Ley Lines, found in the UK and others stretching out from Alaise, France

Leys may be defined as lines of energy running over-ground in straight lines, often reflected in the paths of ancient trackways and subsequently Roman roads, and in alignments of prehistoric and historic sacred sites in the landscape. In modern times they were first described by Alfred Watkins in his 1925 book ‘The Old Straight Track’.

In the early 1920’s, Alfred Watkins identified ley lines found in Great Britain as being associated with ancient traders’ routes only. He could not find a reasonable explanation, however, for the fact that many of them “traveled up prohibitively steep hillsides”. These straight-line networks can be found throughout the world, and some of the ley lines stretch for hundreds of miles.

Alfred Watkins first became aware of the prehistoric alignment of ancient sites covering the English landscape. He concluded that a feature of the old alignments was that certain names appeared with a high frequency along their routes. Names with Red, White and Black are common; so are Cold or Cole, Dod, Merry and Ley. (The last as we know, he used to name the lines, although it has been noted that ‘ley’ is Saxony for ‘fire’). He suggested that ancient travellers navigated using a combination of natural and man-made markers. Certain lines were known by those that most frequented them so that ‘White‘ names were used by the salt traders; ‘Red‘ lines were used by potters, ‘Black‘ was linked to Iron, ‘Knap‘ with flint chippings, and ‘Tin‘ with flint flakes. He suggested that place names including the word ‘Tot’, ‘Dod” or ‘Toot’ would have been acceptable sighting points so that the ‘Dodman‘, a country name for the snail, was a surveyor, the man who ‘planned’ the leys with two measuring sticks similar to a snail’s horns (or the ‘Longman of Willington’) (It is noted that the Germans have similar names such as ‘Dood’ or “Dud’, which mean ‘Dead’). Watkins maintained that leys ran between initial ‘sighting posts’. Many of the ‘mark stones’, and ‘ancient tracks’ he refers to have since disappeared, a situation which is considerably unhelpful to serious research. Similarly to Guichard (above), Watkins believed that the lines were associated with former ‘Trade routes’ for important commodities such as water and salt. He found confirmation in this through ‘name-associated’ leys. Even today the Bedouins of North Africa use the line system marked out by standing stones and cairns to help them traverse the deserts. A letter to the Observer (5 Jan 1930), notes similarities with Watkins theories and the local natives of Ceylon, who had to travel long distances to the salt pans. The tracks were always straight through the forest, were sighted on some distant hill, (called ‘salt-hill’), and that the way was marked at intervals by large stones (called ‘salt-stones’), similar to those in Britain. On the other hand, should the leys be ancient tracks then it should be possible to see one point from another. Also it is noted that there are many ancient ‘tracks’ across Britain, such as the Ridgeway, and none of them are dead straight.

Both the French and English Ley’s have a prehistoric precedence, with roots in the Neolithic period. (http://www.ancient-wisdom.com/xavierguichard.htm)

The Long Man of Wilmington Ley, Sussex, United Kingdom.

(Steve Slater Photo)

These straight (at least over perhaps 60 miles with slight changes of path over longer distances, according to variations in map projection) spirit paths are found equally in China as elsewhere in the world, and frequently define the processional routes to major palaces, temples and cathedrals, as well as sites of temporal power, the world over.

Some of the largest Leys describe great circles through a series of important sites around the planet. Others have been dowsed as starting with an energy stream vertically down from the sky, then travelling across the country for perhaps a hundred miles before passing on down into the earth. They can vary from five yards to several hundred yards in width, with only the larger ones being particularly associated with ceremonial sites along their course. (https://landandspirit.net/earth-energies/leylines/)

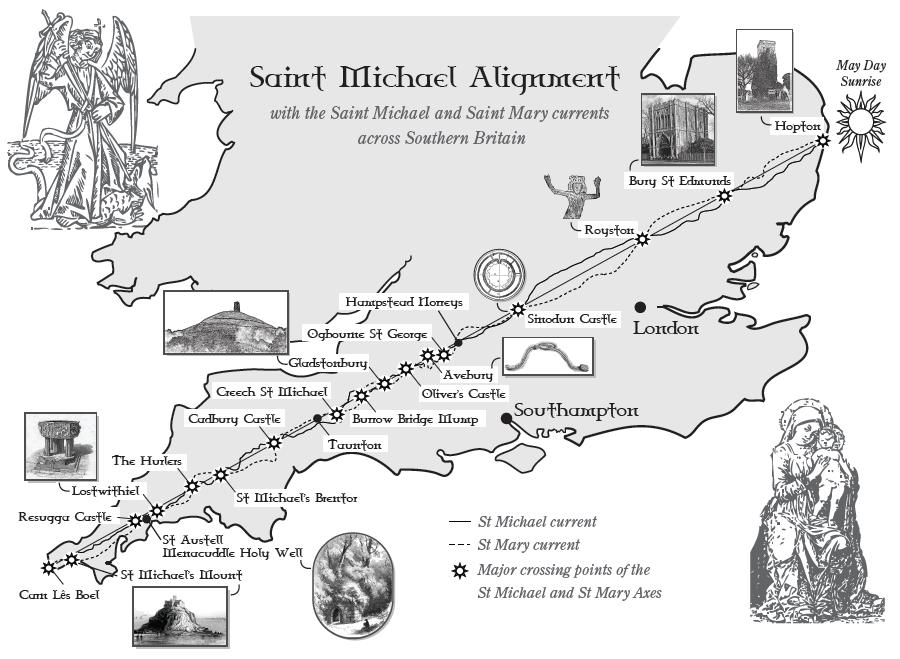

The St. Michaels Ley Line, aka the Apollo-Athena Line (Mappa Linea Sacra di San Michele).

The Apollo-Athena Line runs across Europe oriented 60°11′ west of North. It passes through Skelig Michael in Ireland, St. Michael’s Mount in the UK, Mont St. Michel, Mayenne, Le Mans, Tours, Blois, Issoudun, Bourges, Sancoins, Nevers, Moulins, Digois, Charolies, St. Vincent des Pres, Cluny, Macon, Perouges, Lyons, Vienne, St. Beron, Bozel, Sacra di San Michele (Turin) in France, San Michele (Castiglione di Garfagnana), Perugia, Monte Sant Angelo (Gargano) in Italy, Delphi and Athens in Greece, Mount Carmel and Armageddon in Israel. (Miller & Russell)

The St. Michael’s Leyline follows the path of the Sun on the 8th May (The spring festival of St. Michael).

The St. Michael’s ley has been shown to be inter-related with several other prominent British megaliths through geometry, astronomy and an apparent knowledge of longitude/latitude, not least of all to Stonehenge. Stonehenge, whilst not being a part of the St. Michael ley, is connected with both Glastonbury and Avebury/Silbury through geometry, and also forms the crossing point of several prominent ley-lines – both astronomical and non-astronomical. The first astronomically significant ley-line to pass through Stonehenge was first identified by Sir Norman Lockyer, and later extended to 22 miles in length by K. Koop. This ley follows the path of the mid-summer sunrise on a bearing of 49� 15′. (2) Another significant ley-line to pass through Stonehenge was also identified by Lockyer, and can be shown to extend accurately for 18.5 miles. It skirts only the edge of the henge at the junction of the avenue, missing the centre (and the sarsen stones) altogether. This line runs on a bearing of 170� 45′, and appears to have no astronomical significance.

The alignments at Stonehenge therefore appear to offer a fusion of funerary, astronomical and geometric practices, simultaneously connecting three of the most significant locations in southern England. Glastonbury, Stonehenge and Avebury/Silbury, which all align to create a perfect right-angled triangle, accurate to within 1/1000th part. These alignments offer a indication that geometry might be involved in the orientation of some ley-lines. It is arguable that as many of the sites are aligned astronomically, and as geometry is a natural product of astronomy, the effect might be a product of ‘automatic’ or ‘accidental’ geometry within the layout of certain sites, but this does not explain geometry between sites which certainly involves surveying techniques, which in turn requires deliberate and applied mathematics (logarithms and trigonometry or their equivalent).

Sir Norman Lockyer (Astronomer-Royal), was the first ‘respectable’ person to recognize geometry in the ancient English landscape. He noticed the geometric alignment between Stonehenge, Grovely (Grove-ley) castle and Old Sarum (The site where the original Salisbury ‘cathedral was built). The three form an equilateral triangle with sides 6 miles long, with the Stonehenge-Old Sarum line continuing another 6 miles to the site of the present Salisbury Cathedral, and beyond.

This extremely significant finding shows both that the early megalithic builders were aware of both astronomy and geometry, and combined them deliberately into their constructions. At the same time as this reasonable astonishing revelation, we are able to see how many ley-markers may have been introduced along pre-existing alignments, and it is important to know the origin of all the markers on ley in order to accurately determine its origin and purpose.

The megalithic tradition in the British Isles can apparently be traced back to at least 3,000 B.C., if not earlier still. This tradition seems to have been based on a very sophisticated philosophy of sacred science such as was taught centuries later by the Pythagorean school. As Professor Alexander Thom observes in his book Megalithic Sites in Britain (1967): �It is remarkable that one thousand years before the earliest mathematicians of classical Greece, people in these islands not only had a practical knowledge of geometry and were capable of setting out elaborate geometrical designs but could also set out ellipses based on the Pythagorean triangles. (http://www.ancient-wisdom.com/leylines.htm)

Perhaps the most famous Ley in Britain is the ‘Michael and Mary’ line, which runs across England from Hopton in Norfolk to St. Michael’s Mount in Cornwall, and thence right around the globe. Aligned to Beltane and Lughnasadh / Lammas sunrise, this was first rediscovered by Jean Richer and John Michell and subsequently described in more detail by Hamish Miller and Paul Broadhurst in “The Sun and the Serpent” (1989).

Twin underground telluric currents, known as the Michael and Mary lines after the number of churches dedicated to either Mary or St. Michael to be found along them, weave around the central overground mid-line. This reveals the primal ‘Caduceus’ pattern that can be found within all true Leys: a triple-fold axis composed of masculine, feminine, and spirit currents, which may be experienced by the practising Geomancer as containing information in the thinking, feeling and spirit realms respectively.

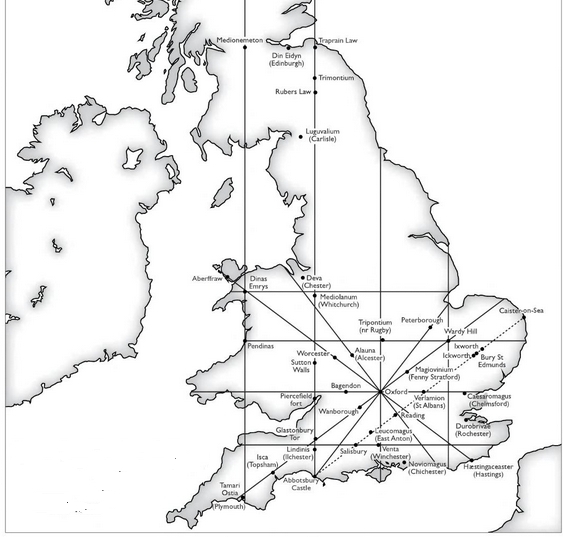

Ancient Paths by Graham Robb.

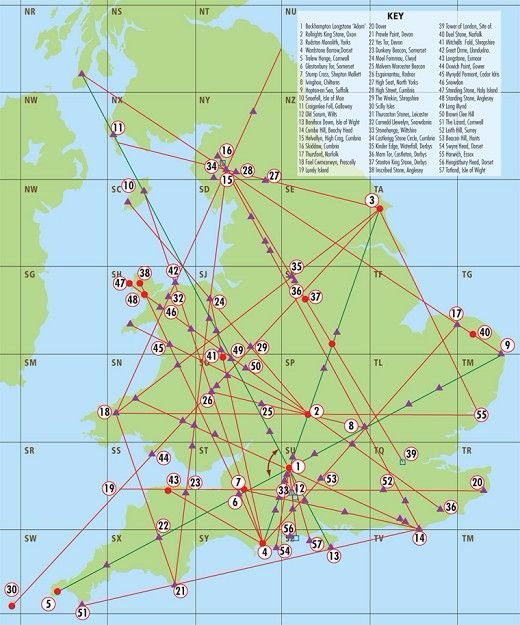

Major Ley lines of Britain.

Map of Ley lines in the UK.

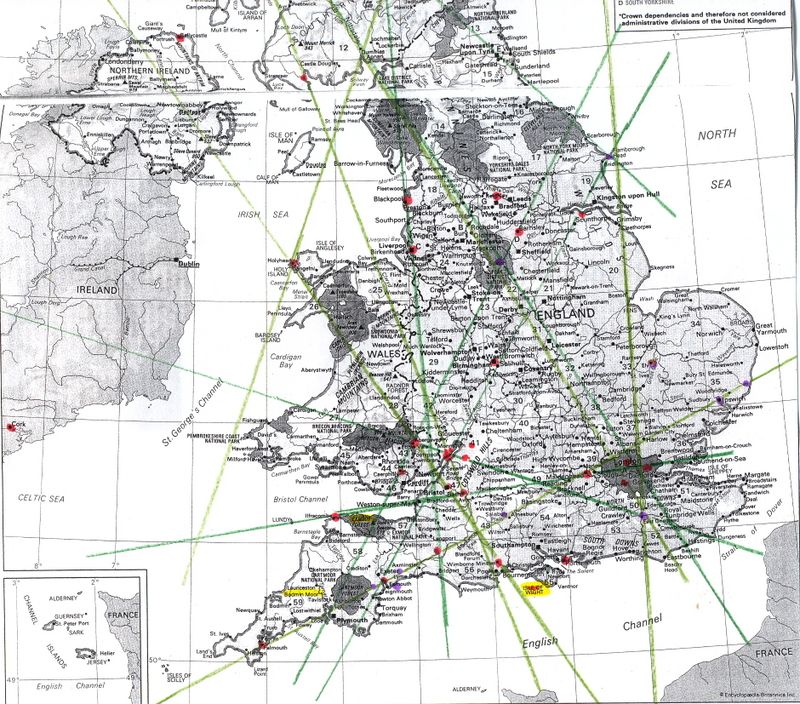

Belinus Ley line.

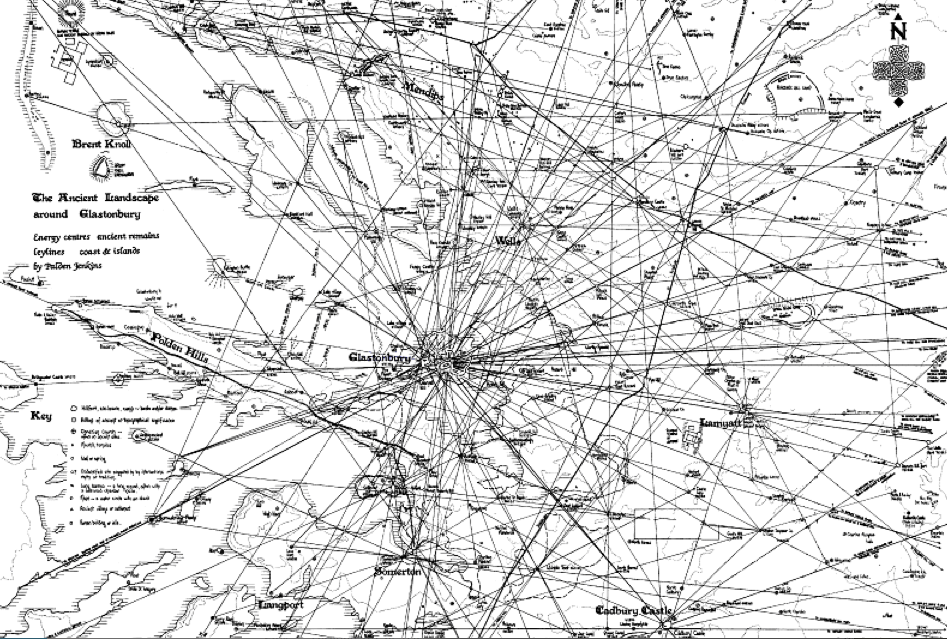

Map detailing the convergence of ley lines at Glastonbury, UK.

(Angmar Illustration)

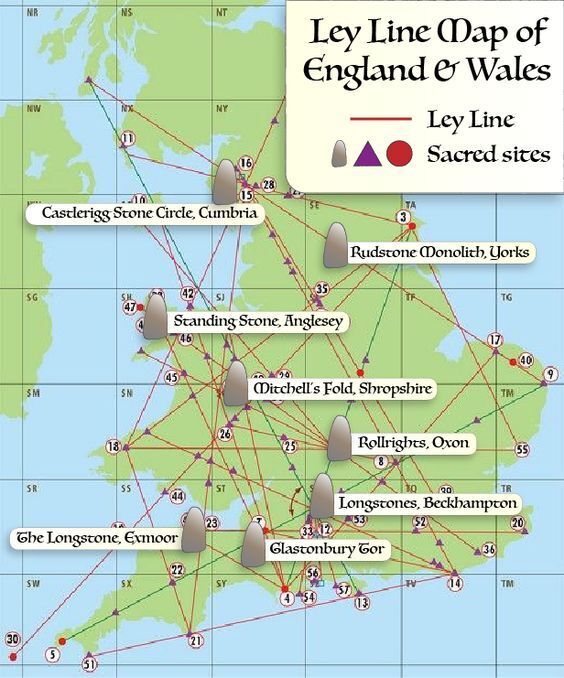

Ley lines map of England and Wales.

The question is, when were Ley Lines made? Exactly how old the original straight paths were is a matter of debate. We can read of ley-lines connecting offshore beneath the English channel (1), upon which basis, Behrand concluded that these particular leys must have been marked out between 7,000 BC and 6,000 BC.

We know that the European landscape was significantly redesigned using geometric principles in the middle ages by the Cathars, Knights Templar and the Holy church of Rome. We also know that a large number of the great Cathedrals Churches and Holy sites were built over earlier pre-existing pagan sites and constructions (Xewkija, Knowlton, Rudstone etc) The re-use of ancient sites can even be seen to extend back to pre-historic times such as the re-use of several large menhirs as capstones for passage-mounds in the region. It is this simple fact, combined with the observation that these same megalithic structures are invariably found to be the ley-points along which such lines are determined, that places the origin of ley-lines into the prehistoric past. (It by no means follows that all megalithic sites were placed on ley-lines).

It is not uncommon to find the terms ‘ley-lines’ and ‘roman roads’ in the same context, but it is important to draw a distinction between the two, as there is absolutely no pre-requisite for a ley-line to include roads, pathways, or any visible connection between ley-points of any kind whatsoever. It is the case however, that some ley-lines have been identified along which ancient paths or roads follow (or run alongside), and it is perhaps worth first considering the origin of these ancient tracks, and their connection with ley-lines.

In the first place, many of the long straight roads of Britain have been classified incorrectly as ‘Roman Roads’. A fact that can be proven through their existence in Ireland, as noted by J. Michell, who pointed out that ‘…these same roads exist in Ireland, a country which never suffered Roman occupation..‘, then also noted the fact that ‘…beneath the Roman surfaces of the Fosse Way, Ermine Street and Watling Street excavators have uncovered the paving stones of earlier roads, at least as well drained and levelled as those which succeeded them‘.

The same observation was made in other parts of Europe by the Romans themselves, who in their conquest of the Etruscans, noted standing stones set in linear patterns over the entire countryside of Tuscany. Romans also record discovering these ‘straight tracks’ in almost every country they subjugated: across Europe, North Africa, Crete, and the regions of ancient Babylon and Nineveh. Fairly conclusive then – the roads existed before the Romans. In fact, considering the scale of development in the Neolithic period approx 5,000 – 3,000 B.C. it is quite likely that they (or the first, or some at least), existed at that time too, if only to connect sites. )http://www.ancient-wisdom.com/leylines.htm)

Ley Lines in France

French investigators, have uncovered many line networks involving the main Cathedrals and places of interest…. perhaps the most astonishing of the French line networks is one centred on the tiny village of Alaise nestled in the foothills of the Jura mountains of eastern France.

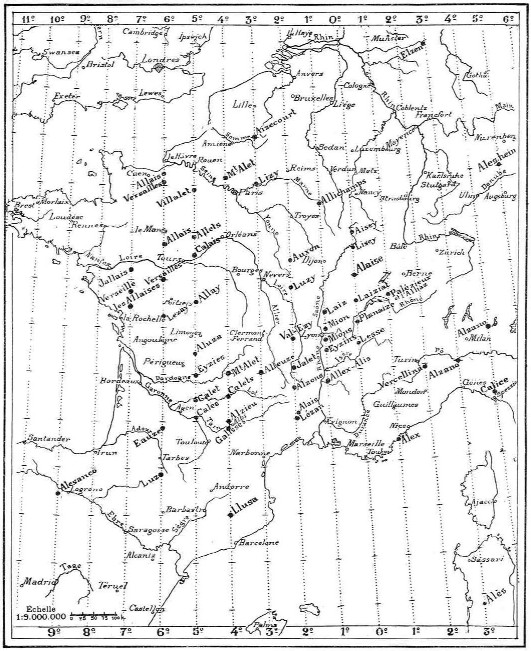

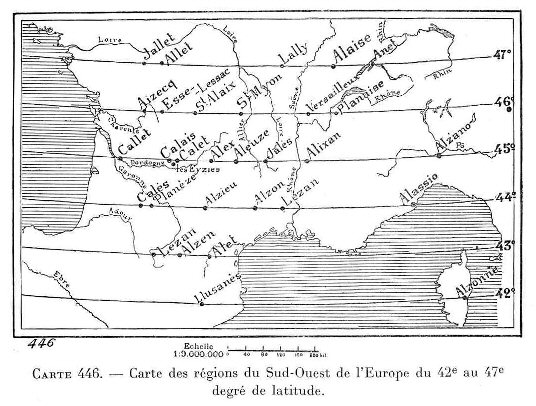

After devoted study by Xavier Guichard this tiny French village was found to be at the centre of a line system that radiated out to include dozens of sites, villages and towns of a similar name through many neighbouring countries over distances that spanned an area of many thousands of square miles. Yet perhaps the most astonishing thing of all was the realisation that this line system must have been initiated and planned thousands of years ago.

For many the geometric perfection of ley lines, the distances involved, in addition to the very remote period of their inception hints at a totally different view of the ancient world. In particular it shows the ancients were capable of a masterful degree of geodetic knowledge enabling them to accurately build sites in full alignment, even over hundreds of miles.

Xavier Guichard was a high-ranking police officer in Paris, Vice-President of the Prehistoric Society of France and one of the French investigators of ley lines theory. He detected many of them in France. One of the most famous of the French ley lines networks is situated in the small French village of Alaise in the vicinity of the Jura Mountains in the eastern part of France. Xavier Guichard found that the village of Alaise lies exactly at the center of a system of lines of longitude and latitude.

These lines, centred on Alaise, connect towns, villages and special places of a similar name in France and other countries. Guichard realized that the system must have been planned thousands of years ago. Guichard wrote a book about his discoveries. It was entitled “Eleusis-Alesi” but only 500 copies were printed in 1936. The book was a study on the origins of European civilization.

Lines, centred on Alaise village

Guichard’s conclusions: “…all places that were called Alesia (or a name closely related), had been given this name in prehistoric times. Not a single place had been given such a name in more recent times. He believed that this name was derived from an Indo-European root, meaning “a meeting point to where people travelled”. The majority of these sites could be found in France, where there were more than 400. But, as mentioned, the name occurred as far away as Greece and Egypt, and also in Poland and Spain. Guichard was unable to find such names in Britain, which suggests that these cities might go back to the time of the last Ice Age, when Britain was covered with thick sheets of ice. Guichard himself spoke of “prehistoric” centres…”

He discovered they had two characteristic features: they were on hills overlooking rivers and were built around a man-made well of salt or mineral water. He also believed that all the sites lay on lines radiating like the spokes of a wheel from the town of Alaise, about 40 kilometers to the south-east of Besançon, France. To him this suggested a carefully constructed design that would have required a mastery of both astronomy and planning. Indeed, he believed the system was not only prehistoric, but actually dated from the last Ice Age about 12,000 years ago. He based this conclusion on the observation that place names with these derivations ceased to occur in locations (latitudes) that had been covered by ice during the last Ice Age.

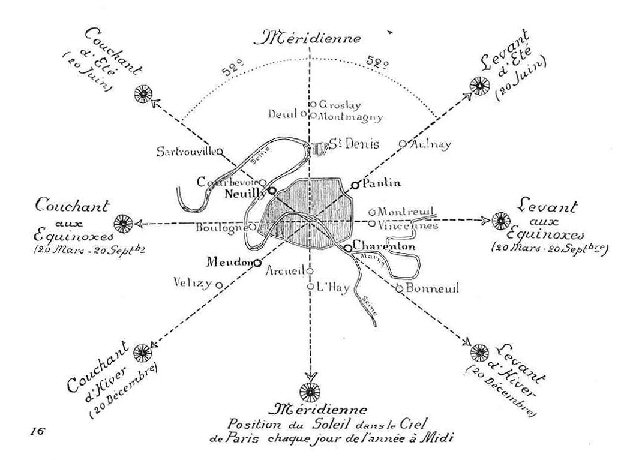

Guichard believed that 24 lines, equally spaced radiating lines, plus four lines based on the sunrise/sunset at the two equinoxes and the summer and winter solstices, touched every site. This was a total of28 lines, which could have a lunar connection. Intriguingly, a play of numbers, starting from 28 (which is two times 14, a number connected to dying gods such as Osiris and Jesus), gives numbers like 56, 64 and 72, all of them featuring prominently in sites such as Stonehenge, the megalithic civilization and other mythology. Of course, we can do a lot with numbers (which is, after all, what they were designed for in the first place), but it is interesting that certain key numbers keep coming back. Particularly, these numbers always have direct astronomical significance.”[1]

[1] Citation from Philip Coppens’ lecture. Internet: http://www.ufoarea.com/main_ley_lines.html.

It is possible to see that the French Meridian, which passes both the northerly and southerly points of France, also passes through Paris at the correct latitude for the summer and winter solstice sunrises and sunsets to occur at 52� off True North/South (A phenomena which is captured along the ‘Champs de Lysee’ (Tr. ‘Elysian Fields’), which is orientated along the path of the rising summer solstice sun and the setting winter solstice sun.

The Paris Meridian sits exactly 1� 09� east of the Greenwich Meridian (the same distance of separation as between the official eastern and western borders of ancient Egypt).

Alaisian Longitudinal lines.

Alaisian Latitudinal lines.

Many readers of this material, including Francis Hitching (Hitching, 1978), have seen a similarity between Guichard’s place-name derivations based on Alesia; and the English word ‘ley’, which Alfred Watkins (Watkins, 1925) had used to define the lines that went across the English countryside, joining up sacred places and key features in the landscape. Hitching concluded that fundamentally, both Alfred Watkins and Xavier Guichard were in agreement. They believed the ancient sites of early man did not happen by chance, but were placed carefully in a developing pattern. (Carol Ann, https://danceswithdragons.co.uk/)

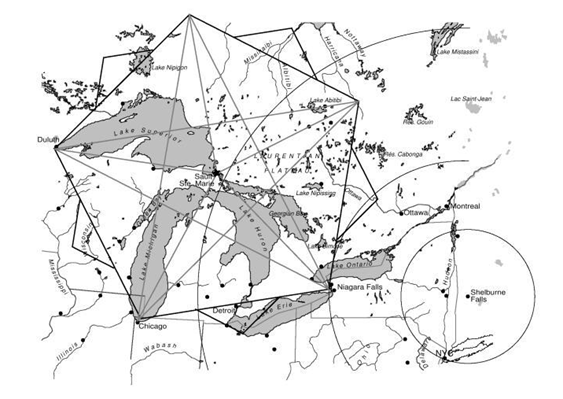

Ley lines are found around the world. This is a Map of Ley lines on the Great Lakes in North America.