig and Waterloo and at New Orleans in 1815.[197] Hitler and his V2 rockets launched during the Second World War against allied cities in 1944, was followed a generation later by Iraq’s Saddam Hussein firing on the cities of Iran and Israel in 1991.

Good intelligence often had a decisive role to play in the outcome of a siege. Because every major siege of the 17th and 18th centuries involved major problems of logistics operations, preparations were very hard to conceal. Vauban stated that the foremost fault committed in siegecraft came from insufficient attention to basic security and secrecy. He also stated that no fortress, however well defended, could hold out indefinitely.[198]

English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians (“Roundheads”) and Royalists (“Caviliers”) over, principally, the manner of England’s government. The first war (1642–1646) and second war (1648–1649) pitted the supporters of King Charles I against the supporters of the Long Parliament, while the third war (1649–1651) saw fighting between supporters of King Charles II and supporters of the Rump Parliament. The war ended with the Parliamentarian victory at the Battle of Worcester on 3 Sep 1651.

(Tate Collection)

Oliver Cromwell at Dunbar, painting by Andrew Carrick Gow 1881.

The overall outcome of the war was threefold: the trial and execution of Charles I (1649); the exile of his son, Charles II (1651); and the replacement of the English monarchy with, at first, the Commonwealth of England (1649–1653) and then the Protectorate under the personal rule of Oliver Cromwell (1653–1658) and subsequently his son Richard (1658–1659). The monopoly of the Church of England on Christian worship in England ended with the victors consolidating the established Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. Constitutionally, the wars established the precedent that an English monarch cannot govern without Parliament’s consent, although the idea of Parliament as the ruling power of England was only legally established as part of the Glorious Revolution in 1688.

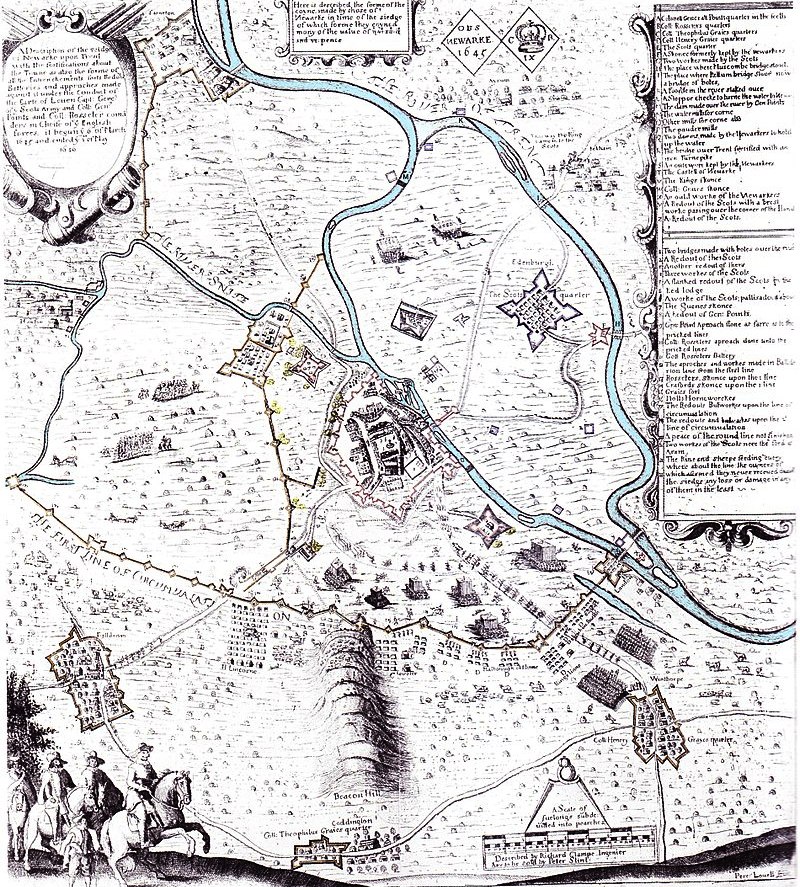

The English Civil War of the 1640s saw the development of surprisingly defendable town walls, in spite of the already extensive use of cannon to degrade stone fortifications. Complicated lines of circumvallation and earth work bulwarks and bastions laid out in scientifically calculated patterns by Dutch designers gave the defender a fighting chance against a determined attacker. Bernard de Gomme of the Netherlands was one of the most celebrated engineers of his time for his designs of effective fortification systems. Gomme set up a new and very strong system at Newark, the strongest royal city after Oxford which was defended by the “royalists,” and attacked by the “parliamentarians.”

This city was sited on the Trent River and had been regarded as a strategic location since ancient times. There were Roman defense works in two places, which were later superceded by “New Work” in 900, (from which the town received its name) to protect the site against the Danes. Early in the 12th century, the town and manor came under the control of the bishops of Lincoln, who built a finely ornamented stone castle on a commanding position overlooking the river, a bridge and the road leading to it. Throughout the Middle Ages the fortress at Newark was strengthened and added to, and even in the 17th century is was still one of the most powerful river castles in England.

At the end of 1642, King Charles generals decided to fortify and to heavily garrison Newark. It became in fact, the center of a large fortified area and was used as a rallying point for the King’s army, as well as a supply center. Newark had to be held because it overlooked the Great North Road which bridged the Trent River and bisected the main road linking Lincoln to Nottingham and Leicester. It protected the lines of communication between the King’s headquarters in Oxford and his strongholds in Yorkshire and Newcastle, where his supplies of arms that were brought in by sea from the Netherlands were usually landed. By holding Newark, it was also possible for the King make effective use of his “army of the north” under the command of the Earl of Newcastle to launch a thrust into the territory of the Eastern Association. This was the main source of parliamentary military power.

Siege of Newark, 1645-1646

Clampe’s map of the siege of Newark (6 March 1645 – 8 May 1646) showing in green a sap that allows Roundhead siege artillery to be placed closer to the fortifications of Newark than the circumvallation. Notice that the lines of advance of the zigzag are at such an angle and position that the defenders were unable to bring enfilade fire to bear.

The castle at Newark and its defensive system was linked to other royalist castles in the area, including Belvoir, all of which were heavily garrisoned. From this defensive zone a large area was scoured for supplies and manpower. It also served as a base from which to mount cavalry raids into the neighboring parliamentary territory.

The Parliamentarians made three major attempts to take the city. Major General Thomas Ballard launched an attack in February 1643 with 6,000 men and ten guns, most of which were small six-pounders. He fired 80 shots into the town. But a fierce counter-attack cost him three of his guns and 60 prisoners and broke the siege.

The second parliamentary attack came which came a year later in February 1644, was even less successful. Sir John Meldrum surrounded the defensive zone with 2,000 horsemen, 5,000 foot-soldiers, eleven cannon and two mortars. The cannon included one famous monster which had been named “Sweet Lips” (after a notorious Hull whore of that time). Sweet Lips was described as a “great basilisk” from Hull, four yards long and probably cast in the 16th century. The gun fired a 30-lb ball to a distance of 400 yards at point blank range and possibly as far as 2,400 yards at ten degrees of elevation.

Meldrum built a pontoon bridge of boats over the Trent River to help his forces conduct an investment of the royalist lines. In the process, however, he was surprised and surrounded by Prince Rupert and was forced to surrender in what could be assessed as the single worst parliamentary disaster of the war. He was allowed to march wary, but lost all of his guns, his small arms and his ammunition train.

The third siege began in November 1645,when the main Scots army joined General Poyntz and his English force. This was the first time the Newark defenders commanded by Lord John Belasyse faced determined professional soldiers. The Scots constructed a great battering-fort they named “Edinburgh”, a siege device which was the 17th century equivalent of a malvoisin. General Poyntz also had a giant bastion brought into play which was named “Colonel Grey’s Sconce.” The Scots set up two boat bridges and brought up an armed pinnace which also mounted two guns manned by 40 musketeers. These were used to penetrate the Trent River defenses to within half a mile of the castle itself. General Poyntz also dammed the Smite River and the arm of the Trent which ran directly under the castle, putting the town mills out of action.

By the end of March 1646, some 7,000 Scots and 9,000 English had dug themselves into the town roughly to within the range of cannon shot. By April, General Poyntz had diverted both rivers away from Newark and had dug saps up to the main outwork of Newark, which had been named the “Queen’s Sconce.” He had also built a battery within musket shot of one of the town gates. The Scots by this time had the castle itself within range of their guns. The defenders surrendered in May.

Lord John Belasyse had done his best to provision the town the previous winter, but the defenders were now reduced to eating their horses. Plague broke out, and because they had been deprived of water for cleaning and washing, everyone in the town suffered.[199] Even so, Belasyse had to be ordered to surrender. He didn’t want to, as his men were still in good heart, and in the end, he marched out with a company of about 1,500. General Poyntz was awarded a £200 sword by the Commons, and lands worth £300 a year. Newark was the last major action of the First Civil War; Oxford would surrender in the following month.

The royalists had demonstrated in two out of three sieges, that if a fortification was properly garrisoned and provisioned, they could withstand a considerable amount of punishment. Even primitive earthworks could keep a besieger’s cannon from firing point-blank at the walls and towers, and could enable them to hold out long enough for a relieving force to arrive. The castle at Donningham, for example, was fortified in September 1643 and defended by Colonel John Boys, who built a complete set of star-shaped earthworks around it. In July 1644,the Earl of Essex sent General Middleton to take it with 3,000 dragoons and light cavalry. Middleton had no “big” guns, and lost 300 men in a hopeless attempt to attack the fortifications with scaling ladders. In September, Colonel Horton took over with a siege train. He shot at it for 12 days and “beat down three towers and a part of a wall,” but could not compel the defenders to surrender. In October, the Earl of Manchester wanted to try to take it by storm again, but apparently his men declined to carry it out. They had fired over 1,000 rounds of “great shot” in 19 days against the defender’s walls without causing any further damage to the garrison except wrecking some more of its defenses.

Eventually, Donningham was besieged again at the end of 1645 when Cromwell ordered Colonel Dalbier to take it. Colonel Boys delayed the end by building a large satellite bastion on the castle hill, from which he launched a number of sorties. Unfortunately, he couldn’t match a giant mortar which Colonel Dalbier had acquired. This mortar fired 17 large rounds against the staircase tower of the fortifications gatehouse, pounding a large hole in it. After a parley in March 1646, Colonel Boys surrendered with 200 men, 20 barrels of gunpowder and six guns. His men marched out with colours flying, muskets loaded and every man packing as much ammunition as he could carry, under the honorable terms and conditions agreed to at the parley.[200]

Siege of Groningen. Engraving by Bernhard von Galen, 1672.